Contrasting Images of Power and Poppy in the Provinces of Balkh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DOSTUM: AFGHANISTAN’S EMBATTLED WARLORD by Brian Glyn Williams

VOLUME VI, ISSUE 8 APRIL 17, 2008 IN THIS ISSUE: DOSTUM: AFGHANISTAN’S EMBATTLED WARLORD By Brian Glyn Williams....................................................................................1 SINO-PAKISTANI DEFENSE RELATIONS AND THE WAR ON TERRORISM By Tariq Mahmud Ashraf................................................................................4 CAPABILITIES AND RESTRAINTS IN TURKEY’S COUNTER-TERRORISM POLICY By Gareth Jenkins...........................................................................................7 AL-QAEDA’S PALESTINIAN INROADS Abdul Rashid Dostum By Fadhil Ali....................................................................................................10 Terrorism Monitor is a publication of The Jamestown Foundation. Dostum: Afghanistan’s Embattled Warlord The Terrorism Monitor is designed to be read by policy- By Brian Glyn Williams makers and other specialists yet be accessible to the general While the resurgence of the Taliban is the focus of interest in the Pashtun south public. The opinions expressed within are solely those of the of Afghanistan, the year started with a different story in the north that many are authors and do not necessarily depicting as one of the greatest challenges to the Karzai government. Namely the reflect those of The Jamestown surreal confrontation between General Abdul Rashid Dostum, the larger-than- Foundation. life Uzbek jang salar (warlord)—who was once described as “one of the best equipped and armed warlords ever”—and one of his former aides [1]. In a move that many critics of the situation in Afghanistan saw as epitomizing Unauthorized reproduction or the Karzai government’s cravenness in dealing with brutal warlords, the Afghan redistribution of this or any government backed away from arresting Dostum after he beat up and kidnapped Jamestown publication is strictly a former election manager and spokesman in Kabul on February 3 (IHT, February prohibited by law. -

Hekmatyar Taken Off UN Sanctions List: Paving the Way for His Return – and Hezb-E Islami’S Reunification?

Hekmatyar taken off UN sanctions list: Paving the way for his return – and Hezb-e Islami’s reunification? Author : Thomas Ruttig Published: 11 February 2017 Downloaded: 4 September 2018 Download URL: https://www.afghanistan-analysts.org/hekmatyar-taken-off-un-sanctions-list-paving-the-way-for-his-return-and-hezb-e- islamis-reunification/?format=pdf The United Nations has lifted the sanctions against Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, the leader of the Islamic Party of Afghanistan. This was the next step in the implementation of the peace agreement signed by the Afghan government and Hezb in September 2016. It paves the way for the return of the former mujahedin leader, one of the most contentious figures in recent Afghan history – a hero of the jihad according to supporters, a war criminal according to detractors. AAN’s co-director Thomas Ruttig follows up on earlier AAN analysis of the peace agreement, looks at what happens next and possible implications for Hekmatyar’s party (with input from Kate Clark, Fazal Muzhary and Ehsan Qaane). Over four months after the peace deal between the Afghan government and Hezb-e Islami was signed by President Ashraf Ghani and Hezb leader (amir) Gulbuddin Hekmatyar (who was not personally present but brought in via video link), the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) has taken Hekmatyar off its sanctions list. A press release about this measure was published on 3 February 2017 (see the full text in the annex to this dispatch). Without it, the government would have been obliged to detain Hekmatyar if he came to Kabul openly. In the September 2016 agreement with Hezb-e Islami Afghanistan (HIA, Islamic Party of Afghanistan), the Afghan government had committed to take measures that would remove “all sanctions” against the leadership and members of Hezb as a prerequisite for its implementation. -

