Triple-Threat Studio Skills

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Interview with LINCOLN MAYORGA Was Conducted by the Library of Congress on July 14, 2015

This interview with LINCOLN MAYORGA was conducted by the Library of Congress on July 14, 2015. Lincoln Mayorga LOC: In an online narrative you wrote about the creation of Sheffield Lab, you mention that “one afternoon in 1959” you and Doug Sax went to Electrovox studios. Had you done research and scoped out that facility prior to your visit? LM: I had been there before in 1955 with a singer for some demos so I was aware of the place. It looked like an old-time radio studio—which is what it was. Equipment from the 1930s and 40s. It had had the same ownership since 1931. We [LM and Doug Sax] had been speculating about what went on with tape recording. It occurred to us that if one went direct to disc we could bypass the negative qualities of tape. And that dawned on me one day when we were in the neighborhood. The studio had not changed in decades. We went in, they were not busy, they were delighted to to talk to us. We asked them if they would let us cut a demo disc but NOT the way they normally would, but record directly to their cutting system. Their equipment was amazingly well preserved, though antique. The microphones were RCA ribbon microphones, one-time broadcast standard. Their lathe was from the age of early talking pictures, around 1929. So, without much ado, we cut a disc. When we were done, I didn’t want to play it on their equipment. I thought their tone arm was too heavy and I didn’t want to do damage to the disc. -

PINK FLOYD: the Division Bell

im Auftrag: medienAgentur Stefan Michel T 040-5149 1467 F 040-5149 1465 [email protected] PINK FLOYD: The Division Bell 20TH ANNIVERSARY BOX SET Erstmals im 5.1 Surround Sound Mix Blu-Ray-Disc mit neuem Clip zu Marooned von 2014 Doppel-Vinyl mit erstmalig ungekürzten Songs 7- und 12-Zoll Vinyl-Repliken VÖ: 27. Juni 2014 Zum 20. Jahrestag des 1994er Albums The Division Bell präsentieren PINK FLOYD das Album in einer umfangreich ausgestatteten Box, die aus insgesamt vier Vinyl-Schallplatten, einer CD, einer Blu-Ray-Disc und fünf Kunstdrucken für Sammler besteht. Neben dem vollständigen Original-Album als Doppelvinyl im Klappcover von Hipgnosis/Storm enthält das 20th Anniversary Box-Set „The Division Bell“ das Discovery Remaster des Albums aus dem Jahr 2011, die Single Take It Back in einer Replik des roten 7-Zoll-Vinyls, eine Replik der 7-Zoll Single High Hopes in klarem Vinyl und eine 12-Zoll Replik des Songs in blauem Vinyl mit lasergeätztem Design. Eine Blu-Ray-Disc enthält überdies das gesamte Album in HD Audio und einem bisher unveröffentlichten Audio- Mix des Albums im 5.1 Dolby Surround Sound von Andy Jackson. Ebenfalls auf der Blu-Ray-Disc: Ein neu gedrehtes Video zum Song Marooned, der 1994 mit einem Grammy als „Best Rock Instrumental“ ausgezeichnet wurde. Der Clip wurde von Aubray Powell für Hipgnosis in der ersten Aprilwoche 2014 in der Ukraine gedreht! Die Audios zum Clip sind sowohl in PCM Stereo als auch in Jacksons 5.1.-Mix abrufbar. Das Vinyl-Album wurde auf Grundlage der analogen Mastertapes von Doug Sax im Masterin Lab remixt. -

