Choreographic Objects: Stifters Dinge

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Interpretive Gesture: Heiner Goebbels and the Imagination of the Public Sphere

THE INTERPRETIVE GESTURE: HEINER GOEBBELS AND THE IMAGINATION OF THE PUBLIC SPHERE Luke Matthews Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degree Master of Arts (English and Theatre Studies) Thesis (by Research) February 2019 English and Theatre Studies Program School of Culture and Communications Faculty of Arts The University of Melbourne ABSTRACT Heiner Goebbels’s Stifters Dinge and When the Mountain Changed Its Clothing are examples of “postdramatic” theatre works that engage with the political by seeking to challenge socially ingrained habits of perception rather than by presenting traditional, literary-based theatre of political didacticism or agitation. Goebbels claims to work toward a “non-hierarchical” theatre in the contexts of his arrangement of the various theatrical elements, in fostering collaborative working processes between the artists involved, and in the creation of audience-artist relationships. I argue that, in doing so, he follows a familiar theoretical trajectory that employs the theatre as a convenient metaphor for the public sphere. Two broad traditions exist concerning this connection between theatre and publicness: first, a line of thought that sets theatre against the rational community of equals; and, second, an opposing tradition which looks in hope to theatre for the possibility of a participatory democracy. In situating Goebbels’s practice within this second tradition, I moreover argue that the metaphor of the theatrical public sphere may also be understood in terms of a negotiation between Kantian sublimity and the notion of the beautiful. 1 DECLARATION I hereby certify that this thesis comprises only my original work towards the Masters by Research degree and that due acknowledgement has been made in the text to all other material used. -

Heiner Goebbels

444 HUHIGNY rtSi:.".c) IvAL Le'Auomi;fe rAiu5 s CONCEPTION. MUSIQUE ET MISE EN SCÈNE Heiner Goebbels SPECTACLE MUSICAL AVEC l'Ensemble Modern 26> 29 NOVEMBRE 1997 Document de communication du Festival d'Automne à Paris - tous droits réservés MC93 Bobigny ProductionDas TAT, Francfort / Hebbel Theater, Noir sur blanc balisant pour ainsi dire l'espace par ces et le Festival d'Automne à Paris Berlin / Kaaitheater, Bruxelles, 1996. inscriptions acoustiques. Ces espaces sonores si En collaboration avec l'Ensemble Modern, Francfort. vivants (mais aussi éphémères) sont le produit Depuis une dizaine d'années, le compositeur présentent Composé en 1995/96, création le 14 mars 1996 au d'un jeu d'ensemble alors que les textes cités de Heiner Goebbels, résidant à Francfort, travaille Bockenheimer Depot de Francfort. Blanchot, Eliot et Poe, dits par l'un ou l'autre en collaboration avec l'Ensemble Modern qui a Présentation en France : MC 93 Bobigny et membre de l'Ensemble, chacun dans sa langue créé plusieurs de ses oeuvres. Le projet de Festival d'Automne à Paris maternelle, sont livrés de manière libre, HEINER GOEBBELS théâtre musical Schwarz Weiss pour le Avec le concours de l'Ambassade de France en ouf circulant comme des blocs erratiques. Ces textes Allemagne Theater am Turm de Francfort, en 1996, est le Schwarz auf Weiss fruit de plusieurs mois de travail avec cet traitent du caractère transitoire des choses, de La Maison de la Culture de Seine-Saint-Dents/MC93 la solitude de l'écriture, de la fragilité de la voix Noir sur blanc Bobigny est subventionnée par le Ministère de la ensemble. -

