Food Delivery Platforms: Will They Eat the Restaurant Industry's Lunch?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Food Delivery Brands Head-To-Head the Ordering Operation

FOOD DELIVERY BRANDS HEAD-TO-HEAD THE ORDERING OPERATION Market context: The UAE has a well-established tradition of getting everything delivered to your doorstep or to your car at the curb. So in some ways, the explosion of food delivery brands seems almost natural. But with Foodora’s recent exit from the UAE, the acquisition of Talabat by Rocket Internet, and the acquisition of Foodonclick and 24h by FoodPanda, it seemed the time was ripe to put the food delivery brands to the test. Our challenge: We compared six food delivery brands in Dubai to find the most rewarding, hassle-free ordering experience. Our approach: To evaluate the complete customer experience, we created a thorough checklist covering every facet of the service – from signing up, creating accounts, and setting up delivery addresses to testing the mobile functionality. As a control sample, we first ordered from the same restaurant (Maple Leaf, an office favorite) using all six services to get a taste for how each brand handled the same order. Then we repeated the exercise, this time ordering from different restaurants to assess the ease of discovering new places and customizing orders. To control for other variables, we placed all our orders on weekdays at 1pm. THE JUDGING PANEL 2 THE COMPETITIVE SET UAE LAUNCH OTHER MARKETS SERVED 2011 Middle East, Europe 2015 12 countries, including Hong Kong, the UK, Germany 2011 UAE only 2010 Turkey, Lebanon, Qatar 2012 GCC, including Bahrain, Kuwait, Qatar, Saudi Arabia 2015 17 countries, including India, the USA, the UK THE REVIEW CRITERIA: • Attraction: Looks at the overall design, tone of voice, community engagement, and branding. -

Davivienda Arrives at Super App Rappi to Revolutionize the Way Money Is Managed

Davivienda arrives at Super App Rappi to revolutionize the way money is managed: • With an innovative product offering, a bank and a delivery and e-commerce platform join experiences and trust to make payments, purchases, transfers, and to save and handle money. • Rappi is a SuperAPP that innovatively integrates everything from supermarket shopping to transportation solutions; now, introducing money management; all in one place. • RappiPay Davivienda is designed for the Pay Generation: a generation we all belong to, because we live experiences and manage finances from our mobile phones. Bogota, May 2019. All the innovation of Davivienda and Latin America´s Super App Rappi come together to bring Colombians new experiences and possibilities to make purchases and manage money easily and reliably. From now on, actions such as making purchases at Rappi, paying for a hamburger by scanning a QR code, transferring money to a friend to pay off a debt, withdrawing cash at an ATM using a mobile phone or making local and international purchases with the Rappi Visa debit card will be possible from one place: RappiPay Davivienda. Beyond being an innovative payment model, Rappi Pay Davivienda, transforms the path towards the future opening of payment ecosystems between Fintechs and Banks. This alliance enhances digital and secure payments in Colombia, lowers access and transaction costs, reduces the use of cash, and strengthens businesses and entrepreneurs in the country, both in e-commerce and in conventional stores, thanks to its features and benefits. Joining RappiPay Davivienda does not require paperwork or being a Davivienda customer. The process is as simple as downloading Rappi, activating RappiPay Davivienda on the App, and adding money either through another RappiPay Davivienda, by electronic transfer from any bank, through an authorized agent or at any Davivienda branch. -

Track Screen Ads on Swiggy Overview of Swiggy

Track Screen Ads on Swiggy Overview of Swiggy Swiggy ( www.swiggy.com) is an online food ordering and delivery platform that allows customers to order food from restaurants near them. Presence in ~ 12 - 14 MM transacting 200+ cities pan India users visiting every month 40 MM orders / month pan ~50%* market share in India food delivery Double digit MOM growth PAN India 100K+ transacting restos ~25% on board conversion rate Top 7 cities of Swiggy * Market Share nos. are as per reports shared by RedSeer Consulting Why customers love Swiggy ? Swiggy’s Growth Story Swiggy ( www.swiggy.com) has grown phenomenally over the past 24 months (clocking ~11X growth). With expansions in new geographies & more verticals, Swiggy’s growth story is poised to become stronger ~11X Growth Reach the audience that matters to you, at scale Monthly transacting base of ~10 mn users High stickiness on the platform, with an average ordering frequency of 3+ per user Young (18-44MF) Urban Digitally active & Engaged (Top 50 cities) Transacting users Users Food & Beverage context Hyperlocality Strategic post-transaction video ad units to ensure higher engagement • Non-skip, Autoplay, Clickable video unit • Average Monthly Reach: 10mn+ • Average Monthly impressions on track screen: 30mn+ • Average completion rate: 70% • Avg. CTR: 0.2- 0.4% Video unit in Landscape Mode Video unit in Portrait Mode Reinforce brand message or drive performance with display ad units • Display units in standalone as well as carousal format to create the full brand story • Average Monthly Reach: 10mn+ • Average Monthly impressions on track screen: 30mn+ • Avg. CTR on Display: 0.3 – 0.5% Brands across categories have seen results with Swiggy’s in-app ad units BFSI E-commerce Auto / OTT (Customer Acquisition) (Sale / Offer Awareness) (Launch Amplification) Thank You Annexure 1: Display Unit specifications • Card dimensions: 1280 x 1000px • No CTA button on the creative • Carousal Title: Upto 30 characters (incl. -

