JPC7.3-Eng.Pdf (7.246Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Côte D'ivoire

CÔTE D’IVOIRE COI Compilation August 2017 United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees Regional Representation for West Africa - RSD Unit UNHCR Côte d’Ivoire UNHCR Regional Representation for West Africa - RSD Unit UNHCR Côte d’Ivoire Côte d’Ivoire COI Compilation August 2017 This report collates country of origin information (COI) on Côte d’Ivoire up to 15 August 2017 on issues of relevance in refugee status determination for Ivorian nationals. The report is based on publicly available information, studies and commentaries. It is illustrative, but is neither exhaustive of information available in the public domain nor intended to be a general report on human-rights conditions. The report is not conclusive as to the merits of any individual refugee claim. All sources are cited and fully referenced. Users should refer to the full text of documents cited and assess the credibility, relevance and timeliness of source material with reference to the specific research concerns arising from individual applications. UNHCR Regional Representation for West Africa Immeuble FAALO Almadies, Route du King Fahd Palace Dakar, Senegal - BP 3125 Phone: +221 33 867 62 07 Kora.unhcr.org - www.unhcr.org Table of Contents List of Abbreviations .............................................................................................................. 4 1 General Information ....................................................................................................... 5 1.1 Historical background ............................................................................................ -

Numéro 2 Juin 2017, ISSN 2521-2125

ADMINISTRATION DE LA REVUE Direction Arsène DJAKO, Professeur à l'Université Alassane OUATTARA (UAO) Secrétariat de rédaction Joseph P. ASSI-KAUDJHIS, Maître de Conférences à l'UAO Konan KOUASSI, Maître-Assistant à l'UAO Dhédé Paul Eric KOUAME, Maître-Assistant à l'UAO Yao Jean-Aimé ASSUE, Maître-Assistant à l'UAO Zamblé Armand TRA BI, Maître-Assistant à l'UAO Kouakou Hermann Michel Kanga, à l’UAO Comité scientifique HAUHOUOT Asseypo Antoine, Professeur Titulaire, Université Félix Houphouët Boigny (Côte d'Ivoire) ALOKO N'Guessan Jérôme, Directeur de Recherches, Université Félix Houphouët Boigny (Côte d'Ivoire) AKIBODÉ Koffi Ayéchoro, Professeur Titulaire, Université de Lomé (Togo) BOKO Michel, Professeur Titulaire, Université Abomey-Calavi (Benin) ANOH Kouassi Paul, Professeur Titulaire, Université Félix Houphouët Boigny (Côte d'Ivoire) MOTCHO Kokou Henri, Professeur Titulaire, Université de Zinder (Niger) DIOP Amadou, Professeur Titulaire, Université Cheick Anta Diop (Sénégal) SOW Amadou Abdoul, Professeur Titulaire, Université Cheick Anta Diop (Sénégal) DIOP Oumar, Professeur Titulaire, Université Gaston Berger Saint-Louis (Sénégal) WAKPONOU Anselme, Professeur HDR, Université de N'Gaoundéré (Cameroun) KOBY Assa Théophile, Maître de Conférences, UFHB (Côte d'Ivoire) SOKEMAWU Kudzo, Maître de Conférences, UL (Togo) 2 EDITORIAL Créée pour participer au développement de la région au Nord du "V baoulé", l’Université de Bouaké aujourd’hui dénommé Université Alassane OUATTARA a profondément été marquée par la longue crise militaro-politique qu’a connu notre pays et dont les effets restent encore gravés dans la mémoire collective. Les enseignants-chercheurs du Département de Géographie, à l’instar de leurs collègues des autres Départements et Facultés de l’Université Alassane OUATTARA, n'ont pas été épargnés par cette crise. -

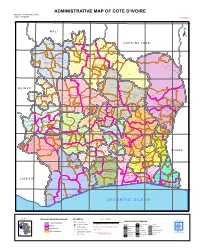

ADMINISTRATIVE MAP of COTE D'ivoire Map Nº: 01-000-June-2005 COTE D'ivoire 2Nd Edition

