Ruta Sepetys ILB 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Salt to the Sea : a Novel / Ruta Sepetys

ALSO BY RUTA SEPETYS Between Shades of Gray Out of the Easy PHILOMEL BOOKS an imprint of Penguin Random House LLC 375 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014 Text copyright © 2016 by Ruta Sepetys. Map illustrations copyright © 2016 by Katrina Damkoehler. Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader. Philomel Books is a registered trademark of Penguin Random House LLC. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Sepetys, Ruta. Salt to the sea : a novel / Ruta Sepetys. pages cm Summary: “As World War II draws to a close, refugees try to escape the war’s final dangers, only to find themselves aboard a ship with a target on its hull”—Provided by publisher. 1. World War, 1939–1945—Juvenile fiction. [1. World War, 1939–1945—Fiction. 2. Refugees—Fiction.] I. Title. PZ7.S47957Sal 2016 [Fic]—dc23 2015009057 ISBN 978-0-698-17262-3 This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, businesses, companies, events, or locales is entirely coincidental. JACKET IMAGES: IMAGE DEPOT PRO, DOUG ARMAND PHOTO ILLUSTRATION: TRAVIS COMMEAU DESIGN -

Auksjon, Som Vanlig Tidfestet We Welcome All Customers, New and Old, to Our Summer Auction Event of Trygt Inne I Fellesferien

Kjære kunde! Dear customer! Vi ønsker velkommen til årets sommerauksjon, som vanlig tidfestet We welcome all customers, new and old, to our summer auction event of trygt inne i fellesferien. Vi presenterer over 6800 objekter og utrop 187. We present more than 6800 lot numbers, and a total estimate close to 8.4 million NOK. samlet knapt 8.4 millioner. The Friday auction comprises a broad offer of numismatics items. Fredagsauksjonen inneholder et sedvanlig bredt spekter av numis- Among others good section Norwegian banknotes, very good coins on matiske objekter, bl.a. bra avdeling norske sedler, svenske mynter, Sweden and Russian, a vast number of modern silver and gold medal tallrike sølv- og gull medalje- og myntsett fra mange land og et and coin sets from many countries. meget interessant avsnitt gamle russiske mynter. Further on Friday for instance good offers on jewels, silverware, comic Videre på fredag har vi bl.a. gode avdelinger bøker, meget omfat- books (very good Danish collection Anders And), old commercial metal signs, books, good mineral collection, old stocks, militaria items, etc. tende utbud reklameskilt, og mange smykker og sølvtøy. The Saturday sale starts as usual with Nordic area, of which we mention Lørdag starter auksjonen som vanlig med avdeling Norden, der vi Finland in particular. However also strong section with several unusual spesielt framhever Finland denne gangen, men også meget variert items from the other countries. med mange meget gode objekter på de andre landene. Utenfor Further to Europe and Overseas we mention good Malaya (with two Norden nevner vi gode avdelinger USA, China, Japan, Malaysia med very good collections), much China and Japan, good USA. -

CHOICES 2017 READING LISTS Children’S Choices Teachers’ Choices Young Adults’ Choices from the Executive Director

CHOICES 2017 READING LISTS Children’s Choices Teachers’ Choices Young Adults’ Choices From the Executive Director hen it comes to engaging students with reading, we know the importance of choice. We know that when students can CHILDREN’S W select the books they want to read, with topics in which they are truly interested, they are more likely not only to read them, but also to understand and to reflect upon them. CHOICES With that in mind, we are delighted to bring to you the 2017 Choices Reading Lists—Children’s Choices, Teachers’ Choices, and Young Adults’ Choices. These highly anticipated lists come just in time, whether you’re looking to squeeze in some summer reading of your 2017 Reading List own or with your children, to build up your classroom library for the fall, or to add new favorites to your curriculum. Beginning Readers The best part is these annual lists are chosen by students and educators themselves, so you know they will please children from our (Grades K–2, Ages 5–8) youngest readers to our most selective teenagers. Young Readers We know this because choice matters—and it can make all the (Grades 3–4, Ages 8–10) difference. Advanced Readers (Grades 5–6, Ages 10–12) Marcie Craig Post Executive Director Contents Children’s Choices ...............................3 Beginning Readers .......................4 Young Readers ............................10 Advanced Readers ..................... 15 Teachers’ Choices ..............................23 Primary Readers .........................24 Intermediate Readers ................26 Advanced Readers .....................28 Young Adults’ Choices ...................... 31 2 What Is the Children’s Choices List? Cat in the Night Madeleine Dunphy. Ill. -

