Redalyc.Japanese Women's Role. Past and Present

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Japanese Film and Television Aaron Gerow

Yale University From the SelectedWorks of Aaron Gerow 2011 Japanese Film and Television Aaron Gerow Available at: https://works.bepress.com/aarongerow/42/ I J Routledge Handbook of Japanese Culture _andSociety "Few books offer such a broad and kaleidoscopic view of the complex and contested society that is contemporary Japan. Students and professionals alike may use this as a stand-alone reference text, or as an invitation to explore the increasingly diverse range of Japan-related titles offered by Routledge." Joy Hendry, Professor of Social Anthropology and Director of the Europe Japan Research Centre at Oxford Brookes University, UK Edited by Victoria Lyon Bestor and "This is the first reference work you should pick up if you want an introduction to contemporary Japanese society and culture. Eminent specialists skillfully pinpoint key developments Theodore C. Bestor, and explain the complex issues that have faced Japan and the Japanese since the end of World with Akiko Yamagata War II." Elise K. Tipton, Honorary Associate Professor of Japanese Studies in the School of Languages and Cultures at the University of Sydney, Australia I I~~?ia~:!!~~:up LONDON AND NEW YORK William H. Coaldrake I , I Further reading ,I Buntrock, Dana 2001 Japanese Architectureas a CollaborativeProcess: Opportunities in a Flexible Construction Culture. London: Spon Press. Coaldmke, William H. 1986-87 Manufactured Housing: the New Japanese Vernacular. Japan Architect 352-54, 357. ' 17 The Japan Foundation, and Architectural Institute of Japan 1997 ContemporaryJapanese Architecture, 1985-96. Tokyo: The Japan Foundation. JSCA 2003 Nihon kenchiku koz6 gijutsu kyokai (ed.), Nihon no kozo gijutsu o kaeta kenchikuhyakusen, Tokyo: Japanese film and television Shokokusha. -

THE Buddhist Thinker and Reformer Nichiren (1222–1282) Is Consid

J/Orient/03 03.10.10 10:55 AM ページ 94 A History of Women in Japanese Buddhism: Nichiren’s Perspectives on the Enlightenment of Women Toshie Kurihara OVERVIEW HE Buddhist thinker and reformer Nichiren (1222–1282) is consid- Tered among the most progressive of the founders of Kamakura Bud- dhism, in that he consistently championed the capacity of women to achieve salvation throughout his ecclesiastic writings.1 This paper will examine Nichiren’s perspectives on women, shaped through his inter- pretation of the 28-chapter Lotus Sutra of Gautama Shakyamuni in India, a version of the scripture translated by Buddhist scholar Kumara- jiva from Sanskrit to Chinese in 406. The paper’s focus is twofold: First, to review doctrinal issues concerning the spiritual potential of women to attain enlightenment and Nichiren’s treatises on these issues, which he posited contrary to the prevailing social and religious norms of medieval Japan. And second, to survey the practical solutions that Nichiren, given the social context of his time, offered to the personal challenges that his women followers confronted in everyday life. THE ATTAINMENT OF BUDDHAHOOD BY WOMEN Historical Relationship of Women and Japanese Buddhism During the Middle Ages, Buddhism in Japan underwent a significant transformation. The new Buddhism movement, predicated on simpler, less esoteric religious practices (igyo-do), gained widespread acceptance among the general populace. It also redefined the roles that women occupied in Buddhism. The relationship between established Buddhist schools and women was among the first to change. It is generally acknowledged that the first three individuals in Japan to renounce the world and devote their lives to Buddhist practice were women. -

Japanese Economic Growth During the Edo Period*

Japanese Economic Growth during the Edo Period* Toshiaki TAMAKI Abstract During the Edo period, Japanese production of silver declined drastically. Japan could not export silver in order to import cotton, sugar, raw silk and tea from China. Japan was forced to carry out import-substitution. Because Japan adopted seclusion policy and did not produce big ships, it used small ships for coastal trade, which contributed to the growth of national economy. Japanese economic growth during the Edo period was indeed Smithian, but it formed the base of economic development in Meiji period. Key words: Kaimin, maritime, silver economic growth, Sakoku 1.Introduction Owing to the strong influence of Marxism, and Japan’s defeat in World War II, Japanese historians dismissed the Edo period (1603–1867) as a stagnating period. Japan, during this period, was regarded as a country that lagged behind Europe because of its underdeveloped social and economic systems. It had been closed to the outside world for over two hundred years, as a result of its Sakoku (seclusion) policy, and could not, therefore, progress as rapidly as Europe and the United States. This image of Japan during the Edo period began to change in the 1980s, and this period is now viewed as an age of economic growth, even if Japan’s growth rates were not as rapid as those of Europe. Economic growth during the Edo period is now even considered to be the foundation for the economic growth that occurred after the Meiji period. In this paper, I will develop three arguments that demonstrate the veracity of the above viewpoint. -

