THE AFRICAN CONTRIBUTION* by Barry Baldwin (University of Calgary)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Poems of Dracontius in Their Vandalic and Visigothic Contexts

The Poems of Dracontius in their Vandalic and Visigothic Contexts Mark Lewis Tizzoni Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. The University of Leeds, Institute for Medieval Studies September 2012 The candidate confinns that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. © 2012 The University of Leeds and Mark Lewis Tizzoni The right of Mark Lewis Tizzoni to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Acknowledgements: There are a great many people to whom I am indebted in the researching and writing of this thesis. Firstly I would like to thank my supervisors: Prof. Ian Wood for his invaluable advice throughout the course of this project and his help with all of the historical and Late Antique aspects of the study and Mr. Ian Moxon, who patiently helped me to work through Dracontius' Latin and prosody, kept me rooted in the Classics, and was always willing to lend an ear. Their encouragement, experience and advice have been not only a great help, but an inspiration. I would also like to thank my advising tutor, Dr. William Flynn for his help in the early stages of the thesis, especially for his advice on liturgy and Latin, and also for helping to secure me the Latin teaching job which allowed me to have a roof over my head. -

Roman Beast Hunts

CHAPTER 34 Roman Beast Hunts Chris Epplett 1 Introduction While gladiatorial combats and chariot races are perhaps the spectacles most commonly asso- ciated with ancient Rome in modern perception, a third type of spectacle, the venatio (beast hunt), was also popular among Romans. Animal spectacles of one kind or another, in fact, were staged over a longer period of time in Roman territory than gladiatorial contests. A variety of sources attest to the popularity of such events in the Roman world. Writers such as Pliny the Elder and Suetonius often mention especially noteworthy spectacles staged in Rome, including venationes. Inscriptions commemorating games staged by wealthy residents of dozens of different communities demonstrate the ubiquity of animal spectacles over the centuries of Roman rule. Artistic evidence, in particular mosaics from North Africa, leave no doubt that venationes were memorable occasions. Staged animal hunts, typically with aristocrats and monarchs as active participants, were a staple of many societies in Asia and Europe for millennia (Allsen 2006; Kyle 2007: 23–37), so it is not surprising that such events also attracted a wide following in ancient Rome. What is relatively rare in terms of the hunts in Rome is that they did not normally include the direct participation of either rulers or the aristocratic elite. Nonetheless, Roman animal spectacles served many of the same ideological and propagandistic functions as those found elsewhere. 2 Origins and Development of the Beast Hunts in Republican Rome When Romans began staging animal spectacles in the third century BCE, they were aware of and influenced by the practices of other cultures in the Mediterranean, most notably A Companion to Sport and Spectacle in Greek and Roman Antiquity, First Edition. -

Metaliteracy & Theatricality in French & Italian Pastoral

THE SHEPHERD‘S SONG: METALITERACY & THEATRICALITY IN FRENCH & ITALIAN PASTORAL by MELINDA A. CRO (Under the Direction of Francis Assaf) ABSTRACT From its inception, pastoral literature has maintained a theatrical quality and an artificiality that not only resonate the escapist nature of the mode but underscore the metaliterary awareness of the author. A popular mode of writing in antiquity and the middle ages, pastoral reached its apex in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries with works like Sannazaro‘s Arcadia, Tasso‘s Aminta, and Honoré d‘Urfé‘s Astrée. This study seeks to examine and elucidate the performative qualities of the pastoral imagination in Italian and French literature during its most popular period of expression, from the thirteenth to the seventeenth century. Selecting representative works including the pastourelles of Jehan Erart and Guiraut Riquier, the two vernacular pastoral works of Boccaccio, Sannazaro‘s Arcadia, Tasso‘s Aminta, and D‘Urfé‘s Astrée, I offer a comparative analysis of pastoral vernacular literature in France and Italy from the medieval period through the seventeenth century. Additionally, I examine the relationship between the theatricality of the works and their setting. Arcadia serves as a space of freedom of expression for the author. I posit that the pastoral realm of Arcadia is directly inspired not by the Greek mountainous region but by the Italian peninsula, thus facilitating the transposition of Arcadia into the author‘s own geographical area. A secondary concern is the motif of death and loss in the pastoral as a repeated commonplace within the mode. Each of these factors contributes to an understanding of the implicit contract that the author endeavors to forge with the reader, exhorting the latter to be active in the reading process. -