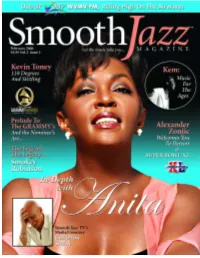

Smooth Jazz Magazine February 06.Pdf

2 SmoothJazz Magazine Let the music take you . 31 28 14 F E AT U R E S 38 TRAVEL DESTINATION 14 ALEXANDER ZONJIC DETROIT the HOME of SUPERBOWL XL 28 SMOKEY ROBINSON LEGACY–Still Croonin’ 31 KEM Music For The Ages 42 38 ANITA BAKER In Depth With Anita 42 KEVIN TONEY Is Right on Time 59 18 23 52 D E PA R T M E N T S 7 JAZZ NOTES & BIRTHDAYS 12 ON STAGE LIFESYTYLE 18 - CAMERON SMITH 50 - GRAMMY PRELUDE and the nominees are... 50 23 STAR LOUNGE - STACY KEACH 27 CONCERT REVIEW - EARL KLUGH 52 RISING STAR - MIKE PHILLIPS 59 REMEMBERING... - SHIRLEY HORN 60 CD REVIEWS 62 RADIO LISTINGS 64 JAZZLE PUZZLE 65 CD RELEASES 66 CONCERT LISTINGS 70 TRAVEL PLANNER ™ Let the music take you . M A G A Z I N E VOLUME 2 ISSUE 1 January / February 2006 PUBLISHER/CEO Art Jackson RESEARCH DIRECTOR Doris Gee MARKETING DIRECTOR Mark Lawrence Burwell ART DIRECTOR Danielle Cheek COPY EDITORS Karly Pierre, Teresa Fowler CONTRIBUTING WRITERS Ahli Love PHILADELPHIA Amy Rogin LOS ANGELES Belinda Harris DETROIT Cheryl Boone VIRGINA BEACH Karly Pierre LOS ANGELES Jonathan Barrick LOS ANGELES M.L. Burwell LOS ANGELES S TAFF PH OTOG RA PH E R Ambrose CONTRIBUTING PHOTOGRAPHERS Amy Rogin, Diane Hadley, Joseph D. Williams, Mann ADVERTISING SALES David Facinelli Facinelli Media Sales 1400 E. Touhy Ave., Suite 260 Des Plaines, IL 60018 727-866-9647 Tel 727-866-9222 Fax [email protected] SmoothJazz Magazine Inc. office: 3748 Keystone Avenue, Suite #406 Los Angeles, CA 90034 tel: 310.558.4698 Fax: 952.487.4999 email: [email protected] www.smoothjazzmag.net Talk To SmoothJazz Magazine Inc. -

Pink Floyd Feirer Jubileum Med Nytt Vinylslipp

Pink Floyd - Division Bell 11-04-2019 15:00 CEST Pink Floyd feirer jubileum med nytt vinylslipp Pink Floyd Records feirer 25-års jubileet til The Division Bell, albumet fra 1994 som har solgt for mange millioner og inneholder den Grammy-vinnende låta "Marooned", med å gi ut en ny versjon. Den vil bli utgitt 7. juni som gjennomsiktig blå vinyl (lik den originale utgivelsen) fra 1994. The Division Bell var det siste studioalbumet som ble spilt inn med bandet: David Gilmour, Nick Mason og Richard Wright. Albumet gikk rett inn på 1. plass Storbritannia, USA, Australia og New Zealand, lå som nr. 1 i fire uker på den amerikanske Billboard-listen og har i dag solgt over 12 millioner eksemplarer. The Division Bell ble spilt inn i Astoria og Britannia Row Studios og majoriteten av tekstene ble skrevet av Polly Samson og David Gilmour. David Gilmour uttalte følgende: “The three of us went into Britannia Row studios, and improvised for two weeks. Playing together and starting from scratch was interesting and exciting, it kick-started the album and the process was very good, it was collaborative and felt more cohesive.” The Division Bell inneholder 11 låter inkludert "A Great Day For Freedom", "Keep Talking" (featuring a sampled Stephen Hawking), "High Hopes", og Pink Floyd’s eneste Grammy-vinnende låt, instrumental-låta "Marooned". En video for "Marooned"ble laget for 20-årsjubileet da man slapp Immersion- utgivelsen av albumet, og har nå blitt sett av over 25 millioner. Denne høyt anerkjente videoen ble produsert Aubrey Powell fra Hipgnosis, filmet i Chernobyl og inneholdt også utrolige bilder fra verdensrommet filmet av NASA. -

