The Archaic Monte Iato: Between Coloniality and Locality �������������������������������������������������������������������� 81

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Flussi Visitatori 2009 Completodef

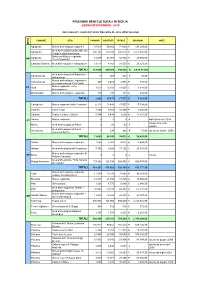

FRUIZIONE BENI CULTURALI IN SICILIA GENNAIO/DICEMBRE 2009 dati elaborati e curati dell' Unita' Operativa III - Area Affari Generali COMUNE SITO PAGANTI GRATUITI TOTALE INCASSO NOTE PROV. Agrigento Museo archeologico regionale 15.838 55.800 71.638 € 138.293,00 Area Archeologica della Valle dei Agrigento 308.745 233.930 542.675 € 2.477.647,00 Templi e della Kolimbetra. Biblioteca Museo regionale Agrigento 15.675 43.087 58.762 € 29.506,00 AG "Luigi Pirandello" Cattolica Eraclea Area archeologica e Antiquarium 13.410 8.163 21.573 € 25.127,00 TOTALI 353.668 340.980 694.648 € 2.670.573,00 Area archeologica di Sabucina e Caltanissetta 13 608 621 € 25,00 Antiquarium Museo archeologico regionale e Caltanissetta 427 2.474 2.901 € 784,00 area archeologica Gibil Gabib Museo regionale e aree CL Gela 1.513 12.154 13.667 € 4.141,50 archeologiche Marianopoli Museo archeologico regionale 140 243 383 € 232,00 TOTALI 2.093 15.479 17.572 € 5.182,50 Caltagirone Museo regionale della Ceramica 6.111 11.446 17.557 € 17.794,00 Catania Casa Verga 1.266 9.203 10.469 € 3.494,00 Catania Teatro romano e Odeon 4.244 3.414 7.658 € 11.522,00 CT Adrano Museo regionale 0 0 0 € - biglietteria non attiva chiuso solo visite Mineo Area archeologica di Palikè 0 93 93 € - guidate Area archeologica di Santa Acicastena 8 234 242 € 15,00 aperto da ottobre 2009 Venera al Pozzo TOTALI 11.629 24.390 36.019 € 32.825,00 Aidone Museo archeologico regionale 1.265 3.562 4.827 € 3.649,00 Aidone Area archeologica di Morgantina 7.300 9.826 17.126 € 21.241,00 Museo archeologico regionale di -

A Dynamic Analysis of Tourism Determinants in Sicily

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by NORA - Norwegian Open Research Archives A Dynamic Analysis of Tourism Determinants in Sicily Davide Provenzano Master Programme in System Dynamics Department of Geography University of Bergen Spring 2009 Acknowledgments I am grateful to the Statistical Office of the European Communities (EUROSTAT); the Italian National Institute of Statistics (ISTAT), the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO); the European Climate Assessment & Dataset (ECA&D 2009), the Statistical Office of the Chamber of Commerce, Industry, Craft Trade and Agriculture (CCIAA) of Palermo; the Italian Automobile Club (A.C.I), the Italian Ministry of the Environment, Territory and Sea (Ministero dell’Ambiente e della Tutela del Territorio e del Mare), the Institute for the Environmental Research and Conservation (ISPRA), the Regional Agency for the Environment Conservation (ARPA), the Region of Sicily and in particular to the Department of the Environment and Territory (Assessorato Territorio ed Ambiente – Dipartimento Territorio ed Ambiente - servizio 6), the Department of Arts and Education (Assessorato Beni Culturali, Ambientali e P.I. – Dipartimento Beni Culturali, Ambientali ed E.P.), the Department of Communication and Transportation (Assessorato del Turismo, delle Comunicazioni e dei Trasporti – Dipartimento dei Trasporti e delle Comunicazioni), the Department of Tourism, Sport and Culture (Assessorato del Turismo, delle Comunicazioni e dei Trasporti – Dipartimento Turismo, Sport e Spettacolo), for the high-quality statistical information service they provide through their web pages or upon request. I would like to thank my friends, Antonella (Nelly) Puglia in EUROSTAT and Antonino Genovesi in Assessorato Turismo ed Ambiente – Dipartimento Territorio ed Ambiente – servizio 6, for their direct contribution in my activity of data collecting. -

