Farming to Halves A) Farming to Halves at Hunstanton, from the Notebook of Sir Nicholas Le Strange

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contents of Volume 14 Norwich Marriages 1813-37 (Are Distinguished by Letter Code, Given Below) Those from 1801-13 Have Also Been Transcribed and Have No Code

Norfolk Family History Society Norfolk Marriages 1801-1837 The contents of Volume 14 Norwich Marriages 1813-37 (are distinguished by letter code, given below) those from 1801-13 have also been transcribed and have no code. ASt All Saints Hel St. Helen’s MyM St. Mary in the S&J St. Simon & St. And St. Andrew’s Jam St. James’ Marsh Jude Aug St. Augustine’s Jma St. John McC St. Michael Coslany Ste St. Stephen’s Ben St. Benedict’s Maddermarket McP St. Michael at Plea Swi St. Swithen’s JSe St. John Sepulchre McT St. Michael at Thorn Cle St. Clement’s Erh Earlham St. Mary’s Edm St. Edmund’s JTi St. John Timberhill Pau St. Paul’s Etn Eaton St. Andrew’s Eth St. Etheldreda’s Jul St. Julian’s PHu St. Peter Hungate GCo St. George Colegate Law St. Lawrence’s PMa St. Peter Mancroft Hei Heigham St. GTo St. George Mgt St. Margaret’s PpM St. Peter per Bartholomew Tombland MtO St. Martin at Oak Mountergate Lak Lakenham St. John Gil St. Giles’ MtP St. Martin at Palace PSo St. Peter Southgate the Baptist and All Grg St. Gregory’s MyC St. Mary Coslany Sav St. Saviour’s Saints The 25 Suffolk parishes Ashby Burgh Castle (Nfk 1974) Gisleham Kessingland Mutford Barnby Carlton Colville Gorleston (Nfk 1889) Kirkley Oulton Belton (Nfk 1974) Corton Gunton Knettishall Pakefield Blundeston Cove, North Herringfleet Lound Rushmere Bradwell (Nfk 1974) Fritton (Nfk 1974) Hopton (Nfk 1974) Lowestoft Somerleyton The Norfolk parishes 1 Acle 36 Barton Bendish St Andrew 71 Bodham 106 Burlingham St Edmond 141 Colney 2 Alburgh 37 Barton Bendish St Mary 72 Bodney 107 Burlingham -

Hempton to South Creake Cable Route Hempton, Dunton, Sculthorpe and South Creake Norfolk

Hempton to South Creake Cable Route Hempton, Dunton, Sculthorpe and South Creake Norfolk Programme of Archaeological Recording for Lark Energy CA Project: 660529 CA Report: 15762 SMS and Earthwork Survey Event No: ENF138499 Watching Brief Event No: ENF138543 October 2015 Hempton to South Creake Cable Route Hempton, Dunton, Sculthorpe and South Creake Norfolk Programme of Archaeological Recording CA Project: 660529 CA Report: 15762 Document Control Grid Revision Date Author Checked by Status Reasons for Approved revision by A 15/10/2015 SRJ SCC Internal SCC review This report is confidential to the client. Cotswold Archaeology accepts no responsibility or liability to any third party to whom this report, or any part of it, is made known. Any such party relies upon this report entirely at their own risk. No part of this report may be reproduced by any means without permission. © Cotswold Archaeology © Cotswold Archaeology Hempton to South Creake cable route: Programme of Archaeological Recording CONTENTS SUMMARY ..................................................................................................................... 2 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................ 3 2. ARCHAEOLOGICAL BACKGROUND ................................................................ 4 3. AIMS AND OBJECTIVES ................................................................................... 5 4. METHODOLOGY .............................................................................................. -