ADMINISTRATIVE MAP OF COTE D'IVOIRE Map Nº: 01-000-June-2005 COTE D'IVOIRE 2nd Edition 8°0'0"W 7°0'0"W 6°0'0"W 5°0'0"W 4°0'0"W 3°0'0"W 11°0'0"N 11°0'0"N M A L I Papara Débété ! !. Zanasso ! Diamankani ! TENGRELA [! ± San Koronani Kimbirila-Nord ! Toumoukoro Kanakono ! ! ! ! ! !. Ouelli Lomara Ouamélhoro Bolona ! ! Mahandiana-Sokourani Tienko ! ! B U R K I N A F A S O !. Kouban Bougou ! Blésségué ! Sokoro ! Niéllé Tahara Tiogo !. ! ! Katogo Mahalé ! ! ! Solognougo Ouara Diawala Tienny ! Tiorotiérié ! ! !. Kaouara Sananférédougou ! ! Sanhala Sandrégué Nambingué Goulia ! ! ! 10°0'0"N Tindara Minigan !. ! Kaloa !. ! M'Bengué N'dénou !. ! Ouangolodougou 10°0'0"N !. ! Tounvré Baya Fengolo ! ! Poungbé !. Kouto ! Samantiguila Kaniasso Monogo Nakélé ! ! Mamougoula ! !. !. ! Manadoun Kouroumba !.Gbon !.Kasséré Katiali ! ! ! !. Banankoro ! Landiougou Pitiengomon Doropo Dabadougou-Mafélé !. Kolia ! Tougbo Gogo ! Kimbirila Sud Nambonkaha ! ! ! ! Dembasso ! Tiasso DENGUELE REGION ! Samango ! SAVANES REGION ! ! Danoa Ngoloblasso Fononvogo ! Siansoba Taoura ! SODEFEL Varalé ! Nganon ! ! ! Madiani Niofouin Niofouin Gbéléban !. !. Village A Nyamoin !. Dabadougou Sinémentiali ! FERKESSEDOUGOU Téhini ! ! Koni ! Lafokpokaha !. Angai Tiémé ! ! [! Ouango-Fitini ! Lataha !. Village B ! !. Bodonon ! ! Seydougou ODIENNE BOUNDIALI Ponondougou Nangakaha ! ! Sokoro 1 Kokoun [! ! ! M'bengué-Bougou !. ! Séguétiélé ! Nangoukaha Balékaha /" Siempurgo ! ! Village C !. ! ! Koumbala Lingoho ! Bouko Koumbolokoro Nazinékaha Kounzié ! ! KORHOGO Nongotiénékaha Togoniéré ! Sirana -

Linking Social Capital to Therapeutic Practices in Korhogo, Côte D'ivoire

ISSN 1712-8056[Print] Canadian Social Science ISSN 1923-6697[Online] Vol. 17, No. 1, 2021, pp. 91-97 www.cscanada.net DOI:10.3968/12117 www.cscanada.org Linking Social Capital to Therapeutic Practices in Korhogo, Côte d’Ivoire Adiko Adiko Francis[a],*; Ymba Maïmouna[b]; Esso Lasme Jean Charles Emmanuel[c]; Yéo Soungari[d]; Tra Bi Boli Francis[e] [a] Researcher in sociology of health, Centre Ivoirien de Recherches resources” dimensions compared to just over two-thirds Economiques et Sociales (CIRES), Université Félix Houphouët- (69.2%) for those relating to financial resources. Modern Boigny, 08 BP 1295 Abidjan 08; Associated researcher, Centre Suisse de Recherches Scientifiques en Côte d’Ivoire (CSRS), 01 BP 1303 Abidjan medicine (36.1%) and traditional medicine (32.8%) 01, Côte d’Ivoire; are the most dominant in the region. The majority of [b] Teacher-researcher in geography, Institut de Géographie Tropicale households (83.0%) are led to opt for a therapeutic practice (IGT), Université Félix Houphouët-Boigny, 01 BP V 34 Abidjan 01, following discussions with the members of their networks. Côte d’Ivoire; [c] Teacher-researcher in demography, Institut de Géographie Tropicale However, the human, material and financial dimensions (IGT), Université Félix Houphouët-Boigny, 01 BP V 34 Abidjan 01, of social capital have little influence on the choice of Côte d’Ivoire; Associated researcher, Centre Suisse de Recherches therapeutic practices for households. All initiatives aimed Scientifiques en Côte d’Ivoire (CSRS), 01 BP 1303 Abidjan 01, Côte at strengthening solidarity are likely to contribute to d’Ivoire; [d] Teacher-researcher in educational sciences, Institut de Recherches, promoting the health and well-being of disadvantaged d’Expérimentation et d’Enseignement en Pédagogie (IREEP), Université households in situations of socio-political crises. -