Chinese Investments in India

CHINESE INVESTMENTS IN INDIA Amit Bhandari, Fellow, Energy & Environment Studies Programme, Blaise Fernandes, Board Member, Gateway House and President & CEO, The Indian Music Industry & Aashna Agarwal, Former Researcher Report No. 3, Map No. 10 | February 2020 Disclaimer: While every effort has been made to ensure that data is accurate and reliable, these maps are conceptual and in no way claim to reflect geopolitical boundaries that may be disputed. Gateway House is not liable for any loss or damage whatsoever arising out of, or in connection with the use of, or reliance on any of the information from these maps. Published by Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations 3rd floor, Cecil Court, M.K.Bhushan Marg, Next to Regal Cinema, Colaba, Mumbai 400 039 T: +91 22 22023371 E: [email protected] W: www.gatewayhouse.in Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations is a foreign policy think tank in Mumbai, India, established to engage India’s leading corporations and individuals in debate and scholarship on India’s foreign policy and the nation’s role in global affairs. Gateway House is independent, non-partisan and membership-based. Editors: Manjeet Kripalani & Nandini Bhaskaran Cover Design & Map Visualisation: Debarpan Das Layout: Debarpan Das All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without prior written permission of the publisher. © Copyright 2020, Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. Methodology Our preliminary research indicated that the focus of Chinese investments in India is in the start-up space. -

Response: Just Eat Takeaway.Com N. V

NON- CONFIDENTIAL JUST EAT TAKEAWAY.COM Submission to the CMA in response to its request for views on its Provisional Findings in relation to the Amazon/Deliveroo merger inquiry 1 INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND 1. In line with the Notice of provisional findings made under Rule 11.3 of the Competition and Markets Authority ("CMA") Rules of Procedure published on the CMA website, Just Eat Takeaway.com N.V. ("JETA") submits its views on the provisional findings of the CMA dated 16 April 2020 (the "Provisional Findings") regarding the anticipated acquisition by Amazon.com BV Investment Holding LLC, a wholly-owned subsidiary of Amazon.com, Inc. ("Amazon") of certain rights and minority shareholding of Roofoods Ltd ("Deliveroo") (the "Transaction"). 2. In the Provisional Findings, the CMA has concluded that the Transaction would not be expected to result in a substantial lessening of competition ("SLC") in either the market for online restaurant platforms or the market for online convenience groceries ("OCG")1 on the basis that, as a result of the Coronavirus ("COVID-19") crisis, Deliveroo is likely to exit the market unless it receives the additional funding available through the Transaction. The CMA has also provisionally found that no less anti-competitive investors were available. 3. JETA considers that this is an unprecedented decision by the CMA and questions whether it is appropriate in the current market circumstances. In its Phase 1 Decision, dated 11 December 20192, the CMA found that the Transaction gives rise to a realistic prospect of an SLC as a result of horizontal effects in the supply of food platforms and OCG in the UK. -

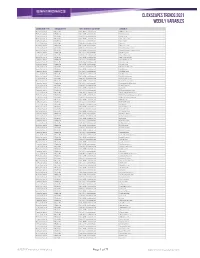

Clickscapes Trends 2021 Weekly Variables

ClickScapes Trends 2021 Weekly VariableS Connection Type Variable Type Tier 1 Interest Category Variable Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment 1075koolfm.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment 8tracks.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment 9gag.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment abs-cbn.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment aetv.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment ago.ca Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment allmusic.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment amazonvideo.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment amphitheatrecogeco.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment ancestry.ca Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment ancestry.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment applemusic.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment archambault.ca Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment archive.org Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment artnet.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment atomtickets.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment audible.ca Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment audible.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment audiobooks.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment audioboom.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment bandcamp.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment bandsintown.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment barnesandnoble.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment bellmedia.ca Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment bgr.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment bibliocommons.com -