Parish Registers and Transcripts in the Norfolk Record Office

Parish Registers and Transcripts in the Norfolk Record Office This list summarises the Norfolk Record Office’s (NRO’s) holdings of parish (Church of England) registers and of transcripts and other copies of them. Parish Registers The NRO holds registers of baptisms, marriages, burials and banns of marriage for most parishes in the Diocese of Norwich (including Suffolk parishes in and near Lowestoft in the deanery of Lothingland) and part of the Diocese of Ely in south-west Norfolk (parishes in the deanery of Fincham and Feltwell). Some Norfolk parish records remain in the churches, especially more recent registers, which may be still in use. In the extreme west of the county, records for parishes in the deanery of Wisbech Lynn Marshland are deposited in the Wisbech and Fenland Museum, whilst Welney parish records are at the Cambridgeshire Record Office. The covering dates of registers in the following list do not conceal any gaps of more than ten years; for the populous urban parishes (such as Great Yarmouth) smaller gaps are indicated. Whenever microfiche or microfilm copies are available they must be used in place of the original registers, some of which are unfit for production. A few parish registers have been digitally photographed and the images are available on computers in the NRO's searchroom. The digital images were produced as a result of partnership projects with other groups and organizations, so we are not able to supply copies of whole registers (either as hard copies or on CD or in any other digital format), although in most cases we have permission to provide printout copies of individual entries. -

Agenda, So As to Save Any Unnecessary Waiting by Members of the Public Attending for Such Applications

Development Committee Please contact: Linda Yarham Please email: [email protected] Direct Dial: 01263 516019 14 February 2018 A meeting of the Development Committee will be held in the Council Chamber at the Council Offices, Holt Road, Cromer on Thursday 22 February 2018 at 9.30am. Coffee will be available for Members at 9.00am and 11.00am when there will be a short break in the meeting. A break of at least 30 minutes will be taken at 1.00pm if the meeting is still in session. Any site inspections will take place on Thursday 15 March 2018. PUBLIC SPEAKING – TELEPHONE REGISTRATION REQUIRED Members of the public who wish to speak on applications are required to register by 9 am on Tuesday 20 February 2018 by telephoning Customer Services on 01263 516150. Please read the information on the procedure for public speaking on our website here or request a copy of “Have Your Say” from Customer Services. Anyone attending this meeting may take photographs, film or audio-record the proceedings and report on the meeting. Anyone wishing to do so must inform the Chairman. If you are a member of the public and you wish to speak, please be aware that you may be filmed or photographed. Emma Denny Democratic Services Manager To: Mrs S Arnold, Mrs A Fitch-Tillett, Mrs A Green, Mrs P Grove-Jones, Mr B Hannah, Mr N Lloyd, Mr N Pearce, Ms M Prior, Mr R Reynolds, Mr P Rice, Mr S Shaw, Mr R Shepherd, Mr B Smith, Mrs V Uprichard Substitutes: Mr D Baker, Mrs S Bütikofer, Mr N Coppack, Mrs A Claussen-Reynolds, Mrs J English, Mr T FitzPatrick, Mr V FitzPatrick, Mr S Hester, Mr M Knowles, Mrs B McGoun, Mrs J Oliver, Miss B Palmer, Mrs G Perry-Warnes, Mr J Punchard, Mr J Rest, Mr E Seward, Mr D Smith, Mr N Smith, Ms K Ward, Mr A Yiasimi All other Members of the Council for information. -

Harvest Edge, Wyre Common Offers Over Neen Savage, Nr Cleobury Mortimer, DY14 8HG £399,999 Harvest Edge, Wyre Common

Harvest Edge, Wyre Common Offers over Neen Savage, Nr Cleobury Mortimer, DY14 8HG £399,999 Harvest Edge, Wyre Common Neen Savage, Nr Cleobury Situated on the edge of Cleobury Mortimer this four bedroom bungalow offers versatile accommodation for any family with outstanding and far reaching views across the valley, including the famous crooked spire of St Marys Church. From the opposite direction when driving through the town of Cleobury Mortimer the property can be clearly seen on the horizon. • Four bedroom bungalow • Outstanding far reaching views • Located in the Parish Neen Savage • Excellent schooling • Parking for five Plus cars • Secluded spot Directions From Ludlow head over Clee Hill and continue on that road until you come to the small town of Cleobury Mortimer, continue through the village and take the left hand turn towards Bridgnorth and Neen Savage and head towards golf course, the property is located on the right hand-side diagonally opposite the entrance to the Golf course. Introduction Do you have a property to sell or rent? The property benefits from a master bedroom with the scope for a potential En We offer a free market appraisal and Suite currently being used as a dressing room, a double guest bedroom with En according to Rightmove we are the number Suite, two further bedrooms, a hobbies room, drying room and a family bathroom. one agent across our region for sales and The living space consists of a kitchen which flows into the dining room with dual lets agreed* aspect windows with views out, a spacious lounge, with double doors out to a decking BBQ area with garden surrounding and study. -