Surround Producen, Opnemen, Mixen En Masteren

De bij de Grammy-organisatie aangesloten producers en geluidstechnici hebben diverse gedachten over surroundproductie samengebracht in een pdf-document dat je gratis kunt downloaden van event Grammy-genomineerde producers bespreken de stand van zaken www.grammy.com/pe_wing/guidelines/index.aspx Surround producen, opnemen, mixen en masteren kunnen spreken en zijn ze bovendien vrijwel Bob Clearmountain gaf ook aan dat hij dekken en daarmee een nieuwe richting zullen allemaal alleen voor stereoweergave geschikt. extremere stereo panning gebruikt bij surround vaststellen voor surround sound producties mixen, omdat er meer plaats is dankzij de en mixages. center speaker. Het feit dat de center speaker De producers zijn het er over eens dat de Van formaat bijvoorbeeld voor de lead vocal gebruikt kan manier waarop een productie tot stand komt De discussie over de formaten was zeer ver- worden laat meer ruimte over op ‘left’ en ‘right’. in hoge mate bepalend is voor wat er na makelijk. Zelfs onderling was er verschil van Elliot Scheiner: “De dvd van de Eagles was afloop mogelijk is. Werken met opnames die mening over de opties en mogelijkheden m’n eerste surround mix. Ik had het idee dat niet oorspronkelijk voor surround bedoeld van HD-DVD, SACD en DVD-A. Doug Sax: de center speaker de definitie kon verbeteren zijn, beperkt de mogelijkheden enorm. “Als het de bedoeling van de industrie is en ik plaatste er veel vocals. Maar dat werkte geweest om verwarring te zaaien, dan is er nogal afleidend. Ook als de center speaker fantastisch werk verricht...” uit is, moet je nog een goede vocal mix over- Avalon Het panel benadrukte verder dat de huidige houden. -

Press Release

PRESS RELEASE • FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE • 31/03/14 CONTACT For review enquiries please e-mail: [email protected] For ATC info contact: [email protected] ATC SCM150ASL PRO makes mastering clear as day at Jacob’s Well “The biggest strength of the ATCs are their ability to present the midrange at its best, which helps me a lot in terms of evaluating the mix and deciding what to do with it.” - Sangwook ‘Sunny’ Nam (Owner, Jacob’s Well Mastering) WEST LEBANON, NH, USA: specialist British loudspeaker drive unit and complete sound reproduction system manufacturer ATC is proud to announce that Grammy®-nominated mastering engineer Sangwook ‘Sunny’ Nam has installed a pair of custom SCM150ASL PRO three-way active loudspeakers at his unique Jacob’s Well Mastering facility founded in 2012… “The reason I decided to go with ATC is that I had used ATC speakers during my time at The Mastering Lab.” So states Sangwook ‘Sunny’ Nam, a protégé of mastering legend Doug Sax at The Mastering Lab in Hollywood (and, later, Ojai, California) from July 2005 until flying solo, setting up shop towards the Eastern Seaboard at a scenic riverside location in West Lebanon, New Hampshire. How, why, and when Korean native Nam needed to seek out a mastering mentor before becoming an internationally sought-after mastering engineer in his own right makes for fascinating reading. “I began my career as a recording engineer in 1998,” Nam begins. “Establishing myself as a top producer for classical music recordings and as an engineer for audiophile recordings in Korea, I worked with well-known musicians, such as Myungwha Chung, Daejin Kim, and Yeol Eum Son, and also a range of orchestras, including the Hong Kong Philharmonic, Polish National Radio Symphony, and Nashville Symphony. -

ATC SCM 50ASLT Classic Tower.Pdf

1 Review by James L. Darby ATC SCM 50ASLT Classic Tower ( Active ) in Black Ash - $20,900 With Cherry Finish as tested - $21,600.00 If you are not familiar with the ATC brand of speakers, you are probably not involved in the recording industry. ATC speakers and electronics are as common in recording, mixing and mastering studios as rainy days in Seattle. According to their website, artist 2 who use ATC speakers include Pink Floyd, Mark Knopfler, Tom Petty, the Rolling Stones to name just a few. The people who make those artists sound good are the engineers and the list there is even more impressive with names like Doug Sax, George Massenburg and Bob Ludwig among them. Sony uses ATC’s in their New York SACD studios. So does Abbey Road, Warner Brothers, Polygram and Naxos among many others. One name listed jumped out at me as a guy I had exchanged several emails with over the years. He recently won his seventh Grammy for engineering on the Telarc label. His name is Michael Bishop. So, I dropped him a line and asked if he and Telarc did indeed use ATC monitors. His answer was an enthusiastic “Yes! I use the ATC SCM- 50s quite frequently at Telarc, in studios and at home. I’m a big fan of ATC’s speakers in general. My associate, Rob Friedrich, also uses the ATC’s almost exclusively in his sessions. We have ATC’s in every post-production room and on every Telarc session”. In addition, from ATC's website is this quote: Whether at home in Cleveland or on the road, he relies on five ATC 150 midfield monitors. -

