Escape Fire: Lessons for the Future of Health Care

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Preacher Fire

Preacher Fire Fuels and Fire Behavior Resulting in an Entrapment July 24, 2017 Facilitated Learning Analysis (FLA) Photo Courtesy of BLM BLM Carson City District Office, Nevada Table of Contents Page Executive Summary ------------------------------------------------------------------------- 2 Methods ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ 2 Report Structure -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 3 Conditions Affecting the Preacher Fire ------------------------------------------------- 3 Fuel Conditions --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------3 Fire Suppression Tactics -------------------------------------------------------------------------- 4 Weather Conditions -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 4 Communication Challenges ----------------------------------------------------------------------- 4 Previous Fire History and Map ------------------------------------------------------------------- 4 The Story --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 5 Lessons Learned, Observations & Recommendations from Participants ---- 16 Fuel Conditions and Fire Behavior -------------------------------------------------------------- 16 Communications ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 17 Aviation -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- -

April 5, 2021

APRIL 5, 2021 APRIL 5, 2021 Tab le o f Contents 4 #1 Songs THIS week 5 powers 7 action / recurrents 9 hotzone / developiong 10 pro-file 12 video streaming 13 Top 40 callout 14 Hot ac callout 15 future tracks 16 INTELESCOPE 17 intelevision 18 methodology 19 the back page Songs this week #1 BY MMI COMPOSITE CATEGORIES 4.5.21 ai r p lay OLIVIA RODRIGO “drivers license” retenTion THE WEEKND “Save Your Tears” callout OLIVIA RODRIGO “drivers license” audio DRAKE “What’s Next” VIDEO CARDI B “Up” SALES BRUNO MARS/A. PAAK/SILK SONIC “Leave The Door Open” COMPOSITE OLIVIA RODRIGO “drivers license” Your weekly REsource for music research MondayMorningIntel.com CLICK HERE to E-MAIL Monday Morning Intel with your thoughts, suggestions, or ideas. mmi-powers 4.5.21 Weighted Airplay, Retention Scores, Streaming Scores, and Sales Scores this week combined and equally weighted deviser Powers Rankers. TW RK TW RK TW RK TW RK TW RK TW RK TW COMP AIRPLAY RETENTION CALLOUT AUDIO VIDEO SALES RANK ARTIST TITLE LABEL 1 10 2 10 10 8 1 OLIVIA RODRIGO drivers license Geffen/Interscope 7 1 15 12 13 10 2 THE WEEKND Save Your Tears XO/Republic 23 x 21 1 6 2 3 JUSTIN BIEBER Peaches f/Daniel Caesar/Giveon Def Jam 10 2 3 16 23 18 4 24KGOLDN Mood f/Iann Dior RECORDS/Columbia 15 x 35 5 4 3 5 BRUNO MARS/A .PAAK/SILK SONIC Leave The Door Open Aftermath Ent./Atlantic 2 9 8 34 20 13 6 BILLIE EILISH Therefore I Am Darkroom/Interscope 6 6 10 31 25 11 7 TATE MCRAE You Broke Me First RCA 4 7 7 21 17 37 8 ARIANA GRANDE 34+35 Republic 21 16 11 20 15 7 9 SAWEETIE Best Friend f/Doja -

Out with the Grungy, Socialism-Preaching City Park

volume 12 - issue 4 - tuesday, september 24, 2012 - uvm, burlington, vt uvm.edu/~watertwr - thewatertower.tumblr.com by rebeccalaurion Quick confession before we begin: I’m not a huge gamer. However, 90 percent of my friends are, and my earliest memory of my father is watching him play Final Fan- tasy. So even though I wasn’t one of the people who spent my weekend download- ing Borderlands 2 or Torchlight 2, I can still deeply appreciate what game culture has done for me. I’ve met some of my best friends through Meta-Gaming Club, and, even though I consider myself a huge geek, just in diff erent ways, gaming wasn’t exact- ly on my radar until college. As such, I’ve learned quite a bit about the world of gaming, whether I have enjoyed it or not. For one thing, a ‘gamer’ doesn’t necessarily mean an acne-ridden virgin draped in wizard robes in their mother’s basement. Th ough, that’s not to say that never happens anymore. A gamer can be anyone from someone religiously playing Angry Birds on their phone or any devoted fan waiting outside Game Stop during all hours of the night for the newest consoles ben berrick or Halo installments. by phoebefooks and patrickmurphy As a whole, I think we can all agree that stereotypes are stupid as hell. And with Vermont, and Burlington specifi cally, the primary target of the Dobrá Tea protes- es-too long-menu is a so-called “waste of gamers, there are plenty of them: they’re is known for its politically active and of- tors. -

