Adopt-A-People. It Is Difficult to Sustain A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Streams of Civilization: Volume 2

Copyright © 2017 Christian Liberty Press i Streams Two 3e TEXT.indb 1 8/7/17 1:24 PM ii Streams of Civilization Volume Two Streams of Civilization, Volume Two Original Authors: Robert G. Clouse and Richard V. Pierard Original copyright © 1980 Mott Media Copyright to the first edition transferred to Christian Liberty Press in 1995 Streams of Civilization, Volume Two, Third Edition Copyright © 2017, 1995 Christian Liberty Press All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, without written permission from the publisher. Brief quota- tions embodied in critical articles or reviews are permitted. Christian Liberty Press 502 West Euclid Avenue Arlington Heights, Illinois 60004-5402 www.christianlibertypress.com Copyright © 2017 Christian Liberty Press Revised and Updated: Garry J. Moes Editors: Eric D. Bristley, Lars R. Johnson, and Michael J. McHugh Reviewers: Dr. Marcus McArthur and Paul Kostelny Layout: Edward J. Shewan Editing: Edward J. Shewan and Eric L. Pfeiffelman Copyediting: Diane C. Olson Cover and Text Design: Bob Fine Graphics: Bob Fine, Edward J. Shewan, and Lars Johnson ISBN 978-1-629820-53-8 (print) 978-1-629820-56-9 (e-Book PDF) Printed in the United States of America Streams Two 3e TEXT.indb 2 8/7/17 1:24 PM iii Contents Foreword ................................................................................1 Introduction ...........................................................................9 Chapter 1 European Exploration and Its Motives -

Catholic Missionaries in Africa

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2009 Catholic missionaries in Africa: the White Fathers in the Belgian Congo 1950-1955 Kathryn Rountree Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Rountree, Kathryn, "Catholic missionaries in Africa: the White Fathers in the Belgian Congo 1950-1955" (2009). LSU Master's Theses. 3278. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/3278 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CATHOLIC MISSIONARIES IN AFRICA: THE WHITE FATHERS AND THE BELGIAN CONGO 1950-1955 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Louisiana State University an Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in The Department of History by Kathryn Rountree B.A. Louisiana State University, 2002 December 2009 Acknowledgments I would like to thank my family, especially my mom, for their support and encouragement throughout this process. Additional thanks go to Peter Van Uffelen for his invaluable role as translator and his hospitality during my stay in Belgium. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments ........................................................................................................................................ -

Parish Magazine of Christ Church Stone

Parish Magazine of Christ Church Stone PARISH DIRECTORY SUNDAY SERVICES Details of our services are given on pages 2 and 3. Young people’s activities take place in the Centre at 9.15 am THE PARISH TEAM Vicar Paul Kingman 812669 The Vicarage, Bromfield Court Parish Administrator Clare Nash (Office) 811990 Electoral Roll Officer Irene Gassor 814871 Parish Office Christ Church Centre, Christ Church Way, Stone, Staffs ST15 8ZB Email [email protected] Youth Worker Thomas Nash 286551 Deaconess (Retired) Ann Butler 818160 Readers David Bell 815775 John Butterworth 817465 Margaret Massey 813403 David Rowlands 816713 Michael Thompson 813712 Cecilia Wilding 817987 Music Co-ordinators Peter Mason 815854 Jeff Challinor 819665 Wardens Phil Tunstall 817028 David Rowlands 816713 Deputy Wardens Shirley Hallam, Arthur Foulkes Prayer Request List Barbara Thornicroft 818700 CHRIST CHURCH CENTRE Booking Secretary Shelagh Sanders (Office) 811990 (Home) 760602 CHURCH SCHOOLS Christ Church C.E.(Controlled) First School, Northesk Street. Head: Mrs Lynne Croxall B.Ed.(Hons) 354125 Christ Church C.E.(Aided) Middle School, Old Road Head: C. Waghorn B.Ed(Hons),DPSE,ACP,FRSA 354047 1 In This Issue Diary for May 2 Elected 4 Liars, Evil Brutes and Lazy Gluttons 5 What a Liberty! 5 Easter Flowers (Thank You) 5 MEGAQUEST Holiday Club 6 Please get your Christ Church Middle School 7 contributions for the June St John the Evangelist Church, Oulton 8 magazine to us Radiance, A feast of Christian Spirituality 9 by 15th May Feba Radio 10 Wedding of Rachel Morray and Paul Swin- 11 son Michelle Parry 12 A Thank You for prayers 12 Mini Keswick heads for a First in Lichfield 13 Little Fishes- Friday Toddler Group 13 PCC News 15 Roads for Prayer 16 From the Registers 16 Cover Story: Jerry Cooper drew lots of wonderful pictures for this magazine, all of them buildings in our parish. -