List of Brands

Global Consumer 2019 List of Brands Table of Contents 1. Digital music 2 2. Video-on-Demand 4 3. Video game stores 7 4. Digital video games shops 11 5. Video game streaming services 13 6. Book stores 15 7. eBook shops 19 8. Daily newspapers 22 9. Online newspapers 26 10. Magazines & weekly newspapers 30 11. Online magazines 34 12. Smartphones 38 13. Mobile carriers 39 14. Internet providers 42 15. Cable & satellite TV provider 46 16. Refrigerators 49 17. Washing machines 51 18. TVs 53 19. Speakers 55 20. Headphones 57 21. Laptops 59 22. Tablets 61 23. Desktop PC 63 24. Smart home 65 25. Smart speaker 67 26. Wearables 68 27. Fitness and health apps 70 28. Messenger services 73 29. Social networks 75 30. eCommerce 77 31. Search Engines 81 32. Online hotels & accommodation 82 33. Online flight portals 85 34. Airlines 88 35. Online package holiday portals 91 36. Online car rental provider 94 37. Online car sharing 96 38. Online ride sharing 98 39. Grocery stores 100 40. Banks 104 41. Online payment 108 42. Mobile payment 111 43. Liability insurance 114 44. Online dating services 117 45. Online event ticket provider 119 46. Food & restaurant delivery 122 47. Grocery delivery 125 48. Car Makes 129 Statista GmbH Johannes-Brahms-Platz 1 20355 Hamburg Tel. +49 40 2848 41 0 Fax +49 40 2848 41 999 [email protected] www.statista.com Steuernummer: 48/760/00518 Amtsgericht Köln: HRB 87129 Geschäftsführung: Dr. Friedrich Schwandt, Tim Kröger Commerzbank AG IBAN: DE60 2004 0000 0631 5915 00 BIC: COBADEFFXXX Umsatzsteuer-ID: DE 258551386 1. -

Pre-Feasibility Analysis for the Creation of a Delivery Company in a Context of Great Competition

PRE-FEASIBILITY ANALYSIS FOR THE CREATION OF A DELIVERY COMPANY IN A CONTEXT OF GREAT COMPETITION Alberto Barrera Valdeolivas, s265308 11 DICEMBRE 2020 AMAZON CORPORATE Relatore: Maurizio Schenone Credits To Alice, the light of my life, the one that has given me so many good moments and has helped me so much in the last 3 years. To my family: my parents, my sister, my grandparents ... they are the greatest thing I have. To my Italian family, who have always shown me to be one more and have welcomed me from the first moment I arrived To my roommates in Turin: Pol, Sergio, Barbany and Marc. They gave me two of the best years of my life and unforgettable moments. Ai miei fratelli Stenis, Matteo e le mie grandi amiche Chiri, Cecilia and Giulia. To Kobe, the very new member of the family, we are so proud and happy to have you in our lives. 1 Index 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................ 4 1.1 Origin and Motivation ...................................................................................... 4 1.2 Aims and Scope ................................................................................................ 5 1.3 Structure of the document ................................................................................ 6 2 Context ........................................................................................................................ 7 2.1 Actual Delivery System .................................................................................. -

Online Transportation Price War: Indonesian Style

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Klaipeda University Open Journal Systems SAKTI HENDRA PRAMUDYA ONLINE TRANSPORTATION PRICE WAR: INDONESIAN STYLE ONLINE TRANSPORTATION PRICE WAR: INDONESIAN STYLE Sakti Hendra Pramudya1 Universitas Bina Nusantara (Indonesia), University of Pécs (Hungary) ABStrAct thanks to the brilliant innovation of the expanding online transportation companies, the Indonesian people are able to obtain an affor- dable means of transportation. this three major ride-sharing companies (Go-Jek, Grab, and Uber) provide services which not only limited to transportation service but also providing services for food delivery, courier service, and even shopping assistance by utili- zing gigantic armada of motorbikes and cars which owned by their ‘driver partners’. these companies are competing to gain market share by implementing the same strategy which is offering the lowest price. this paper would discuss the Indonesian online trans- portation price war by using price comparison analysis between three companies. the analysis revealed that Uber was the winner of the price war, however, their ‘lowest price strategy’ would lead to their downfall not only in Indonesia but in all of South East Asia. KEYWOrDS: online transportation companies, price war, Indonesia. JEL cODES: D40, O18, O33 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15181/rfds.v29i3.2000 Introduction the idea of ride-hailing was unfamiliar to Indonesian people. Before the inception (and followed by the large adoption) of smartphone applications in Indonesia, the market of transportation service was to- tally different. the majority of middle to high income Indonesian urban dwellers at that time was using the conventional taxi as their second option of transportation after their personal car or motorbike. -