Scheda Progetto Beni Culturali

INQUADRAMENTO TERRITORIALE E SOCIO ECONOMICO L’intervento si snoda pressoché in tutta la Regione Sicilia interessando Novantacinque siti territorialmente riconducibili a due macro ambiti territoriali: urbano ed extraurbano. Tra i siti collocati in ambito extraurbano ritroviamo essenzialmente gli «antiquaria», connessi alle aree archeologiche, che, in alcuni casi, sono a loro volta costituiti da insiemi di edifici dalle caratteristiche architettoniche e morfologiche eterogenee. Per non appesantire l’esposizione degli interventi tali fattispecie sono state trattate nell’ambito del macro sito archeologico. Esemplificativo il caso del Parco archeologico di Selinunte, al numero trenta della proposta, che annovera oltre venti piccoli edifici dislocati «a random» nel territorio del Parco, trattati in maniera aggregata nel Progetto di FTE specifico del già citato sito 30 Parco archeologico di Selinunte. Individuazione dei siti oggetto di intervento indicati per provincia di appartenenza. Provincia di Palermo 26 siti Codice numerico proposta Denominazione sito 1 Albergo delle Povere 2 Biblioteca Centrale Palermo 3 Castello Zisa 4 Dipartimento BBCC Palermo 5 Palazzo Abatellis 6 Palazzo Riso 8 Castello Maredolce / Palazzo della Favara 14 Castello a mare 63 Chiostro di San Giovanni degli Eremiti 64 Convento della Magione 65 Palazzo Ajutamicristo 67 Palazzo Mirto 68 Soprintendenza Mare 81 Casina Cinese 82 Castello della Cuba 83 Museo Regionale Antonino Salinas 84 Necropoli Punica 85 Oratorio dei Bianchi 86 Palazzo Montalbo 87 Villino Florio 7 Chiostro -

DIMAURO ETTORE Luogo Di Nascita

CURRICULUM VITAE DATI ANAGRAFICI Cognome e nome: DIMAURO ETTORE Luogo di nascita: Data di nascita: Qualifica: DIRIGENTE DI TERZA FASCIA – ARCHITETTO Incarico attuale: DIRIGENTE RESPONSABILE UNITA’ OPERATIVA V – Tutela e Valorizzazione Beni Archeologici - (Incarico dal 20/09/2004 al 2010) Sede di lavoro: SOPRINTENDENZA BB.CC.AA. DI CALTANISSETTA dal 01 MARZO 1991 Casella di posta: Residenza: Telefono ufficio: Fax ufficio: Cod. Fiscale: Titolo di studio: Laurea in Architettura conseguita presso l’Università degli Studi di Palermo nel 1984 Sintesi esperienze professionali: 1984 - Si laurea presso la Facoltà di Architettura di Palermo. Nello stesso anno apre uno studio di progettazione architettonica a Caltanissetta e forma il gruppo “Itaca Architetti Associati”. 1986 - Partecipa al "Concorso di idee per la progettazione del Santuario della Madonna della Cava a Marsala" ottenendo una segnalazione. 1991– Assume il ruolo di Dirigente presso la Soprintendenza ai Beni Culturali ed Ambientali di Caltanissetta, dove svolge ininterrottamente il proprio ruolo nell’ambito del Servizio per i Beni Architettonici Paesistici, Naturali, Naturalistici ed Urbanistici fino al 2004. Dal 2004 è nominato Dirigente Responsabile dell’Unità Operativa V – “Tutela e valorizzazione dei Beni Archeologici”, coordinando altresì il personale di custodia dei Musei Archeologici di Caltanissetta e Marianopoli. 1 1991 – E’ invitato ad esporre i propri progetti di architettura, alla Biennale di Venezia, Padiglione Italia, in occasione della V Mostra Internazionale di Architettura. 1993 - Partecipa al "Concorso Nazionale Una via tre piazze a Gela" ottenendo una menzione speciale. 1993-1994 –E’ Consigliere dell’Ordine degli Architetti di Caltanissetta e delegato alla Commissione Cultura istituita presso la Consulta Regionale degli Architetti. 1995-1999 - E’ Docente di Paesaggistica e di Teoria del Restauro nonchè Coordinatore del Corso di Specializzazione post-diploma tenuto all’ I.T.G. -