Winter/Spring 2005 ● Issue No.9

Winter/Spring 2005 ● Issue No.9 HOLKHAM NEWSLETTER HERE might be a perception that all the changes we have seen at Holkham have taken place only in the last five or six years.This process might have been more rapid in that time, but that only Treflects the speed of change in the world in general. Change has always been with us. Mick Thompson, recently retired from the Hall, recalls how he helped to modernise four milking parlours on the Estate.Well, how many have we now? None: this is change brought on by economic circumstances. I started farming at Burnham Norton, 36 years ago, with 11 men. By the time the Holkham Farming Company took over, that was down to only three, again a reflection of changed economic circumstances, and a necessary adaptation to new farming practices. Now, seven men look after 5,000 acres. A good example of adaptation is the transformation of the 18th century Triumphal Arch into a chic annexe of The Victoria Hotel, thus turning a long-standing liability to economic advantage, and moreover, making use of a perfectly sound building. I never see the point of new build if existing buildings can be satisfactorily adapted without compromising their character. But with change, it is important to retain and value the best of the past. Nicholas Hills writes about the restoration of the family monuments at Tittleshall Church, to which the Estate contributed a large part of the £70,000 costs.We could have saved our money, but then part of the history of this great Estate would have been lost. -

An Archaeological Analysis of Anglo-Saxon Shropshire A.D. 600 – 1066: with a Catalogue of Artefacts

An Archaeological Analysis of Anglo-Saxon Shropshire A.D. 600 – 1066: With a catalogue of artefacts By Esme Nadine Hookway A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of MRes Classics, Ancient History and Archaeology College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham March 2015 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract The Anglo-Saxon period spanned over 600 years, beginning in the fifth century with migrations into the Roman province of Britannia by peoples’ from the Continent, witnessing the arrival of Scandinavian raiders and settlers from the ninth century and ending with the Norman Conquest of a unified England in 1066. This was a period of immense cultural, political, economic and religious change. The archaeological evidence for this period is however sparse in comparison with the preceding Roman period and the following medieval period. This is particularly apparent in regions of western England, and our understanding of Shropshire, a county with a notable lack of Anglo-Saxon archaeological or historical evidence, remains obscure. This research aims to enhance our understanding of the Anglo-Saxon period in Shropshire by combining multiple sources of evidence, including the growing body of artefacts recorded by the Portable Antiquity Scheme, to produce an over-view of Shropshire during the Anglo-Saxon period. -

![NORFOLK.] FARMERS-Continued](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0304/norfolk-farmers-continued-1730304.webp)

NORFOLK.] FARMERS-Continued

' TRADES DIRECTORY.] 603 FAR [NORFOLK.] FARMERS-continued. Carter James, Antingham, Norwich Chapman John, Ormesby St. Michael, Butter John, Tottenhill, Lynn Carter J oscph, Mansion green, Harding- Yarmouth Butter Thomas, Marham, Downham ham, Attleborough Chapman Jo!!eph, Starston, Harleston llutterick J ames, Wiggenhall St. Mary Carter Robert, Dough ton, Brandon Chap man Robt. Ut.Cressinghm. Thetfrd Magdalen, Lynn Carter Robert, Gissing, Diss Chapman Thomas, Fundenhall, Wy- lluttifimt "\Villiam Henry, Bawburgl1, Carter Samuel, Darrow farm, Diss mondbam Norwich Carter Thomas, Roydon, Lynn Chapman Thomas, Heywood, Diss lluttolph William,Silfleld,Wymondham Carter "\Villiam, Foulden, Brandon Chapman William,EastBilney,Swaffhm ButtolphWilliam Kiddle,Saham\Veight, Carter "\Villiam, Gissing, Diss Chapman "\Villiam, Grimston, Lynn Saham Toney, Thetford Carter \Villiam, Gooderstone, Brandon Chapman William, Ilockham, 'fhetford Button John, Topcroft, Bun gay Carter \Villiam, Wretton, Brandon Chap man William, Loddon, Norwich Button "\V m. Rorlwell,Denton,Harleston Carter \Villiam Eaton, Burston, Diss Chapman \V m. Runham, Filby,Norwich Buxbn Frederick, Easton, Norwich Carver William, Hardley, Norwich Chapman Wllliam Stamp, Potter lluxton Robert, North Wootton, Lynn Cary John, Reymerstone, Attleborough Heigham, Norwich Byles Robert, Newton Flotman, Long Case Charles, Toftrees hall; Fakenhnm Chase Charles, Market place, Diss 8tratton Case Edward, Cockthorpe, Wells Chase Charles, Walcot hall, Diss By worth Thomas, Strausett, Downham Case J ames Lee, Hey don road, Aylsham, Chase John, AI burgh, Harleston Cable .Mrs. Han·iet, Rockland St. Pe- Norwich ChaterWillis,Forrlham,Downham 1\Irkt ter, Attleborough Case J amcs Philip, Testerton, Fakenham ChattonJ ames,CarletonRode, Att leboro' Cackett J esse,Fincham,Downhm.Mrket. Case Robert, Ililgay, Down ham Market Cheetham Charles, Boughton, Brandon Caddy Mrs.Hannah,Carbrooke, Thetford I Case Thos. -

