Addis Ababa University School of Graduate Studies Christian Radio

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Streams of Civilization: Volume 2

Copyright © 2017 Christian Liberty Press i Streams Two 3e TEXT.indb 1 8/7/17 1:24 PM ii Streams of Civilization Volume Two Streams of Civilization, Volume Two Original Authors: Robert G. Clouse and Richard V. Pierard Original copyright © 1980 Mott Media Copyright to the first edition transferred to Christian Liberty Press in 1995 Streams of Civilization, Volume Two, Third Edition Copyright © 2017, 1995 Christian Liberty Press All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, without written permission from the publisher. Brief quota- tions embodied in critical articles or reviews are permitted. Christian Liberty Press 502 West Euclid Avenue Arlington Heights, Illinois 60004-5402 www.christianlibertypress.com Copyright © 2017 Christian Liberty Press Revised and Updated: Garry J. Moes Editors: Eric D. Bristley, Lars R. Johnson, and Michael J. McHugh Reviewers: Dr. Marcus McArthur and Paul Kostelny Layout: Edward J. Shewan Editing: Edward J. Shewan and Eric L. Pfeiffelman Copyediting: Diane C. Olson Cover and Text Design: Bob Fine Graphics: Bob Fine, Edward J. Shewan, and Lars Johnson ISBN 978-1-629820-53-8 (print) 978-1-629820-56-9 (e-Book PDF) Printed in the United States of America Streams Two 3e TEXT.indb 2 8/7/17 1:24 PM iii Contents Foreword ................................................................................1 Introduction ...........................................................................9 Chapter 1 European Exploration and Its Motives -

Parish Magazine of Christ Church Stone

Parish Magazine of Christ Church Stone PARISH DIRECTORY SUNDAY SERVICES Details of our services are given on pages 2 and 3. Young people’s activities take place in the Centre at 9.15 am THE PARISH TEAM Vicar Paul Kingman 812669 The Vicarage, Bromfield Court Parish Administrator Clare Nash (Office) 811990 Electoral Roll Officer Irene Gassor 814871 Parish Office Christ Church Centre, Christ Church Way, Stone, Staffs ST15 8ZB Email [email protected] Youth Worker Thomas Nash 286551 Deaconess (Retired) Ann Butler 818160 Readers David Bell 815775 John Butterworth 817465 Margaret Massey 813403 David Rowlands 816713 Michael Thompson 813712 Cecilia Wilding 817987 Music Co-ordinators Peter Mason 815854 Jeff Challinor 819665 Wardens Phil Tunstall 817028 David Rowlands 816713 Deputy Wardens Shirley Hallam, Arthur Foulkes Prayer Request List Barbara Thornicroft 818700 CHRIST CHURCH CENTRE Booking Secretary Shelagh Sanders (Office) 811990 (Home) 760602 CHURCH SCHOOLS Christ Church C.E.(Controlled) First School, Northesk Street. Head: Mrs Lynne Croxall B.Ed.(Hons) 354125 Christ Church C.E.(Aided) Middle School, Old Road Head: C. Waghorn B.Ed(Hons),DPSE,ACP,FRSA 354047 1 In This Issue Diary for May 2 Elected 4 Liars, Evil Brutes and Lazy Gluttons 5 What a Liberty! 5 Easter Flowers (Thank You) 5 MEGAQUEST Holiday Club 6 Please get your Christ Church Middle School 7 contributions for the June St John the Evangelist Church, Oulton 8 magazine to us Radiance, A feast of Christian Spirituality 9 by 15th May Feba Radio 10 Wedding of Rachel Morray and Paul Swin- 11 son Michelle Parry 12 A Thank You for prayers 12 Mini Keswick heads for a First in Lichfield 13 Little Fishes- Friday Toddler Group 13 PCC News 15 Roads for Prayer 16 From the Registers 16 Cover Story: Jerry Cooper drew lots of wonderful pictures for this magazine, all of them buildings in our parish. -

Locally Generated Printed Materials in Agriculture: Experience from Uganda and Ghana

