The Collapse of Sensemaking in Organizations: the Mann Gulch Disaster

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eerie Archives: Volume 16 Free

FREE EERIE ARCHIVES: VOLUME 16 PDF Bill DuBay,Louise Jones,Faculty of Classics James Warren | 294 pages | 12 Jun 2014 | DARK HORSE COMICS | 9781616554002 | English | Milwaukee, United States Eerie (Volume) - Comic Vine Gather up your wooden stakes, your blood-covered hatchets, and all the skeletons in the darkest depths of your closet, and prepare for a horrifying adventure into the darkest corners of comics history. This vein-chilling second volume showcases work by Eerie Archives: Volume 16 of the best artists to ever work in the comics medium, including Alex Toth, Gray Morrow, Reed Crandall, John Severin, and others. Grab your bleeding glasses and crack open this fourth big volume, collecting Creepy issues Creepy Archives Volume 5 continues the critically acclaimed series that throws back the dusty curtain on a treasure trove of amazing comics art and brilliantly blood-chilling stories. Dark Horse Comics continues to showcase its dedication to publishing the greatest comics of all time with the release of the sixth spooky volume Eerie Archives: Volume 16 our Creepy magazine archives. Creepy Archives Volume 7 collects a Eerie Archives: Volume 16 array of stories from the second great generation of artists and writers in Eerie Archives: Volume 16 history of the world's best illustrated horror magazine. As the s ended and the '70s began, the original, classic creative lineup for Creepy was eventually infused with a slew of new talent, with phenomenal new contributors like Richard Corben, Ken Kelly, and Nicola Cuti joining the ranks of established greats like Reed Crandall, Frank Frazetta, and Al Williamson. This volume of the Creepy Archives series collects more than two hundred pages of distinctive short horror comics in a gorgeous hardcover format. -

Preacher Fire

Preacher Fire Fuels and Fire Behavior Resulting in an Entrapment July 24, 2017 Facilitated Learning Analysis (FLA) Photo Courtesy of BLM BLM Carson City District Office, Nevada Table of Contents Page Executive Summary ------------------------------------------------------------------------- 2 Methods ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ 2 Report Structure -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 3 Conditions Affecting the Preacher Fire ------------------------------------------------- 3 Fuel Conditions --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------3 Fire Suppression Tactics -------------------------------------------------------------------------- 4 Weather Conditions -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 4 Communication Challenges ----------------------------------------------------------------------- 4 Previous Fire History and Map ------------------------------------------------------------------- 4 The Story --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 5 Lessons Learned, Observations & Recommendations from Participants ---- 16 Fuel Conditions and Fire Behavior -------------------------------------------------------------- 16 Communications ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 17 Aviation -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- -

Escape Fire: Lessons for the Future of Health Care

Berwick Escape Fire lessons for the future oflessons for the future care health lessons for the future of health care Donald M. Berwick, md, mpp president and ceo institute for healthcare improvement ISBN 1-884533-00-0 the commonwealth fund Escape Fire lessons for the future of health care Donald M. Berwick, md, mpp president and ceo institute for healthcare improvement the commonwealth fund new york, new york The site of the Mann Gulch fire, which is described in this book, is listed introduction in the National Register of Historic Places. Because many regard it as sacred ground, it is actively protected and managed by the Forest Service as a cultural landscape. On December 9, 1999, the nearly 3,000 individuals who attended the 11th Annual National Forum on Quality Improvement in Health Care heard an extraordinary address by Dr. Donald M. Berwick, the founder, president, and CEO of the Institute for Healthcare Improvement, the forum’s sponsor. Entitled Escape Fire, Dr. Berwick’s speech took its audience back to the year 1949, when a wildfire broke out on a Montana hillside, taking the lives of 13 young men and changing the way firefighting was managed in the United States. After retelling this harrowing tale, Dr. Berwick applied the Escape Fire is an edited version of the Plenary Address delivered at the Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s 11th Annual National Forum lessons learned from this catastrophe to the health care on Quality Improvement in Health Care, in New Orleans, Louisiana, on December 9, 1999. system—a system that, he believes, is on the verge of its Copyright © 2002 Donald M. -