HEINER GOEBBELS Stifters Dinge

THÉÂTRE VIDY-LAUSANNE AV. E.-H. JAQUES-DALCROZE 5 CH-1007 LAUSANNE Direction production and touring Caroline Barneaud Mail: [email protected] In charge of the project Elizabeth Gay Mail: [email protected] T +41 (0)21 619 45 22 P +41 (0)79 278 05 93 Skype: elizabethgay HEINER GOEBBELS Stifters Dinge Stifters Dinge © Mario Del Curto HEINER GOEBBELS STIFTERS DINGE 2 Création DISTRIBUTION à Vidy Conception, music and direction : Heiner Goebbels Set design, light and video : Klaus Grünberg Musical collaboration/programming : Hubert Machnik Sound design : Willi Bopp Artistic collaboration : Matthias Mohr TEAM TOUR Stage Manager : Nicolas Pilet Light technician : Roby Carruba Mattias Bovard Video : Jérôme Vernez Stéphane Janvier René Liebert Robotic : Thierry Kaltenrieder Sound design : Willi Bopp Sound Ludovic Guglielmazzi Musical supervision : Matthias Mohr Assistant stage manager : Jean-Daniel Buri Fabio Gaggetta Tour Manager : Sylvain Didry Production : Théâtre de Vidy Coproduction : spielzeit’europa – Berliner Festspiele – Grand Théâtre de la Ville de Luxembourg – schauspielfrankfurt – T&M-Théâtre de Gennevilliers/CDN – Pour-cent culturel Migros – Teatro Stabile di Torino Corealisation : Artangel London With the support of : Pro Helvetia - Fondation suisse pour la culture Duration : 1h10 Creation on September 13th 2007 at Théâtre de Vidy HEINER GOEBBELS STIFTERS DINGE 3 PRÉSENTATION ”Stifter’s Things” is a composition for five pianos with no pianists, a play with no actors, a perfor- mance without performers – one might say a no-man show. First and foremost, it is an invitation to audiences to enter a fascinating space full of sounds and images, an invitation to see and hear. It revolves around awareness of things, things that in the theatre are often part of the set or act as props and play a merely illustrative role. -

Hcmf.Co.Uk Box Office 01484 430528 #Hcmf2019 Friday 15 – Sunday 24

Friday 15 – Sunday 24 November 2019 hcmf.co.uk Box Office 01484 430528 #hcmf2019 UK UK PREMIERE FESTIVAL DIARY W WORLD PREMIERE DATE NO EVENT TIME VENUE Fri 15 Nov Exhibition Launch: Claudia Molitor W 4pm Market Gallery, Temporary Contemporary, Queensgate Market edges ensemble: Grapefruit 5pm Temporary Contemporary, Queensgate Market Pre-Concert Talk: Naomi Pinnock + Ann Cleare 6pm St Paul’s Hall 1 Sonar Quartett + Juliet Fraser W UK 7pm St Paul’s Hall 2 The Riot Ensemble: Ann Cleare Portrait UK 9.30pm Huddersfield Town Hall Hanna Hartman: Solo Works UK 11.15pm Bates Mill Photographic Studio Sat 16 Nov Mini Pop-Up Art School 10am - 12pm Temporary Contemporary Queensgate Market Meet the Composer: Hanna Hartman 11am Phipps Hall 3 Ellen Arkbro + Marcus Pal W 1pm St Paul’s Hall 4 Iced Bodies UK 4pm Bates Mill Blending Shed 5 The Riot Ensemble W UK 7pm St Paul’s Hall 6 Decay / Sofia Jernberg 9.45pm Bates Mill Photographic Studio Sun 17 Nov Meet the Composer: Heiner Goebbels 11am Phipps Hall 7 Norrbotten NEO UK 1pm St Paul’s Hall 8 Hanna Hartman: Hurricane Season W 5pm Bates Mill Photographic Studio 9 Jenny Hval: The Practice Of Love 7pm Bates Mill Blending Shed 10 Heiner Goebbels + Gianni Gebbia 9pm St Paul’s Hall Isidore Isou: Juvenal Symphony No 4 UK 11pm Huddersfield Town Hall Mon 18 Nov Launch Event: cageconcert 10am - 5pm Richard Steinitz Building Atrium Installation: Georgia Rodgers W 11am - 5pm SPIRAL Studio, Richard Steinitz Building Group Chat W 11.30am Richard Steinitz Building Atrium John Butcher W 12pm Phipps Hall The Hermes Experiment -