(12) Sicily Index

INDEXRUNNING HEAD VERSO PAGES 527 Explanatory or more detailed references (where there are many) are given in bold. Numbers in italics are picture references. Dates are given for all artists, architects and sculptors. A Agrippa 468 Acate 319 Aidone 280 Aci Castello 421 Alagona, Archbishop 344 Acireale 419 Alcamo 145, 519 Acitrezza 420, 517 Alcantara Gorge 465 Acquacalda 479 Alcara Li Fusi 488 Acquaviva Platani 245 Alcibiades 402 Acquedolci 488 Alexander II, Pope 268, 289 Acrae 371, 372 Alexis of Tarentum 509 Acitrezza 517 Alì 467 Acron, physician 193 Alì Terme 467 Adelaide, Queen 281, 290, 484, 487, 488 Alì, Luciano (fl. late 17C–early 18C) 345 Adrano 412 Alì, Salvatore (fl. late 18C) 312 Aeolian Islands 277, 472–483 Alia 87 Aeschylus 248, 338, 357, 396, 410 Alibrandi, Girolamo (1470–1524) 414, St Agatha 396, 397, tomb 406 415, 450, 475 Agathocles 10, 84, 90, 143, 165, 250, Alicudi 481 339, 445 Al-Idrisi 510 Agira 283 Acitrezza 517 Agrigento 9, 193–211, 247, 248, 250, Amato, Andrea (fl. 1720–35) 401, 405, 353, 515 426 Duomo 195 Amato, Giacomo (1643–1732) 15, 43, Garden of Kolymbetra 204 46, 50 Museo Archeologico 204, 207 Amato, Paolo (1634–1714) 44, 54, 106, Museo Civico 194 170 Sanctuary of Demeter 209 Ambrogio da Como (fl. 1471–73) 91 Sanctuary of the Chthonic Divinities Amico, Giovanni Biagio (1684–1754) 53, 203 128, 131, 137, 147, 148, 156, 226 Temple of Asclepios 209 Anapo Valley 374 Temple of Castor and Pollux 203 Andrault, Michel (b. 1926) 354 Temple of Concord 199, 200 Andrea da Salerno (also known as Andrea Temple of Hephaistos 209, 210 Sabatini; c. -

La Sicilia Romana Tra Repubblica E Alto Impero

Μεσογεια III Convegno annuale di studi sulla Sicilia antica SiciliAntica Regione Siciliana Associazione per la Tutela e la Valorizzazione Assessorato dei Beni Culturali dei Beni Culturali e Ambientali ed Ambientali Sede di Caltanissetta La Sicilia romana tra Repubblica e Alto Impero ATTI DEL CONVEGNO DI STUDI a cura di Calogero Miccichè Simona Modeo Luigi Santagati Caltanissetta 20 - 21 maggio 2006 1 In copertina: Museo Archeologico Regionale “A. Salinas” di Palermo, rilievo di prove- nienza incerta (Raffadali o Marina di Caronia) (da G. Pugliese Carratelli, a cura di, Princeps urbium, Milano 1991). La Sicilia romana tra Repubblica e Alto Impero : atti del convegno di studi, Caltanissetta 20-21 maggio 2006 / a cura di Calogero Miccichè, Simona Modeo, Luigi Santagati. – Caltanissetta : Siciliantica, 2007. 1. Sicilia – Storia – Sec. 3. a. C.-2. d.C. – Congressi – 2006. 2. Congressi – Caltanissetta – 2006. I. Miccichè, Calogero. II. Modeo, Simona. III. Santagati, Luigi. 937.8 CDD-21 SBN Pal0209275 CIP - Biblioteca centrale della Regione siciliana “Alberto Bombace” 2 SiciliAntica Sede di Caltanissetta Convegno di Studi La Sicilia romana tra Repubblica e Alto Impero Auditorium della Biblioteca Comunale Luciano Scarabelli Il Convegno è stato organizzato in collaborazione con la Soprintendenza per i Beni Culturali ed Ambientali di Caltanissetta Con il patrocinio dell’Assessorato Regionale per i Beni Culturali ed Ambientali della Provincia di Caltanissetta – Assessorato alla Cultura del Comune di Caltanissetta – Assessorato all’ Identità e Futuro dell’AAPIT di Caltanissetta e con il contributo della Banca di Credito Cooperativo San Michele di Caltanissetta e Pietraperzia della Finsea di Caltanissetta dell’AXA Assicurazioni ed Investimenti di Caltanissetta di Zirilli - Caltanissetta Sabato 20 maggio Sabato 21 maggio Ore 9,30 Ore 9,30 – 12,30 Presentazione del convegno di Studi Relazioni Simona Modeo Ore 15,30 – 17,45 Presidente di SiciliAntica - Sede di Caltanissetta Relazioni Alessandro Pagano Ore 17,45 Assessore Regionale per i BB.CC.AA. -