Olivia Rodrigo's 'Sour' Returns to No. 1 on Billboard 200 Albums Chart

Bulletin YOUR DAILY ENTERTAINMENT NEWS UPDATE JUNE 28, 2021 Page 1 of 24 INSIDE Olivia Rodrigo’s ‘Sour’ Returns to • BTS’ ‘Butter’ Leads Hot 100 for Fifth No. 1 on Billboard 200 Albums Chart Week, Dua Lipa’s ‘Levitating’ Becomes BY KEITH CAULFIELD Most-Heard Radio Hit livia Rodrigo’s Sour returns to No. 1 on five frames (charts dated Jan. 23 – Feb. 20). (It’s worth • Executive of the the Billboard 200 chart for a second total noting that Dangerous had 30 tracks aiding its SEA Week: Motown Records Chairman/ week, as the album steps 3-1 in its fifth and TEA units, while Sour only has 11.) CEO Ethiopia week on the list. It earned 105,000 equiva- Polo G’s Hall of Fame falls 1-2 in its second week Habtemariam Olent album units in the U.S. in the week ending June on the Billboard 200 with 65,000 equivalent album 24 (down 14%), according to MRC Data. The album units (down 54%). Lil Baby and Lil Durk’s former • Will Avatars Kill The Radio Stars? debuted at No. 1 on the chart dated June 5. leader The Voice of the Heroes former rises 4-3 with Inside Today’s Virtual The Billboard 200 chart ranks the most popular 57,000 (down 21%). Migos’ Culture III dips 2-4 with Artist Record Labels albums of the week in the U.S. based on multi-metric 54,000 units (down 58%). Wallen’s Dangerous: The consumption as measured in equivalent album units. Double Album is a non-mover at No. -

National Register of Historic Places Continuation Sheet

NFS Form 10-900-a OMB Approval No. 1024-O01B (8-86) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Continuation Sheet Section number ——— Page ——— SUPPLEMENTARY LISTING RECORD NRIS Reference Number: 99000596 Date Listed: 5/19/99 Mann Gulch Wildfire Historic District Lewis & Clark MT Property Name County State N/A Multiple Name This property is listed in the National Register of Historic Places in accordance with the attached nomination documentation subject to the following exceptions, exclusions, or amendments, notwithstanding the National Park Service certification included in the nomination documentation. Signature/of /-he Keeper Date of Action Amended Items in Nomination: U. T. M. Coordinates: U. T. M. coordinates 1 and 2 are revised to read: 1) 12 431300 5190880 2) 12 433020 5193740 This information was confirmed with C. Davis of the Helena National Forest, MT. DISTRIBUTION: National Register property file Nominating Authority (without nomination attachment) NPS Form 10-900 No. 1024 0018 (Rev. Oct. 1990) RECEIVED 2/ United States Department of the Interior National Park Service 20BP9 NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLA :ESJ REGISTRATION FORM 1. Name of Property historic name: Mann Gulch Wildfire Historic District other name/site number: 24LC1160 2. Location street & number: Mann Gulch, a tributary of the Missouri River, Helena National Forest not for publication: na vicinity: X city/town: Helena state: Montana code: Ml county: Lewis and Clark code: 049 zip code: 59601 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1986, as amended, I hereby certify that this X nomination _ request for determination of eligibilityj^eejsjhe documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professj^rafrequirernente set Jfortjjin 36 CFR Part 60. -

