THE SPECIAL STATUS of the LADIN VALLEYS Günther

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Un Bando, Tante Storie Umane La Camera Di Commercio Ci Ha Creduto E I Finanziamenti Sono Arrivati Ai Negozi Di Vicinato Vera Colonna Portante Durante Il Lockdown

COMUNICATO STAMPA 1 milione e 430mila euro: un bando, tante storie umane La Camera di Commercio ci ha creduto e i finanziamenti sono arrivati ai negozi di vicinato vera colonna portante durante il lockdown Belluno, 15 Gennaio 2021. Voglio condividere con voi l’orgoglio per averci creduto anche in un momento in cui sembrava non ci fosse nulla a cui credere se non che c’era una pandemia mai vista prima – dice con tono fermo il Presidente Pozza -. Eravamo da subito convinti che i finanziamenti dovessero andare a chi ne aveva effettivamente bisogno e che sarebbe stato un garanzia importante per supportare le difficoltà sociali causate dal lockdown da Coronavirus. Non si tratta di acquisto di presidi medici, ma di vera e propria vita quotidiana, che ha bisogno di approvvigionamenti e di consegne a domicilio dando così conforto, supporto logistico e aiutato chi in alta montagna vive e lavora o chi doveva rimanere in isolamento. C’è chi ha voluto ampliare attività esistenti rendendoli polifunzionali, chi ha creato nuove attività per rispondere a nuovi bisogni, chi ha voluto restaurare i muri, le facciate per rendere più accoglienti i propri negozi. Ma dietro alle pratiche ci sono persone e storie, come chi, in difficoltà per il COVID, ha fatto telefonare alla Camera di commercio, per assicurarsi che le pratiche del bando, presentate per i propri clienti, fossero andate a buon fine. Ci sono due graduatorie distinte, una relativa agli interventi localizzati nei comuni confinanti e contigui con il Trentino Alto Adige, l’altra relativa agli interventi localizzati nei rimanenti comuni provinciali. -

2 Stadionblattl Din A4 Ausgabe 2. 2015-2016

Ausgabe 2 Seite 1 Saison 2015/2016 20.09.2015 Hallo und Grüß Gott!! Wir Begrüßen euch heute hier in der Collarena zum zweiten Heimspiel der Saison 2015/2016. Nach den Niederlagen zu Saisonbeginn gegen St. Lorenzen (1:4) und beim ersten Heimspiel gegen Ter- enten (0:2), reiste man voller Tatendrang nach Olang. Der erste Dreier sollte eingefahren werden. Doch schon in der Anfangsphase wurde man eiskalt erwischt. In der 1. Spielminute schlug das Leder im Kasten von Renè Aichner ein und man musste schon wieder einen 0:1 Rückstand hinterher laufen. Die Chancen den Ausgleich zu erzielen waren da, doch ist die Torausbeute zur Zeit sehr dünn. So kam es wie es kommen musste, machst du sie nicht, macht es der Andere. So stehen wir in der Tabelle mit 0 Punkten und einem Torverhältnis von 1:8 Toren an der vorletzten Stelle. Unser Gegner heute Rina Welschellen hat schon 6 Punkte auf dem Konto und belegt derzeit den 5. Tabellenplatz. Trotzdem auf geht’s Jungs Kopf hoch die Saison ist noch jung, das packen wir!!!! Ein Tal!!! Ein Verein!!! Eine Mannschaft!!! Heute der 4. Spieltag In dieser Ausgabe Auswahl Ridnauntal-Vintl- Aktuelle Tabelle S. 1 Franzenfeste-Mareo St. Vigil Gegner Heute S. 2 Gais-Taisten/Welsberg US Rina Welschellen Rasen/Antholz-St. Lorenzen Der Spielkalender S. 3 Teis/Villnöss-Rina Welschellen 2. Amateurliga Terenten-Olang 2. Spieltag 2.Amateurliga S. 4 gegen Terenten 3. Spieltag 2. Amateurliga S. 5 Platz Team Sp. G U N Tore +/- Pkt. gegen Olang 1 St. Lorenzen 3 3 0 0 10:2 +8 9 Das Team 2015/2016 S. -