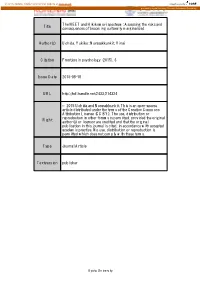

Title the NEET and Hikikomori Spectrum

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Kyoto University Research Information Repository The NEET and Hikikomori spectrum: Assessing the risks and Title consequences of becoming culturally marginalized. Author(s) Uchida, Yukiko; Norasakkunkit, Vinai Citation Frontiers in psychology (2015), 6 Issue Date 2015-08-18 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/214324 © 2015 Uchida and Norasakkunkit. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original Right author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms. Type Journal Article Textversion publisher Kyoto University ORIGINAL RESEARCH published: 18 August 2015 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01117 The NEET and Hikikomori spectrum: Assessing the risks and consequences of becoming culturally marginalized Yukiko Uchida 1* and Vinai Norasakkunkit 2 1 Kokoro Research Center, Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan, 2 Department of Psychology, Gonzaga University, Spokane, WA, USA An increasing number of young people are becoming socially and economically marginalized in Japan under economic stagnation and pressures to be more globally competitive in a post-industrial economy. The phenomena of NEET/Hikikomori (occupational/social withdrawal) have attracted global attention in recent years. Though the behavioral symptoms of NEET and Hikikomori can be differentiated, some commonalities in psychological features can be found. Specifically, we believe that both NEET and Hikikomori show psychological tendencies that deviate from those Edited by: Tuukka Hannu Ilmari Toivonen, governed by mainstream cultural attitudes, values, and behaviors, with the difference University of London, UK between NEET and Hikikomori being largely a matter of degree. -

Health Employment and Economic Growth

Health Employment An Evidence Base Health Employment and Economic Growth Powerful demographic and economic forces are shaping health The 17 chapters and Economic Growth workforce needs and demands worldwide. in this book, are grouped into Effectively addressing current and future health workforce four parts: An Evidence Base needs and demands stands as one of our foremost challenges. It also represents an opportunity to secure a future that is • Health workforce healthy, peaceful, and prosperous. dynamics The contents of this book give direction and detail to a richer • Economic value Edited by and more holistic understanding of the health workforce and investment James Buchan through the presentation of new evidence and solutions- focused analysis. It sets out, under one cover, a series of • Education and Ibadat S. Dhillon research studies and papers that were commissioned to production provide evidence for the High-Level Commission on Health James Campbell Employment and Economic Growth. • Addressing inefficiencies ‘’An essential read that rightfully places investments in health workforce at the heart of the SDG Agenda.” — Richard Horton, Editor-in-Chief The Lancet “A resource of fundamental importance. Evidences the socio-economic benefits that follow from appropriately recognizing, rewarding, and supporting women’s Campbell Dhillon Buchan work in health.” — H.R.H. Princess Muna al-Hussein, Princess of Jordan Health Employment and Economic Growth An Evidence Base Edited by James Buchan Ibadat S. Dhillon James Campbell i Health Employment and Economic Growth: An Evidence Base ISBN 978-92-4-151240-4 © World Health Organization 2017 Some rights reserved. This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- ShareAlike 3.0 IGO licence (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/igo). -

The Otaku Phenomenon : Pop Culture, Fandom, and Religiosity in Contemporary Japan

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 12-2017 The otaku phenomenon : pop culture, fandom, and religiosity in contemporary Japan. Kendra Nicole Sheehan University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, Japanese Studies Commons, and the Other Religion Commons Recommended Citation Sheehan, Kendra Nicole, "The otaku phenomenon : pop culture, fandom, and religiosity in contemporary Japan." (2017). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2850. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/2850 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE OTAKU PHENOMENON: POP CULTURE, FANDOM, AND RELIGIOSITY IN CONTEMPORARY JAPAN By Kendra Nicole Sheehan B.A., University of Louisville, 2010 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Humanities Department of Humanities University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky December 2017 Copyright 2017 by Kendra Nicole Sheehan All rights reserved THE OTAKU PHENOMENON: POP CULTURE, FANDOM, AND RELIGIOSITY IN CONTEMPORARY JAPAN By Kendra Nicole Sheehan B.A., University of Louisville, 2010 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Approved on November 17, 2017 by the following Dissertation Committee: __________________________________ Dr. -