READY, SET, GO! Montana Your Personal Wildland Fire Action Guide

READY, SET, GO! Montana Your Personal Wildland Fire Action Guide READY, SET, GO! Montana Wildland Fire Action Guide Saving Lives and Property through Advanced Planning ire season is now a year-round reality in many areas, requiring firefighters and residents to be on heightened alert for the threat of F wildland fire. This plan is designed to help you get ready, get set, and INSIDE go when a wildland fire approaches. Civilian deaths occur because people wait too long to leave their home. Each year, wildland fires consume hundreds of homes in the Wildland-Urban Living in the Wildland-Urban Interface 3 Interface (WUI). Studies show that as many as 80 percent of the homes lost to wildland fires could have been saved if their owners had only followed a few simple fire-safe practices. Give Your Home a Chance 4 Montana wildland firefighting agencies and your local fire department take every precaution to help protect you and your property from wildland fire. Making a Hardened Home 5 However, the reality is that in a major wildland fire event, there will simply not be enough fire resources or firefighters to defend every home. Successfully preparing for a wildland fire enables you to take personal Tour a Wildland Fire Ready Home 6-7 responsibility for protecting yourself, your family and your property. In this Ready, Set, Go! Action Guide, our goal is to provide you with the tips and tools you need to prepare for a wildland fire threat, to have situational awareness Ready – Preparing for the Fire Threat 8 when a fire starts, and to leave early when a wildland fire threatens, even if you have not received a warning. -

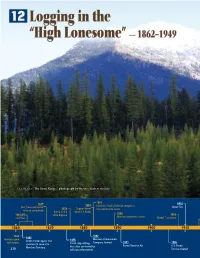

Chapter 12 Review

FIGURE 12.1: “The Swan Range,” photograph by Donnie Sexton, no date 1883 1910 1869 1883 First transcontinental Northern Pacifi c Railroad completes Great Fire 1876 Copper boom transcontinental route railroad completed begins in Butte Battle of the 1889 1861–65 Little Bighorn 1908 Civil War Montana becomes a state Model T invented 1860 1870 1880 1890 1900 1910 1862 1882 1862 Montana gold Montana Improvement Anton Holter opens fi rst 1875 rush begins Salish stop setting Company formed 1891 1905 commercial sawmill in Forest Reserve Act U.S. Forest Montana Territory fi res after confrontation 230 with law enforcement Service created READ TO FIND OUT: n How American Indians traditionally used fire n Who controlled Montana’s timber industry n What it was like to work as a lumberjack n When and why fire policy changed The Big Picture For thousands of years people have used forests to fill many different needs. Montana’s forestlands support our economy, our communities, our homes, and our lives. Forests have always been important to life in Montana. Have you ever sat under a tall pine tree, looked up at its branches sweeping the sky, and wondered what was happen- ing when that tree first sprouted? Some trees in Montana are 300 or 400 years old—the oldest living creatures in the state. They rooted before horses came to the Plains. Think of all that has happened within their life spans. Trees and forests are a big part of life in Montana. They support our economy, employ our people, build our homes, protect our rivers, provide habitat for wildlife, influence poli- tics, and give us beautiful places to play and be quiet. -

MONTANA 2018 Vacation & Relocation Guide

HelenaMONTANA 2018 Vacation & Relocation Guide We≥ve got A Publication of the Helena Area Chamber of Commerce and The Convention & Visitors Bureau this! We will search for your new home, while you spend more time at the lake. There’s a level of knowledge our Helena real estate agents offer that goes beyond what’s on the paper – it’s this insight that leaves you confident in your decision to buy or sell. Visit us at bhhsmt.com Look for our new downtown office at: 50 S Park Avenue Helena, MT 59601 406.437.9493 A member of the franchise system BHH Affiliates, LLC. Equal Housing Opportunity. An Assisted Living & Memory Care community providing a Expect more! continuum of care for our friends, family & neighbors. NOW OPEN! 406.502.1001 3207 Colonial Dr, Helena | edgewoodseniorliving.com 2005, 2007, & 2016 People’s Choice Award Winner Sysum HELENA I 406-495-1195 I SYSUMHOME.COM Construction 2018 HELENA GUIDE Contents Landmark & Attractions and Sports & Recreation Map 6 Welcome to Helena, Attractions 8 Fun & Excitement 14 Montana’s capital city. Arts & Entertainment 18 The 2018 Official Guide to Helena brings you the best ideas for enjoying the Queen City - from Shopping 22 exploring and playing to living and working. Dining Guide 24 Sports & Recreation 28 We≥ve got Day Trips 34 A Great Place to Live 38 this! A Great Place to Retire 44 Where to Stay 46 ADVERTISING Kelly Hanson EDITORIAL Cathy Burwell Mike Mergenthaler Alana Cunningham PHOTOS Convention & Visitors Bureau Montana Office of Tourism Cover Photo: Mark LaRowe MAGAZINE DESIGN Allegra Marketing 4 Welcome to the beautiful city of Helena! It is my honor and great privilege to welcome you to the capital city of Montana. -