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Research Papers in Economics Locally Generated Printed Materials in Agriculture: Experience from Uganda and Ghana - Education Research Paper No. 31, 1999, 132 p. Table of Contents EDUCATION RESEARCH Isabel Carter July 1999 Serial No. 31 ISBN: 1 86192 079 2 Department For International Development Table of Contents List of acronyms Acknowledgements Other DFID Education Studies also Available List of Other DFID Education Papers Available in this Series Department for International Development Education Papers 1. Executive summary 1.1 Background 1.2 Results 1.3 Conclusions 1.4 Recommendations 2. Background to research 2.1 Origin of research 2.2 Focus of research 2.3 Key definitions 3. Theoretical issues concerning information flow among grassroots farmers 3.1 Policies influencing the provision of information services for farmers 3.2 Farmer access to information provision 3.3 Farmer-to-farmer sharing of information 3.4 Definition of locally generated materials 3.5 Summary: Knowledge is power 4. Methodology 4.1 Research questions 4.2 Factors influencing the choice of methodologies used 4.3 Phase I: Postal survey 4.4 Phase II: In-depth research with farmer groups 4.5 Research techniques for in-depth research 4.6 Phase III: Regional overview of organisations sharing agricultural information 4.7 Data analysis 5. Phase I: The findings of the postal survey 5.1 Analysis of survey respondents 5.2 Formation and aims of groups 5.3 Socio-economic status of target communities 5.4 Sharing of Information 5.5 Access to sources of information 6. -

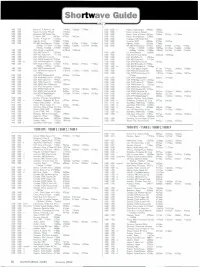

Shortwave Guide

Shortwave Guide 400 1500 Romania, R Romania Intl 11940eu I5365eu 17790eu 500 1 600 d Nigeria, Rodio/Logos 4990do 7287:Vas 400 1500 Russia, University Network 17765os 5W 1 600 Russia, University Network 400 1500 Singapore, SBC Radio One 6150do 5C/0 1 600 Russia, Voice of Russo 6205as 7260na 7315as 157350m 400 1500 Sr Lonka, SLBC 6005os 9770as 15425as 500 1 600 Russo, World Beacon 15340eu 400 1500 Taiwan,R Taipei Intl 15265as 500 1 600 Singapore, SBC Radio One 6150do 400 1500 Uganda, Radio 5026do 7196do 5W 1 600 Sr Lanka, SLBC 6005as 9770as 15425os 400 1500 UK, BBC World Service6135as 6190o1 6195os 9740as 1194001 500 1 600 Ugondo, Radio 5026do 7196do 12095eu 15190om 15310as I 5485eu 15565eu 15575meI 7640eu 500 1 600 UK, BBC World Service 5975os 6135as 6190of 6195as 9410eu 17700os 17830o1 21470of 21660of 9740os 11860x1 I 1940of I2095eu 15190am15400of 15420o1 400 500 USA, Armed Forces Rodio 6458usb I 2689usb I 5485eu 15565eu 17700os I 7830of 21470of 21490of 21660af 400 500 USA, KAIJ Dallas TX 1381 5vo UK, World Beacon I 5340eu 400 500 USA, KJES Vado NM 11715na USA, Armed Forces Radio 6458usb I 2689usb 400 500 USA, KTBN Salt Lk City UT 7510no USA, KAIJ Dallas TX 13815vo 400 500 USA, KWHR Naolehu HI 9930as USA, KJES Vodo NM II 715no 400 500 os USA, KWHR Noolehu HI11 565po USA, KTBN Salt Lk City UT 751 Ono 400 500 USA, Voice of Americo 6110as 7125as 9645as 9760os II 705as USA, KWHR Naalehu HI 9930as 15205as 15395as 15425as as USA, KWHR Noolehu HI 11565pa 400 500 USA, mica Monticello ME I 7495no USA, VOA Special English 6110as 9760os 12040as -