National Register of Historic Places Continuation Sheet

NFS Form 10-900-a OMB Approval No. 1024-O01B (8-86) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Continuation Sheet Section number ——— Page ——— SUPPLEMENTARY LISTING RECORD NRIS Reference Number: 99000596 Date Listed: 5/19/99 Mann Gulch Wildfire Historic District Lewis & Clark MT Property Name County State N/A Multiple Name This property is listed in the National Register of Historic Places in accordance with the attached nomination documentation subject to the following exceptions, exclusions, or amendments, notwithstanding the National Park Service certification included in the nomination documentation. Signature/of /-he Keeper Date of Action Amended Items in Nomination: U. T. M. Coordinates: U. T. M. coordinates 1 and 2 are revised to read: 1) 12 431300 5190880 2) 12 433020 5193740 This information was confirmed with C. Davis of the Helena National Forest, MT. DISTRIBUTION: National Register property file Nominating Authority (without nomination attachment) NPS Form 10-900 No. 1024 0018 (Rev. Oct. 1990) RECEIVED 2/ United States Department of the Interior National Park Service 20BP9 NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLA :ESJ REGISTRATION FORM 1. Name of Property historic name: Mann Gulch Wildfire Historic District other name/site number: 24LC1160 2. Location street & number: Mann Gulch, a tributary of the Missouri River, Helena National Forest not for publication: na vicinity: X city/town: Helena state: Montana code: Ml county: Lewis and Clark code: 049 zip code: 59601 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1986, as amended, I hereby certify that this X nomination _ request for determination of eligibilityj^eejsjhe documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professj^rafrequirernente set Jfortjjin 36 CFR Part 60. -

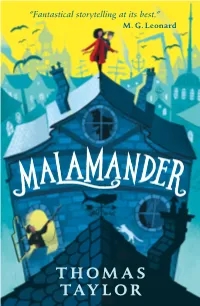

Malamander-Extract.Pdf

“Fantastical storytelling at its best.” M. G. Leonard THOMAS TAYLOR THOMAS TAYLOR This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents are either the product of the author’s imagination or, if real, used fictitiously. All statements, activities, stunts, descriptions, information and material of any other kind contained herein are included for entertainment purposes only and should not be relied on for accuracy or replicated as they may result in injury. First published 2019 by Walker Books Ltd 87 Vauxhall Walk, London SE11 5HJ 2 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 Text and interior illustrations © 2019 Thomas Taylor Cover illustrations © 2019 George Ermos The right of Thomas Taylor to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 This book has been typeset in Stempel Schneider Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon CR0 4YY All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, transmitted or stored in an information retrieval system in any form or by any means, graphic, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, taping and recording, without prior written permission from the publisher. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data: a catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978-1-4063-8628-8 (Trade) ISBN 978-1-4063-9302-6 (Export) ISBN 978-1-4063-9303-3 (Exclusive) www.walker.co.uk Eerie-on-Sea YOU’VE PROBABLY BEEN TO EERIE-ON-SEA, without ever knowing it. When you came, it would have been summer. -

READY, SET, GO! Montana Your Personal Wildland Fire Action Guide

READY, SET, GO! Montana Your Personal Wildland Fire Action Guide READY, SET, GO! Montana Wildland Fire Action Guide Saving Lives and Property through Advanced Planning ire season is now a year-round reality in many areas, requiring firefighters and residents to be on heightened alert for the threat of F wildland fire. This plan is designed to help you get ready, get set, and INSIDE go when a wildland fire approaches. Civilian deaths occur because people wait too long to leave their home. Each year, wildland fires consume hundreds of homes in the Wildland-Urban Living in the Wildland-Urban Interface 3 Interface (WUI). Studies show that as many as 80 percent of the homes lost to wildland fires could have been saved if their owners had only followed a few simple fire-safe practices. Give Your Home a Chance 4 Montana wildland firefighting agencies and your local fire department take every precaution to help protect you and your property from wildland fire. Making a Hardened Home 5 However, the reality is that in a major wildland fire event, there will simply not be enough fire resources or firefighters to defend every home. Successfully preparing for a wildland fire enables you to take personal Tour a Wildland Fire Ready Home 6-7 responsibility for protecting yourself, your family and your property. In this Ready, Set, Go! Action Guide, our goal is to provide you with the tips and tools you need to prepare for a wildland fire threat, to have situational awareness Ready – Preparing for the Fire Threat 8 when a fire starts, and to leave early when a wildland fire threatens, even if you have not received a warning. -

Appendix E: Sample Burn Plan Refuge Or Station: San Francisco Bay NWR Complex Unit