Pink Floyd a Saucerful of Secrets = 神秘 Mp3, Flac, Wma

Pink Floyd A Saucerful Of Secrets = 神秘 mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: A Saucerful Of Secrets = 神秘 Country: Japan Released: 2001 Style: Psychedelic Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1134 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1824 mb WMA version RAR size: 1704 mb Rating: 4.3 Votes: 488 Other Formats: VQF AC3 MMF MOD XM FLAC AU Tracklist Hide Credits Let There Be More Light = 光を求めて 1 5:33 Written-By – Roger Waters Remember A Day = 追想 2 4:29 Written-By – Rick Wright* Set The Controls For The Heart Of The Sun = 太陽讃歌 3 5:23 Written-By – Roger Waters Corporal Clegg = コーポラル・クレッグ 4 4:07 Written-By – Roger Waters A Saucerful Of Secrets = 神秘 5 Written By – Waters-Wright-Mason-GilmoreWritten-By – Gilmore*, Mason*, Wright*, 11:52 Waters* See-Saw = シーソー 6 4:32 Written-By – Rick Wright* Jugband Blues = ジャグバンド・ブルース 7 2:59 Written-By – Syd Barrett Companies, etc. Record Company – Toshiba EMI Ltd – TOCP-65732 Manufactured By – Toshiba EMI Ltd Phonographic Copyright (p) – EMI Records Ltd. Copyright (c) – EMI Records Ltd. Mastered At – The Mastering Lab Credits Design [Sleeve], Photography By [Photos By] – Hipgnosis Liner Notes [対訳] – 山本安見* Producer [Produced By] – Norman Smith Remastered By [Digitally] – Doug Sax Supervised By [Remastering] – James Guthrie Notes This CD is part of the "mini LP" series where everything has been faithfully reproduced to mimmick the original LP release, but in a CD format. 'A Saucerful Of Secrets' was among the first to be released this way so it's not quite an exact reproduction and is far less complete than later reissues (i.e. -

Steve Turre Artist Q&A

JazzWeek with airplay data powered by jazzweek.com • December 10, 2004 Volume 1, Number 5 • $7.95 In This Issue: Lundvall Feted TURRE’S TRIBUTE TO by MIDEM . 7 Botti Tours with RAHSAAN Groban . 7 Interview: Steve Turre’s Cole Estate The Spirits Up Above Saves the p10 Music . 8 Brown Inaugurated At Berklee . 9 Reviews and Picks. 14 Soweto Kinch Live . 14 Jazz Radio . 17 47th GRAMMY Smooth Jazz Radio. 22 NOMINATIONS Radio Jazz,Contemporary Jazz, Panels. 26 Latin Jazz,Arranging, Q&A with Sunnyside’s More News . 4 Vocals and more ... p4 Garrett Shelton p12 Charts: #1 Jazz Album – Dr. Lonnie Smith #1 Smooth Album – Richard Elliot #1 Smooth Single – Richard Elliot JazzWeek This Week EDITOR Ed Trefzger It’s almost the end of the year, and we’re getting ready to look back on CONTRIBUTING EDITORS 2004. We’d like all our subscribers to put together a Top 10 list from this Keith Zimmerman year. Details about it are on page 15. Tad Hendrickson will be compil- Kent Zimmerman ing the infomation for our year-end double issue, which comes out Dec. 31. Tad Hendrickson (There will be no issue on Dec. 24; that Dec. 31 issue will have charts for CONTRIBUTING WRITER both weeks.) We’ll also have our Top 100’s for 2004 in that issue. Tom Mallison PHOTOGRAPHY I don’t know how I’m going to pare down my list – my Top 10 has at Barry Solof least 25 CDs on it – but one that’s in contention is the new Steve Turre al- bum on HighNote, The Sprits Up Above. -