Prayer Focus July -October2016 1 2 These Broadcasts Daily

Prayer Focus July - October 2016 Making followers of Christ through media 1 FEBC China – Liangyou Theological Seminary (continue) JULY Fri 1 – Praise God for the dedicated students Liangyou Theological Seminary (LTS) website. from 20 provinces in China who visited the Hong The download rate of files and additional arti- Kong studios for intensive study camps over the cles, as well as the hit rate for discussions and last few years. the ‘Prayer Room’ have increased dramatically with the new LTS website, attracting millions of Sat 2 – Thank God for the highly interactive downloads and hits per year. FEBC Hong Kong – Radio Liangyou and Radio Yiyou Sun 3 – WEEKLY SUMMARY: FEBC Hong Tue 5 – More than 50 programs are produced Kong is the production center for our Chinese and aired by the staff of these two stations. and other minority languages’ broadcasted pro- Some of the popular programs include Liangyou grams. They coordinate the daily production Theological Seminary, Radio Counselling Corner, of 33.5 hours of programs produced by sever- and Seasons of Life. Pray that God will bless the al FEBC studios in Singapore, Taipei, La Mirada, producers and broadcasters of these programs. Vancouver, Toronto and Hong Kong. More than 32 hours of these programs are available on the Wed 6 – Radio Liangyou and Radio Yiyou re- internet. FEBC Hong Kong’s staff regularly vis- ceive about 78 000 listener responses annually! its their listeners and they also distribute radios, Praise God for this great response rate. Also pray CD’s, and other materials. Join us in prayer this that more people will listen and respond to these week for two of FEBC Hong Kong’s radio sta- stations. -

March - June 2019

PRAYER FOCUS March - June 2019 1 FEBC Japan (Continued) MARCH Sat 2 – In a country like Japan where there Fri 1 – A listener from Japan struggled with are very few Christians, there is a great need an eating disorder, but once she started lis- for the gospel. Pray that Pastor Sekino, who tening to FEBC’s broadcasts, she gave her life is one of FEBC’s broadcasters, will capture to Jesus and is completely set free. Praise the hearts of the youth and inspire them to the Lord for his goodness! draw near to Christ. FEBC Australia Sun 3 – WEEKLY SUMMARY: FEBC Aus- Thu 7 – The team is in need of godly, gifted tralia supports 16 FEBC & FEBA ministry fields and competent people to join their mission and also the shortwave broadcasts to ethnic team in order to expand the work. Please minorities throughout Southeast Asia. They pray that those responsible for recruitment also provide thousands of radios & speaker will apply wisdom and discernment when boxes annually for distribution international- choosing candidates. ly. Recently they donated 1000 speaker box- es to FEBA Malawi and a similar amount to Fri 8 – Pray that God will continue to bless FEBC Thailand. They walk in faith and are the Australian people and that out of their fully dependent on God to accomplish FEBC’s abundance they will be inspired to gener- mission to inspire people to follow Jesus. Join ously support the work of God through FEBC us in prayer this week for FEBC Australia. Australia. Mon 4 – FEBC Australia hopes to inspire peo- Sat 9 – Please pray for Director Kevin Keegan ple to support their ministry as they share and his team which is very small with only 2 the power of God through FEBC and FEBA in full time and 3 part-time staff members. -

September 2008 Minreport

individuals and churches have access to a variety of materials in a more timely manner than ever before. In This Issue Methods of design and implementation change, and materials produced for an event are handled more Congregational Support creatively and with greater speed than the year before – Abuse Prevention or the month before! Chaplaincy Ministries For an example of this widespread networking, Disability Concerns check out Abuse Awareness 2008 on the web Dynamic Youth Ministries www.crcna.org/order . Individuals and churches can Faith Alive Christian Resources order a wider array of materials and resources than ever Pastor Church Relations before and most of it available by a click of a button into a Service Link virtual “shopping cart”. Diaconal Ministries CRWRC Partners Worldwide Chaplaincy Ministries Educational Institutions Calvin College Chaplaincy Ministries transcends many boundaries both Mission Organizations outside and within the Christian Reformed Church. Back to God Ministries International Our work takes us beyond the organizations of the Home Missions CRCNA. Not only Calvin Theological Seminary, but other World Missions seminaries, and our colleges are contacted for recruitment. We contact every calling church, every classis, and every employer—civilian and military—for endorsement of chaplains for ministry. Abuse Prevention We are in contact with The American Association of Pastoral Counselors, the Association of Clinical Pastoral The well-worn expression, “It takes a village…” applies to Education, the Association of Professional Chaplains, the the ministry of Abuse Prevention. The ministry relies on a Canadian Association of Pastoral Practice and “village” of volunteers, colleagues and web sites to make Education, and the Council on Collaboration when resources and information available to individuals and to working toward standardization of credentialing our churches. -