English Hundred-Names

l LUNDS UNIVERSITETS ARSSKRIFT. N. F. Avd. 1. Bd 30. Nr 1. ,~ ,j .11 . i ~ .l i THE jl; ENGLISH HUNDRED-NAMES BY oL 0 f S. AND ER SON , LUND PHINTED BY HAKAN DHLSSON I 934 The English Hundred-Names xvn It does not fall within the scope of the present study to enter on the details of the theories advanced; there are points that are still controversial, and some aspects of the question may repay further study. It is hoped that the etymological investigation of the hundred-names undertaken in the following pages will, Introduction. when completed, furnish a starting-point for the discussion of some of the problems connected with the origin of the hundred. 1. Scope and Aim. Terminology Discussed. The following chapters will be devoted to the discussion of some The local divisions known as hundreds though now practi aspects of the system as actually in existence, which have some cally obsolete played an important part in judicial administration bearing on the questions discussed in the etymological part, and in the Middle Ages. The hundredal system as a wbole is first to some general remarks on hundred-names and the like as shown in detail in Domesday - with the exception of some embodied in the material now collected. counties and smaller areas -- but is known to have existed about THE HUNDRED. a hundred and fifty years earlier. The hundred is mentioned in the laws of Edmund (940-6),' but no earlier evidence for its The hundred, it is generally admitted, is in theory at least a existence has been found. -

The Times , 1992, UK, English

ES MONDAY FEBRUARY 3 1992 JAMES GRAY Minister backs wider choice Abductor linked TODAY IN THE TIMES to food GETTING AWAY poison threats m&K- m** - By Craig Seton &*+ ~ .. * *#:- * POLICE are investigating whether the kidnapper of mi=T.r^ Europe, Asia, grammar school Stephanie Slater could be a America., faffed “consumer terrorist” MM •> wherever the who tried to exton money by in By threatening world want to 4tew John O leary, higher education correspondent to contaminate you supermarket food. * a«~ -*r go, a friend can THE Conservative party schools could reappear would lead to the re-emer- Tom Cook, head of a joint 9k -r- fly free and stay sprung a pre-election sur- throughout the counby, as gence of grammar schools: police investigation into the fa> t*C*. free with the six prise yesterday by signal- long as there were not too Jack Straw. Labour's educa- abduction of Miss Slater and Times privilege ling the return of gram- mapy in each area. tion spokesman, said: “The the murder last year of Julie He has always opposed a Conservatives are paralysed Dan, said yesterday tokens being mar schools as part of a that pos- return to the mix ofgrammar on this issue because they sible links were being exam- more diverse state educa- published earn * and secondary, modern know that the remtraduction ' ined with seven or eight faffed tion system. I’ day this week. ..'.SV* ' schools created by the 1944 of selection at 11 is not want- d> attempts at extortion involv- In a significant shift of l Collect the second Education Act, arid he reiter- ed by the majority of parents. -

![NORFOLK.] FARM Ers-Rontinued](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1968/norfolk-farm-ers-rontinued-1851968.webp)

