Remote Audiences Beyond 2000 : Radio, Everyday Life and Development in South India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Economic Impact of the Recorded Music Industry in India September 2019

Economic impact of the recorded music industry in India September 2019 Economic impact of the recorded music industry in India Contents Foreword by IMI 04 Foreword by Deloitte India 05 Glossary 06 Executive summary 08 Indian recorded music industry: Size and growth 11 Indian music’s place in the world: Punching below its weight 13 An introduction to economic impact: The amplification effect 14 Indian recorded music industry: First order impact 17 “Formal” partner industries: Powered by music 18 TV broadcasting 18 FM radio 20 Live events 21 Films 22 Audio streaming OTT 24 Summary of impact at formal partner industries 25 Informal usage of music: The invisible hand 26 A peek into brass bands 27 Typical brass band structure 28 Revenue model 28 A glimpse into the lives of band members 30 Challenges faced by brass bands 31 Deep connection with music 31 Impact beyond the numbers: Counts, but cannot be counted 32 Challenges faced by the industry: Hurdles to growth 35 Way forward: Laying the foundation for growth 40 Conclusive remarks: Unlocking the amplification effect of music 45 Acknowledgements 48 03 Economic impact of the recorded music industry in India Foreword by IMI CIRCA 2019: the story of the recorded Nusrat Fateh Ali-Khan, Noor Jehan, Abida “I know you may not music industry would be that of David Parveen, Runa Laila, and, of course, the powering Goliath. The supercharged INR iconic Radio Ceylon. Shifts in technology neglect me, but it may 1,068 crore recorded music industry in and outdated legislation have meant be too late by the time India provides high-octane: that the recorded music industries in a. -

Streams of Civilization: Volume 2

Copyright © 2017 Christian Liberty Press i Streams Two 3e TEXT.indb 1 8/7/17 1:24 PM ii Streams of Civilization Volume Two Streams of Civilization, Volume Two Original Authors: Robert G. Clouse and Richard V. Pierard Original copyright © 1980 Mott Media Copyright to the first edition transferred to Christian Liberty Press in 1995 Streams of Civilization, Volume Two, Third Edition Copyright © 2017, 1995 Christian Liberty Press All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, without written permission from the publisher. Brief quota- tions embodied in critical articles or reviews are permitted. Christian Liberty Press 502 West Euclid Avenue Arlington Heights, Illinois 60004-5402 www.christianlibertypress.com Copyright © 2017 Christian Liberty Press Revised and Updated: Garry J. Moes Editors: Eric D. Bristley, Lars R. Johnson, and Michael J. McHugh Reviewers: Dr. Marcus McArthur and Paul Kostelny Layout: Edward J. Shewan Editing: Edward J. Shewan and Eric L. Pfeiffelman Copyediting: Diane C. Olson Cover and Text Design: Bob Fine Graphics: Bob Fine, Edward J. Shewan, and Lars Johnson ISBN 978-1-629820-53-8 (print) 978-1-629820-56-9 (e-Book PDF) Printed in the United States of America Streams Two 3e TEXT.indb 2 8/7/17 1:24 PM iii Contents Foreword ................................................................................1 Introduction ...........................................................................9 Chapter 1 European Exploration and Its Motives -

Parish Magazine of Christ Church Stone

Parish Magazine of Christ Church Stone PARISH DIRECTORY SUNDAY SERVICES Details of our services are given on pages 2 and 3. Young people’s activities take place in the Centre at 9.15 am THE PARISH TEAM Vicar Paul Kingman 812669 The Vicarage, Bromfield Court Parish Administrator Clare Nash (Office) 811990 Electoral Roll Officer Irene Gassor 814871 Parish Office Christ Church Centre, Christ Church Way, Stone, Staffs ST15 8ZB Email [email protected] Youth Worker Thomas Nash 286551 Deaconess (Retired) Ann Butler 818160 Readers David Bell 815775 John Butterworth 817465 Margaret Massey 813403 David Rowlands 816713 Michael Thompson 813712 Cecilia Wilding 817987 Music Co-ordinators Peter Mason 815854 Jeff Challinor 819665 Wardens Phil Tunstall 817028 David Rowlands 816713 Deputy Wardens Shirley Hallam, Arthur Foulkes Prayer Request List Barbara Thornicroft 818700 CHRIST CHURCH CENTRE Booking Secretary Shelagh Sanders (Office) 811990 (Home) 760602 CHURCH SCHOOLS Christ Church C.E.(Controlled) First School, Northesk Street. Head: Mrs Lynne Croxall B.Ed.(Hons) 354125 Christ Church C.E.(Aided) Middle School, Old Road Head: C. Waghorn B.Ed(Hons),DPSE,ACP,FRSA 354047 1 In This Issue Diary for May 2 Elected 4 Liars, Evil Brutes and Lazy Gluttons 5 What a Liberty! 5 Easter Flowers (Thank You) 5 MEGAQUEST Holiday Club 6 Please get your Christ Church Middle School 7 contributions for the June St John the Evangelist Church, Oulton 8 magazine to us Radiance, A feast of Christian Spirituality 9 by 15th May Feba Radio 10 Wedding of Rachel Morray and Paul Swin- 11 son Michelle Parry 12 A Thank You for prayers 12 Mini Keswick heads for a First in Lichfield 13 Little Fishes- Friday Toddler Group 13 PCC News 15 Roads for Prayer 16 From the Registers 16 Cover Story: Jerry Cooper drew lots of wonderful pictures for this magazine, all of them buildings in our parish. -