Jacopo Sannazaro's Piscatory Eclogues and the Question of Genre

NEW VOICES IN CLASSICAL RECEPTION STUDIES Issue 9 (2014) Jacopo Sannazaro’s Piscatory Eclogues and the Question of Genrei © Erik Fredericksen INTRODUCTION In 1526, Jacopo Sannazaro (1458-1530), the Italian humanist and poet from Naples, published a collection of five Neo-Latin eclogues entitled Eclogae Piscatoriae. He had already authored a hugely influential text in the history of the Western pastoral tradition (the vernacular Arcadia) but, while the Piscatory Eclogues had their admirers and imitators, these poems provoked a debate for many later readers over their authenticity as pastoral poems, due to one essential innovation: Sannazaro exchanged the bucolic countryside and shepherds of classical pastoral for the seashore and its fishermen.ii Through this simple substitution, Sannazaro’s poems question the boundaries of the pastoral genre and— considered along with their critical reception—offer a valuable case study in how a work attains (or does not attain) generic status. In what follows, I argue, against recent criticism, that Sannazaro’s Piscatory Eclogues should be regarded as a pastoral work and suggest that this leads to a better understanding both of the poems themselves and of the dynamics of generic tradition. After examining various features of Sannazaro’s poems, I turn to his models for literature of the sea, both within and outside of pastoral poetry. This is more than a debate over how to label or categorize Sannazaro’s poems; rather, I am arguing that these poems are best understood in relation to the classical tradition of pastoral poetry.iii Thus, after arguing for the collection’s identity as pastoral poems, I will examine the structural relationship of Sannazaro’s eclogue collection to earlier eclogue books (especially Vergil’s), emphasizing how recognition of the poems’ genre helps us appreciate Sannazaro’s sophisticated intertextuality with Vergil and other pastoral predecessors. -

PROTESTÁNS INTÉZMÉNYI KÖNYVTÁRAK MAGYARORSZÁGON 1530-1750 Jegyzékszerű Források

PROTESTÁNS INTÉZMÉNYI KÖNYVTÁRAK MAGYARORSZÁGON 1530-1750 Jegyzékszerű források ORSZÁGOS SZÉCHÉNYI KÖNYVTÁR BUDAPEST 2009 0 PROTESTÁNS INTÉZMÉNYI KÖNYVTÁRAK MAGYARORSZÁGON Libraries of the Protestant Institutions in Hungary ADATTÁR X'VI—XVIII. SZÁZADI SZELLEMI MOZGALMAINK TÖRTÉNE 1 ÉHEZ Documentation of Intellectual Movements History in Hungary from the 16th to the 18th Century 19/2 Sorozatszerkesztő / Ed. by BALÁZS MIHÁLY KESERŰ BÁLINT PROTESTÁNS INTÉZMÉNYI KÖNYVTÁRAK MAGYARORSZÁGON 1530-1750 Jegyzékszerű források Sajtó alá rendezte OLÁH RÓBERT ORSZÁGOS SZÉCHÉNYI KÖNYVTÁR BUDAPEST 2009 Készült a Szegedi Tudományegyetem Régi Magyar Irodalom Tanszéke, a Szegedi Tudományegyetem Könyvtártudományi Tanszéke, és az Országos Széchényi Könyvtár együttműködése keretében In memoriam Oláh Imréné (1961-2008) Lektorálta és szerkesztette MONOK ISTVÁN SZÉKELY JÚLIA Egyes jegyzékek közlésénél munkatárs PAVERCSIK ILONA Technikai szerkesztő DETRE ILDIKÓ ISBN 978-963-200-565-2 HU ISSN 0230-8495 Terjesztés Országos Széchényi Könyvtár H-1827 Budapest, Budavári Palota F épület Király Tímea, [email protected] , tel. +36 — 1 - 22 43 878 TARTALOMJEGYZÉK ELŐSZÓ VII VORWORT X RÖVIDÍTÉSEK XIV KÖNYVJEGYZÉKEK 1 Evangélikus könyvtárak 3 Beszterce 3 Besztercebánya 3 Brassó 4 Eperjes 10 Kassza 11 Késmárk 11 Kisszeben 12 Medgyes 14 Missen 15 Nagyszeben 15 Selmecbánya 16 Sopron 17 Trencsén 19 Református könyvtárak 20 Borberek 20 Debrecen 20 Érsekújvár 225 Gyöngyös 225 Kecskemét 232 Kolozsvár 233 Marosvásárhely 237 Nagybánya 240 Nagyenyed 243 Nagykőrös 245 Nagyszombat 248 Sárospatak 252 Szászváros 330 Szatmár 330 Székelyudvarhely 332 Tarcal 337 Torda 337 V Zabola 337 Zilah 338 Unitárius könyvtárak 338 Kolozsvár 338 Torda 343 Függelék (városi könyvtárak, városi tanácsi könyvtárak, városi intézmények könyvei) 344 Besztercebánya 344 Eperjes 345 Kassa 347 Kőszeg 347 Nagyszeben 348 Trencsén 348 SZEMÉLY- ÉS HELYNÉVMUTATÓ 354 VI ELŐSZÓ Az Adattár a XVI—XVIII. -