25 Years of Ars Electronica

Literature: Winners in the film section – Computer Animation – Visual Effects Literature: Literature : Literature: Literature (2) : Literature: Literature (2) : Blick, Stimme und (k)ein Körper – Der Einsatz 1987: John Lasseter, Mario Canali, Rolf Herken Cyber Society – Mythos und Realität der Maschinen, Medien, Performances – Theater an Future cinema !! / Jeffrey Shaw, Peter Weibel Ed. Gary Hill / Selected Works Soundcultures – Über elektronische und digitale Kunst als Sendung – Von der Telegrafie zum der elektronischen Medien im Theater und in 1988: John Lasseter, Peter Weibel, Mario Canali and Honorary Mentions (right) Informationsgesellschaft / Achim Bühl der Schnittstelle zu digitalen Welten / Kunst und Video / Bettina Gruber, Maria Vedder Intermedialität – Das System Peter Greenaway Musik / Ed. Marcus S. Kleiner, A. Szepanski 25 years of ars electronica Internet / Dieter Daniels VideoKunst / Gerda Lampalzer interaktiven Installationen / Mona Sarkis Tausend Welten – Die Auflösung der Gesellschaft Martina Leeker (Ed.) Yvonne Spielmann Resonanzen – Aspekte der Klangkunst / 1989: Joan Staveley, Amkraut & Girard, Simon Wachsmuth, Zdzislaw Pokutycki, Flavia Alman, Mario Canali, Interferenzen IV (on radio art) Liveness / Philip Auslander im digitalen Zeitalter / Uwe Jean Heuser Perform or else – from discipline to performance Videokunst in Deutschland 1963 – 1982 Arquitecturanimación / F. Massad, A.G. Yeste Ed. Bernd Schulz John Lasseter, Peter Conn, Eihachiro Nakamae, Edward Zajec, Franc Curk, Jasdan Joerges, Xavier Nicolas, TRANSIT #2 -

Heiner Goebbels: 'Ik Probeer De Hiërarchie Tussen De

HOLLAND FESTIVAL Dat doet u ook niet in uw eigen werk, wat is daarvoor de reden? HEINER GOEBBELS: ‘In het theater ligt een grote nadruk op het vertellen van verhalen, op het narratieve. We zijn daardoor als publiek ‘IK PROBEER DE HIËRARCHIE verplicht om het lineaire te volgen. Dat staat ons niet toe om alle registers te openen. Mijn werk is polyfoon, er zijn TUSSEN DE ELEMENTEN meerdere krachten in aanwezig, zoals licht, ruimte en geluid. Ik probeer de hi- erarchie tussen de elementen bewust te vermijden. Repertoire heeft dikwijls wel BEWUST TE VERMIJDEN’ een hiërarchie. Gertrude Stein zei ooit: “Alles wat geen verhaal is, zou een stuk Componist en theatermaker Heiner Goebbels is een vaste gast kunnen zijn.” Verhalen zijn volop aanwe- op het Holland Festival. Delusion of the fury is het zesde werk dat zig in ons dagelijkse leven, waarom zou ik daar nog een verhaal aan willen toe- het festival van hem toont. De veelzijdige kunstenaar is ook in- voegen? Er zitten wel degelijk verhalen tendant van de Ruhrtriennale (2012-2014), waar hij volgend jaar in mijn werk, vooral veel verschillende verhalen. De ruimte tussen die verhalen wordt opgevolgd door Johan Simons. Moos van den Broek sprak en tussen de elementen – tussen wat we met hem over het festival, zijn eigen werk en zijn rol als docent. zien en horen – is de drijvende kracht achter onze verbeelding. Die verbeelding heeft een kwaliteit die ik graag stimuleer. DOOR MOOS VAN DEN BROEK Een verhaal dwingt ons in een passieve positie. Ik geef de voorkeur aan ideeën orkesten, evenals vele muziektheater- waarbij het publiek zelf verbindingen stukken. -

