GIPE-023945.Pdf (8.822Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jorunn Bjørgum Veien Til Komintern Martin Tranmæl Og Det

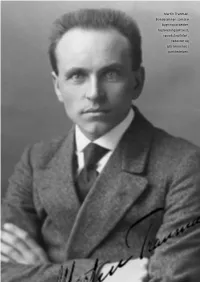

Martin Tranmæl. Bondesønnen som ble bygningsarbeider, fagforeningsaktivist, sosialistagitator , redaktør og grå eminense i partiledelsen. Jorunn BJørguM Veien til Komintern Martin Tranmæl og det internasjonale spørsmål 1914–19 Hvordan kan vi forklare at Martin Tranmæl i 1919 gikk inn for at Det norske Arbeiderparti skulle bryte opp fra den gamle sosialistiske 2. Inter nasjonalen og i stedet slutte seg til Komintern? Det er hovedproblemstil lingen i denne artikkelen.1 Martin Tranmæl var en ruvende lederskikkelse i norsk arbeiderbeve gelse i over to mannsaldre. Forut for 1918 var han opposisjonsleder. gjennom hele mellomkrigstiden var han Arbeiderpartiets reelle politiske leder. og i etterkrigstiden var han en sentral politisk bakspiller eller grå eminense i partiledelsen. Han var medlem av Arbeiderpartiets landsstyre fra 1906 og av sentralstyret fra 1918 og helt fram til 1963. I storparten av tiden var han også medlem av Los sekretariat og av samarbeids komiteen mellom Arbeiderpartiet og Lo.2 Han utøvde sitt lederskap dels gjennom de formelle organene han deltok i, dels gjennom stillingen som redaktør og dels gjennom personlig påvirkning på partiformennene oscar Torp og Einar gerhardsen, som han selv hadde rekruttert til parti ledelsen i 1923. Så hvordan kunne det ha seg at denne sentrale sosialdemokraten i 1919 gikk inn for at Arbeiderpartiet skulle melde seg inn i Lenins nye kommunistiske internasjonale? utgangspunktet var radikaliseringen av norsk arbeiderbevegelse under første verdenskrig, da Tranmæl stod i spissen for partiopposisjonen, den nye retning. Den overtok ledelsen av Arbeiderpartiet på landsmøtet i 1918 og fikk vedtatt sin parole revolu sjonær masseaksjon som partiets nye politiske strategi.3 Tranmæl ble ny partisekretær og hans nære venn og politiske medarbeider, Kyrre grepp, ny partiformann. -

Martin Tranmæl, Sentral Person I Jorunn Bjørgums Tanker Rundt Oppgaven Å Skrive Arbeider- Bevegelsens Historie

Martin Tranmæl, sentral person i Jorunn Bjørgums tanker rundt oppgaven å skrive arbeider- bevegelsens historie. 146 JORUNN BJØRGUM Forskning i arbeiderbevegelsens historie Et tilbakeblikk og et framtidsperspektiv Hvordan tenker jeg arbeiderbevegelsens historie bør skrives framover. Hva er gjort, hva må gjøres? Slik lød den første formuleringen av oppgaven. Lenin salig ihukommelse. Avgrensningen til hva jeg mener bør gjøres, er nok fornuftig. For noen ordentlig redegjørelse for hva som er gjort, ville selvsagt sprengt rammen fullstendig. Men uansett må jeg jo ta utgangspunkt i hvor vi kommer fra for å kunne tenke omkring hvor vi skal videre. Derfor starter jeg likevel med historien, eller rettere med historiografien – det vil si med min egen del av den, med min egen utvik- ling som forsker. Jeg fortolker altså oppgaven jeg har fått til «hva har jeg gjort og hva synes jeg bør gjøres» i forlengelsen av det. Som stikkord for det jeg skal si, vil jeg bruke Martin Kolbergs plagiat av Martin Tranmæl: fagbevegelsen, fagbevegelsen, fagbevegelsen. Først og fremst er det på fagbevegelsens historie jeg vil mene kreftene bør settes inn i tiden framover. En grunn til dette er min egen faglige, det vil si historiefaglige, inter- esse. Det var jo med fagbevegelsen jeg i sin tid startet som forsker, ble tent og bevarte interessen videre. Etter historie hovedfagseksamen høsten 1968, begynte jeg som oppdragsforsker, engasjert av et av LO-forbundene, Norsk Kjemisk Industriarbeiderforbund, til å skrive en historisk framstilling i anledning forbundets forestående 50-årsjubileum i 1973. Kjemisk var stiftet i 1923 som resultat av at LO-kongressen samme år hadde vedtatt omlegging av organisasjonsformen fra fagforbund til industriforbund. -