Pvt. C&S Tv Channels

[ Lok Sabha Unstarred Question No. 3416 'Annexure‐I' " ] PVT. C&S TV CHANNELS Sl.No. Sl.No. Genre Channel Name all Star Plus Colors Viacom18 Z Zee TV LIFE OK SONY ENTERTAINMENT TV 1 Hindi GEC SONY SAB Star Utsav Sahara One BIG Magic Z Smile 9X Aaj Tak ABP News India TV Zee News India News NDTV India News 24 IBN 7 Samay 2 Hindi News Tez P7 news NEWS EXPRESS Live India 4 REAL NEWS Disha Channel Total TV SHRI NEWS Sudarshan News Janta TV Channel One News KHABRAIN ABHI TAK A2Z News Aryan TV Aap Ki Awaaz Azad News Khoj India Jain TV GNN News Khabar Bharti Lemon TV99 Zee Cinema Star Gold SONY MAX UTV Movies UTV Action Z Classic 3 Hindi Movie FILMY B4U Movies Z Action Z Premier Enter 10 Television Manoranjan TV V UTV Bindass 4 Hindi Music MTV SONY MIX 9X M Mastii B4U Music Z ETC Music Express Z Business CNBC Awaaz CNBC TV 18 5 Business Channel ET Now NDTV Profit Bloomberg UTV POGO CN Cartoon Network 6 Kids Channel NICK SONIC Zoom Zing Food Food Hindi Life Style NDTV Good Times 7 Channel ZEE KHANA KHAZANA Zee Trendz Vision Shiksha Vision TV Aastha Sanskar Divya Bhakti TV 8 Hindi Spiritual Z Jagran Sadhna Aastha Bhajan SANATAN TV KAATYAYANI Jinvani Dilli Aaj Tak Sahara Samay NCR Har Raj Regional News 9 INDIA NEWS HARYANA Delhi TAAZA TV Perls NCR-Har - Raj AXN Z Cafe 10 English GEC BIG CBS LOVE BIG CBS PRIME BBC ENTERTAINMENT NDTV 24X7 CNN/IBN Times Now Headlines Today 11 English News News X NEWS 9 HY TV AYUR LIVING INDIA HBO SONY PIX Movies Now 12 English Movie Z Studio UTV WORLD MOVIES Firangi VH1 13 English Music BIG CBS SPARK Star Jalsha 14 Bangla GEC Z Bangla ETV Bangla Aakash Bangla RUPASHI BANGLA ABP Ananda 24 Ghanta Kolkata TV 15 Bangla News NEWS TIME BANGLA RPLUS Channel 10 S BANGLA 16 Bangla Music Dhoom Music Tara Music 17 Bangla Movie SONY AATH Mahuaa Sobhagya Mithila Hamar TV 18 Bihar GEC TV100 Himalaya Raftaar Maurya TV Pvt. -

A Study on the Role of Public and Private Sector Radio in Women's

Athens Journal of Mass Media and Communications- Volume 4, Issue 2 – Pages 121-140 A Study on the Role of Public and Private Sector Radio in Women’s Development with Special Reference to India By Afreen Rikzana Abdul Rasheed Neelamalar Maraimalai† Radio plays an important role in the lives of women belonging to all sections of society, but especially for homemakers to relieve them from isolation and help them to lighten their spirit by hearing radio programs. Women today play almost every role in the Radio Industry - as Radio Jockeys, Program Executives, Sound Engineers and so on in both public and private radio broadcasting and also in community radio. All India Radio (AIR) constitutes the public radio broadcasting sector of India, and it has been serving to inform, educate and entertain the masses. In addition, the private radio stations started to emerge in India from 2001. The study focuses on private and public radio stations in Chennai, which is an important metropolitan city in India, and on how they contribute towards the development of women in society. Keywords: All India Radio, private radio station, public broadcasting, radio, women’s development Introduction Women play a vital role in the process of a nation’s change and development. The Indian Constitution provides equal status to men and women. The status of women in India has massively transformed over the past few years in terms of their access to education, politics, media, art and culture, service sectors, science and technology activities etc. (Agarwal, 2008). As a result, though Indian women have the responsibilities of maintaining their family’s welfare, they also enjoy more liberty and opportunities to chase their dreams. -