1400 Utc Shortwave! 7:00 Am Pdt Frequencies

10:00 AM EDT 1400 UTC SHORTWAVE! 7:00 AM PDT FREQUENCIES 1400-1500 Australia, AF Radio 8743af 10621 af 1400-1500 United Kingdom,BBC London 6190aí 6195as 7180as 9410va 1400-1430 Australia, Radio 7240pa 9560as 9610pa 11695pa 9515na 9740va 11365am 11750as 1400-1500 Australia, Radio 5995pa 11800pa 11865va 11940af 12095va 15070va 1400-1435 mtwhfa Belgium, R Vlaanderen Int 13670na 15310as 15575me 17640va 17705va 1400-1500 vl Canada, CBC N Quebec Svc 9625do 17830af 21470aí 21660aí 1400-1500 Canada, CFCX Montreal 6005do 1400-1500 USA, KJES Mesquite NM 11715na 1400-1500 Canada, CFRX Toronto 6070do 1400-1500 USA, KTBN Salt Lk City UT 7510am 1400-1500 Canada, CFVP Calgary 6030do 1400-1500 USA, Monitor Radio Intl 9355as 1400-1500 Canada, CHNX Halifax 6130áo 1400.1500 USA, VOA Washington DC 6110va 7125va 7215va 9645va 1400-1500 Canada, CKZN St John's 6160do 9760va 15160va 15255va 15395va 1400-1500 Canada, CKZU Vancouver 6160do 15425va 1400-1500 s Canada, RCI Montreal 11955na 17820na 1400-1500 USA, WEWN Birmingham AL 7425na 11875na 1400-1500 China, China Radio Intl 7405na 11815as 1400-1500 irreg USA, WGTG McCaysville GA 7355am 11760am 1400-1500 Costa Rica, R Peace Intl 6200am 9400am 15050am 1400- 1400-1500 USA, WHRI Noblesville IN 6040am 15105am 1400-1500 France, Radio France Intl 7110as 15405as 17560as 17695as 1400-1500 USA, WJCR Upton KY 7490na 13595na 1400-1500 Ecuador, HCJB Quito 12005am 15115am 1400-1500 USA, WRNO New Orleans LA 15420am 1400-1500 India, All India Radio 13732as 15120as 1400-1445 a USA, WVHA Green Bush ME 11695af 1400-1500 Japan, -

Sourcebook with Marie's Help

AIB Global Broadcasting Sourcebook THE WORLDWIDE ELECTRONIC MEDIA DIRECTORY | TV | RADIO | CABLE | SATELLITE | IPTV | MOBILE | 2009-10 EDITION WELCOME | SOURCEBOOK AIB Global WELCOME Broadcasting Sourcebook THE WORLDWIDE ELECTRONIC MEDIA DIRECTORY | TV | RADIO | CABLE | SATELLITE | IPTV | MOBILE | 2009 EDITION In the people-centric world of broadcasting, accurate information is one of the pillars that the industry is built on. Information on the information providers themselves – broadcasters as well as the myriad other delivery platforms – is to a certain extent available in the public domain. But it is disparate, not necessarily correct or complete, and the context is missing. The AIB Global Broadcasting Sourcebook fills this gap by providing an intelligent framework based on expert research. It is a tool that gets you quickly to what you are looking for. This media directory builds on the AIB's heritage of more than 16 years of close involvement in international broadcasting. As the global knowledge The Global Broadcasting MIDDLE EAST/AFRICA network on the international broadcasting Sourcebook is the Richie Ebrahim directory of T +971 4 391 4718 industry, the AIB has over the years international TV and M +971 50 849 0169 developed an extensive contacts database radio broadcasters, E [email protected] together with leading EUROPE and is regarded as a unique centre of cable, satellite, IPTV information on TV, radio and emerging and mobile operators, Emmanuel researched by AIB, the Archambeaud platforms. We are in constant contact -