Algemeen Ambtsbericht Afghanistan Juli 2010

Algemeen ambtsbericht Afghanistan Juli 2010 Directie Consulaire Zaken en Migratiebeleid Afdeling Asiel, Hervestiging en Terugkeer Inhoudsopgave Pagina 1 Inleiding 4 2 Landeninformatie 5 2.1 Basisgegevens 5 2.1.1 Land en volk 5 2.1.2 Geschiedenis 9 2.1.3 Staatsinrichting 13 2.2 Politieke ontwikkelingen 18 2.3 Afghaanse veiligheidsorganisaties 22 2.3.1 Afghan National Army 22 2.3.2 Afghan National Police 23 2.3.3 Veiligheidsdienst NDS 26 2.3.4 Burgermilities 27 2.4 Internationale militaire presentie 28 2.5 Machtsfactoren 30 2.5.1 Taliban 32 2.5.2 Jalaluddin Haqqani 34 2.5.3 Hezb-i-Islami 35 2.5.4 Ontwapening, demobilisatie en re-integratie 36 2.6 Veiligheidssituatie 37 2.6.1 Bescherming tegen geweld 38 2.6.2 Doelwitten 38 2.6.3 Burgerslachtoffers 39 2.6.4 Gedwongen rekrutering en ronseling 41 2.6.5 Regionale verdeling veiligheidsincidenten 41 3 Mensenrechten 46 3.1 Juridische context 46 3.1.1 Verdragen en protocollen 46 3.1.2 Nationale wetgeving 46 3.2 Toezicht 48 3.2.1 Mensenrechtencommissie AIHCR 49 3.2.2 Transitional Justice 50 3.3 Naleving en schendingen 53 3.3.1 Vrijheid van meningsuiting 53 3.3.2 Vrijheid van vereniging en vergadering 56 3.3.3 Vrijheid van godsdienst en overtuiging 56 3.3.4 Bewegingsvrijheid en documenten 59 3.3.5 Rechtsgang 62 3.3.6 Arrestaties en detentie 64 3.3.7 Foltering, mishandeling en bedreiging 66 3.3.8 Ontvoeringen 67 3.3.9 Buitengerechtelijke executies en moorden 67 3.3.10 Doodstraf 68 3.4 Positie van specifieke groepen 69 3.4.1 Politieke opposanten en mensenrechtenactivisten 69 3.4.2 Etnische groepen 70 -

Special Report No

SPECIAL REPORT NO. 444 | MARCH 2019 UNITED STATES INSTITUTE OF PEACE www.usip.org How Peace Was Made: An Inside Account of Talks between the Afghan Government and Hezb-e Islami By Qaseem Ludin Contents Background ...................................3 Talks Begin ................................... 5 Internal Consensus and Divisions .................................7 Components of the Peace Deal ....................................8 Sealing the Deal ......................... 12 Implementation of the Agreement ............................ 13 Lessons for Negotiations with the Taliban ........................... 14 Gulbuddin Hekmatyar addresses supporters in Jalalabad, Afghanistan, in March 2018. (Photo by Ghulamullah Habibi/EPA-EFE/ Shutterstock) Summary • For more than four decades, Afghan- • Peacemaking is a difficult process, the challenges and divisions that istan has been in a state of war and but often the most difficult part is had to be overcome in order to violent conflict that has destroyed how to start peace talks. Thus, the make the September 2016 peace much of the country’s physical and experience of negotiating peace agreement possible. social infrastructure and prevent- between the Afghan government • After the peace accord with ed the formation of a state stable and the Hezb-e Islami insurgent Hezb-e Islami, Afghans have an- enough to establish law and order. group offers unique insights on other historic chance to bring an • Although several internal and exter- peacemaking in the modern era. end to years of conflict with the nal factors contributed to the conflict • This report, based on the author’s Taliban. The Afghan government’s and its current political and security experience working as a negoti- negotiations with Hezb-e Islami environment, a key factor has been ator during talks between the Af- provide important lessons that can weak Afghan leadership, exacerbat- ghan government and Hezb-e Isla- be applied to future peace negoti- ed by political frictions among elites. -

The Network Politics of International Statebuilding: Intervention and Statehood in Post-2001 Afghanistan