Glovo Scales and Delivers with Makemereach 60% 24%

Glovo scales and delivers with MakeMeReach CASE STUDY Glovo delivers any local product to your door in an average of 30 mins. From electronics, to food, to flowers, Glovo fills the gap between offline and online commerce - on demand and on mobile. Scale quickly In Spain, Glovo has relied on the MakeMeReach solution as a crucial pillar in their scale-up strategy throughout the spanish-speaking world. In September 2017, after roughly two-and-a-half years in business, Glovo decided it was time to scale quickly. In just over a year they’ve added more than 100 cities, and are now active in 22 countries worldwide. Added to that, they’ve multiplied their number or orders delivered by 10 - from 1 million in September 2017, to over 10 million in late 2018. Targeting approach To achieve this kind of growth, Glovo have had to be smart about how they establish their activity in new cities. Their business model is such that they are not only interested in acquiring new users of the service, but also new delivery people (called ‘Glovers’) in each new city. To get both users and Glovers on board, and ensure each new location started off with a bang, Glovo followed a two-stage targeting approach for their Facebook and Instagram advertising campaigns: In the first stage, focusing on individual suburbs at a time, Glovo used broad targeting to Then, in the second reach males and females stage, they built on this aged 20-54 years old. initial audience with lookalikes and additional interest-based groups. -

Food and Tech August 13

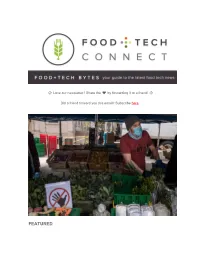

⚡️ Love our newsletter? Share the ♥️ by forwarding it to a friend! ⚡️ Did a friend forward you this email? Subscribe here. FEATURED Small Farmers Left Behind in Covid Relief, Hospitality Industry Unemployment Remains at Depression-Era Levels + More Our round-up of this week's most popular business, tech, investment and policy news. Pathways to Equity, Diversity + Inclusion: Hiring Resource - Oyster Sunday This Equity, Diversity + Inclusion Hiring Resource aims to help operators to ensure their tables are filled with the best, and most equal representation of talent possible – from drafting job descriptions to onboarding new employees. 5 Steps to Move Your Food, Beverage or Hospitality Business to Equity Jomaree Pinkard, co-founder and CEO of Hella Cocktail Co, outlines concrete steps businesses and investors can take to foster equity in the food, beverage and hospitality industries. Food & Ag Anti-Racism Resources + Black Food & Farm Businesses to Support We've compiled a list of resources to learn about systemic racism in the food and agriculture industries. We also highlight Black food and farm businesses and organizations to support. CPG China Says Frozen Chicken Wings from Brazil Test Positive for Virus - Bloomberg The positive sample appears to have been taken from the surface of the meat, while previously reported positive cases from other Chinese cities have been from the surface of packaging on imported seafood. Upcycled Molecular Coffee Startup Atomo Raises $9m Seed Funding - AgFunder S2G Ventures and Horizons Ventures co-led the round. Funding will go towards bringing the product to market. Diseased Chicken for Dinner? The USDA Is Considering It - Bloomberg A proposed new rule would allow poultry plants to process diseased chickens. -

FUTURE of FOOD a Lighthouse for Future Living, Today Context + People and Market Insights + Emerging Innovations

FUTURE OF FOOD A Lighthouse for future living, today Context + people and market insights + emerging innovations Home FUTURE OF FOOD | 01 FOREWORD: CREATING THE FUTURE WE WANT If we are to create a world in which 9 billion to spend. That is the reality of the world today. people live well within planetary boundaries, People don’t tend to aspire to less. “ WBCSD is committed to creating a then we need to understand why we live sustainable world – one where 9 billion Nonetheless, we believe that we can work the way we do today. We must understand people can live well, within planetary within this reality – that there are huge the world as it is, if we are to create a more boundaries. This won’t be achieved opportunities available, for business all over sustainable future. through technology alone – it is going the world, and for sustainable development, The cliché is true: we live in a fast-changing in designing solutions for the world as it is. to involve changing the way we live. And world. Globally, people are both choosing, and that’s a good thing – human history is an This “Future of” series from WBCSD aims to having, to adapt their lifestyles accordingly. endless journey of change for the better. provide a perspective that helps to uncover While no-one wants to live unsustainably, and Forward-looking companies are exploring these opportunities. We have done this by many would like to live more sustainably, living how we can make sustainable living looking at the way people need and want to a sustainable lifestyle isn’t a priority for most both possible and desirable, creating live around the world today, before imagining people around the world.