Audio Production Techniques (206) Unit 1

Audio Production Techniques (206) Unit 1 Characteristics of Audio Medium Digital audio is technology that can be used to record, store, generate, manipulate, and reproduce sound using audio signals that have been encoded in digital form. Following significant advances in digital audio technology during the 1970s, it gradually replaced analog audio technology in many areas of sound production, sound recording (tape systems were replaced with digital recording systems), sound engineering and telecommunications in the 1990s and 2000s. A microphone converts sound (a singer's voice or the sound of an instrument playing) to an analog electrical signal, then an analog-to-digital converter (ADC)—typically using pulse-code modulation—converts the analog signal into a digital signal. This digital signal can then be recorded, edited and modified using digital audio tools. When the sound engineer wishes to listen to the recording on headphones or loudspeakers (or when a consumer wishes to listen to a digital sound file of a song), a digital-to-analog converter performs the reverse process, converting a digital signal back into an analog signal, which analog circuits amplify and send to aloudspeaker. Digital audio systems may include compression, storage, processing and transmission components. Conversion to a digital format allows convenient manipulation, storage, transmission and retrieval of an audio signal. Unlike analog audio, in which making copies of a recording leads to degradation of the signal quality, when using digital audio, an infinite number of copies can be made without any degradation of signal quality. Development and expansion of radio network in India FM broadcasting began on 23 July 1977 in Chennai, then Madras, and was expanded during the 1990s, nearly 50 years after it mushroomed in the US.[1] In the mid-nineties, when India first experimented with private FM broadcasts, the small tourist destination ofGoa was the fifth place in this country of one billion where private players got FM slots. -

Locally Generated Printed Materials in Agriculture: Experience from Uganda and Ghana

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Research Papers in Economics Locally Generated Printed Materials in Agriculture: Experience from Uganda and Ghana - Education Research Paper No. 31, 1999, 132 p. Table of Contents EDUCATION RESEARCH Isabel Carter July 1999 Serial No. 31 ISBN: 1 86192 079 2 Department For International Development Table of Contents List of acronyms Acknowledgements Other DFID Education Studies also Available List of Other DFID Education Papers Available in this Series Department for International Development Education Papers 1. Executive summary 1.1 Background 1.2 Results 1.3 Conclusions 1.4 Recommendations 2. Background to research 2.1 Origin of research 2.2 Focus of research 2.3 Key definitions 3. Theoretical issues concerning information flow among grassroots farmers 3.1 Policies influencing the provision of information services for farmers 3.2 Farmer access to information provision 3.3 Farmer-to-farmer sharing of information 3.4 Definition of locally generated materials 3.5 Summary: Knowledge is power 4. Methodology 4.1 Research questions 4.2 Factors influencing the choice of methodologies used 4.3 Phase I: Postal survey 4.4 Phase II: In-depth research with farmer groups 4.5 Research techniques for in-depth research 4.6 Phase III: Regional overview of organisations sharing agricultural information 4.7 Data analysis 5. Phase I: The findings of the postal survey 5.1 Analysis of survey respondents 5.2 Formation and aims of groups 5.3 Socio-economic status of target communities 5.4 Sharing of Information 5.5 Access to sources of information 6. -