Masteroppgave I Historie for Ingrid Lastein Hansen

Arbeiderpartiet og krisepolitikken i mellomkrigsårene En analyse av hovedlinjene i Arbeiderpartiets krisepolitiske syn, med utgangspunkt i Nygaardsvold-regjeringens krisepolitikk i perioden 1935-1938 Ingrid Lastein Hansen Masteroppgave i historie Høst 2010 Institutt for arkeologi, konservering og historie (IAKH) Universitetet i Oslo (UiO) Forord Denne oppgaven har blitt til gjennom en lang og krevende prosess. Først og fremst vil jeg takke veileder Einar Lie for gode faglige innspill, tilgjengelighet og ikke minst tålmodighet. En takk går også til familie og venner for oppmuntrende ord underveis. Arkivpersonalet på Riksarkivet fortjener en takk for informativ veiledning i arkivet. Til slutt vil jeg takke Odin for lange fine turer og et entusiastisk nærvær. Kragerø, 12. november, 2010, Ingrid Lastein Hansen 1 Innholdsfortegnelse Kapittel 1. Innledning .............................................................................................................. 4 1.1 Tema og problemstilling .................................................................................................. 4 1.2 Fremgangsmåte og begrepsavklaring............................................................................... 5 1.3 Tidligere fremstillinger .................................................................................................... 6 1.4 Kilder................................................................................................................................ 8 1.5 Disposisjon.................................................................................................................... -

Småbrukarorganisering Og Arbeidarrørsle*)

Tidsskrift for arbeiderbevegelsens historie, 1. 1980. Sigvart Tøsse Småbrukarorganisering og arbeidarrørsle*) I 1938 skreiv historikaren Wilhelm Keilhau at småbrukarane sin oppmarsj var «den mest bemerkede kjensgjerning i det norske jordbruks utviklingshistorie mellom 1905 og 1914».'). Eit resul tat av denne oppmarsjen var danninga av Norsk Småbrukerfor- bund i 1913. Artikkelen vil ta opp bakgrunnen for denne organi- sasjonsdanninga og utviklinga fram til slutten av 1920 åra. I tiåret før første verdenskrig skjedde også gjennombrotet for fagorganisasjonen og Det norske arbeiderparti. I 1912 organi serte skog- og landarbeidarane seg i eit eige forbund som slutta seg til Arbeidernes faglige landsorganisasjon. I Småbrukarfor- bundet dominerte folk frå Arbeidardemokratane. Den geograf iske basisen for begge forbunda var Austlandet, serleg Hedmark og Oppland. Småbrukarforbundet fekk ikkje den store tilslut ninga, men klarte seg over ei nedgangstid i 20 åra og byrjinga av 30 talet. Norsk skog- og jordbruksarbeiderforbund frå 1912 gjekk derimot i oppløysing i byrjinga av 1920 talet. Politisk var Arbeidarpartiet på frammarsj. Det store gjennombrotet på byg dene i Austlandet kom ved valet i 1927 som viser masseover- gang frå dei tidlegare arbeidardemokratveljarane. Eit interessant aspekt som vil bli teke opp her, er da tilhøvet mellom småbruka- rorganisasjonen og arbeidarrørsla. Men først spør vi om kvifor Norsk Småbrukerforbund blei danna, og kva var dei økonomi ske, sosiale og politiske føresetnadene for ein slik organisasjon? *) Artikkelen byggjer vesentleg på hovudoppgåva mi i historie-. Norsk bonde- og småbrukarlag 1913-28. Bakgrunn og verksemd. Trondheim 1976. Økonomisk og sosial bakgrunn Jordbrukstellinga i 1907 - den første serskilte jordbrukstellinga - viste store endringar frå tidlegare statistiske oversikter. Stats minister Gunnar Knudsen sa at tellinga opna augo hans for kor utprega eit småbruksland Norge var. -