January 18-22 Arden Presbyterian Church (PCA)

January 18-22 Arden Presbyterian Church (PCA) 2215 Hendersonville Road Arden, NC 28704 ardenpres.org 828-684-7221 2017 Missions Conference Keynote Speaker: Rev. Dr. Lloyd Kim Guest Speakers: Rev. Esaïe Etienne Rev. Keith and Ruth Powlison Rev. Bill and Suzanne Scott Wednesday, January 18 5:00 – 6:15 PM Dinner, Multipurpose Room 6:15 – 7:30 PM Joint Youth & Adult program; Children’s Catechism Class Thursday, January 19 12:30 PM S.U.P.E.R. Saints Luncheon Featuring Keith & Ruth Powlison 2 Friday, January 20 5:30—6:30 PM Missions Dinner (need RSVPs) 6:15—8:00 PM Nursery for children up to age 4 6:30—8:00 PM Introduction of Missionaries Message: Dr. Kim Grades PreK – 5 Missions Program, Fellowship Room, led by Kathy Meeks Saturday, January 21 9:30—11:00 AM Church-Wide Breakfast (need RSVPs) Panel Discussion with Q & A Nursery provided during the panel Sunday, January 22 9:15 – 10:15 AM Joint Sunday School, Chapel 10:45– 12:00 PM Morning Worship Service, Dr. Kim preaching Flag Processional Faith Promise cards received 3 Rev. Dr. Lloyd Kim Lloyd Kim was elected coordina- tor of Mission to the World (MTW) by the 2015 General Assembly. A native of California, he gradu- ated from UC Berkeley with a degree in engineering and worked as a consultant with Ernst & Young before getting his M.Div. at Westminster Seminary in California and his doctorate in New Testament Studies at Fuller Theological Seminary. He was associate pastor with New Life Mission Church (PCA) in Fullerton, Calif., before joining MTW. -

Download Download

Ord, Leaving the Gathered Community 131 Leaving the Gathered Community: Porous Borders and Dispersed Practices Mark Ord A Baptist ecclesiology of the gathered community coupled with a characteristic concern for mission has led to a dynamic of gathering and sending within British Baptist worship. This engenders a demarcation between the church and the world, and a sense of a substantial boundary between the two. In this article I explore the metaphor of the boundary between the church and the world. In doing so, I examine recent theological proposals that present formation as taking place within the worship of the gathered community for the purpose of mission. I propose a picture of the boundary as porous and its formation necessarily occurring, both within the church and the world, through worship and witness. I argue that church–world relations are complex and cannot be described as ‘one way’ — from worship to witness. The article concludes by pointing to the need for sacramental practices for the church in dispersed mode, for example hospitality, as well as for the church gathered, for example baptism and communion. This implies recognising that there are graced practices of the church and indwelt sacramentality which find their rightful place in the context of witness in the world, by leaving the gathered community. Keywords Baptist ecclesiology; sacraments; mission; practices Baptist Ecclesiology: Local, Missional, Individualistic Baptists have long been characterised by ecclesiological concerns for both the local congregation and mission. In his book, Baptist Theology, Stephen Holmes states: ‘There are two foci around which Baptist life is lived: the individual believer and the local church’.1 These are classic concerns for the visible church, ‘gathered by covenant’,2 or as Thomas Helwys expressed it at the start of the seventeenth century, ‘A company of faithful people, separated from the world by the word and Spirit of God […] upon their own confession of faith and sins.’3 Mission does not have quite the same pedigree. -