Appendix E: Sample Burn Plan Refuge Or Station: San Francisco Bay NWR Complex Unit

Appendix E: Sample Burn Plan Refuge or Station: San Francisco Bay NWR Complex Unit : Antioch Dunes NWR 11646 Date: Prepared By: Date: Roger P. Wong Prescribed Fire Burn Boss Reviewed By: Date: ADR Assistant Refuge Manager The approved Prescribed Fire Plan constitutes the authority to burn, pending approval of Section 7 Consultations, Environmental Assessments, or other required documents. No one has the authority to burn without an approved plan or in a manner not in compliance with the approved plan. Prescribed burning conditions established in the plan are firm limits. Actions taken in compliance with the approved Prescribed Fire Plan will be fully supported, but personnel will be held accountable for actions taken which are not in compliance with the approved plan. Approved By: Date: Margaret Kolar Project Leader San Francisco Bay/Don Edwards NWR 85 PRESCRIBED FIRE PLAN Refuge: San Francisco Bay NWR Complex Refuge Burn Number: Sub Station: Antioch Dunes NWR Fire Number: Name of Areas: Stamm Unit Total Acres To Be Burned: 11 acres divided into 2 units to be burned over one day Legal Description: Stamm Unit T.2N; R.2E, Section 18 Lat. 38 01', Long. 121 48' Is a Section 7 Consultation being forwarded to Fish and Wildlife Enhancement for review? Yes No (circle). Biological Opinion dated June 11, 1997 (Page 2 of this PFP should be a refuge base map showing the location of the burn on Fish and Wildlife Service land.) The Prescribed Fire Burn Boss/Specialist must participate in the development of this plan. I. GENERAL DESCRIPTION OF BURN UNIT Physical Features and Vegetation Cover Types Burn Unit 1B -- Stamm Unit - Hardpan (4 acres): Predominantly annual grasses interspersed with YST and bush lupin “skeletons” from previous year’s prescribed burn. -

Stardigio Program

スターデジオ チャンネル:446 洋楽最新ヒット 放送日:2020/12/14~2020/12/20 「番組案内 (4時間サイクル)」 開始時間:4:00~/8:00~/12:00~/16:00~/20:00~/24:00~ 楽曲タイトル 演奏者名 ■洋楽最新ヒット HOLY Justin Bieber feat. Chance The Rapper I Hope GABBY BARRETT LIFE GOES ON BTS POSITIONS Ariana Grande LEVITATING DUA LIPA feat. DABABY GO CRAZY CHRIS BROWN & YOUNG THUG More Than My Hometown Morgan Wallen Dakiti Bad Bunny & Jhay Cortez Mood 24kGoldn feat. Iann Dior WAP [Lyrics!] CARDI B feat. Megan Thee Stallion MONSTER SHAWN MENDES & JUSTIN BIEBER THEREFORE I AM BILLIE EILISH Lemonade Internet Money feat. Gunna, Don Toliver, NAV KINGS & QUEENS Ava Max BLINDING LIGHTS The Weeknd SAVAGE LOVE (Laxed-Siren Beat) JAWSH 685×Jason Derulo BEFORE YOU GO Lewis Capaldi FOR THE NIGHT Pop Smoke feat. Lil Baby & Dababy BE LIKE THAT Kane Brown feat. Swae Lee & Khalid BANG! AJR All I Want For Christmas Is You (恋人たちのクリスマス) MARIAH CAREY LONELY Justin Bieber & Benny Blanco WATERMELON SUGAR HARRY STYLES LAUGH NOW CRY LATER DRAKE feat. LIL DURK Love You Like I Used To RUSSELL DICKERSON Starting Over Chris Stapleton 7 SUMMERS Morgan Wallen DIAMONDS SAM SMITH FOREVER AFTER ALL LUKE COMBS BETTER TOGETHER LUKE COMBS WHATS POPPIN Jack Harlow ROCKSTAR DABABY feat. RODDY RICCH SAID SUM Moneybagg Yo ONE BEER HARDY feat. Lauren Alaina, Devin Dawson DYNAMITE BTS HAWAI [Remix] Maluma & The Weeknd DON'T STOP Megan Thee Stallion feat. Young Thug MR. RIGHT NOW 21 Savage & Metro Boomin feat. Drake LAST CHRISTMAS WHAM! GOLDEN HARRY STYLES HAPPY ANYWHERE BLAKE SHELTON feat. GWEN STEFANI HOLIDAY LIL NAS X 34+35 Ariana Grande PRISONER Miley Cyrus feat. -