Westernization in Japan: America’S Arrival

International Journal of Management and Applied Science, ISSN: 2394-7926 Volume-3, Issue-8, Aug.-2017 http://iraj.in WESTERNIZATION IN JAPAN: AMERICA’S ARRIVAL TANRIO SOPHIA VIRGINIA English Literature Department BINUS UNIVERSITY Indonesia E-mail: [email protected] Abstract- As America arrived with westernization during late Edo period also known as Bakumatsu period, Japan unwelcomed it. The arrival of America in Japan had initiated the ‘wind of change’ to new era towards Japan culture albeit its contribution to Japan proffers other values at all cost. The study aims to emphasize the importance of history in globalization era by learning Japan's process in accepting western culture. By learning historical occurrences, cultural conflicts can be avoided or minimized in global setting. The importance of awareness has accentuated an understanding of forbearance in cultural diversity perspectives and the significance of diplomatic relation for peace. Systematic literature review is applied as the method to analyze the advent of America, forming of treaty, Sakoku Policy, Diplomatic relationship, and Jesuit- Franciscans conflict. The treaty formed between Japan and America served as the bridge for Japan to enter westernization. Keywords- Westernization, Japan, America, Sakoku Policy, Jesuit-Franciscans Conflict, Treaty, Culture, Edo Period. I. INTRODUCTION Analysing from the advent of America leads to Japan’s Sakoku Policy which took roots from a Bakumatsu period or also known as Edo period, dispute caused by westerners when Japan was an specifically in the year of 1854 in Capital of Kyoto, open country. This paper provides educational values Japan, was when the conflict between Pro-Shogunate from historical occurrences. -

The Significance of Anime As a Novel Animation Form, Referencing Selected Works by Hayao Miyazaki, Satoshi Kon and Mamoru Oshii

The significance of anime as a novel animation form, referencing selected works by Hayao Miyazaki, Satoshi Kon and Mamoru Oshii Ywain Tomos submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Aberystwyth University Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies, September 2013 DECLARATION This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. STATEMENT 1 This dissertation is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged explicit references. A bibliography is appended. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. STATEMENT 2 I hereby give consent for my dissertation, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. 2 Acknowledgements I would to take this opportunity to sincerely thank my supervisors, Elin Haf Gruffydd Jones and Dr Dafydd Sills-Jones for all their help and support during this research study. Thanks are also due to my colleagues in the Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies, Aberystwyth University for their friendship during my time at Aberystwyth. I would also like to thank Prof Josephine Berndt and Dr Sheuo Gan, Kyoto Seiko University, Kyoto for their valuable insights during my visit in 2011. In addition, I would like to express my thanks to the Coleg Cenedlaethol for the scholarship and the opportunity to develop research skills in the Welsh language. Finally I would like to thank my wife Tomoko for her support, patience and tolerance over the last four years – diolch o’r galon Tomoko, ありがとう 智子. -

Construction and Verification of the Scale Detection Method for Traditional Japanese Music – a Method Based on Pitch Sequence of Musical Scales –

International Journal of Affective Engineering Vol.12 No.2 pp.309-315 (2013) Special Issue on KEER 2012 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Construction and Verification of the Scale Detection Method for Traditional Japanese Music – A Method Based on Pitch Sequence of Musical Scales – Akihiro KAWASE Department of Corpus Studies, National Institute for Japanese Language and Linguistics, 10-2 Midori-cho, Tachikawa City, Tokyo 190-8561, Japan Abstract: In this study, we propose a method for automatically detecting musical scales from Japanese musical pieces. A scale is a series of musical notes in ascending or descending order, which is an important element for describing the tonal system (Tonesystem) and capturing the characteristics of the music. The study of scale theory has a long history. Many scale theories for Japanese music have been designed up until this point. Out of these, we chose to formulate a scale detection method based on Seiichi Tokawa’s scale theories for traditional Japanese music, because Tokawa’s scale theories provide a versatile system that covers various conventional scale theories. Since Tokawa did not describe any of his scale detection procedures in detail, we started by analyzing his theories and understanding their characteristics. Based on the findings, we constructed the scale detection method and implemented it in the Java Runtime Environment. Specifically, we sampled 1,794 works from the Nihon Min-yo Taikan (Anthology of Japanese Folk Songs, 1944-1993), and performed the method. We compared the detection results with traditional research results in order to verify the detection method. If the various scales of Japanese music can be automatically detected, it will facilitate the work of specifying scales, which promotes the humanities analysis of Japanese music. -