Editorial Introduction Heiner Goebbels Entitles His Preface to This Collection

Editorial Introduction Heiner Goebbels entitles his preface to this collection ‘When a Tree is Already Being Mentioned, You Don’t Also Have to Show It’ wise counsel that should be borne in mind by anyone approaching artistic production or editorial introductions. As the general editor tasked with guiding the reader into this first English translation of his collected writings, I plead guilty to not always adhering to Goebbels’ advice, having been unable to resist including what is ‘already being mentioned’ in my overview. Perhaps it is Goebbels’ capacity to encapsulate, in a sentence or a phrase, a multitude of complex ideas germane to so many aspects of performance composition and reception that makes him so eminently quotable. Of course Goebbels is not simply talking about reiteration; he is talking about a familiar theatrical phenomenon whereby something being expressed in one medium is simultaneously duplicated in another, in this instance the aural and the visual. In the theatre this aesthetic doubling usually involves the presence of a performer as the primary expressive medium to which all other modes are inferior. As an alternative Goebbels posits a way of working that respects the value and integrity of all media and pays close attention to the individual qualities of materials. Writing about developments in performance in the mid eighties, Elinor Fuchs argued that the dominance of theatrical presence was being undermined by the work of the likes of Richard Foreman and Robert Wilson who by this time had established, ‘a theatre of Absence which by contrast disperses the center, displaces the Subject, destabilises meaning.’1 In his opening essay Goebbels cites Fuchs a number of times and explains how he has embraced dispersal and displacement as strategies in the creation of his own music - theatre works and as principles underpinning his teaching. -

Heiner Goebbels, Artist-In-Residence, Cornell University

Heiner Goebbels, Artist-in-Residence, Cornell University “Aesthetics of Absence: Questioning Basic Assumptions in Performing Arts” Cornell Lecture on Contemporary Aesthetics (9 March 2010) Copyright © Heiner Goebbels 2010 I could easily show you a fifty-minute video of one of my recent works, a performative installation without any performer (“Stifters Dinge”), then go away, and the topic of absence would be well covered. But maybe we should reflect instead on how this topic has developed over the years in my works in order to understand better what happens and what I mean by “absence.” How did it all start? Maybe with an accident in 1993 during rehearsals of a scene from a piece called “Ou bien le débarquement désastreux” (Or the hapless landing), one of my earliest music-theatre plays, with five musicians and one actor. Ou bien le débarquement désastreux Photo Credit: Dominik Mentzos Magdalena Jetelova, a highly renowned artist from Prague, created the stage: a gigantic aluminum pyramid that hangs upside down, has sand running out of it, and can be completely inverted during the show, and a giant wall of silk hair, driven smoothly by fifty fans behind it (which also drove the actor crazy). In one scene the actor disappears behind the wall of hair, in another he is sucked in completely by the hanging pyramid and then comes back, minutes later, head first. After the rehearsal of these scenes Magdalena Jetelova went directly to the actor, André Wilms, and enthusiastically told him: “It is absolutely fantastic when you disappear.” This is definitely something you should never say to an actor, and this one became so furious that I had to ask the set designer kindly not to visit any more rehearsals. -