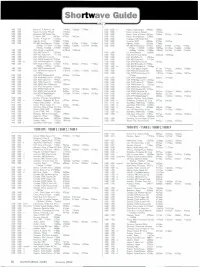

Shortwave Guide

Shortwave Guide 400 1500 Romania, R Romania Intl 11940eu I5365eu 17790eu 500 1 600 d Nigeria, Rodio/Logos 4990do 7287:Vas 400 1500 Russia, University Network 17765os 5W 1 600 Russia, University Network 400 1500 Singapore, SBC Radio One 6150do 5C/0 1 600 Russia, Voice of Russo 6205as 7260na 7315as 157350m 400 1500 Sr Lonka, SLBC 6005os 9770as 15425as 500 1 600 Russo, World Beacon 15340eu 400 1500 Taiwan,R Taipei Intl 15265as 500 1 600 Singapore, SBC Radio One 6150do 400 1500 Uganda, Radio 5026do 7196do 5W 1 600 Sr Lanka, SLBC 6005as 9770as 15425os 400 1500 UK, BBC World Service6135as 6190o1 6195os 9740as 1194001 500 1 600 Ugondo, Radio 5026do 7196do 12095eu 15190om 15310as I 5485eu 15565eu 15575meI 7640eu 500 1 600 UK, BBC World Service 5975os 6135as 6190of 6195as 9410eu 17700os 17830o1 21470of 21660of 9740os 11860x1 I 1940of I2095eu 15190am15400of 15420o1 400 500 USA, Armed Forces Rodio 6458usb I 2689usb I 5485eu 15565eu 17700os I 7830of 21470of 21490of 21660af 400 500 USA, KAIJ Dallas TX 1381 5vo UK, World Beacon I 5340eu 400 500 USA, KJES Vado NM 11715na USA, Armed Forces Radio 6458usb I 2689usb 400 500 USA, KTBN Salt Lk City UT 7510no USA, KAIJ Dallas TX 13815vo 400 500 USA, KWHR Naolehu HI 9930as USA, KJES Vodo NM II 715no 400 500 os USA, KWHR Noolehu HI11 565po USA, KTBN Salt Lk City UT 751 Ono 400 500 USA, Voice of Americo 6110as 7125as 9645as 9760os II 705as USA, KWHR Naalehu HI 9930as 15205as 15395as 15425as as USA, KWHR Noolehu HI 11565pa 400 500 USA, mica Monticello ME I 7495no USA, VOA Special English 6110as 9760os 12040as -

SL NO. AGENCY NAME STATE 1 BIG FM Tirupati ANDHRA PRADESH 2 SFM Tirupathi ANDHRA PRADESH 3 SFM Vijaywada ANDHRA PRADESH 4 SFM Ra

List of Pvt FM to whom BOC issued advertisement during 2016-17 SL NO. AGENCY NAME STATE 1 BIG FM Tirupati ANDHRA PRADESH 2 SFM Tirupathi ANDHRA PRADESH 3 SFM Vijaywada ANDHRA PRADESH 4 SFM Rajamundri ANDHRA PRADESH 5 Radio Mirchi-Vijaywada ANDHRA PRADESH 6 Radio City Vizag ANDHRA PRADESH 7 Radio Mirchi 98.3, Vishakhapatnam ANDHRA PRADESH 8 Gup-Shup 94.3 FM Guwahati ASSAM 9 BIG FM Guwahati ASSAM 10 Red FM Guwahati ASSAM 11 Radio Mirchi-Patna BIHAR 12 Radio Dhamaal - Muzaffarpur BIHAR 13 My FM - Chandigarh CHANDIGARH 14 Radio Mirchi-Rajkot CHHATTISGARH 15 My FM Bilaspur CHHATTISGARH 16 My Fm 94.3 Raipur CHHATTISGARH 17 Radio Tadka Raipur CHHATTISGARH 18 ISHQ FM - DELHI DELHI 19 Hit 95 FM Delhi DELHI 20 Fever 104 FM Bangalore DELHI 21 BIG FM Vishakhapatnam DELHI 22 Best FM Thrissur DELHI 23 Best FM, Kannur DELHI 24 Radio City Surat DELHI 25 Rangila Raipur DELHI 26 RED FM Cochin DELHI 27 Fever 104- Delhi DELHI 28 Radio City-Nagpur DELHI 29 Radio City-jalgaon DELHI 30 Aamar FM- Kolkatta DELHI 31 Power FM- Kolkatta DELHI 32 Radio One -Delhi DELHI 33 Suryan FM Tirunelveli DELHI 34 Visakha FM Suryan DELHI 35 RADIO MIRCHI, DELHI DELHI 36 SURYAN FM Chennai DELHI 37 RED FM, DELHI DELHI 38 Radio City Delhi DELHI 39 BIG FM Panaji GOA 40 Indigo Panaji GOA 41 My FM 94.3 Ahmedabad GUJARAT 42 Red FM Ahmedabad GUJARAT 43 Radio One 94.3 FM, Ahmedabad GUJARAT 44 BIG FM Rajkot GUJARAT 45 Big FM Baroda GUJARAT 46 RADIO MIRCHI, AHMEDABAD GUJARAT 47 Radio City-Baroda GUJARAT 48 Radio Mirchi Surat GUJARAT 49 Radio Mirchi-Baroda GUJARAT 50 Radio Mirchi-Raipur -