Beretning 1938

DET NORSKE ARBEIDERPARTI BERETNING 1938 UTARBEIDET VED PARTIKONTORET , o LO 1939 ARB EID ER X E S•. \ K TIE T R Y K K ER I I HOLD FORTEG EL E Side Cenlralstyret og landsstyret ..... ...... .......... 4 Partikon toret 5 Representasjon ........ ........... ............... 5 Utvalg og komiteer ....... ..... ................... 6 Orgarusasjonsoversikt . .. .. .. 7 Agitasjonen . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 8 Foredragsturneer . 9 Enkeltforedrag . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. ... 13 1ste Maidagen . ........ .... ...... ... ............... 18 Det nordiske samarbeid ........... ............... 26 Den Sosialistiske Arbeiderinternasjonale ...... .... 27 Vedlak av landsstyret .... ............... ........... 30 Conrad Mohrs Legat ............................. 33 Arbeiderbevegelsens monument ... .... ............. 33 Forhandlinger med Norges kommunistiske Parti om samling ......................... .............. 33 Arbeiderbladet . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 37 Arbeidernes Pressekontor 38 Arbeiderbevegelsens pressefond . .. .. .. 38 Det 20. århundre .................................... 38 Partipressen . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. ... 38 By- og herredslaget ......... ...................... 40 Kvinnesekretariatet . .. .. .. .. .... .. 42 Agitasjonen i hær og flåte . ........................ 45 Arbeidernes Ungdomsfylking ........................ 46 Fram-Fylkingen . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 48 Sosialistisk Skolelag . ............................... 52 Arbeiderbevegelsens Arkiv ............. ......... 53 Arbeidernes Justisfond ...................... ..... -

Beretning 1913

.. " . DET NORSKE ARBEIDERPARTI ........................................................................................................ BERETNINGFOR 1913 I AARET UT ARBEIDET VED SEKRET ÆREN I Il'i ,, ........................................................................................................ KRISTIANIA 1914 :: ARBEIDERNES AKTIETRYKKERI Indholdsfortegnelse. Centralstyrets beretning. ide Hedemarken. 'ide Solør arbeiderparti . 28 .\.aret 1913 (over igt . 1 Eidskog, Vinger og Odalen arb.p. 30 Landsstyret . 2 . Søndre Hedemarkens kredsparti 30 Centralstyret . 2 Nordre Hedemarkens arb.parti . 31 Nye organisationer . 2 Søndre Østerdalen arb.parti . 31 Strøkne organisationer . 3 Xordre Østerdalens kredsparti 32 Amtspartternes omorganisation . 3 Kristian. 1. 8maalene amtsparti . 3 Jevnaker arbeiderparti . 32 2. Akershus amtsparti ... 4 Bu�kerud. 3. Hedemarkens amt parti . 4 Buskerud amtsparti . 33 4. Buskerud amtsparti . 5 Numedals kredsparti . 35 5. Brat berg amtsparti . 5 Jarlsberg og Larvik. Agitationen . 5 koger kred arbeiderparti . 35 1. mai .. ...... 9 Brunla kredsparti . 35 Kommunevalgene . 9 Bratsberg. 1. Landkommunerne . 10 Brat berg amtsparti . 36 2. Byerne . 11 Vest-Telemarkens kred parti 37 3. ICvinderne og valget . 11 Nedenes. 4. Valgets hovedre ultat 12 Nedene amtsparti . 37 Brochurer . 13 Lister og Man dal. Partiets forlag og bokhandel . 14 Oddernes kreds arbeiderparti 38 Det tyvende aarhundrede . 15 .Mandalens kred sparti . 38 Kommunalt tidssknft . 15 Stavanger amt. Partiet pre se . 15 Stavanger amtsparti . 38 Haand -

Centre for Peace Studies Faculty of Humanities, Social Sciences and Education

Centre for Peace Studies Faculty of Humanities, Social Sciences and Education The portrayal of the Russian Revolution of 1917 in the Norwegian labor movement A study of the editorials of the Social-Demokraten, 1915—1923 Anzhela Atayan Master’s thesis in Peace and Conflict Transformation – SVF-3901 June 2014 ii Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisor Kari Aga Myklebost for helpful supervision with practical advice and useful comments, the Culture and Social Sciences Library, the Centre for Peace Studies and Ola Goverud Andersson for support. iii iv Morgen mot Russlands grense Jeg kommer fra dagen igår, fra vesten, fra fortidens land. Langt fremme en solstripe går mot syd. Det er morgenens rand. I jubel flyr toget avsted. Se grensen! En linje av ild. Bak den er det gamle brendt ned. Bak den er det nye blitt til. Jeg føler forventningens sang i hjertets urolige slag. Så skulde jeg også engang få møte den nye dag! Rudolf Nilsen v vi Table of Contents Chapter 1. Introduction…………………………………………………………………….......1 1.1.Major terms and choice of period……...………………………………………………......1 1.2.Research questions…………………………………………………………………………2 1.3.Motivation and relevance for peace studies………………………………………………..3 1.4.Three editors: presentation…………………………………………………………………3 1.5.The development of the Norwegian labor press: a short description………………………6 1.6.The position of the Norwegian labor movement in Scandinavia…………………………..7 1.7.Structure of the thesis............................................................................................................8 Chapter 2. Previous studies and historical background………………………………………11 2.1. Previous studies…………………………………………………………………………..11 2.2. Historical background……………………………………………………………………14 2.2.1. The situation in Norway…………………………………………………………...14 2.2.2. Connections between the Bolsheviks and the Norwegian left…………….……....16 Chapter 3. -