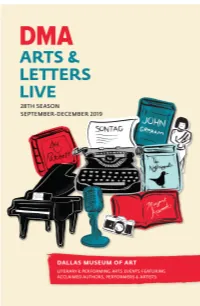

DMA.Org/ALL 1 HOW to ORDER TICKETS

DMA.org/ALL 1 HOW TO ORDER TICKETS DMA.org/ALL This is the FASTEST way to get your tickets! 214-922-1818 Purchase at the Visitor Services Desk anytime during Museum hours. Give the gift of Arts & Letters Live tickets to your family and friends! BOOKS AND SIGNINGS All purchases made in the DMA Store support the Museum. Many of the books will be available for pre-order online at shopDMA.org, and you can pick them up the night of the event. DMA Members and Arts & Letters Live Season Supporters receive discounts on book purchases. "This series continues to thrill and excite DMA MEMBERS me. You have made your mark on Dallas." DMA Members get more. —Arts & Letters Live attendee More benefits. More access. More fun! Join or renew today and get • FREE parking • FREE special exhibition tickets • Discounts in the DMA Store and DMA Cafe and on select programming, including Arts & Letters Live! DMA.org/members All programs, participants, pricing, and venues are subject to change. Tickets are nonrefundable. Ticket holders receive half-price parking in the DMA's garage. For information on venues, parking, dining, services for the hearing impaired, and the DMA Store, visit DMA.org. “I have been attending Arts & Check DMA.org/ALL for more details and newly added events. Letters Live events for 15–20 years and have yet to be STAFF Director of Arts & Letters Live: Carolyn Bess; Program Managers: disappointed by listening to Michelle Witcher and Jessica Laskey; Audience Relations Coordinator: an author speak. Excellent Jennifer Krogsdale; Administrative Coordinator: Carolyn Hartley; and TIMELY program.” Volunteer Coordinator: Andi Orkin; McDermott Intern: Lillie Burrow 2 DMA.org/ALL DMA.org/ALL 3 —Arts & Letters Live attendee BOOK CLUB MODERATORS Dr. -

A Discussion Guide to Salt to the Sea by Ruta Sepetys

THE #1 NEW YORK TIMES BESTSELLER WINNER of the CARNEGIE MEDAL A Discussion & Research Guide RUTA SEPETYS TO SALTTHE SEA Those who are gone are not necessarily lost. Author’s Note This book is a work of historical fi ction. The Wilhelm Gustloff, the Amber Room, and Operation Hannibal, however, are very real. The sinking of the Wilhelm Gustloff is the deadliest disaster in maritime history, with losses dwarfi ng the death tolls of the famous ships Titanic and Lusitania. Yet remarkably, most people have never heard of it. On January 30, 1945, four torpedoes waited in the belly of Soviet submarine S-13. Each torpedo was painted with a scrawled dedication: For the Motherland. For the Soviet People. For Lenin- grad. For Stalin. Three of the four torpedoes were launched, destroying the Wilhelm Gustloff and killing estimates of more than nine thousand people. The majority of the passengers on the Gustloff were civilians, with an estimated fi ve thousand being children. The ghost ship, as it is sometimes called, now lies off the coast of Poland, the large gothic letters of her name still visible underwater. Over two million people were successfully evacuated during Operation Hannibal, the largest sea evacuation in modern history. Hannibal quickly transported not only soldiers but also civilians to safety from the advancing Russian troops. Lithuanians, Latvians, Estonians, ethnic Germans, and residents of the East Prussian and Polish corridors all fl ed toward the sea. My father’s cousins were among them. My father, like Joana’s mother, waited in refugee camps hoping to return to Lithuania. -

Refugee Discussion Guide | Scholastic

DISCUSSION GUIDE AGES 9–12 GRADES 4–7 “Some novels are engaging and some novels are important. Refugee is both.” —Ruta Sepetys, #1 New York Times bestselling author of Salt to the Sea “An incredibly important, heartrending, edge-of-the-seat read.” —Pam Muñoz Ryan, author of the Newbery Honor Book Echo “Full of struggle, heroism, and non-stop adventure. terrific.” —Kimberly Brubaker Bradley, author of the Newbery Honor Book The War That Saved My Life REFUGEE by ALAN GRATZ About Refugee Three young people are looking for refuge, a place for themselves and their families to live in peace. Separated by decades in time and by oceans in geography, their stories share similar emotional traumas and desperate situations.. and, at the end, connect in astounding ways. Josef in 1930s Nazi Germany, Isabel in 1990s Cuba, and Mahmoud in present-day Syria—all three hang on to their hope for a new tomorrow in the face of harrowing dangers. H“ Nothing short of brilliant.”—Kirkus Reviews, starred review H“ Gratz skillfully intertwines the stories of three protagonists… filled with both tragic loss and ample evidence of resilience, these memorable and tightly plotted stories contextualize and give voice Hardcover: to the current refugee crisis.”—Publishers Weekly, starred review 978-0-545-88083-1 • $16.99 Also available in ebook and audio formats. About the Author Alan Gratz is the acclaimed author of several books for young readers, including Prisoner B-3087, which was named to YALSA’s Best Fiction for Young Adults list; Code of Honor, a YALSA Quick Pick; and Projekt 1065; a Kirkus Best Book of the Year. -