Semester to Wrap up on Musical Note

Volume 83 Number 12 Northwestern College, Orange City, IA December 10, 2010 Hays granted Exhibit brings competition, appreciation BY KATE WALLIN NW Student Art Exhibit, which event.” experience. We’re trying too hard to prestigious CONTRIBUTING WRITER opened this week in Dordt’s The joint exhibit is a tradition be meaningful and artsy sometimes. As finals week approaches, Campus Center Art Gallery. The 12 years in the making. Every year, Not to imply that art shouldn’t be acceptance the end of the semester brings exhibit, open daily from 8 a.m. to 10 over 50 pieces of student art are serious, but sometimes we have the always-expectant stress and p.m., offers a wide range of pieces submitted for consideration by a to step back a bit and make fun BY KATI HENG overwhelming schedules. Hours from all mediums and boasts a panel of student jurors. A team of of ourselves or we’ll get too self- OPINION EDITOR in the library, sleepless nights and unique atmosphere crafted by three NW jurors reviewed Dordt’s absorbed; therefore, octopus.” Senior Greta Hays has been excessive amounts of caffeinated students for students. submissions, while a group from Drawing pieces from different selected for a prestigious arts courage are reason enough to make Professor Rein Vanderhill said, Dordt selected NW’s contributions mediums, the show includes management internship at the us consider getting away, if only for “The students are totally on their to the show. paintings, drawings, mixed Kennedy Center in Washington, a short while. own when they make the selections “The pieces I entered were the media, printmaking, photography, D.C. -

The Complete Poetry of James Hearst

The Complete Poetry of James Hearst THE COMPLETE POETRY OF JAMES HEARST Edited by Scott Cawelti Foreword by Nancy Price university of iowa press iowa city University of Iowa Press, Iowa City 52242 Copyright ᭧ 2001 by the University of Iowa Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Design by Sara T. Sauers http://www.uiowa.edu/ϳuipress No part of this book may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the publisher. All reasonable steps have been taken to contact copyright holders of material used in this book. The publisher would be pleased to make suitable arrangements with any whom it has not been possible to reach. The publication of this book was generously supported by the University of Iowa Foundation, the College of Humanities and Fine Arts at the University of Northern Iowa, Dr. and Mrs. James McCutcheon, Norman Swanson, and the family of Dr. Robert J. Ward. Permission to print James Hearst’s poetry has been granted by the University of Northern Iowa Foundation, which owns the copyrights to Hearst’s work. Art on page iii by Gary Kelley Printed on acid-free paper Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Hearst, James, 1900–1983. [Poems] The complete poetry of James Hearst / edited by Scott Cawelti; foreword by Nancy Price. p. cm. Includes index. isbn 0-87745-756-5 (cloth), isbn 0-87745-757-3 (pbk.) I. Cawelti, G. Scott. II. Title. ps3515.e146 a17 2001 811Ј.52—dc21 00-066997 01 02 03 04 05 c 54321 01 02 03 04 05 p 54321 CONTENTS An Introduction to James Hearst by Nancy Price xxix Editor’s Preface xxxiii A journeyman takes what the journey will bring.