Routeboekje 2012.Pdf

Plaats, wegnummer, afstand (in km) en hoogte (in m) plaats weg nr. km m plaats weg nr. km m Etappe 1: 94 km - ca. 2250 hm Merano 0 314 Tires P65 57 1020 Marlengo S238 3 282 > Lavina Bianca P65 60 1080 Cermes S238 5 282 Passo Nigra P65 67 1688 Lana S238 8 313 Top P65 71 1788 Narano P10 14 674 > SS241 S241 75 1706 Tesimo P10 15 634 Passo di Costalunga S241 78 1745 Prissiano P10 17 602 Vallonga S241 82 1489 Nàlles P54 20 304 Vigo di Fassa P238 84 1395 Andriano P11 24 280 Pozza di Fassa P238 86 1307 > Terlano S38 25 248 Pera P238 87 1316 Bolzano 34 273 Mazzin P238 90 1370 Cornedo S12 38 281 Campestrin P238 91 1377 Prato all' Isarco / Blumau P24 43 327 Fontanazzo P238 92 1389 > SP65 P65 45 470 Campitello di Fassa P238 94 1424 Aica di Sopra P65 51 912 Etappe 2: 100 km - ca. 2900 hm Campitello di Fassa P238 0 1424 Passo di Valparola P24 47 2192 Arles P238 2 1447 Armentarola P24 55 1639 Canazei S48 3 1450 San Cassiano P24 58 1526 > Passo di Sella S48 9 1826 Costadedoi P24 59 1502 Passo Pordoi S48 15 2239 Cianins P24 60 1405 Pallua S48 23 1706 La Villa S244 61 1420 Arabba S48 24 1595 Funtanacia S244 62 1441 Alfauro S48 26 1516 Corvara in Badia S243 65 1524 Renaz S48 27 1484 Colfosco S243 68 1640 Liviné / Brenta S48 31 1459 Passo di Gardena S243 75 2121 Pieve di Livinallongo S48 32 1460 > Plan de Gralba S242 81 1878 > Rocca Pietore S48 34 1440 Passo di Sella S242 86 2244 Andraz S48 35 1436 > Passo Pordoi S48 91 1826 Cernadoi S48 36 1524 Canazei P238 97 1450 Plan di Falzarego S48 43 1936 Arles P238 99 1447 > SR 48 (p di Falzarego) P24 45 2103 Campitello di Fassa P238 100 1424 Etappe 3: 103 km - ca. -

Cortina-Calalzo. Long Way of the Dolomites. Difficulty Level

First leg Distance: 48 km 4.1 Cortina-Calalzo. Long Way of the Dolomites. Difficulty level: “Long Way of Dolomiti” on the old and passes by exclusive hotels and communities in the Cadore area) and railway tracks that were built in the stately residences. After leaving the another unique museum featuring Dolomites during World War I and famous resort valley behind, the eyeglasses. Once you’ve reached closed down in 1964. Leftover from bike trail borders the Boite River to Calalzo di Cadore, you can take that period are the original stations (3), the south until reaching San Vito the train to Belluno - this section tunnels, and bridges suspended over di Cadore (4), where the towering doesn’t have a protected bike lane spectacular, plummeting gorges. massif of monte Antelao challenges and in some places the secondary The downhill slopes included on the unmistakable silhouette of monte roads don’t guarantee an adequate this trip are consistent and easily Pelmo (2). In Borca di Cadore, the level of safety. managed; the ground is paved in trail moves away from the Boite, which wanders off deep into the 1 valley. The new cycle bridges and The Veneto encompasses a old tunnels allow you to safely pedal vast variety of landscapes and your way through the picturesque ecosystems. On this itinerary, you towns of Vodo, Venas, Valle, and Tai. will ride through woods filled In Pieve di Cadore, you should leave with conifers native to the Nordic enough time to stop at a few places countries as well as Holm oak of artistic interest, in addition to the woods that are present throughout family home of Tiziano Vecellio, the Mediterranean. -