Report of the Ship for World Youth Leaders (SWY) for FY2019

Chapter 3 Evaluations Evaluation by the Administrator )858<$,FKLUR 'LUHFWRU2IILFHIRU,QWHUQDWLRQDO<RXWK([FKDQJH&DELQHW2IILFH This year, Ship for World Youth Program (SWY) held everywhere in the ship on every night. started on January 11th, 2020, when all Participating Youths The Port of Call Activity in Ensenada, from January (PYs) gathered in Tokyo. After boarding on Nippon Maru 30th to February 1st, became very fruitful due to the and departing from Port of Yokohama on January 16th, the devoted preparation done by the alumni association. When PYs completed 35 days of round voyage on Pacific Ocean we visited the wall on the border between Mexico and as well as Port of Call Activities in United Mexican States. US during the activity, some PYs gave way to tears. Also The completion ceremony and farewell party were held on for other PYs, it became meaningful opportunity to think February 20th, and the program finished on February 24th, about international affairs. when Overseas PYs ended their Regional Program and In this year’s voyage, we had to change the schedule returned to their home countries. I would like to express unexpectedly, as prolongation of arrival to port of Tokyo my deepest gratitude to all the people who supported the for one day by the influence of climate condition. But program and led the program to be completed successfully even in such occasion, PYs received them in very positive and safely. attitude and used their time very effectively. For PYs, it was totally their first experience that they By the way, through the whole voyage, what I was very stayed with others from all over the world who have impressed by are the PYs’ kind hearts for others. -

I TEAM JAPAN: THEMES of 'JAPANESENESS' in MASS MEDIA

i TEAM JAPAN: THEMES OF ‘JAPANESENESS’ IN MASS MEDIA SPORTS NARRATIVES A Dissertation submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Michael Plugh July 2015 Examining Committee Members: Fabienne Darling-Wolf, Advisory Chair, Media and Communication Doctoral Program Nancy Morris, Media and Communication Doctoral Program John Campbell, Media and Communication Doctoral Program Lance Strate, External Member, Fordham University ii © Copyright 2015 by MichaelPlugh All Rights Reserved iii Abstract This dissertation concerns the reproduction and negotiation of Japanese national identity at the intersection between sports, media, and globalization. The research includes the analysis of newspaper coverage of the most significant sporting events in recent Japanese history, including the 2014 Koshien National High School Baseball Championships, the awarding of the People’s Honor Award, the 2011 FIFA Women’s World Cup, wrestler Hakuho’s record breaking victories in the sumo ring, and the bidding process for the 2020 Olympic Games. 2054 Japanese language articles were examined by thematic analysis in order to identify the extent to which established themes of “Japaneseness” were reproduced or renegotiated in the coverage. The research contributes to a broader understanding of national identity negotiation by illustrating the manner in which established symbolic boundaries are reproduced in service of the nation, particularly via mass media. Furthermore, the manner in which change is negotiated through processes of assimilation and rejection was considered through the lens of hybridity theory. iv To my wife, Ari, and my children, Hiroto and Mia. Your love sustained me throughout this process. -

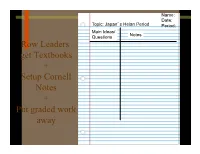

7.5 Heian Notes

Name: Date: Topic: Japan’s Heian Period Period: Main Ideas/ Questions Notes Row Leaders get Textbooks + Setup Cornell Notes + Put graded work away A New Capital • In 794, the Emperor Kammu built a new capital city for Japan, called Heian-Kyo. • Today, it is called Kyoto. • The Heian Period is called Japan’s “Golden Age” Essential Question: What does “Golden Age” mean? Inside the city • Wealthy families lived in mansions surrounded by gardens. A Powerful Family • The Fujiwara family controlled Japan for over 300 years. • They had more power than the emperor and made important decisions for Japan. Beauty and Fashion • Beauty was important in Heian society. • Men and women blackened their teeth. • Women plucked their eyebrows and painted them higher on their foreheads. Beauty and Fashion • Heian women wore as many as 12 silk robes at a time. • Long hair was also considered beautiful. Entertainment • The aristocracy had time for diversions such as go (a board game), kemari (keep the ball in play) and bugaku theater. Art • Yamato-e was a style of Japanese art that reflected nature from the Japanese religion of Shinto. Writing and Literature • The Tale of Genji was written by Murasaki Shikibu, a woman, and is considered the world’s first novel. Japanese Origami Book Blah blah blah blah. Blah blah blah blah. Blah blah blah blah. Blah blah blah blah. Blah blah blah blah. Blah blah blah blah. .