WDR 3 Jazz, 11. März 2015

WDR 3 Jazz, 11. März 2015 Re:Active - Der Saxofonist Alfred 23 Harth zwischen Frankfurt und Seoul 22:00 – 23:00 Stand: 10.03.2015 E-Mail: [email protected] WDR JazzRadio: http://jazz.wdr.de/ Moderation: Harry Lachner Redaktion: Bernd Hoffmann Laufplan 1. Streetscenes: Seine Freunde K: Ulrike Haage, Alfred 23 Harth VLADIMIR ESTRAGON Tiptoe CD 888 803; LC: 07302 CD: Three Quarks for Muster Mark 1:45 2. Der Pflaumenbaum M: Heiner Goebbels, Alfred Harth, HEINER GOEBBELS, ALFRED HARTH T: Bertolt Brecht eva Records wwcx 2042; LC: 06383 CD: Goebbels Heart 1:40 3. Peking-Oper K: Heiner Goebbels, Alfred Harth HEINER GOEBBELS, ALFRED HARTH eva Records wwcx 2042; LC: 06383 CD: Goebbels Heart 4:45 4. Paradies und Hölle können eine Stadt sein K: Heiner Goebbels, Alfred Harth HEINER GOEBBELS, ALFRED HARTH eva Records wwcx 2042; LC: 06383 CD: Goebbels Heart 4:44 5. Just a Moment K: Just Music JUST MUSIC ECM 1002; LC: 02516 CD: The Cassiber Box 1982 - 1992 2:41 6. Peace K: Horace Silver TRIO VIRIDITAS Clean Feed Records CF 115 CD: Live at Vision Festival VI 3:54 7. Not Me K: Goebbels, Anders, Harth, Cutler CASSIBER ReR Megacorp ReR CBOX; LC: 02677 CD: The Cassiber Box 1982 - 1992 3:39 8. Le Detroit K: Lindsay Cooper, Alfred 23 Harth, TRABANT A ROMA Phil Minton ReR Megacorp ReR LC 2/3; LC: 02677 CD: Rarities Volumes 1 & 2 2:53 Dieses Manuskript ist ausschließlich zum persönlichen, privaten Gebrauch bestimmt. Jede weitere Vervielfältigung und Verbreitung bedarf der ausdrücklichen Genehmigung des WDR. 1 WDR 3 Jazz, 11. -

Driving Deeper Into That Thing

CriticalActs Driving Deeper into That Thing The Humanity of Heiner Goebbels’s Stifters Dinge Gelsey Bell Entering the expansive hall in the Park Avenue Adalbert Stifter, a 19th-century Romantic author Armory in New York City, all I could see were who is little known outside of Germany (though metal stairs leading up the back of a makeshift a number of his works have been translated into theatre, much like the ramp into an alien space- English).2 Originally premiered in September craft on a Hollywood set. Despite the distant 2007 at Théâtre Vidy in Lausanne, Switzerland, and ominous reverberations bouncing through Stifters Dinge has since been traveling through- the cavernous space, it was my footsteps, and out Europe, with runs in such cities as Berlin, those of the audience members in front of me, London, and Paris, as well as the Festival that lay the heavy tone upon the afternoon. The d’Avignon in France and BITEF (Belgrade pace was slow and felt preparatory rather than International Theatre Festival) in Serbia (where tired. Once at the top of the stairs, I was cloaked it won the Grand Prix “Mira Trailovic”) in 2008, in almost complete darkness — a stark contrast and Croatia’s World Theatre Festival in 2009. to the bright afternoon sun hitting the fresh It finally made its way to the New World for white snow on the city streets I had just walked five days in mid-December 2009, where I saw it in from. Turning a corner, I found myself at the on an uncharacteristically (for New York City) top of the small set of bleacher seats facing the snow-white Sunday afternoon. -

Heiner Goebbels Landschaft Mit Entfernten Verwandten Landscape with Distant Relatives Paysage Avec Parents Éloignés