ECOWAS Peace & Security Report

ISSUE 10 | OCTOBER 2014 ECOWAS Peace & Security Report Politicians talk past each other as Togo’s 2015 elections approach Introduction While the presidential election in Togo is scheduled for the first quarter of 2015, politicians have still not reached agreement on the implementation of the policy reforms of the 2006 Global Political Agreement. The events of recent months illustrate the seriousness of the political impasse on these issues, which are central to the governance of the country. While the presidential election in Togo is scheduled for the first quarter of 2015, politicians have still not reached agreement on the implementation of the policy reforms of the 2006 Global Political Agreement. The events of recent months illustrate the seriousness of the political impasse on these issues, which are central to the governance of the country. On 30 June 2014, the National Assembly rejected the bill on constitutional and institutional reforms that had been tabled a week earlier by the Government.1 This bill proposed limiting the presidential term to two five-year periods, allowing a two-round presidential election, creating a Senate, reforming the Constitutional Court, defining the prerogatives of the Prime Minister and instituting new eligibility criteria for the presidency. This rejection reflects the failure of the so-called ‘Togo Telecom’ political dialogue, which ended in June 2014. The dialogue failed to reach consensus on the implementation of constitutional and institutional reforms, some of which concerned preparations for the 2015 election. For eight years, the conditions for implementing these reforms have regularly been put back on the agenda without any significant progress being observed. -

Côte D'ivoire

AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT FUND PROJECT COMPLETION REPORT HOSPITAL INFRASTRUCTURE REHABILITATION AND BASIC HEALTHCARE SUPPORT REPUBLIC OF COTE D’IVOIRE COUNTRY DEPARTMENT OCDW WEST REGION MARCH-APRIL 2000 SCCD : N.G. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS, WEIGHTS AND MEASUREMENTS ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS, LIST OF ANNEXES, SUMMARY, CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS BASIC DATA AND PROJECT MATRIX i to xii 1 INTRODUCTION 1 2 PROJECT OBJECTIVES AND DESIGN 1 2.1 Project Objectives 1 2.2 Project Description 2 2.3 Project Design 3 3. PROJECT IMPLEMENTATION 3 3.1 Entry into Force and Start-up 3 3.2 Modifications 3 3.3 Implementation Schedule 5 3.4 Quarterly Reports and Accounts Audit 5 3.5 Procurement of Goods and Services 5 3.6 Costs, Sources of Finance and Disbursements 6 4 PROJECT PERFORMANCE AND RESULTS 7 4.1 Operational Performance 7 4.2 Institutional Performance 9 4.3 Performance of Consultants, Contractors and Suppliers 10 5 SOCIAL AND ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT 11 5.1 Social Impact 11 5.2 Environmental Impact 12 6. SUSTAINABILITY 12 6.1 Infrastructure 12 6.2 Equipment Maintenance 12 6.3 Cost Recovery 12 6.4 Health Staff 12 7. BANK’S AND BORROWER’S PERFORMANCE 13 7.1 Bank’s Performance 13 7.2 Borrower’s Performance 13 8. OVERALL PERFORMANCE AND RATING 13 9. CONCLUSIONS, LESSONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS 13 9.1 Conclusions 13 9.2 Lessons 14 9.3 Recommendations 14 Mrs. B. BA (Public Health Expert) and a Consulting Architect prepared this report following their project completion mission in the Republic of Cote d’Ivoire on March-April 2000. -