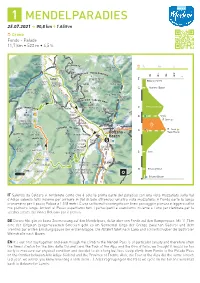

Mendelparadies

1 MENDELPARADIES 25.07.2021 90,8 km 1.659 m Crono Fondo - Palade 11,7 km • 523 m • 4,5 % h m s 1500 1000 2000 500 m km Bolzano | Bozen 9,5 Appiano | Eppan 26 Mendola | Mendel 34 Fondo 35,5 Start 47 48 Finish Passo Palade 66 Lana 81 Terlano | Terlan Bolzano | Bozen IT Salendo da Caldaro vi renderete conto che è solo la prima parte del paradiso con una vista mozzafiato sulla Val d’Adige salendo tutti insieme per arrivare in Val di Sole offrendoci un’altra vista mozzafiato. A Fondo parte la lunga cronometro per il passo Palace a 1.518 metri. È una salita molto variegata con brevi passaggi in pianura e leggera salita ma piuttosto lunga. Arrivati al Passo aspettiamo tutti i partecipanti e scendiamo insieme a Lana per rientrare per la vecchia strada del Vino a Bolzano per il pranzo. DE Dieses Mal gibt es keine Zeitmessung auf den Mendelpass, dafür aber von Fondo auf den Gampenpass. Mit 11,7 km eine der längsten zeitgemessenen Strecken geht es im Sonnental längs der Grenze zwischen Südtirol und dem Trentino zur ersten Erholungspause der ersten Etappe. Die Abfahrt führt nach Lana und schließlich über die Südtiroler Weinstraße nach Bozen. EN It’s our first day together and even though the climb to the Mendel Pass is of particular beauty and therefore often the timed stretch for the Giro delle Dolomiti and the Tour of the Alps and the Giro d’Italia, we thought it would be too early to measure our physical condition and decided to do a long but less steep climb from Fondo to the Palade Pass on the frontier between Alto Adige Südtirol and the Province of Trento. -

Dell'aquila, Vittorio/Iannàccaro, Gabriele: Survey Ladins. Usi

372 Ladinia XXXII (2008) / REZENJIUNS Joachim Born DELL’AQUILA, Vittorio/IANNÀCCARO, Gabriele: Survey Ladins. Usi linguistici nelle valli ladine, Trento/Vich, Regione Autonoma Trentino-Alto Adige/Isti- tut Cultural Ladin “Majon di Fascegn”, 2006, 422 pp. Die beiden Verfasser legen einen ausgesprochen schön illustrierten und farben- prächtigen Band zum Sprachgebrauch in den ladinischen Dolomitentälern vor. Die vielen Abbildungen und Karten machen das Werk sehr anschaulich, aber – aufgepasst Zug- und Flugreisende! – auch ziemlich schwer (1.409g). 1.450 Männern und 1.538 Frauen in den fünf ladinischen Tälern Gröden, Gader- tal, Fassa, Buchenstein und Ampezzo wurden in einem Questionnaire 92 Fragen vorgelegt. Damit wurden rund 10% der gesamten Wohnbevölkerung erfasst, die nach den gängigen Faktoren Wohnort, Alter und Geschlecht quotiert wurde, und so ist eine Repräsentativität wohl allemal gewährleistet. Das Schicksal von em- pirischen quantitativen Befragungen ist, dass sie mit Tausenden Befragten in der Regel die gleichen Ergebnisse liefern wie mit 150, dass sie schlimmstenfalls nur das dokumentieren, was man ohnehin schon aus eigener Beobachtung wusste. Dennoch sind sie natürlich nötig, um Datenmaterial für notwendige, in diesem Falle sprachpolitische Maßnahmen zu liefern. Der Fragebogen konnte auf ladin dolomitan (mehrheitlich nur in San Martin de Tor, La Val und Badia gewählt), Deutsch (in Gröden außer Sëlva sowie in Mareo) oder Italienisch (sämtliche Gemeinden in den Provinzen Belluno und Trient sowie Corva- ra und Sëlva) ausgefüllt werden (194). Die Verfasser verwenden Analysemethoden, die zum einen eher Interpretationsvorschlägen folgen, die “particolarmente rigorose (e forse dunque anche rigide) dal punto di vista matematico” sind, zum anderen eher “procedimenti più tipicamente in uso nella sociolinguistica interpretativa” verwen- den (6). -