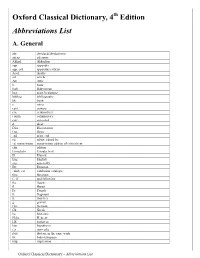

Abbreviations List A

Oxford Classical Dictionary, 4th Edition Abbreviations List A. General abr. abridged/abridgement adesp. adespota Akkad. Akkadian app. appendix app. crit. apparatus criticus Aeol. Aeolic art. article Att. Attic b. born Bab. Babylonian beg. at/nr. beginning bibliog. bibliography bk. book c. circa cent. century cm. centimetre/s comm. commentary corr. corrected d. died Diss. Dissertation Dor. Doric end at/nr. end ed. editor, edited by ed. maior/minor major/minor edition of critical text edn. edition Einzelschr. Einzelschrift El. Elamite Eng. English esp. especially Etr. Etruscan exhib. cat. exhibition catalogue fem. feminine f., ff. and following fig. figure fl. floruit Fr. French fr. fragment ft. foot/feet g. gram/s Ger. German Gk. Greek ha. hectare/s Hebr. Hebrew HS sesterces hyp. hypothesis i.a. inter alia ibid. ibidem, in the same work IE Indo-European imp. impression Oxford Classical Dictionary – Abbreviations List in. inch/es introd. introduction Ion. Ionic It. Italian kg. kilogram/s km. kilometre/s lb. pound/s l., ll. line, lines lit. literally lt. litre/s L. Linnaeus Lat. Latin m. metre/s masc. masculine mi. mile/s ml. millilitre/s mod. modern MS(S) manuscript(s) Mt. Mount n., nn. note, notes n.d. no date neut. neuter no. number ns new series NT New Testament OE Old English Ol. Olympiad ON Old Norse OP Old Persian orig. original (e.g. Ger./Fr. orig. [edn.]) OT Old Testament oz. ounce/s p.a. per annum PIE Proto-Indo-European pl. plate plur. plural pref. preface Proc. Proceedings prol. prologue ps.- pseudo- Pt. part ref. reference repr. -

The House of the Rising Sun: Luminosity and Sacrality from Domus to Ecclesia

Fabio Barry The House of the Rising Sun: Luminosity and Sacrality from Domus to Ecclesia The poem In praise of the younger Justin (566/567 AD) was the last flowering of Latin panegyricepic in Byzantium, written by Corippus, court poet to Justin II (r. 565578). In one passage, the poet offers this ekphrasis of the Emperor’s throneroom in the recently completed Sophia Palace: There is a hall within the upper part of the palace That shines with its own light as though it were open to the clear sky And so gleams with the intense luster of glassy minerals, That, if one may say so, it has no need of the golden sun And it ought really be named the ‘Abode of the Sun’ So pleasing is the sight of the place and still more wondrous in appea- rance1. One commentator has taken these words at face value to mean “a kind of solarium, with walls and perhaps roof of glass.”2 Instead, the poet means a chamber sheathed in glass mosa- ic (“vitrei… metalli”), indubitably vaulted not glazed, and abounding in such gleaming reflec- tions that the room seemed to illuminate itself. It was a throneroom worthy of the Sun himself and the emperor Justin, we are to understand, is that Sun. This interpretation is more than confirmed by the permutations on the theme that pervade the rest of the poem: Justin acce- ded to the throne at dawn and light filled the palace at his acclamation; his father Justinian (fig. 1) was “the light of the city and the world”; Justin’s royal limbs emit light; the “imperial palace with its officials is like Olympus. -