National Academy of Recording Arts & Sciences

NATIONAL ACADEMY OF RECORDING ARTS & SCIENCES, INC.® FINAL NOMINATIONS LIST THE NATIONAL ACADEMY OF RECORDING ARTS & SCIENCES, INC. Final Nominations List 54th Annual GRAMMY® Awards For recordings released during the Eligibility Year October 1, 2010 through September 30, 2011 Note: More or less than 5 nominations in a category is the result of ties. General Field Category 1 Category 2 Record Of The Year Album Of The Year Award to the Artist and to the Producer(s), Recording Engineer(s) Award to the Artist(s) and to the Album Producer(s), Recording and/or Mixer(s), if other than the artist. Engineer(s) and/or Mixer(s) & Mastering Engineer(s), if other than the 1. ROLLING IN THE DEEP artist. Adele 1. 21 Paul Epworth, producer; Tom Elmhirst & Mark Rankin, Adele engineers/mixers Jim Abbiss, Adele, Paul Epworth, Rick Rubin, Fraser T. Smith, Track from: 21 Ryan Tedder & Dan Wilson, producers; Jim Abbiss, Philip Allen, [XL Recordings/Columbia Records] Beatriz Artola, Ian Dowling, Tom Elmhirst, Greg Fidelman, Dan 2. HOLOCENE Parry, Steve Price, Mark Rankin, Andrew Scheps, Fraser T. Smith Bon Iver & Ryan Tedder, engineers/mixers; Tom Coyne, mastering Justin Vernon, producer; Brian Joseph & Justin Vernon, engineer engineers/mixers [XL Recordings/Columbia Records] Track from: Bon Iver 2. WASTING LIGHT [Jagjaguwar] Foo Fighters 3. GRENADE Butch Vig, producer; James Brown & Alan Moulder, Bruno Mars engineers/mixers; Joe LaPorta & Emily Lazar, mastering The Smeezingtons, producers; Ari Levine & Manny Marroquin, engineers engineers/mixers [RCA Records/ -

Recording the Future

Recording The Future A call for a sensible, open-ended advanced audio standard for DVD by George Massenburg So whatʼs DVD, and what does a standard mean to me anyway? Hardly anybody thinks about the creative community anymore when a new technology is being launched. With few exceptions, technological decisions seem now to be made in boardrooms (a.k.a. “artist-free zones”) and artists, or “content providers” as we are now known, are expected to fit creatively within the constraints of formats that are introduced for strictly commercial reasons. This marginalization of artists has not always been the case in the evolution of audio technology. One recalls the important, but suspiciously oft-cited, example of Les Paul and his promotion of eight-track master recorders, and the audiophile contributions to classical recordings by some great conductors -- Leopold Stokowski, Herbert von Karajan and Erich Leinsdorf come quickly to mind. Not to mention the importance that producers like Walt Disney placed on improving sound reproduction for film for purely artistic reasons. But recent trends have headed elsewhere. And to many, the darkest moment in audio technology was the introduction of the digital Compact Disc, mostly for reasons of compromised sound. Audio may, however, be about to embark in a new direction, built upon a new technology called DVD. This so-called Digital Versatile Disc is a higher-density permutation of the CD, and it promises to be the first true digital multimedia format, able to satisfy the demands of the video entertainment producers to replace the VHS videocassette, the computer and video-game communityʼs need for a much-higher-capacity CD-ROM, and the (by comparison much smaller) audio communityʼs interest in tagging along for a number of reasons. -

Acoustic Sounds Catalog Update

Analogue Productions and Quality Record Pressings are proud to announce the newest incarnation of titles to be pressed at 45 RPM on 200-gram vinyl. Ladies and gentlemen: The Doors! Additionally, these will also be available on Multichannel Hybrid SACD. The Doors Strange Days Waiting For The Sun Soft Parade Morrison Hotel L.A. Woman AAPP 74007-45 AAPP 74014-45 AAPP 74024-45 AAPP 75005-45 AAPP 75007-45 AAPP 75011-45 $50.00 $50.00 $50.00 $50.00 $50.00 $50.00 (two 45-RPM LPs) (two 45-RPM LPs) (two 45-RPM LPs) (two 45-RPM LPs) (two 45-RPM LPs) (two 45-RPM LPs) Multichannel Hybrid Multichannel Hybrid Multichannel Hybrid No SACD available No SACD available Multichannel Hybrid SACD SACD SACD for this title for this title SACD CAPP 74007 SA CAPP 74014 SA CAPP 74024 SA CAPP 75011 SA $30.00 $30.00 $30.00 $30.00 Cut from the original analog masters by Doug Sax, with the exception of The Doors, which was made from the best tape copy. Sax and Doors producer/engineer Bruce Botnick went through a meticulous setup to guarantee a positively stunning reissue series. This is an all-tubes process. These masters were recorded on tube equipment and the tape machine used for transfer for these releases is a tube machine, as is the cutting system. Tubes, baby! A truly authentic reissue project. Also available: Mr. Mojo Risin’: The Doors By The Doors The Story Of L.A. Woman The Doors by The Doors – a Featuring exclusive interviews with Ray huge, gorgeous volume in which Manzarek, John Densmore, Robby Krieger the band tells its own story – is colleagues and collaborators, exclusive per- now available.