The Cheeses Dolomites

THE CHEESES UNIONE EUROPEA REGIONE DEL VENETO OF THE BELLUNO DOLOMITES Project co-financed by the European Union, through the European Regional Development fund. Community Initiative INTERREG III A Italy-Austria. Project “The Belluno Cheese Route – Sights and Tastes to Delight the Visitor.” Code VEN 222065. HOW THEY ARE CREATED AND HOW THEY SHOULD BE ENJOYED HOW THEY ARE CREATED AND HOW THEY SHOULD BE ENJOYED HOW THEY ARE CREATED BELLUNO DOLOMITES OF THE CHEESES THE FREE COPY THE CHEESES OF THE BELLUNO DOLOMITES HOW THEY ARE CREATED AND HOW THEY SHOULD BE ENJOYED his booklet has been published as part of the regionally-managed project “THE BELLUNO CHEESE ROUTE: SIGHTS AND TASTES TO TDELIGHT THE VISITOR”, carried out by the Province of Belluno and the Chamber of Commerce of Belluno (with the collaboration of the Veneto Region Milk Producers’ Association) and financed under the EU project Interreg IIIA Italy-Austria. As is the case for all cross-border projects, the activities have been agreed upon and developed in partnership with the Austrian associations “Tourismusverband Lienzer Dolomiten” (Lienz- Osttirol region), “Tourismusverband Hochpustertal” (Sillian) and “Verein zur Förderung des Stadtmarktes Lienz”, and with the Bolzano partner “Centro Culturale Grand Hotel Dobbiaco”. The project is an excellent opportunity to promote typical mountain produce, in particular cheeses, in order to create a close link with the promotion of the local area, culture and tourism. There is a clear connection between, one the one hand, the tourist, hotel and catering trades and on the other, the safeguarding and promotion of typical quality produce which, in particular in mountain areas, is one of the main channels of communication with the visitor, insofar as it is representative of the identity of the people who live and work in the mountains. -

Terrazzamenti E Muri a Secco

TERRAZZAMENTI E MURI A SECCO FUNZIONI E CENNI STORICI dall’origine o dal grado di finitura del materiale litoide, l’elemento accomunante I muri a secco e i terrazzamenti è costituito dall’assenza, o quasi, di costituiscono un elemento visivo di legante, motivo per cui la coesione tra le particolare rilevanza nel paesaggio parti costituenti dipende unicamente dalla rurale e testimoniano la tenace opera forza di gravità e dal grado di aderenza tra dell’uomo per sottrarre terreno praticabile le componenti. e coltivabile alla montagna. L’economia degli insediamenti storici è contraddistinta da un rigoroso rispetto nei confronti del territorio, in quanto fonte primaria di sostentamento, ovvero strumento che consente la pratica dell’agricoltura, l’allevamento del bestiame, la produzione di fieno, di legna da ardere e di legname da costruzione. In questo sistema gli orti e i campi, per la loro prossimità agli abitati, sono a servizio esclusivo delle singole residenze, mentre i prati, i pascoli e i boschi sono Longarone, frazione Soffranco utilizzati dalla collettività. Le condizioni morfologiche di un ambiente contraddistinto da versanti acclivi e connotato da salti di quota rilevanti impongono di “incidere” il territorio per modellare le pendenze, così da ricavare ambiti coltivabili o tracciati percorribili per raggiungere i boschi e gli alpeggi. I muri a secco divengono lo strumento principe per contenere il suolo, sia sottoforma di sostegno a terrazzamenti, sia quale limite, a valle e a monte, di percorsi che tagliano versanti ripidi e instabili. Tutto l’ambito oggetto di studio è Cortina d’Ampezzo, località Zuel di Sopra connotato dalla presenza di tali manufatti, che costituiscono un elemento integrante In passato i campi producevano del paesaggio e partecipano all’equilibrio modeste quantità di cereali, fagioli e dei luoghi anche in virtù del materiale con patate. -

Strada Dei Formaggi Delle Dolomiti Itinerari Lungo La Strada Dei Formaggi Delle Dolomiti DOLOMITE CHEESE ROUTE Dolomite Cheese Route Itineraries