NORFOLK.] FARM Ers-Rontinued

TRADES DIRECTORY.] 6~3 FAR [NORFOLK.] FARM ERs-rontinued. ·wood William, Morston, Thetford Wright Stephen, V't'alcot green, Diss Wilkins William, Acle, Norwich Woodcock Geo. Barford, Wymondham Wright Thomas, Ludham, Norwich \Vilkinson Jeremiah, Wiggenhall St. Woodcock Horace Robt. Fet·sflP.!d, Diss \Vright Thoma;;:, North Runcton, Lynn Ge1·mtJ.in, Lynn \V oodcock John, Billiu~ford, Thetford \VrightThos.'l'.'l'erringtonSt.J ohn,Lynn Wilki1tson .folm, Green, Wicklewood, Woodcock Joseph, Horsham ::lt. Faith's, \V right \Villiam, Briston, Thetf'ord Wymondham Norwich Wright \Villiam, Felthorpc, Norwich Wilkinson Thomas, Mattishall Burgh, Woodcock Robert, Bressinf!ham, Diss Wri~ht Wm. F1elrl Dalling, Thetfonl ERst Dereham Woodcock Williarn, Salhnuse, Norwich Wri~ht Wm. North Creake, Faktmham WillP.rWm. Spa common, North \Valsbm W oodhouse Charles, l~oxley, Thetford Wrigh t \Villiam, Ovington, Thetford 'Vil\Q.'ress John Daniel, Upton, Norwich Woodhouse Williarn, Briston, Thetford Wright William,Pulham St. Mary-the- Williams John, Eastgate, Cawston: Woodrow John, Blofield, Norwich Virgin, Harleston Norwich Woodrow William, Walcot green, Diss Wright \Villiam, Smallbur!!h, Norwich Williams John, Soulhgate, Cawston, Woodrow William, \Vorstead, Norwich Wright William, Toftrees, Fa ken ham Norwich • WoodsChristopher, Sidestrand,Norwich \'VrightVVm. WalpoleSt. Peter,Wishech \Yilliams Jonathan, Fersfield, Diss Woods Henry, Church end, Walpole St. Wrightup Hen. Farrer, Ashill, Thetford Williamson Chafl. Alpington, Norwich Peter, Wisbech Wyatt Daviu, Yaxham, East Dereham \Vi\liamson Fredk. Horsford, Norwich Woods Henry, \Vortwell, Harleston Wyatt .John, Hingham, Attleboruugh vVilliamson John, Briston, Tbetford Woods John, Hedenham, Bungay Wyatt Robert, \Vestfield, EastDereham Williamson John, Coldham farm, Woods Nicholas, Gayton, Lynn W yer John Georg·e, Sou thery,Downham Shernbourne, Lynn Woods Thomas, Sharring-ton, Thetford Wyett Thomas, Shipdharn, Thetford 'Villiamson Thomas John Elliott, Old Woodward Henry, 'ferrington St. -

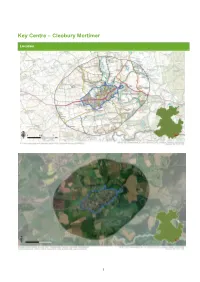

Cleobury Mortimer

Key Centre – Cleobury Mortimer Location 1 Summary of Settlement Study Area and Location Introduction Cleobury Mortimer, in south east Shropshire has been identified as a Key Centre within the Shropshire Pre-Submission Draft Local Plan (2020). This Green Infrastructure Strategy has defined the study area as a 1km buffer around this settlement. Cleobury Mortimer, is a rural market town located on the western side of the River Rea, just over 4km east of the Clee Hills and 3km west of the Wyre Forest. It is around 17km to the east of Ludlow and a similar distance to the west of Kidderminster. The town has a population of just over 3,000. And around 1,306 dwellings. Development context Existing development allocations in the town are set out in the SAMDev (2015)1, however the Shropshire Local Plan is currently being reviewed. The Pre-Submission Draft Local Plan (2020) proposes other sites, which are not yet adopted. The Shropshire Pre-Submission Draft Local Plan (2020) outlines that Cleobury Mortimer Town Council are developing a Neighbourhood Plan and so it is intended that Shropshire Council will work closely with the Neighbourhood Plan Steering Group to provide an overall housing guideline for the town, with the Neighbourhood Plan determining how growth should be managed and potentially identifying a development boundary for the town and any specific allocations. The Plan Review identifies that the town has a remaining residential requirement of approximately 120 dwellings and 1ha of employment land to be delivered over the Plan period up to 2038. The locations of potential allocations to deliver these requirements are to be determined by the Neighbourhood Plan.