Appendix E: Sample Burn Plan Refuge or Station: San Francisco Bay NWR Complex Unit : Antioch Dunes NWR 11646 Date: Prepared By: Date: Roger P. Wong Prescribed Fire Burn Boss Reviewed By: Date: ADR Assistant Refuge Manager The approved Prescribed Fire Plan constitutes the authority to burn, pending approval of Section 7 Consultations, Environmental Assessments, or other required documents. No one has the authority to burn without an approved plan or in a manner not in compliance with the approved plan. Prescribed burning conditions established in the plan are firm limits. Actions taken in compliance with the approved Prescribed Fire Plan will be fully supported, but personnel will be held accountable for actions taken which are not in compliance with the approved plan. Approved By: Date: Margaret Kolar Project Leader San Francisco Bay/Don Edwards NWR 85 PRESCRIBED FIRE PLAN Refuge: San Francisco Bay NWR Complex Refuge Burn Number: Sub Station: Antioch Dunes NWR Fire Number: Name of Areas: Stamm Unit Total Acres To Be Burned: 11 acres divided into 2 units to be burned over one day Legal Description: Stamm Unit T.2N; R.2E, Section 18 Lat. 38 01', Long. 121 48' Is a Section 7 Consultation being forwarded to Fish and Wildlife Enhancement for review? Yes No (circle). Biological Opinion dated June 11, 1997 (Page 2 of this PFP should be a refuge base map showing the location of the burn on Fish and Wildlife Service land.) The Prescribed Fire Burn Boss/Specialist must participate in the development of this plan. I. GENERAL DESCRIPTION OF BURN UNIT Physical Features and Vegetation Cover Types Burn Unit 1B -- Stamm Unit - Hardpan (4 acres): Predominantly annual grasses interspersed with YST and bush lupin “skeletons” from previous year’s prescribed burn. -

Since I Began Reading the Work of Steve Ditko I Wanted to Have a Checklist So I Could Catalogue the Books I Had Read but Most Im

Since I began reading the work of Steve Ditko I wanted to have a checklist so I could catalogue the books I had read but most importantly see what other original works by the illustrator I can find and enjoy. With the help of Brian Franczak’s vast Steve Ditko compendium, Ditko-fever.com, I compiled the following check-list that could be shared, printed, built-on and probably corrected so that the fan’s, whom his work means the most, can have a simple quick reference where they can quickly build their reading list and knowledge of the artist. It has deliberately been simplified with no cover art and information to the contents of the issue. It was my intension with this check-list to be used in accompaniment with ditko-fever.com so more information on each publication can be sought when needed or if you get curious! The checklist only contains the issues where original art is first seen and printed. No reprints, no messing about. All issues in the check-list are original and contain original Steve Ditko illustrations! Although Steve Ditko did many interviews and responded in letters to many fanzines these were not included because the checklist is on the art (or illustration) of Steve Ditko not his responses to it. I hope you get some use out of this check-list! If you think I have missed anything out, made an error, or should consider adding something visit then email me at ditkocultist.com One more thing… share this, and spread the art of Steve Ditko! Regards, R.S. -

Fire Management Leadership Fire Management Leadership

Fire today ManagementVolume 60 • No. 2 • Spring 2000 FIREIRE MANAGEMENT LEADERSHIPEADERSHIP United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service Through the Flames © Paco Young, 1999. Artwork courtesy of the artist and art print publisher Mill Pond Press, Venice, FL. For additional infor mation, please call 1-800-237-2233. Fire Management Today is published by the Forest Service of the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Washington, DC. The Secretary of Agriculture has determined that the publication of this periodical is necessary in the transaction of the public business required by law of this Department. Subscriptions ($13.00 per year domestic, $16.25 per year foreign) may be obtained from New Orders, Superintendent of Documents, P.O. Box 371954, Pittsburgh, PA 15250-7954. A subscription order form is available on the back cover. Fire Management Today is available on the World Wide Web at <http://www.fs.fed.us/fire/planning/firenote.htm>. Dan Glickman, Secretary April J. Baily U.S. Department of Agriculture General Manager Mike Dombeck, Chief Robert H. “Hutch” Brown, Ph.D. Forest Service Editor José Cruz, Director Fire and Aviation Management The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, gender, religion, age, disability, political beliefs, sexual orientation, or marital or family status. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, Room 326-W, Whitten Building, 1400 Independence Avenue, SW, Washington, DC 20250-9410 or call (202) 720-5964 (voice and TDD). -