Strada dei Formaggi delle dolomiti Itinerari lungo la Strada dei Formaggi delle Dolomiti DOLOMITE CHEESE ROUTE Dolomite Cheese Route itineraries Dalla Val di Fassa alle Pale di San Martino Valli di Fiemme, Fassa, Primiero A From Fassa Valley to Pale of San Martino La differenza tra mangiare e assaporare, I Magnifici Prodotti della Val di Fiemme dormire e riposare, acquistare e scoprire B Magnificient products of Fiemme The difference between eating and tasting, Primiero, filo diretto tra passato e futuro C sleeping and resting, buying and discovering Primiero between past and present www.stradadeiformaggi.it Per scoprire i dettagli di questi itinerari, A 48 50 63 richiedi la brochure della Strada dei Formaggi delle Dolomiti presso gli uffici ApT 48 For further details on these tours, ask for the Dolomite Cheese Route brochure at the Tourist Board information offices 32 3 I nostri prodotti BellUno Our products 92 93 65 FORMAGGI 49 66 CHEESE 91 Puzzone di Moena, Caprino di Cavalese, Cuor di Fassa, Tosèla e Primiero, Dolomiti, Fontal di Bolzano Cavalese, Trentingrana, Botìro di Primiero di Malga A e i tanti Nostrani, uno diverso dall’altro Puzzone di Moena, Caprino di Cavalese, Cuor 94 di Fassa, Tosèla di Primiero, Dolomiti, Fontal di 64 Cavalese, Trentingrana, Botìro di Primiero di Malga and the various Nostrani (local cheeses), each one 61 62 different to the next 33 MIELE A HONEY Miele di millefiori d’alta montagna, miele di rododendro e melata di abete Bolzano A Mountain wild-flower honey, rhododendron honey A and fir honeydew TrenTo -

Valori Agricoli Medi Della Provincia Annualità 2014

Ufficio del territorio di TRENTO Data: 20/05/2015 Ora: 10.12.58 Valori Agricoli Medi della provincia Annualità 2014 Dati Pronunciamento Commissione Provinciale Pubblicazione sul BUR n. del n. del REGIONE AGRARIA N°: 1 REGIONE AGRARIA N°: 2 C1 - VALLE DI FIEMME - ZONA A C1 - VALLE DI FIEMME - ZONA BC11 - VALLE DI FASSA Comuni di: CAPRIANA, CASTELLO MOLINA DI FIEMME (P), Comuni di: CAMPITELLO DI FASSA, CANAZEI, CARANO, CASTELLO VALFLORIANA MOLINA DI FIEMME (P), CAVALESE, DAIANO, MAZZIN, MOENA, PANCHIA`, POZZA DI FASSA, PREDAZZO, SORAGA, TESERO, VARENA, VIGO DI FASSA, ZIANO DI FIEMME COLTURA Valore Sup. > Coltura più Informazioni aggiuntive Valore Sup. > Coltura più Informazioni aggiuntive Agricolo 5% redditizia Agricolo 5% redditizia (Euro/Ha) (Euro/Ha) BOSCO - CLASSE A: BOSCO CEDUO 16000,00 21-BOSCO CEDUO CLASSE A - 16000,00 21-BOSCO CEDUO CLASSE A - BOSCO A CEDUO FERTILE) BOSCO A CEDUO FERTILE) BOSCO - CLASSE A: BOSCO DI FUSTAIA 25000,00 18-BOSCO FUSTAIA CLASSE A 25000,00 18-BOSCO FUSTAIA CLASSE A - BOSCO A FUSTAIA CON - BOSCO A FUSTAIA CON TARIFFA V IV E III) TARIFFA V IV E III) BOSCO - CLASSE B: BOSCO CEDUO 12000,00 22-BOSCO CEDUO CLASSE B - 12000,00 22-BOSCO CEDUO CLASSE B - BOSCO A CEDUO BOSCO A CEDUO MEDIAMENTE FERTILE) MEDIAMENTE FERTILE) BOSCO - CLASSE B: BOSCO DI FUSTAIA 18000,00 19-BOSCO FUSTAIA CLASSE B 18000,00 19-BOSCO FUSTAIA CLASSE B - BOSCO A FUSTAIA CON - BOSCO A FUSTAIA CON TARIFFA VII E VI) TARIFFA VII E VI) BOSCO - CLASSE C: BOSCO CEDUO 9000,00 23-BOSCO CEDUO CLASSE C - 9000,00 23-BOSCO CEDUO CLASSE C - BOSCO A CEDUO POCO BOSCO A CEDUO POCO FERTILE) FERTILE) BOSCO - CLASSE C: BOSCO DI FUSTAIA 12000,00 20-BOSCO FUSTAIA CLASSE C 12000,00 20-BOSCO FUSTAIA CLASSE C - BOSCO A FUSTAIA CON - BOSCO A FUSTAIA CON TARIFFA VIII E IX) TARIFFA VIII E IX) Pagina: 1 di 81 Ufficio del territorio di TRENTO Data: 20/05/2015 Ora: 10.12.58 Valori Agricoli Medi della provincia Annualità 2014 Dati Pronunciamento Commissione Provinciale Pubblicazione sul BUR n. -