The Network Politics of International Statebuilding: Intervention and Statehood in Post-2001 Afghanistan Submitted by Timor Sharan to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Politics In October 2013 This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. Signature: ………………………………………………………….. 1 ABSTRACT This thesis focuses on international intervention and statebuilding in post- 2001 Afghanistan. It offers an alternative lens, a network lens, to understand the complexity of internationally sponsored state re-building and transformation. It therefore analyses how political power is assembled and flows through political networks in statebuilding, with an eye to the hitherto ignored endogenous political networks. The empirical chapters investigate the role and power dynamics of Afghan political network in re-assembling and transforming the post-2001 state once a political settlement is reached; how everyday political network practices shape the nature of statehood and governance; and subsequently how these power dynamics and practices contribute towards political order/violence and stability/instability. This thesis challenges the dominant wisdom that peacebuilding is a process of democratisation or institutionalisation, showing how intervention has unintentionally produced the democratic façade of a state, underpinning by informal power structures of Afghan politics. The post-2001 intervention has fashioned a ‘network state’ where the state and political networks have become indistinguishable from one another: the empowered network masquerade as the state. -

1213E Resilient Oligopoly IP Dec 2012 for Design 29 Dec.Indd

Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit Case Study Series The Resilient Oligopoly: A Political-Economy of Northern Afghanistan 2001 and Onwards Antonio Giustozzi December 2012 Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit Research for a Better Afghanistan This page has been left blank to facilitate double-sided printing Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit Issues Paper The Resilient Oligopoly: A Political-Economy of Northern Afghanistan 2001 and onwards Dr Antonio Giustozzi Funding for this research was provided by the December 2012 the Embassy of Finland in Kabul, Afghanistan Editing and Layout: Sradda Thapa Cover Photographs: (Top to bottom): Bazaar Day in Jowzjan; Marketplace in Shiberghan; New recruits at the Kabul Military Training Center; Mazar-Hayratan highway (all by Subel Bhandari) AREU Publication Code: 1213E AREU Publication Type: Issues Paper © 2012 Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit. Some rights reserved. This publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted only for non-commercial purposes and with written credit to AREU and the author. Where this publication is reproduced, stored or transmitted electronically, a link to AREU’s website (www.areu.org.af) should be provided. Any use of this publication falling outside of these permissions requires prior written permission of the publisher, the Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit. Permission can be sought by emailing [email protected] or by calling +93 (0) 799 608 548. Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit About the Author Dr Antonio Giustozzi is an independent researcher who took his PhD at the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE) and is currently associated with King’s College London, Department of War Studies. -

Pajhwok Afghan News (PAN) Weekly Election Coverage Newsletter, Aug 27-Sep 2

Pajhwok Afghan News (PAN) Weekly Election Coverage Newsletter, Aug 27-Sep 2 Wishing anonymity, an official at the Independent Election Commission (IEC) said representatives of the commission, UN and Change and Continuity team were in discussions on resuming the process. A Pajhwok Afghan News journalist reported at around 10:30am that representatives of the Reform and Unanimity team could not be seen on IEC premises. But UN, IEC and Ahmadzai representatives are yet to comment on the latest development. A day earlier, the Reform and Unanimity team, led by presidential candidate Dr. Abdullah Abdullah, warned of boycotting the ongoing vote audit if its technical demands were not meet. Fazal Ahmad Manawi, a member of Dr. Abdullah’s camp, Afghan leaders need hard compromise: Obama said they would not be part of the ongoing ballot audit By Lalit K Jha Aug 27, 2014 - 10:51 anymore. He alleged the process had been politically hijacked. WASHINGTON (PAN): Amidst a lingering dispute over He said the Reform and Unanimity team had some the auditing of votes, US President Barack Obama on reservations about the vote-invalidating procedure. The Tuesday said the leaders of Afghanistan needed to make process had been set in motion at the time when the two hard compromise for the sake of their country's future and sides had not agreed on invalidation benchmarks, he security. claimed. Though Obama did not name anyone during his public Around 72.6 percent of votes have been audited so far as speech in North Carolina, yet his remarks were directly part of the scrutiny that started on July 17 after the aimed at the two presidential candidates – Dr Abdullah electoral process hit an impasse due to severe differences Abdullah and Dr. -

Downloaded for Personal Non‐Commercial Research Or Study, Without Prior Permission Or Charge