Title FX Volume 2

Title FX Vol. 2 Title fx vol 2 Disc Track Index Secs Description Filename Category TFX2-01 1 1 7.4 Digital Pulse Alarm Scan Warning DigitalPulseAlarmSc TFX2001 Computers & Beeps TFX2-01 2 1 4.1 Low Heavy Text Materialize Sweep LowHvyTextMateriali TFX2002 Sci-Fi Eerie Stingers TFX2-01 3 1 3.3 Heavy Text Sliding Into Shifted Rumble Short HvyTextSlidingShift TFX2003 Sci-Fi Eerie Stingers TFX2-01 4 1 4.1 Sliding Pitch Motor By SlidingPitchMotorBy TFX2004 Sci-Fi Eerie Stingers TFX2-01 5 1 6.9 Slide Multi Whoosh Phase Pitch Looped SlideMultiWhooshPha TFX2005 Sci-Fi Eerie Stingers TFX2-01 6 1 6.5 Slide Pitch Looped Sci-Fi Motorcycles SlidePitchLoopedSci TFX2006 Sci-Fi Eerie Stingers TFX2-01 7 1 6.1 Slide Pitch Looped Sci-Fi Motorcycle Slow Pitch SlidePitchLoopedSci TFX2007 Sci-Fi Eerie Stingers TFX2-01 8 1 1.4 Low Rumble Transition LowRumbleTransition TFX2008 Sci-Fi Eerie Stingers TFX2-01 9 1 2.5 Fast Text Fade Into Low Rumble Transition FstTextFadeLowRumbl TFX2009 Sci-Fi Eerie Stingers TFX2-01 10 1 2.6 Warp Tone Modulated Fade In WarpToneModulatedFa TFX2010 Sci-Fi Eerie Stingers TFX2-01 11 1 5.9 Future Mechanical Slow By FutureMechanicalSlw TFX2011 Sci-Fi Eerie Stingers TFX2-01 12 1 2.7 Heavy Mechanical Fly Transitional By Short HvyMechanicalFlyTra TFX2012 Machines-Power Up Down TFX2-01 13 1 2.6 Mechanical Fly By Whoosh MechanicalFlyByWhoo TFX2013 Machines-Power Up Down TFX2-01 14 1 4.1 Mechanical Fly By Modulated Slow Pitch Descending Transition MechanicalFlyByModu TFX2014 Machines-Power Up Down TFX2-01 15 1 7.2 Mechanical Fly By Modulated -

“The Rook” Information Guide

The Return of “The Rook” Information Guide There is a clear void in today’s American pop culture that is The Rook. It all began in the early 1960’s. Bill, or his adventure hero alter-identity “Billy De” began working in comics before he grew his first whisker. His fascination with comic books was shared by his partner in crime Marty Arbunich. Together they created some of the very first comic book fanzines; Fantasy Hero, Fantasy Illustrated, Yancy Street Journal and Voice of Comicdom, starting at the ripe age of 14. Bill and Marty worked tirelessly to meet self-imposed deadlines as if their loyal fans relied on their publications. On one occasion Bill even snuck into Sacred Heart High School’s art room and used the Dot printer to mass produce their fanzine. Before Comic Con became the premier pop-culture comic event, there was the World Science Fiction Convention (now known as WorldCon) and in 1964 it was in Oakland. Although only 523 were in attendance, this show would have resounding impacts on Bill’s career in comics. Also in attendance was maybe the greatest science fiction fan of all time Forrest J. Ackerman, who contributed to the first science fiction fanzine, The Time Traveler. In the same year, The Time Travelers, a science fiction film, would go into production. The cast included Forry Ackerman. The Rook’s return to comics is nearly 50 years to the date of the event that would inspire Bill’s creative direction. Forrest Ackerman would later go on to create the highly popular alternative comic character Vampirella in 1969. -

Prescribed Fire Lessons Learned

Prescribed Fire Lessons Learned Escape Prescribed Fire Reviews and Near Miss Incidents Initial Impression Report June 29, 2005 Prepared by Deirdre M. Dether Submitted to Wildland Fire Lessons Learned Center Summary of Escaped Prescribed Fire Reviews and Near Miss Incidents What key lessons have been learned and what knowledge gaps exist? Introduction This analysis is the first known attempt to take a comprehensive look at escaped prescribed fire reviews and near misses. A total of 30 prescribed fire escape reviews and ‘near misses’ (see Appendix A and B) were analyzed to discover what, if any reoccurring lessons were being learned, or whether they were indicating emerging knowledge gaps or trends. It is estimated that Federal land management agencies complete between 4,000 and 5,000 prescribed fires annually. Approximately ninetynine percent of those burns were ‘successful’ (in that they did not report escapes or near misses). This can be viewed as an excellent record, especially given the elements of risk and uncertainty associated with prescribed fire. However, that leaves 40 to 50 events annually we should learn from. This report is intended to assist in that effort. Evaluating formal reviews and After Action Reviews (AAR) can be a tool for burn personnel to expand their knowledge and supplement their own direct experiences. When reviews go beyond policy and accountability questions they can provide information that can add to our own direct experiences by broadening exposure to what can occur. Learning from other experiences may help avoid undesired outcomes. The intent of this report is not to point out ‘wrong decisions’, but rather it is to use all these individual ‘events’ to see if there are common themes and/or ‘weak signals’ occurring with these escapes and near miss events.