Communication and Dissemination Plan

BELLUNO PILOT AREAS REPORT INTRODUCTION FUTOURIST is pursuing new and innovative approaches satisfying the increasing demand of a natural tourism and the need of people to live a really intense experience among nature. The project faces the growing importance of sustainable activities to guarantee a soft tourism and the economic and social stability of a region. It also promotes an untouched landscape, as a base for an almost natural tourism. The project aims at municipalities, locations and regions that are less exploited by tourism and are located outside of conservation areas such as the National Park and Nature Parks. To realize the goals of FUTOURIST, that were approved by the authority, the following requirements were defined in the first step of the process of pilot region identification. • Presence of characteristic and special natural and/or cultural landscapes or features that are suitable “to be put in scene”; • Relation to locals who are engaged in conserving natural and/or cultural landscapes or features and/or are interested in communicating and transmitting knowledge or experience • Location outside of existing conservation areas • Perspective to pursue a nature-compatible and eco-friendly tourism that is in harmony with nature • Absence of hard touristic infrastructure and touristic exploitation Project partners defined 20 criteria in the categories morphology & infrastructure, nature & culture, tourism, economy and players for the selection of the potential pilot areas in order to guarantee sustainability to the project and ensure continuation of the activities. FUTOURIST provides for the identification in the province of Belluno of three experimental area that better respond to these criteria and in which sustainable tourism can be practiced The needs of the local stakeholders have been gathered during various meetings, the analysis and the drafting developed by DMO Dolomiti and the presentation of the plan commissioned at Eurac Research have been taken into consideration. -

The Dolomites a Guided Walking Adventure

ITALY The Dolomites A Guided Walking Adventure Table of Contents Daily Itinerary ........................................................................... 4 Tour Itinerary Overview .......................................................... 13 Tour Facts at a Glance ........................................................... 16 Traveling To and From Your Tour .......................................... 18 Information & Policies ............................................................ 23 Italy at a Glance ..................................................................... 25 Packing List ........................................................................... 30 800.464.9255 / countrywalkers.com 2 © 2017 Otago, LLC dba Country Walkers Travel Style This small-group Guided Walking Adventure offers an authentic travel experience, one that takes you away from the crowds and deep in to the fabric of local life. On it, you’ll enjoy 24/7 expert guides, premium accommodations, delicious meals, effortless transportation, and local wine or beer with dinner. Rest assured that every trip detail has been anticipated so you’re free to enjoy an adventure that exceeds your expectations. And, with our optional Flight + Tour Combo and Venice PostPost----TourTour Extension to complement this destination, we take care of all the travel to simplify the journey. Refer to the attached itinerary for more details. Overview Dramatic pinnacles of white rock, flower-filled meadows, fir forests, and picturesque villages are all part of the renowned Italian Dolomites, protected in national and regional parks and recently recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage site. The luminous limestone range is the result of geological transformation from ancient sea floor to mountaintop. The region is a landscape of grassy balconies perched above Alpine lakes, and Tyrolean hamlets nestled in lush valleys, crisscrossed by countless hiking and walking trails connecting villages, Alpine refuges, and cable cars. The Dolomites form the frontier between Germanic Northern Europe and the Latin South.