Hakimi, Aziz Ahmed (2015) Fighting for patronage: American counterinsurgency and the Afghan local police. PhD thesis. SOAS, University of London. Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non‐commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this thesis, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", name of the School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination. Fighting for Patronage: American counterinsurgency and the Afghan Local Police AZIZ AHMED HAKIMI Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Development Studies School of Oriental and African Studies University of London 2015 1 Abstract This thesis examines the emergence and evolution of the Afghan Local Police (ALP), a pro-government militia supported by the US military as an entry point for exploring the fluid security and political terrain of post-2001 Afghanistan. The study reveals how the ALP emerged as a compromise between the US ambition to scale up the use of local militias and the Afghan president’s attempts to control the local armed groups and the flow of patronage that the US support to these groups represented. -

Counterinsurgency, Local Militias, and Statebuilding in Afghanistan

[PEACEW RKS [ COUNTERINSURGENCY, LOCAL MILITIAS, AND STATEBUILDING IN AFGHANISTAN Jonathan Goodhand and Aziz Hakimi ABOUT THE REPORT Much international effort and funding have focused on building and bureaucratizing the means of violence in Afghanistan. At the same time, parallel government and NATO experiments have armed local defense forces, including local militias, under the Afghan Local Police (ALP) program to fight the insurgency and provide security at the local level. This report—which is based on a year’s research in Kabul and the provinces of Wardak, Baghlan, and Kunduz—seeks to understand the role and impact of the ALP on security and political dynamics in the context of ongoing counterinsurgency and stabilization operations and the projected drawdown of international troops in 2014 . ABOUT THE AUTHORS Jonathan Goodhand is a professor of conflict and development studies in the Development Studies department at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) at the University of London. His research interests include the political economy of aid, conflict, and postwar reconstruction, with a particular focus on Afghanistan and Sri Lanka. Aziz Hakimi is a PhD candidate at SOAS. His dissertation focuses on the ALP in relation to Afghan statebuilding. Cover photo: Afghan Local Police candidates, Daykundi Province, by Petty Officer 2nd Class David Brandenburg, supplied by DVIDS The views expressed in this report are those of the authors alone. They do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Institute of Peace. United States Institute of Peace 2301 Constitution Ave., NW Washington, DC 20037 Phone: 202.457.1700 Fax: 202.429.6063 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.usip.org Peaceworks No. -

Warlords, Tribal Leaders and Insurgents in Afghanistan Conrad Schetter and Rainer Glassner*

THEMENSCHWERPUNKT | Local Configurations of Violence: Warlords, Tribal Leaders and Insurgents in Afghanistan Conrad Schetter and Rainer Glassner* Abstract: On the backdrop of a weak central government the article examines three types of local configurations of violence in Afghanistan. The concentration of power at the local level is so strong, that even the core institutions of the state are under control of local interests. Thus, in Kandahar province powerful tribal individuals control the means of violence. The combination of insurgency, drug networks and tribal structures has encouraged the emergence of strong warlords and the Taliban in Kandahar. In contrast to Kandahar, Kunduz province shows myriads of minifiefdoms as well as localized ‘rules of law’, or ‘rules of the gun’, which result in fragmented warlordism. Finally, in Paktia province tribal identities are the most important points of reference. The Pashtun tribal code of law and behavior is the ‘rule of the game’, and Paktia tribes settle their conflicts in tribal gatherings by discussion until a consensus is reached. Keywords: Afghanistan, insurgents, tribes, warlords Afghanistan, Aufständische, Stämme, Warlords 1. Introduction of Illegal Armed Groups (DIAG) from 2005 to 2011, failed to disband the ‘clientelistic’ structures of commanders and olicymakers, journalists and researchers time and their militiamen (Giustozzi 2008). In most cases, influential again stress the lack of physical security in Afghanistan commanders were able to preserve their power by assuming by circumscribing it with the term ‘warlordism’ (see formal positions in the government or by transforming their PGiustozzi 2009a). Since the intervention in 2002, virtually no militias into regular army or police units. -

Understanding Ethnic-Electoral Dynamics: How Ethnic Politics Affect Electoral Laws and Election Outcomes in Afghanistan