Vision Anabaino Sm

2 0 1 1 VISION Anabaino PURSUING THE “GREATER THINGS” OF CHRIST’S ASCENDED MINISTRY TODAY! (JN 14:12) A PUBLICATION OF CHRIST PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH Why Mission Anabaino? by Rev. Preston Graham More Than A Strategic Plan, Mission Anabaino Is A Theological Vision In The Simplicity and Purity of Devotion to Christ Applied! In This Issue In strategic terms, “mission consistent impact of dynamic, CPC 135 4 anabaino” is “mission extensive church church planting!” As a planting.1 Church-Planting 6 practical plan, those who have studied the Again in CPC in the Hill 7 issue of church strategic terms, growth and church Keller’s On Campus 9 revitalization have conclusion is concluded with Tim based on Impact Week 10 Keller that studies supporting the Haiti 12 The vigorous, simple continual conclusion that Danbury 14 planting of new congregations new churches best reach new is the single most crucial generations, new residents, new Goatville 15 strategy for 1) the numerical socio-cultural people groups and growth of the Body of Christ the unchurched. The reasons and 2) the continual corporate often noted are understandable if A Shameless Pitch for 16 renewal and revival of existing Mission Anabaino churches. Nothing else--not not always obvious to those who crusades, outreach programs, attend existing churches. It takes para-church ministries, growing no more than five or so years before “cultural hegemony” nnn mega-churches, congregational consulting, nor church renewal begins to set in to the life of a processes--will have the church—when a particular kind of continued on page 2 Why Mission Anabaino? by Rev. -

Mission Continues Global Impulses for the 21St Century Claudia Wahr̈ Isch-Oblau University of Edinburgh, Ir [email protected]

Concordia Seminary - Saint Louis Scholarly Resources from Concordia Seminary Edinburgh Centenary Series Resources for Ministry 1-1-2010 Mission Continues Global Impulses for the 21st Century Claudia Wahr̈ isch-Oblau University of Edinburgh, [email protected] Fidon Mwombeki University of Edinburgh, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholar.csl.edu/edinburghcentenary Part of the Missions and World Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Wahr̈ isch-Oblau, Claudia and Mwombeki, Fidon, "Mission Continues Global Impulses for the 21st Century" (2010). Edinburgh Centenary Series. Book 13. http://scholar.csl.edu/edinburghcentenary/13 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Resources for Ministry at Scholarly Resources from Concordia Seminary. It has been accepted for inclusion in Edinburgh Centenary Series by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Resources from Concordia Seminary. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REGNUM EDINBURGH 2010 SERIES Mission Continues Global Impulses for the 21st Century REGNUM EDINBURGH 2010 SERIES Series Preface The Centenary of the World Missionary Conference, held in Edinburgh 1910, is a suggestive moment for many people seeking direction for Christian mission in the 21st century. Several different constituencies within world Christianity are holding significant events around 2010. Since 2005 an international group has worked collaboratively to develop an intercontinental and multi- denominational project, now known as Edinburgh 2010, and based at New College, University of Edinburgh. This initiative brings together representatives of twenty different global Christian bodies, representing all major Christian denominations and confessions and many different strands of mission and church life, to prepare for the Centenary. -