Vandalia: Identity, Policy, and Nation-Building in Late-Antique North Africa

VANDALIA: IDENTITY, POLICY, AND NATION-BUILDING IN LATE-ANTIQUE NORTH AFRICA BY EUGENE JOHAN JANSSEN PARKER A thesis submitted to the Victoria University of Wellington in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Victoria University of Wellington 2018 Abstract In 534, after the conquest of the Vandal kingdom, Procopius tells us that the emperor Justinian deported all remaining Vandals to serve on the Persian frontier. But a hundred years of Vandal rule bred cultural ambiguities in Africa, and the changes in identity that occurred during the Vandal century persisted long after the Vandals had been shipped off to the East: Byzantine and Arabic writers alike shared the conviction that the Africans had, by the sixth and seventh centuries, become something other than Roman. This thesis surveys the available evidence for cultural transformation and merger of identities between the two principal peoples of Vandal Africa, the Vandals and the Romano-Africans, to determine the origins of those changes in identity, and how the people of Africa came to be different enough from Romans for ancient writers to pass such comment. It examines the visible conversation around ethnicity in late-antique Africa to determine what the defining social signifiers of Vandal and Romano-African identity were during the Vandal century, and how they changed over time. Likewise, it explores the evidence for deliberate attempts by the Vandal state to foster national unity and identity among their subjects, and in particular the role that religion and the African Arian Church played in furthering these strategies for national unity. Finally, it traces into the Byzantine period the after-effects of changes that occurred in Africa during the Vandal period, discussing how shifts in what it meant to be Roman or Vandal in Africa under Vandal rule shaped the province's history and character after its incorporation into the Eastern Empire. -

Diplomarbeit

DIPLOMARBEIT Titel der Diplomarbeit „Quae regna potentia vidi, exposui lustranda oculis – Paratexte in Herbersteins Moscovia“ verfasst von Cornelia Permesser angestrebter akademischer Grad Magistra der Philosophie (Mag.phil.) Wien, 2015 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 190 338 362 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Lehramtsstudium UF >Latein< UF >Russisch< Betreut von: ao.Univ.-Prof. Mag. Dr. Elisabeth Klecker 2 … ego cum a Caesare Maximiliano legatus in Moscoviam missus eram … … Oratores ad se ordine vocat, Leonharde Sigismunde dicens venisti a Magno Domino, ad Magnum Dominum, fecisti magnum iter, vidisti gratiam nostram, et serenos oculos nostros, bibe & ebibe, & bene ede usque ad saturitatem, deinde quiesces, ut tandem ad Dominum tuum redire possis. Sigmund von Herberstein Rerum Moscoviticarum Commentarii 3 4 Inhaltsverzeichnis 1 Danksagung …............................................................................................................... 7 2 Einleitung ….................................................................................................................. 8 3 Das Leben des Sigmund von Herberstein i…................................................................. 9 4 Ausgaben der Rerum Moscoviticarum Commentarii ….............................................. 16 4.1 Die lateinische Erstausgabe …............................................................................... 17 4.2 Die zweite lateinische Ausgabe …......................................................................... 22 4.3 Die dritte lateinische -

The Date of the Bucolic Poet Martius Valerius

Edinburgh Research Explorer The date of the bucolic poet Martius Valerius Citation for published version: Stover, J 2017, 'The date of the bucolic poet Martius Valerius', Journal of Roman Studies, vol. 107, pp. 301- 335. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0075435817000806 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.1017/S0075435817000806 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Peer reviewed version Published In: Journal of Roman Studies Publisher Rights Statement: This article has been published in a revised form in The Journal of Roman Studies, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0075435817000806. This version is free to view and download for private research and study only. Not for re-distribution, re-sale or use in derivative works. © The Author 2017. Published by The Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies. General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 29. Sep. 2021 THE DATE OF THE BUCOLIC POET MARTIUS VALERIUS ergo, parve liber, patres i posce benignos affectumque probent iudiciumque tegant. Martius Valerius, prologus 21-2 I ‘AN AS-YET ENTIRELY UNKNOWN WORK OF ANTIQUITY IN LATIN VERSE’ ? Bucolic poetry is hard to date. -