MOBASHER 4/18/2016 3:11 PM UNDERSTANDING ETHNIC-ELECTORAL DYNAMICS: HOW ETHNIC POLITICS AFFECT ELECTORAL LAWS AND ELECTION OUTCOMES IN AFGHANISTAN *Mohammad Bashir Mobasher After the fall of the Taliban in 2001, Afghanistan began transitioning toward democracy. The democratization, which began with the Bonn Agreement, was very promising for all ethnic groups in Afghanistan. The Bonn Agreement provided that Afghanistan must establish “broad based, gender sensitive, multi- ethnic and fully representative government.”1 As a part of this agreement, Afghanistan adopted a new Constitution in 2004, which established elections as the foundation for representative government and guaranteed that the elections be inclusive, fair, and representative of all groups and regions. Despite this progress in the laws, Afghanistan has not been able to reduce ethnic tensions. In fact, this article shows that ethnic tensions tend to intensify during elections, a result that belies the vision of the Bonn Agreement. After presenting a statistical and qualitative analysis of voting practices across three presidential elections and 26 provinces, this article makes several observations about the role of ethnicity in Afghan presidential elections. These observations are: (1) people of an ethnic community are more likely to vote for a candidate of their own ethnic group; (2) voters from one ethnic group are likely to vote for a candidate from another ethnic group only when they do not have a candidate of their own; (3) cross ethnic voting is more likely to occur in blocs and in exchange for patronage to the elites of voting groups; and (4) candidates and ethno-political elites tend to prioritize their electoral campaigns by ethnic mobilization, manipulation of laws and political bargains rather than by policy development in order to generate votes. -

Paktya Provincial Profile

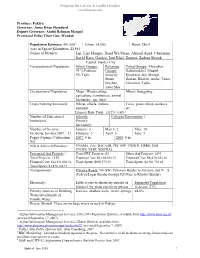

Program for Culture & Conflict Studies [email protected] Province: Paktya Governor: Juma Khan Hamdard Deputy Governor: Abdul Rahman Mangal Provincial Police Chief Gen. Wardak Population Estimate: 401,3001 Urban: 14,900 Rural: 386.4 Area in Square Kilometers: 22,915 Names of Districts: Jaji, Lija Mangal, Dand Wa Patan, Ahmad Abad, Chamkani, Sayid Kara, Gardez, Jani Khel, Zormat, Zadran Shwak Capital: Gardez City Composition of Population: Ethnic Groups: Religious Tribal Groups: Ahmadzai, 91 % Pashtun, Groups: Suleimankhel, Muqbil, 9% Tajik majority Khostwal, Jaji, Mangal, Sunni Zadran, Kharoti, Andar, Tanai, Muslim, Utmanzai, Tajiks some Shia Occupation of Population Major: Wood cutting, Minor: Smuggling agriculture, remittances, animal husbandry, day labor Crops/Farming/Livestock: Wheat, alfalfa, melons, Cows, goats, sheep, donkeys, almonds etc. Literacy Rate Total: 10.2%2-16%3 Number of Educational Schools: Colleges/Universities: 1 Institutions: Primary: Secondary: Number of Security January: 3 March: 2 May: 10 Incidents, Jan-Jun 2007:4 21 February: 3 April: 0 June: 3 Poppy (Opium) Cultivation: 2007: 0 ha 2008: 0 ha Nil NGOs Active in Province: UNAMA, Care, DACAAR, PIN, NSP, UNHCR, MRRD, IOM, UNOPS, NEEP, NEEPRAL Provincial Aid Projects:5 Total PRT Projects: 62 Other Aid Projects: 1093 Total Projects: 1155 Planned Cost: $4,104,580.35 Planned Cost: $8,436,422.61 Planned Cost: $12,541,002.96 Total Spent: $850,578.35 Total Spent: $2,984,755.82 Total Spent: $3,835,334.17 Transportation: Primary Roads: NE-SW (Pakistani Border to Zormat), and N – S (Paktya/Logar Border through KG Pass to Khowst Border) Electricity: Little access to electricity outside of Estimated Population Gardez City, most electricity private w/access: 33% Primary Sources of Drinking Karezes, shallow wells, rivers, springs 48.6% Water/Availability of Potable Water: Rivers: Shamal.