Den Skjulte Makten

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by NORA - Norwegian Open Research Archives Den skjulte makten Ingjald Nissen og hans samfunnskritikk Av Haakon Flemmen Masteroppgave i idéhistorie Institutt for filosofi, idé- og kunsthistorie og klassiske språk UNIVERSITETET I OSLO Våren 2010 ii Sammendrag Filosofen og psykologen Ingjald Nissen (1896–1977) var i flere tiår en markant skikkelse i norsk offentlighet. Han var kjent for sine oppsiktsvekkende teorier, omstridte bøker og hissige polemikker. Gjennom mellom- og etterkrigstiden satte han sitt preg på flere viktige samfunnsdebatter, og han regnes i dag som en tidlig representant for feministisk filosofi. Likevel er Nissens store og uvanlige forfatterskap blitt stående uutforsket og upåaktet av historikere. Med denne oppgaven kastes det for første gang lys over denne originale og kontroversielle figuren i norsk idéhistorie. Denne oppgaven viser at Ingjald Nissen var en sentral aktør i flere av sin tids mest intense offentlige ordskifter – om Freuds psykoanalyse, nazismens natur, de kontroversielle Kinsey-rapportene, mannssamfunnet og den «usedelige» litteraturen. Hans teorier om skjult og psykologisk manipulasjon har dessuten satt varige spor. Det var Ingjald Nissen som etablerte begrepet hersketeknikk som en del av den norske offentlighetens vokabular. Et mål med oppgaven er å forklare hvordan Nissen i slutten av tjueårene kunne tilhøre et verdikonservativt miljø, for senere å bli en utpreget radikal stemme i samfunnsdebatten. Jeg argumenterer for at denne radikaliseringen ble drevet frem både av Nissens teoretiske utvikling, hans rolle som samfunnsdebattant og hans forhold til ulike miljøer. Oppgavens første kapittel tar for seg en tidlig fase av Nissens forfatterskap, da han tilhørte den konservative kretsen rundt nyhumanisten A.H. -

Literaturverzeichnis

Literaturverzeichnis Die Literaturliste folgt der deutschen Alphabetisierung, d.h.: aa und a, werden an den Beginn und nicht an das Ende des Alphabetes gestellt, die Umlaute ce und 0 als ä und ö behandelt. Examensarbeiten, hovedoppgaver, die nicht über den Buchhandel erhältlich sind, sondern nur in Universitäts- und Institutsbibliotheken bzw. dem Archiv der Arbeiterbewegung eingesehen werden können, sind mit * gekennzeichnet, während die publizierten Ex amensarbeiten mit -+ versehen sind. -+ Knut Aagesen, Fagopposisjonen av 1940 [Die Gewerkschaftsopposition von 1940], in: 1940 - Fra n0ytral ti1 okkupert [1940 - von neutral bis okkupiert], Oslo 1969 * 0yvind Aasmul, Bruddet i Bergens arbeiderparti i 1923 [Die Spaltung in der Arbeiterpartei in Bergen 1923], Universität Bergen 1977 * Ame Alnces, So1kjerringer og fiskbcerere. Om arbeideme pä klippfiskbcergan i Kristiansund pä 1930-tallet [Sonnenweiber und Fischträger. Über die Arbeiter auf den Trockenfisch klippen in Kristiansund in den 1930er Jahren], Universität Trondheim 1982 Hans Amundsen, Christofer Homsrud, Oslo 1939 Ders., Trygve Lie - gutten fra Grorud som ble generalsekretcer i FN [Trygve Lie-der Junge aus Grorud, der UNO-Generalsekretär wurde], Oslo 1946 * Trond Amundsen, Fiskerkommunismen i nord: Vilkarene for kommunistenes oppslutning pä kysten av 0st-Finnmark i perioden 1930-1940 [Fischereikommunismus im Norden: Bedingungen für die Zustimmung für die Kommunisten in den Küstengebieten von Ost-Finnmark in der Periode 1930-1940], Universität Troms0 1991 Haakon With Andersen, Kapitalisme med menneskelig ansikt ? Fra akkord ti1 fast 10nn ved Akers Mek. Verksted i 1957 [Kapitalismus mit menschlichem Gesicht ? Von Akkord zu festem Gehalt in Akers Mechanischen Werkstätten im Jahre 1957], in: Tidsskrift for arbeiderbevegelsens historie, 2 ( 1981) Roy Andersen, Sin egen fiende. Et portrett av Asbj0rn Bryhn [Sein eigener Feind. -