Aetna ; Would Have Been Impossible in Catullus, Not Indeed in Isolated Speci- Mens, but in Consecutive Lines

HENRY FROWDE, M.A. PUBLISHER TO THE UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD LONDON, EDINItUKGII NEW YORK AETNA A CRITICAL RECENSION OF THE TEXT, BASED ON A NEW EXAMINATION OF MSS. WITH PROLEGOMENA, TRANSLATION, TEXTUAL AND EXEGETICAL COMMENTARY, EXCURSUS, AND COMPLETE INDEX OF THE WORDS ROBINSON ELLIS, M.A., LL.D. CORPUS PROFESSOR OF THE LATIN LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE HONORARY FELLOW OF TRINITY COLLEGE OXFORD AT THE CLARENDON PRESS 1901 OXFORD 1 RINTED AT THE CLARENDON PRESS nv HORACE HART, M.A. IRINTP.R TO THE UNIVERSITY TO THE REVEREND THOMAS FOWLER D.D. PRESIDENT OF THE COLLEGE OF CORFL'5 CHRISTI THIS VOLUME IS DEDICATED IN RECOGNITION OI" MANY ACTS OF FRIENDSHIP CONTINIED THROUGH A PERIOD OF MORE THAN FORTY YEARS Digitized by tine Internet Archive in 2008 with funding from IVIicrosoft Corporation C^-v http://www.archive.org/details/aetna OOelliuoft PREFACE This volume does not aspire to do more than adumbrate the present state of criticism on the many problems which the difficult poem Aetna raises. When, in 1867, Munro gave to the world for the first time a complete collation of the one unimpeachable source for constituting the text, the tenth-century Cambridge MS. Kk v. 34, he was really laying the basis of a more exact criticism ; for though the value of C was well known, and its readings had been used by Moriz Haupt in his various papers and dissertations on Aetna, no complete con- spectus of the MS. was before the public till the great Cambridge scholar exhibited it in its entirety. Little was done for the further illustration of the poem till 18S0 when Bahrcns edited the poem as part of the Appendix Vergiliana in the second volume of his Poetae Latini Minores. -

Latin Literature by JW Mackail</H1>

Latin Literature by J. W. Mackail Latin Literature by J. W. Mackail Produced by Distributed Proofreaders LATIN LITERATURE BY J. W. MACKAIL, Sometime Fellow of Balliol College, Oxford A history of Latin Literature was to have been written for this series of Manuals by the late Professor William Sellar. After his death I was asked, as one of his old pupils, to carry out the work which he had undertaken; and this book is now offered as a last tribute to the memory of my dear friend and master. J. W. M. CONTENTS. I. THE REPUBLIC. page 1 / 332 I. ORIGINS OF LATIN LITERATURE: EARLY EPIC AND TRAGEDY. Andronicus--Naevius--Ennius--Pacuvius--Accius II. COMEDY: PLAUTUS AND TERENCE. III. EARLY PROSE: THE SATURA, OR MIXED MODE. The Early Jurists, Annalists, and Orators--Cato--The Scipionic Circle--Lucilius IV. LUCRETIUS. V. LYRIC POETRY: CATULLUS. Cinna and Calvus--Catullus VI. CICERO. VII. PROSE OF THE CICERONIAN AGE. Julius Caesar--The Continuators of the Commentaries-- Sallust--Nepos--Varro--Publilius Syrus II. THE AUGUSTAN AGE. I. VIRGIL. II. HORACE. III. PROPERTIUS AND THE ELEGISTS. Augustan Tragedy--Gallus--Propertius--Tibullus IV. OVID. Sulpicia--Ovid V. LIVY. VI. THE LESSER AUGUSTANS. Manilius--Phaedrus--Velleius--Paterculus--Celsus-- page 2 / 332 Vitruvius--The Elder Seneca III. THE EMPIRE. I. THE ROME OF NERO. The Younger Seneca--Lucan--Persius--Quintus Curtius --Columella--Calpurnius--Petronius II. THE SILVER AGE. Statius--Valerius Flaccus--Silius Italicus--Martial--The Elder Pliny--Quintilian III. TACITUS. IV. JUVENAL, THE YOUNGER PLINY, SUETONIUS: DECAY OF CLASSICAL LATIN. V. THE ELOCUTIO NOVELLA. Fronto--Apuleius--The Pervigilium Veneris VI.