Military History Anniversaries 16 Thru 31 January

Military History Anniversaries 16 thru 31 January Events in History over the next 15 day period that had U.S. military involvement or impacted in some way on U.S military operations or American interests JAN 16 1776 – Amrican Revolutionary War: African-American Soldiers » It was an uncomfortable fact for many in the colonies that at the same time they were fighting the British for their liberty and freedom they were depriving slaves of that same opportunity. African-American soldiers, in fact, had participated in major Revolutionary War battles from its very start: around 5% of American forces at the battle of Bunker Hill were black. New England units were completely integrated with soldiers receiving the same pay regardless of color. Still, fears of a rebellion of armed slaves tempered official American recognition of the contribution of blacks. On this date General George Washington allowed for the first time for free blacks with military experience to enlist in the revolutionary army. A year later, as the American need for manpower increased, Washington dropped the military experience requirement, allowing any free black who so wishes to enlist. The Continental Congress tried to recruit more African-Americans by offering to purchase them from the Southern slaveholders. Unsurprisingly, few agreed. But enterprising states like Rhode Island made an end run around the slaveholders, announcing any slave who enlisted would immediately be freed. (Rhode Island compensated the slaveholder for the market value of their slave.) The “1st Rhode Island Regiment” was comprised mostly of those freed slaves, becoming the only Continental Army unit to have segregated units for blacks. -

WGHS Summer Reading 2021-2022 Brochure

West Genesee High School’s Summer Reading Program 2021-2022 For over 20 years, the English Department has sponsored a Summer Reading Program for students entering grades 9-12. The philosophy behind the program has always remained the same: to encourage students to read more by introducing them to contemporary novels that are pleasurable, yet worthwhile stories in the hope that they will become lifelong readers. Each child is required to read one title from the list for the upcoming grade level. A committee of parents, students, and teachers has selected the list for each grade level. Effort has been made to address relevant issues in a responsible and thoughtful manner. Consideration has also been given to include books that offer a range of reading levels. It is our hope that this program will be a shared experience between students and parents. Therefore, it is highly recommended that parents assist their child in the selection of a book that is appropriate for him/her. Parents are encouraged to visit the West Genesee High School Library website for the lists, information about locating books, and access to book reviews. The individual classroom English teacher will assign a project based on the books when the students return to class in September. We advise that students take notes or keep a journal as they read so they can better recall information which will be reviewed and assessed in their respective English classes when they return to school in September. Students enrolled in Advanced Placement English will complete the readings assigned by those teachers in lieu of one of the novels from this list. -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT: Emily Stack Davis September 15, 2017 (517) 607-2730 [email protected] Hillsdale College Hono

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT: Emily Stack Davis September 15, 2017 (517) 607-2730 [email protected] Hillsdale College Honors Alumni at Homecoming Banquet Notable graduates to be recognized for achievement and service at 66th Annual Awards Banquet Hillsdale, Mich. – Hillsdale College will host its 66th Annual Awards Banquet on Sept. 29, when several out- standing Hillsdale graduates will be presented with distinguished alumni awards by their alma mater. “Our alumni don’t do their amazing work for an award like this, but the chance to honor their achievements and spirit of service at this banquet is something we look forward to each year,” said Grigor Hasted, director of alumni relations at Hillsdale College. “The 2017 award recipients are excellent examples of what we hope a Hillsdale education calls forth in all of our students.” The College’s annual banquet gathers Hillsdale alumni and supporters during homecoming as notable graduates are given awards recognizing their professional achievement and philanthropic service to Hillsdale. This year’s honorees include: James Duane Taylor, Class of 1955 Duane is a former CEO of Recreation Creations and a longtime employee of Consumer’s Energy Power Com- pany. Additionally, he served with the U.S. Army from 1955-1957, including a tour in Korea, and held leader- ship roles on the Hillsdale Community School Board, Key Opportunities Board, and Alpha Tau Omega Alumni Board. Duane participates in the Junior Chamber of Commerce, serves at the First Presbyterian Church of Hills- dale and is also a member of the College’s President’s Club. Duane completed a bachelor’s degree in business at Hillsdale College in 1955 and in 1961 earned his MBA from Western Michigan University. -