Mapping of Groundwater Vulnerability Zones to Pollution in Various Hydrogeological Environments of CôTe D'ivoire By

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 4, Issue 5, May-2013 915 ISSN 2229-5518 Mapping of groundwater vulnerability zones to pollution in various hydrogeological environments of Côte d’Ivoire by DRASTIC method Kan Jean Kouamé, Jean Patrice Jourda , Mahaman Bachir Saley, Serges Kouakou Deh, Abenan Tawa Anani and Jean Biémi Abstract- This study is a synthesis of the work realized by the Remote Sensing and Spatial Analysis Applied to Hydrogeology Laboratory (LATASAH) of the Félix Houphouët-Boigny University of Cocody-Abidjan, concerning the degree of groundwater vulnerability in Côte d’Ivoire. The aimed objective is to elaborate protection tools of groundwater against pollution in various hydrogeological environments. This study uses DRASTIC method. It was realized in Abidjan District (sedimentary environment) and in Korhogo department (crystalline environment). The integration and the overlay of the hydrogeological factors, by running the functionalities of the GIS ArcView, allowed calculating DRASTIC index. A classification of these vulnerabilities index leads to the maps of groundwater vulnerability to pollution. It emerges from the map of Abidjan vulnerability that the degrees of vulnerability are concentrated between moderate and high (88.37%) with 47.33% for the moderate class and 41.04% for the highest. In Korhogo department, the vulnerability map is also dominated by moderate and high vulnerability classes (88%) with 64% for the moderate class and 24% for the highest. These two vulnerability maps were validated by an overlapping of the highest vulnerabilities zones to the zones of high values of nitrate. Index Terms- Côte d’Ivoire, GIS, vulnerability, pollution, DRASTIC, protection, groundwater —————————— —————————— 1. INTRODUCTION The access to the drinking water is an incompressible right The department of Korhogo, located in the North of Côte of every citizen. -

Changes in Vegetation Structure and Carbon Stock in Cashew

International Journal of Research in Agricultural Sciences Volume 8, Issue 2, ISSN (Online): 2348 – 3997 Changes in Vegetation Structure and Carbon Stock in Cashew (Anacardium occidentale L., Anacardiaceae) based Agro-Ecosystem after Clear Forest in the North of Cote D’Ivoire Koffi Kouadio Arsene Dieudonne 1*, Silue Pagadjovongo Adama 2, Kouassi Konan Edouard 1, 3, Coulibaly Tioporo Naminata 1 and Koutouan-Kontchoi Milene Nadege 1, 3 1 Researcher, Felix Houphouet-Boigny University of Abidjan, Cote d’Ivoire. 2 Researcher, Peleforo Gon Coulibaly University of Korhogo, Cote d’Ivoire. 3 Lecturer, West African Science Service Center on Climate Change and Adapted Land Use / African Center of Excellence on Climate Change, Bio-diversity and Sustainable Agriculture (WASCAL / CEA-CCBAB) Cote d’Ivoire. Date of Acceptance (dd/mm/yyyy): 15/02/2021 Date of publication: 20/03/2021 Abstract – The increase in intensive agriculture combined with the problems of climate change are causing considerable degradation of natural ecosystems. Therefore, in order to ensure their protection, it is necessary to find a system that will combine environmental protection and carbon absorption. Thus, the general objective of our research is to understand the role of cashew (Anacardium Occidentale L., Anacardiaceae) plantations of different ages, in the mitigation of the effects of climate change, through the capture of atmospheric carbon in the north of Côte d’Ivoire (Napié in the Korhogo department). The work consisted of evaluating the carbon stock of the clear forest and cashew plantations with their sequestration dynamics at different ages. The carbon stock of the clear forest is 177.854 t/ha. -