Mission to the World

Christianity Mission to the World Mission to the World Summary: For all of Christian history, missionaries have traveled across the world with the goal of creating a global church. Following the routes of empire and trade, new Christian traditions arose. Some served the interests of colonizing powers while others, influenced by diverse indigenous cultures and identities, opposed European imperialism. The history of Christian missions is as old as the church, inspired by the commission Christ left his followers to “make disciples of all nations.” Such zeal was seen in the early Syrian Christians who missionized as far as India and China in the early 3rd to 7th centuries. It was also the mission of early Roman monks that first planted churches in Ireland and England, Germany and Northern Europe, and Russia and Eastern Europe. However, the 16th century, which saw both the Protestant Reformation and the Catholic Counter-Reformation, was also the beginning of European colonial expansion and with it, church expansion. The Spanish conquered and colonized in the lands of South America, Mexico, and the Philippines. The Portuguese planted colonies in Brazil, Africa, India, and China. The British Empire included territories in India, Ceylon, Burma, Africa, Australia, and North America. The Dutch were in Indonesia and Africa. The French had colonies in Africa, Southeast Asia, and North America. The spread of Christian churches followed in the tracks of empire, trade, and colonization. At times, the churches and missionaries were involved or complicit in the exploitation and oppression of colonized people. It is also true, however, that missionaries were among the strongest critics of colonial excesses. -

Herald of Holiness Volume 79 Number 01 (1990) Wesley D

Olivet Nazarene University Digital Commons @ Olivet Herald of Holiness/Holiness Today Church of the Nazarene 1-1-1990 Herald of Holiness Volume 79 Number 01 (1990) Wesley D. Tracy (Editor) Nazarene Publishing House Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.olivet.edu/cotn_hoh Part of the Christian Denominations and Sects Commons, Christianity Commons, History of Christianity Commons, Missions and World Christianity Commons, and the Practical Theology Commons Recommended Citation Tracy, Wesley D. (Editor), "Herald of Holiness Volume 79 Number 01 (1990)" (1990). Herald of Holiness/Holiness Today. 97. https://digitalcommons.olivet.edu/cotn_hoh/97 This Journal Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Church of the Nazarene at Digital Commons @ Olivet. It has been accepted for inclusion in Herald of Holiness/Holiness Today by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Olivet. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Board of General Superintendents (left to right): John A. Knight, Donald D. Owens, William J. Prince, Raymond W. Hurn, Jerald D. Johnson, Eugene L. Stowe PROCLAMATION 1990 is our Year of Sabbath. The next 12 months we are tional AIDS crisis, and now serious consideration of doing calling Nazarenes around the world to prayer—“THAT away with civil marriage ceremonies—let alone religious THE WORLD MAY KNOW!” The appeal was first made at ones. In some countries euthanasia is actually being prac the General Assembly this past June when we gave the fol ticed. It now appears that in certain areas drug testing may lowing background for our request: become mandatory, even in elementary schools. -

Locally Generated Printed Materials in Agriculture: Experience from Uganda and Ghana

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Research Papers in Economics Locally Generated Printed Materials in Agriculture: Experience from Uganda and Ghana - Education Research Paper No. 31, 1999, 132 p. Table of Contents EDUCATION RESEARCH Isabel Carter July 1999 Serial No. 31 ISBN: 1 86192 079 2 Department For International Development Table of Contents List of acronyms Acknowledgements Other DFID Education Studies also Available List of Other DFID Education Papers Available in this Series Department for International Development Education Papers 1. Executive summary 1.1 Background 1.2 Results 1.3 Conclusions 1.4 Recommendations 2. Background to research 2.1 Origin of research 2.2 Focus of research 2.3 Key definitions 3. Theoretical issues concerning information flow among grassroots farmers 3.1 Policies influencing the provision of information services for farmers 3.2 Farmer access to information provision 3.3 Farmer-to-farmer sharing of information 3.4 Definition of locally generated materials 3.5 Summary: Knowledge is power 4. Methodology 4.1 Research questions 4.2 Factors influencing the choice of methodologies used 4.3 Phase I: Postal survey 4.4 Phase II: In-depth research with farmer groups 4.5 Research techniques for in-depth research 4.6 Phase III: Regional overview of organisations sharing agricultural information 4.7 Data analysis 5. Phase I: The findings of the postal survey 5.1 Analysis of survey respondents 5.2 Formation and aims of groups 5.3 Socio-economic status of target communities 5.4 Sharing of Information 5.5 Access to sources of information 6. -