Adopt-A-People. It Is Difficult to Sustain A

Agricultural Missions Adopt-a-People. It is difficult to sustain a mis- cated and wild species), provision of creative em- sion focus on the billions of people in the world ployment for people, sustenance of strategic or even on the multitudes of languages and cul- stocks of food against poor harvests, and the in- tures in a given country. Adopt-a-people is a mis- tegration with other uses of land for human wel- sion mobilization strategy that helps Christians fare. get connected with a specific group of people Aims of Agricultural Mission. Agricultural who are in spiritual need. It focuses on the goal missionary work aims to present the good news of discipling a particular people group (see PEO- of Jesus Christ in rural areas so that this gospel PLES, PEOPLE GROUPS), and sees the sending of transforms not only individuals and their social missionaries as one of the important means to relationships, but also the way they farm. In fulfill that goal. short, agricultural missions seek to promote liv- Adopt-a-people was conceptualized to help ing and farming to the glory of God. In effect, congregations focus on a specific aspect of the God has provided two means of conveying how GREAT COMMISSION. It facilitates the visualization this should be done—creation and the Bible— of the real needs of other people groups, enables which are perceived through the senses and con- the realization of tangible accomplishments, de- science, and which require the motivation of the velops and sustains involvement, and encourages Holy Spirit to enable us to farm accordingly. -

THE ARRIVAL of RADIO FARDA: INTERNATIONAL BROADCASTING to IRAN at a CROSSROADS by Hansjoerg Biener*

THE ARRIVAL OF RADIO FARDA: INTERNATIONAL BROADCASTING TO IRAN AT A CROSSROADS by Hansjoerg Biener* Abstract: On December 19, 2002, Radio Farda, the new U.S. external service in Persian, officially started regular broadcasts on shortwave, mediumwave and satellite. With the reformatting of existing services into a 24-hour news and entertainment channel, external broadcasting to Iran has recently received more attention. Iran, however, has always been the target area of various international broadcasting services.(1) In its first worldwide press-freedom index published on October 23, 2002, Reporters Without Borders ranked Iran 122nd among 139 countries surveyed.(2) So, the need for independent reporting seems obvious, while some question the need for embedding news and information in a music and entertainment format. This article examines the question in the broader context of international broadcasting to Iran, including clandestine and even religious stations. CLASSIC EXTERNAL resumed operation. The service almost BROADCASTING exclusively drew on native speakers Having been a major political factor some of whom had broadcasting both under Shah Reza Pahlavi and under experience in Iranian radio and Mullah rule, Iran has been a traditional television before 1979. In the 1980s, target area for official external services long before the arrival of e-mail, the both from neighboring countries like Farsi service received several hundred Iraq, Kuwait, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia and letters per week in response to the Turkey, as well as the world’s broadcasts.(3) On October 17, 1996, superpowers. In the framework of Voice of America and Worldnet centralized USSR external broadcasting, launched a weekly, call-in radio and TV Radio Baku of the Soviet Republic simulcast in Farsi, the first regularly Azerbaijan only had a minor role as an recurring program to be produced in full external broadcaster, which did however at the VoA headquarters. -

Seychelles Country Report

SEYCHELLES COUNTRY REPORT For use in Radiology Outreach Initiatives Author Mohammad Ziaul Haque, MBBS, M.phil -: 1 :- Table of Contents General Country Profile A. Geography and Population 3 B. History and Culture 7 C. Government and Legal System 9 D. Economy and Employment 10 E. Physical and Technological Infrastructure 14 National Health Care Sector Review A. National Health Care Profile 16 B. National Health Care Structure 24 National Radiology Profile A. Overview of Imaging in Seychelles 27 B. Workforce, Training and Professional Representation 30 C. Radiology Regulation and Policy 32 Conclusion 33 References 36 Appendix A 38 -: 2 :- SEYCHELLES “The Paradise” General Country Profile Figure 1: Seychelles Flag (CIA, 2018) [1] Figure 2: Seychelles Map (CIA, 2018) [1] A. Geography and Population The Republic of Seychelles is an island nation that lies more than 1,500 km from the east coast of Africa and north of Madagascar in the Indian Ocean. Its 155 scattered islands have a combined land area of 455 sqkm with an exclusive economic zone of 200 nm. The islands fall into two main physical types. The islands of the central group, including the main island ‘Mahé’, are formed from granite and consist of a mountainous heart surrounded by a flat coastal strip. The “Outer Islands” are made up of coral accretions at various stages of formation, from reefs to atolls. These are generally smaller and almost entirely flat, lying only a few meters above sea level. The majority of these islands have no water, and only a few are inhabited. The three main islands, housing nearly the entire population, are deemed the “Inner Islands” and include: Mahé, Praslin, and La Digue.