Projet D'extension Et De Renforcement Du Reseau De Distribution De La Commune De Katiola

REPUBLIQUE DE COTE D’IVOIRE Public Disclosure Authorized Union – Discipline – Travail -------------------------------- MINISTERE DU PETROLE, DE L’ENERGIE ET DU DEVELOPPEMENT DES ENERGIES RENOUVELABLES --------------------------------- PROJET DE TRANSPORT, DE DISTRIBUTION ET D’ACCES À L’ELECTRICITE (PTDAE) --------------------------------- PROJET D’EXTENSION ET DE RENFORCEMENT DU RESEAU DE DISTRIBUTION DE LA COMMUNE DE KATIOLA Public Disclosure Authorized --------------------------------- Public Disclosure Authorized PLAN D’ACTION DE REINSTALLATION (PAR) DES POPULATIONS AFFECTEES PAR LE PROJET -- RAPPORT PROVISOIRE -- Public Disclosure Authorized -- Mai 2018 -- TABLE DES MATIERES LISTE DES TABLEAUX................................................................................................................................................. 3 LISTE DES PLANCHES ................................................................................................................................................. 3 LISTE DES ABREVIATIONS ........................................................................................................................................ 4 DEFINITIONS DES TERMES ....................................................................................................................................... 5 RESUME EXECUTIF ..................................................................................................................................................... 7 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................................................... -

Les Perspectives De Developpement Du Tourisme Dans Le Departement De Korhogo

ADMINISTRATION DE LA REVUE Direction Arsène DJAKO, Professeur Titulaire à l'Université Alassane OUATTARA (UAO) Secrétariat de rédaction x Joseph P. ASSI-KAUDJHIS, Professeur Titulaire à l'UAO x Konan KOUASSI, Maître-Assistant à l'UAO x Dhédé Paul Eric KOUAME, Maître-Assistant à l'UAO x Yao Jean-Aimé ASSUE, Maître-Assistant à l'UAO x Zamblé Armand TRA BI, Maître-Assistant à l'UAO x Kouakou Hermann Michel KANGA, Assistant à l’UAO Comité scientifique x HAUHOUOT Asseypo Antoine, Professeur Titulaire, Université Félix Houphouët Boigny (Côte d'Ivoire) x ALOKO N'Guessan Jérôme, Directeur de Recherches, Université Félix Houphouët Boigny (Côte d'Ivoire) x AKIBODÉ Koffi Ayéchoro, Professeur Titulaire, Université de Lomé (Togo) x BOKO Michel, Professeur Titulaire, Université Abomey-Calavi (Benin) x ANOH Kouassi Paul, Professeur Titulaire, Université Félix Houphouët Boigny (Côte d'Ivoire) x MOTCHO Kokou Henri, Professeur Titulaire, Université de Zinder (Niger) x DIOP Amadou, Professeur Titulaire, Université Cheick Anta Diop (Sénégal) x SOW Amadou Abdoul, Professeur Titulaire, Université Cheick Anta Diop (Sénégal) x DIOP Oumar, Professeur Titulaire, Université Gaston Berger Saint-Louis (Sénégal) x WAKPONOU Anselme, Professeur HDR, Université de N'Gaoundéré (Cameroun) x KOBY Assa Théophile, Maître de Conférences, UFHB (Côte d'Ivoire) x SOKEMAWU Kudzo, Maître de Conférences, UL (Togo) 2 EDITORIAL La création de RIGES résulte de l’engagement scientifique du Département de Géographie de l’Université Alassane Ouattara à contribuer à la diffusion des savoirs scientifiques. RIGES est une revue généraliste de Géographie dont l’objectif est de contribuer à éclairer la complexité des mutations en cours issues des désorganisations structurelles et fonctionnelles des espaces produits. -