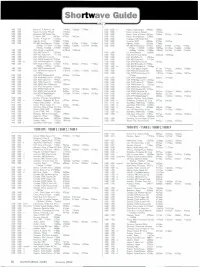

Shortwave Guide

Shortwave Guide 400 1500 Romania, R Romania Intl 11940eu I5365eu 17790eu 500 1 600 d Nigeria, Rodio/Logos 4990do 7287:Vas 400 1500 Russia, University Network 17765os 5W 1 600 Russia, University Network 400 1500 Singapore, SBC Radio One 6150do 5C/0 1 600 Russia, Voice of Russo 6205as 7260na 7315as 157350m 400 1500 Sr Lonka, SLBC 6005os 9770as 15425as 500 1 600 Russo, World Beacon 15340eu 400 1500 Taiwan,R Taipei Intl 15265as 500 1 600 Singapore, SBC Radio One 6150do 400 1500 Uganda, Radio 5026do 7196do 5W 1 600 Sr Lanka, SLBC 6005as 9770as 15425os 400 1500 UK, BBC World Service6135as 6190o1 6195os 9740as 1194001 500 1 600 Ugondo, Radio 5026do 7196do 12095eu 15190om 15310as I 5485eu 15565eu 15575meI 7640eu 500 1 600 UK, BBC World Service 5975os 6135as 6190of 6195as 9410eu 17700os 17830o1 21470of 21660of 9740os 11860x1 I 1940of I2095eu 15190am15400of 15420o1 400 500 USA, Armed Forces Rodio 6458usb I 2689usb I 5485eu 15565eu 17700os I 7830of 21470of 21490of 21660af 400 500 USA, KAIJ Dallas TX 1381 5vo UK, World Beacon I 5340eu 400 500 USA, KJES Vado NM 11715na USA, Armed Forces Radio 6458usb I 2689usb 400 500 USA, KTBN Salt Lk City UT 7510no USA, KAIJ Dallas TX 13815vo 400 500 USA, KWHR Naolehu HI 9930as USA, KJES Vodo NM II 715no 400 500 os USA, KWHR Noolehu HI11 565po USA, KTBN Salt Lk City UT 751 Ono 400 500 USA, Voice of Americo 6110as 7125as 9645as 9760os II 705as USA, KWHR Naalehu HI 9930as 15205as 15395as 15425as as USA, KWHR Noolehu HI 11565pa 400 500 USA, mica Monticello ME I 7495no USA, VOA Special English 6110as 9760os 12040as -

Prayer Focus July -October2016 1 2 These Broadcasts Daily

Prayer Focus July - October 2016 Making followers of Christ through media 1 FEBC China – Liangyou Theological Seminary (continue) JULY Fri 1 – Praise God for the dedicated students Liangyou Theological Seminary (LTS) website. from 20 provinces in China who visited the Hong The download rate of files and additional arti- Kong studios for intensive study camps over the cles, as well as the hit rate for discussions and last few years. the ‘Prayer Room’ have increased dramatically with the new LTS website, attracting millions of Sat 2 – Thank God for the highly interactive downloads and hits per year. FEBC Hong Kong – Radio Liangyou and Radio Yiyou Sun 3 – WEEKLY SUMMARY: FEBC Hong Tue 5 – More than 50 programs are produced Kong is the production center for our Chinese and aired by the staff of these two stations. and other minority languages’ broadcasted pro- Some of the popular programs include Liangyou grams. They coordinate the daily production Theological Seminary, Radio Counselling Corner, of 33.5 hours of programs produced by sever- and Seasons of Life. Pray that God will bless the al FEBC studios in Singapore, Taipei, La Mirada, producers and broadcasters of these programs. Vancouver, Toronto and Hong Kong. More than 32 hours of these programs are available on the Wed 6 – Radio Liangyou and Radio Yiyou re- internet. FEBC Hong Kong’s staff regularly vis- ceive about 78 000 listener responses annually! its their listeners and they also distribute radios, Praise God for this great response rate. Also pray CD’s, and other materials. Join us in prayer this that more people will listen and respond to these week for two of FEBC Hong Kong’s radio sta- stations.