Prayer Focus July -October2016 1 2 These Broadcasts Daily

Prayer Focus July - October 2016 Making followers of Christ through media 1 FEBC China – Liangyou Theological Seminary (continue) JULY Fri 1 – Praise God for the dedicated students Liangyou Theological Seminary (LTS) website. from 20 provinces in China who visited the Hong The download rate of files and additional arti- Kong studios for intensive study camps over the cles, as well as the hit rate for discussions and last few years. the ‘Prayer Room’ have increased dramatically with the new LTS website, attracting millions of Sat 2 – Thank God for the highly interactive downloads and hits per year. FEBC Hong Kong – Radio Liangyou and Radio Yiyou Sun 3 – WEEKLY SUMMARY: FEBC Hong Tue 5 – More than 50 programs are produced Kong is the production center for our Chinese and aired by the staff of these two stations. and other minority languages’ broadcasted pro- Some of the popular programs include Liangyou grams. They coordinate the daily production Theological Seminary, Radio Counselling Corner, of 33.5 hours of programs produced by sever- and Seasons of Life. Pray that God will bless the al FEBC studios in Singapore, Taipei, La Mirada, producers and broadcasters of these programs. Vancouver, Toronto and Hong Kong. More than 32 hours of these programs are available on the Wed 6 – Radio Liangyou and Radio Yiyou re- internet. FEBC Hong Kong’s staff regularly vis- ceive about 78 000 listener responses annually! its their listeners and they also distribute radios, Praise God for this great response rate. Also pray CD’s, and other materials. Join us in prayer this that more people will listen and respond to these week for two of FEBC Hong Kong’s radio sta- stations. -

March - June 2019

PRAYER FOCUS March - June 2019 1 FEBC Japan (Continued) MARCH Sat 2 – In a country like Japan where there Fri 1 – A listener from Japan struggled with are very few Christians, there is a great need an eating disorder, but once she started lis- for the gospel. Pray that Pastor Sekino, who tening to FEBC’s broadcasts, she gave her life is one of FEBC’s broadcasters, will capture to Jesus and is completely set free. Praise the hearts of the youth and inspire them to the Lord for his goodness! draw near to Christ. FEBC Australia Sun 3 – WEEKLY SUMMARY: FEBC Aus- Thu 7 – The team is in need of godly, gifted tralia supports 16 FEBC & FEBA ministry fields and competent people to join their mission and also the shortwave broadcasts to ethnic team in order to expand the work. Please minorities throughout Southeast Asia. They pray that those responsible for recruitment also provide thousands of radios & speaker will apply wisdom and discernment when boxes annually for distribution international- choosing candidates. ly. Recently they donated 1000 speaker box- es to FEBA Malawi and a similar amount to Fri 8 – Pray that God will continue to bless FEBC Thailand. They walk in faith and are the Australian people and that out of their fully dependent on God to accomplish FEBC’s abundance they will be inspired to gener- mission to inspire people to follow Jesus. Join ously support the work of God through FEBC us in prayer this week for FEBC Australia. Australia. Mon 4 – FEBC Australia hopes to inspire peo- Sat 9 – Please pray for Director Kevin Keegan ple to support their ministry as they share and his team which is very small with only 2 the power of God through FEBC and FEBA in full time and 3 part-time staff members. -

September 2008 Minreport

individuals and churches have access to a variety of materials in a more timely manner than ever before. In This Issue Methods of design and implementation change, and materials produced for an event are handled more Congregational Support creatively and with greater speed than the year before – Abuse Prevention or the month before! Chaplaincy Ministries For an example of this widespread networking, Disability Concerns check out Abuse Awareness 2008 on the web Dynamic Youth Ministries www.crcna.org/order . Individuals and churches can Faith Alive Christian Resources order a wider array of materials and resources than ever Pastor Church Relations before and most of it available by a click of a button into a Service Link virtual “shopping cart”. Diaconal Ministries CRWRC Partners Worldwide Chaplaincy Ministries Educational Institutions Calvin College Chaplaincy Ministries transcends many boundaries both Mission Organizations outside and within the Christian Reformed Church. Back to God Ministries International Our work takes us beyond the organizations of the Home Missions CRCNA. Not only Calvin Theological Seminary, but other World Missions seminaries, and our colleges are contacted for recruitment. We contact every calling church, every classis, and every employer—civilian and military—for endorsement of chaplains for ministry. Abuse Prevention We are in contact with The American Association of Pastoral Counselors, the Association of Clinical Pastoral The well-worn expression, “It takes a village…” applies to Education, the Association of Professional Chaplains, the the ministry of Abuse Prevention. The ministry relies on a Canadian Association of Pastoral Practice and “village” of volunteers, colleagues and web sites to make Education, and the Council on Collaboration when resources and information available to individuals and to working toward standardization of credentialing our churches.