Rapport ENG- Conciliation ITIE Togo 2012

REPUBLIQUE TOGOLAISE EXTRACTIVE INDUSTRIES TRANSPARENCY INITIATIVE EITI TOGO REPORT ON THE RECONCILIATION OF EXTRACTIVE PAYMENTS AND REVENUES FOR THE YEAR 2012 August 2015 This report is established by request of the Multistakeholders Group of EITI Togo. The views expressed in this report are those of the Reconciler and in no way reflect the official opinion of EITI Togo. This report has been prepared solely for use of EITI Togo for the purpose it is intended. Collecte et conciliation des paiements et des recettes du secteur extractif au titre de l’année 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................... 5 Background ................................................................................................................................... 5 Objective ................................................................................................................................... 5 Nature and extent of our work ......................................................................................................... 5 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................... 7 1.1. Revenue from the Extractive Sector ....................................................................................... 7 1.2. Exports ................................................................................................................................... 8 1.3. Report Scope ......................................................................................................................... -

Côte D'ivoire

Niger 8° 7° 6° 5° 4° 3° CÔTE D’IVOIRE The boundaries and names shown and CÔTE the designations used on this map do Sikasso BURKINA National capital D’IVOIRE not imply official endorsement or Regional capital acceptance by the United Nations Bobo-Dioulasso e FASO r Town i 11° Diebougou o 11° Orodara Major airport N B a t a International boundary l MALI g o o L e V e Regional boundary r Banfora a b Main road a Tingrela Railroad Gaoua Goueya San Sokoro kar ani Katoro Kaoura 10° Maniniam Zinguinasso Ouangolodougou 10° Korohara Samatiguila Banda B ma l SAVANES B Bobanie a DENGUELE l c a Moromoro k n Madinani c V Gbeleba o Odienne l Boundiali Ferkessedougou t a I T Seguelo Korhogo r i i e n n g b a Fasselemon o Bouna u GUINEA Bako Paatogo Kiemou Tafire 9° 9° B Gawi Siraodi ou Kineta Fadyadougou Lato M Kakpin a Bandoli Koro r Sonozo a a Kafine oa/Bo Kani h VALLEE DU B o ZANZAN u e Dabakala Boudouyo Santa Touba WORODOUGOU BANDAMA Tanbi BAFING Nandala Mankono Katiola Diaradougou Bondoukau 8° Foungesso 8° C Seguela a v Tanda a Glanle Biankouma Toumbo l l y Beoumi Bouake DIX-HUIT MONTAGNES Zuenoula Sakassou M'Bahiacro Koun Man Vavoua Ba Sunyani Danane N’ZI COMOE HAUT Agnibilekrou Bangolo Daoukro 7° SASSANDRA Bouafle LACS MOYEN 7° COMOE Binhouye Daloa MARAHOUE Yamoussoukro Duekoue Abengourou Dimbokro Sinfra Guiglo Bougouanou Toulepleu Issia Toumodi GHANA Oume MOYENCAVALLY Bebou FROMAGER a i o Zagne Gribouo Gagnoa AGNEBY B n a Tchien Adzope T 6° 6° Agboville Tai Lakota Divo Tiassale Soubre SUD Gueyo SUD BANDAMA COMOE B LIBERIA o u LAGUNES b Aboisso Niebe o Abidjan Grand-Lahou Fish Town BAS SASSANDRA Attoutou Grand-Bassam Braffedon 5° Gazeko 5° Grabo N o n Sassandra o GULF O F GUINEA Barclayville Olodio San-Pedro 0 30 60 90 km Grand Béréby Harper 0 30 60 mi Tabou ATLANTIC OCE A N 8° 7° 6° 5° 4° 3° Map No.