Finn Moe - En Utenrikspolitisk Biografi

1 Finn Moe - en utenrikspolitisk biografi Vebjørn Kristen Elvebakk Hovedfagsoppgave i historie Universitetet i Oslo, Historisk institutt Høsten 2004 2 Forord Først og fremst vil jeg takke Knut Einar Eriksen for konstruktiv og hyggelig veiledning gjennom hele dette arbeidet. Takk fortjener også alle ved NUPI, herunder spesielt Erik Nord, Andreas Selliaas, John Kristen Skogan og personalet ved biblioteket. Sven Holtsmark ved IFS har sjenerøst stilt sitt private arkiv til disposisjon og vært en god rådgiver og samtalepartner. Min medstudent Nils August Andresen har kyndig foretatt nødvendige oversettelser fra russisk til norsk. Takk også til Guri Hjeltnes, Finn Olstad og Even Lange som har kommet med gode faglige råd og interessant informasjon. Halvard Fossheim ved Filosofisk institutt, UiO har bistått meg med oversettelse fra fransk og fortolkning av Finn Moes gullmedaljeoppgave. Beate Elvebakk har foreslått språklige forbedringer og ellers gitt mange nyttige tips og vink. Takk også til alle som i sin travle hverdag har latt seg intervjue. Endelig må jeg fremheve imøtekommenheten fra personalet ved Arbeiderbevegelsens Arkiv og Bibliotek, Nasjonalbiblioteket, Riksarkivet, Stortingsarkivet og Utenriksdepartementets arkiv. Aller mest takk til Elen. Oslo, 16.10.2004. Vebjørn Elvebakk 3 Innholdsfortegnelse Innledning 4 Oppgavens bakgrunn og problemstilling 4 Kapittel 5: Avgrensning og struktur 6 Tøvær og tro på forandring (1955-1964) 90 Betraktninger rundt metode og sjanger 8 Nye premisser 91 Litteratur 10 Konvergens og atomtrusselens perspektiver -

Nordic Narratives of the Second World War : National Historiographies Revisited

Nordic Narratives of the Second World War : National Historiographies Revisited Stenius, Henrik; Österberg, Mirja; Östling, Johan 2011 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Stenius, H., Österberg, M., & Östling, J. (Eds.) (2011). Nordic Narratives of the Second World War : National Historiographies Revisited. Nordic Academic Press. Total number of authors: 3 General rights Unless other specific re-use rights are stated the following general rights apply: Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Read more about Creative commons licenses: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. LUND UNIVERSITY PO Box 117 221 00 Lund +46 46-222 00 00 Download date: 01. Oct. 2021 nordic narratives of the second world war Nordic Narratives of the Second World War National Historiographies Revisited Henrik Stenius, Mirja Österberg & Johan Östling (eds.) nordic academic press Nordic Academic Press P.O. Box 1206 SE-221 05 Lund, Sweden [email protected] www.nordicacademicpress.com © Nordic Academic Press and the authors 2011 Typesetting: Frederic Täckström www.sbmolle.com Cover: Jacob Wiberg Cover image: Scene from the Danish movie Flammen & Citronen, 2008. -

Who Needs Norwegians?" Explaining the Oslo Back Channel: Norway’S Political Past in the Middle East

Evaluation Report 9/2000 Hilde Henriksen Waage "Norwegians? Who needs Norwegians?" Explaining the Oslo Back Channel: Norway’s Political Past in the Middle East A report prepared by PRIO International Peace Research Institute, Oslo Institutt for fredsforskning Responsibility for the contents and presentation of findings and recommendations rests with the author. The views and opinions expressed in the report do not necessarily correspond with the views of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Preface In September 1998, I was commissioned by the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs to carry out a preliminary study looking into Norway’s role in the Middle East. According to the agreement with the Ministry, the study should focus on the years prior to 1993 and examine whether Norway’s political past in the Middle East – and, not least, the mediating and confidence-building efforts of Norwegians prior to the opening of the secret Oslo Back Channel – had had any influence on the process that followed. The study should also try to answer the question ‘Why Norway?’ – that is, what had made Norway, of all countries, suitable for such an extraordinary task? The work on the study started on 15 September 1998. The date of submission was stipulated as 15 April 2000. This was achieved. The following report is based on recently declassified and partly still classified documents (to which I was granted access) at the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the verbatim records of the Parliamentary Foreign Affairs Committee, records of government proceedings and the Norwegian Parliament, Labour Party Archives, documents from the US State Department and the Socialist International – to mention the most important.