ECM Heiner Goebbels Landschaft mit entfernten Verwandten Landscape with distant relatives Paysage avec parents éloignés Georg Nigl: baritone; David Bennent: voice Ensemble Modern Deutscher Kammerchor Franck Ollu: conductor ECM New Series 1811 CD 0289 476 5838 (2) Release: November, 13th 2007 Heiner Goebbels’ work confronts, contrasts and combines elements from multiple sources, often provocatively. The task of describing it, however, he leaves to others: “With all my work I try to make this question difficult,” he advised UK newspaper The Scotsman. “What drives the attention of an audience is the unforeseeable, and the secrets and the mystery of a performance.” This is surely the case with ‘Landschaft mit entfernten Verwandten’ (Landscape with Distant Relatives), officially ‘an opera’ yet one which stretches conventional definitions. Its many layers of meaning yield themselves up to repeated listening; ideas arrive in swarms. If music-theatre was its original context this ‘soundtrack’ version of it is packed with fascinating detail, drawing the listener in. “The acoustic aspect has a life of its own,” says Heiner Goebbels. The work was premiered at the Geneva Opera in October 2002 and was subsequently staged more than 20 times in Switzerland, France, Austria, the Netherlands, and Germany. The present recording is drawn from four performances at the Théâtre des Amandiers, Nanterre, Paris in October 2004. Goebbels has often talked about exploring the ‘landscape’ of a text and the writers identified as distant relatives here include, alphabetically, Giordano Bruno, Arthur Chapman, T.S.Eliot, Henri Michaux, Nicolas Poussin, Gertrude Stein, Leonardo da Vinci. Literary form and structure – the textual architecture – are frequently as important to the composer as content, and when setting, for example, Gertrude Stein, he is alert to the musicality of her phrases, which imply rhythms, pulses, melodic patterns. -

Programme (PDF)

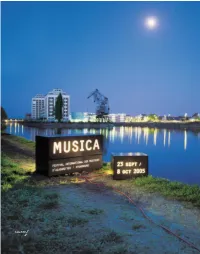

sommaire 6 Les partenaires institutionnels 7 Édito Rémy Pflimlin, président Jean-Dominique Marco, directeur 9 Éclipses dans le jardin Frank Madlener 10 L’affiche Directeur de publication Jean-Dominique Marco 12 Les compositeurs et les œuvres Rédaction Frank Madlener 15 Les trois impératifs de George Benjamin Éric Denut, musicologue Contributions Philippe Albèra, Eric Denut, Antoine Gindt, Marc Monnet, Max Noubel 19 Entretien avec Michael Jarrell Philippe Albèra, musicologue Secrétariat d’édition Camille Vier Coordination et suivi 23 Elliott Carter, portrait Mafalda Kong-Dumas Max Noubel, musicologue Conception graphique et photographies Poste 4 26 Programme détaillé Impression Ott Imprimeur 75 Les compositeurs © Musica 2005 – SACEM Licences de spectacle : 2-128734/3-125657 84 Les partenaires de Musica Crédits photographiques p. 14 et 27 Maurice Foxall / p. 17 Michiharu Okubo / p. 18, 19 et 71 Poste 4 / p. 22 et 51 Kathy Chapman / p. 24 Meredith Heuer / p. 27 Philippe Gontier / p. 28 Allison Jane Reed, DR, Carole Parodi, Mirjam Devriendt / p. 29 Mitch Jenkins / Warner Classics / p. 31 Marthe Lemelle, 92 Les actions pédagogiques Aymeric Warme-Janville / p. 32 DR / p. 33 Kass Kara photographers / p. 35 Pascal Bastien, Telemach Wiesinger (Bildkultur) / p. 36 Damien Guesnier, Instant Pluriel / p. 37 Lisa Rastl / p. 38 Olivier Roller / p. 40 Guillaume Jégou / p. 42 et 45 Guy Vivien / p. 43 Hanno Karttunen / 93 p. 46 Accroche Note, Guy Vivien / p. 47 DR / p. 48 Helge-Christoph L’équipe Borgelt, DR, Isabelle Vigier / Ben Van Duyi / p. 49 Tony Hutching / p. 51 Thomas Dashuber, Konzertgesellschaft / p. 53 DR / p. 54 Jean-Claude Dorn / p.