Salt to the Sea (Thorndike Press Large Print Literacy Bridge Series) Online

1URQw [Download free pdf] Salt To The Sea (Thorndike Press Large Print Literacy Bridge Series) Online [1URQw.ebook] Salt To The Sea (Thorndike Press Large Print Literacy Bridge Series) Pdf Free Ruta Sepetys *Download PDF | ePub | DOC | audiobook | ebooks Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #695562 in Books 2016-08-03Format: Large PrintOriginal language:English 8.50 x 5.75 x 1.00l, .0 #File Name: 1410492877450 pages | File size: 56.Mb Ruta Sepetys : Salt To The Sea (Thorndike Press Large Print Literacy Bridge Series) before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised Salt To The Sea (Thorndike Press Large Print Literacy Bridge Series): 119 of 122 people found the following review helpful. Salt to the SeaBy Leeanna ChetskoIrsquo;ve studied World War II for years. Irsquo;ve read countless books, both nonfiction and fiction, and watched a lot of documentaries. My undergrad degree is even in history. But somehow, before SALT TO THE SEA, Irsquo;d only heard about the Wilhelm Gustloff once.One mention of such an immense tragedy.Irsquo;m thankful to Ruta Sepetys for writing SALT TO THE SEA. I always enjoy historical fiction that introduces me to something I didnrsquo;t know before, which she certainly does. But more than that, the author has such a deft, confident hand that I could sense the amount of research she did and the respect she has for the survivors and victims of the Wilhelm Gustloff. Sepetys doesnrsquo;t overwhelm you with her knowledge, but inserts it subtly, weaving it into the backstories, thoughts, and actions of the characters.SALT TO THE SEA is told through the eyes of four characters. -

Análisis De Los Hundimientos De Buques De Carga Y Pasaje Durante La Segunda Guerra Mundial

Análisis de los hundimientos de buques de carga y 4 de febrero pasaje durante la 2013 Segunda Guerra Mundial Autor: Angel Sevillano Maldonado Tutor: Francesc Xavier Martínez de Osés Diplomatura en Navegación Marítima Trabajo Final de Carrera Facultad de Náutica de Barcelona – UPC DEDICATORIA A mis hermanas, por todo el apoyo e interés mostrado hacia este trabajo. AGRADECIMIENTOS Al primer oficial Néstor Rodríguez, del buque Playa de Alcudia, por darme a conocer muchos de los desastres analizados en el trabajo, al profesor Xavier Martínez de Osés, por su gran colaboración y a todos aquellos que me han brindado su ayuda cuando ha sido necesario. Gracias a todos. Análisis de los hundimientos de buques de carga y pasaje durante la Segunda Guerra Mundial INDICE 1. INTRODUCCIÓN ................................................................................... 9 2. LA SEGUNDA GUERRA MUNDIAL .......................................................10 2.1 INTRODUCCIÓN ...............................................................................10 2.2 PRINCIPALES ESCENARIOS DEL TEATRO BÉLICO..........................12 2.2.1 LA GUERRA DEL PACIFICO ..............................................................12 2.2.2 LA GUERRA SUBMARINA DEL MAR BÁLTICO.............................17 3. ANÁLISIS DE LOS NAUFRAGIOS.........................................................20 3.1 MV WILHELM GUSTLOFF..................................................................20 3.1.1 DATOS GENERALES DEL BUQUE ..............................................20 3.1.2 -

Nazi German Filmography & Tvography

Nazi German Filmography & TVography-1 Nazi German Filmography Compiled from publications by Sabine Hake, German National Cinema, 2nd ed. (2008), and Axel Bangert, The Nazi Past in Contemporary Germany (2014). Tended to exclude Holocaust related, but if a film was set in a concentration camp with a non-Jewish subject focus, I included here. I have a separate Holocaust filmography. I did include costume dramas, fictional characters set in historical events, and films claiming to be a historical account. Some documentaries are included if I bumped into them or found them referenced by Bangert and Hake. (21 July 2018) Film Title (English titles listed Year Director and Description. ahead of original German titles) 12th Man, The (Den 12. 2018 Dir. Harald Zwart. Inspired by a true story of Jan Baalsrud’s escape from the Nazis after mann) having been captured as a resistance fighter. According to the Wiki description this film emphasizes Baalsrud’s rescuers. 13 Minutes (Elser – Er 2015 Dir. Oliver Hirschbiegel. “…tells the true story of George Elser’s failed attempt to hätte die Welt assassinate Adolf Hitler in November 1939.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/13_Minutes verändert) 2 or 3 Things I know 2005 Dir. Malte Ludin. “… is a documentary film in which German director Malte Ludin examines about Him (2 oder 3 the impact of Nazism in his family. Malte's father, Hanns Ludin, was the Third Reich's Dinge, die ich von ihm ambassador to Slovakia. As such, he signed deportation orders that sent thousands of Jews weiβ) to Auschwitz. Hanns Ludin was executed for war crimes in 1947.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2_or_3_Things_I_Know_About_Him A Time to Love and a 1958 Dir.