Provvedimenti (Dirigenti) - Art

Provvedimenti (dirigenti) - Art. 23, Decreto Legislativo n. 33 del 14 marzo 2013 Estremi del provvedimento Soggetto emanante n° Data Contenuto lettera comma 1, art. 23 Oggetto Eventuale spesa prevista Estremi documenti relativi al procedimento Area AA.GG. 52115 27/10/2015 Rdo n.966558 MEPA Cap.376510 - Ripristino illuminazione Albergo delle Povere - Ditta ABS € 3.333,33 Richiesta preventivo di spesa nota prot.n.59467 del 3.12.2015 di Sciuto Clemente Area AA.GG. 5580 16/11/2015 nota prot.n. 55772/15 D.A. n.80/08 art.4 comma 4 Cap. 376506 - Fornitura materiale igienico-sanitario per il Dipartimento € 1.229,76 Richiesta preventivi di spesa nota prot.n.48094 del 7.10.2016 BB.CC. e I.S. e Albergo delle Povere - Ditta Nasta Area AA.GG. 64438 31/12/2015 Rdo n. 1050798 MEPA Cap. 376507 - Servizi postali per 2 mesi per il Dipartimento BB.CC. e € 7.308,41 Autorizzazione a procedere con D.A. n.80/08 prot.n.11923/15 I.S. Area AA.GG. 64425 31/12/2015 Rdo n.889470 MEPA Cap. 376506 - Proroga servizi di sanificazione e sanitizzazione nel € 4.961,84 Autorizzazione proroga servizio di pulizia prot.n. 64412 del 31.12.2015 Dipartimento BB.CC. e I.S.e siti dipendenti- Ditta La Politutto BIBL.REG.MESSINA 29069 19/06/2015 CONTRATTO D RESTAURO LIBRI € 2.167,15 Contr.Prot.2110 del 27.10.15; Atto Agg. Prot. 2191 del 29.10.15; BIBL.REG.MESSINA 64412 07/12/2015 LETTERA D'ORDINE D EUROSERVICE GROUP € 3.965,14 Prot. -

Explanatory Or More Detailed References (Where There Are Many), Or References to Places Where an Artist’S Work Is Best Represented, Are Given in Bold

550 Index Explanatory or more detailed references (where there are many), or references to places where an artist’s work is best represented, are given in bold. Numbers in italics are picture references. Dates are given for all artists, architects and sculptors with works referenced in this guide. Ancient names are rendered in italics, as are works of art. Abakainon, ancient city 474 Agrigento contd Acate 326 Grotta Fragapane 201 Accommodation 515 Hellenistic and Roman district 212 Aci Castello 426 Kolymbethra Garden 208 Acireale 424 Living Museum of the Almond Tree 213 Acitrezza 426 Lower agora 206 Acquaviva Platani 254 Museo Civico 215 Acquedolci 482 Museo Diocesano 216 Addaura Caves 73; (finds from) 64 Oratory of Phalaris 211 Adelaide, wife of Roger I 300, 481, 482 Pezzino Necropolis 214 (tomb of) 477 Pinacoteca Palazzo dei Filippini 215 Adrano 419; (finds from) 360 S. Biagio 212 Adranon, ancient city 223 S. Maria dei Greci 215 Aegadian Islands 180ff S. Nicola 211 Aeneas, legends concerning 136, 143, 144, Sanctuary of Asklepios 213 147 Sanctuary of Demeter 212 Aeolian Islands 484 Sanctuary of the Chthonic Divinities 207 Aeschylus 256, 257, 344, 364, 400, 415 Temple of Castor and Pollux 207 Agatha, St 409, 410, 411 (reliquaries of) Temple of Concord 198, 201, 204 404 Temple of Hephaistos 214 Agathocles, tyrant of Syracuse 11, 95, 100, Temple of Hera 200 147, 173, 259, 344, 448 Temple of Herakles 205 Agira 294 Temple of Zeus 205, 207, 209 Agrigento 199ff; (finds from) 208, 360 Tomb of Theron 213 Aqueduct of Phaiax 208, 215 Upper agora -

Flussi Visitatori 2010 Completo

FRUIZIONE BENI CULTURALI IN SICILIA GENNAIO/DICEMBRE 2010 COMUNE SITO PAGANTI GRATUITI TOTALE INCASSO NOTE PROV. Agrigento Museo archeologico regionale 16.308 48.864 65.172 € 144.811,00 Area archeologica della Valle dei Agrigento 313.121 230.747 543.868 € 2.753.220,00 Templi e della Kolimbetra. Biblioteca Museo regionale "Luigi Agrigento 14.976 33.904 48.880 € 46.033,00 AG Pirandello" Cattolica Eraclea Area archeologica e Antiquarium 13.972 8.332 22.304 € 42.503,00 TOTALI 358.377 321.847 680.224 € 2.986.567,00 Complesso Minerario Trabia Caltanissetta 420 218 638 € 722,00 Tallarita Area archeologica e Antiquarium Caltanissetta 20 253 273 € 27,00 di Sabucina Museo archeologico regionale e Caltanissetta 685 1.250 1.935 € 1.354,00 CL area archeologica Gibil Gabib Museo regionale e aree Gela 3.059 9.430 12.489 € 5.976,00 archeologiche Marianopoli Museo archeologico regionale 124 333 457 € 201,00 TOTALI 4.308 11.484 15.792 € 8.280,00 Caltagirone Museo regionale della Ceramica 6.064 10.343 16.407 € 20.278,00 Catania Casa Verga 1.179 7.215 8.394 € 3.470,00 Catania Teatro romano e Odeon 3.810 16.916 20.726 € 10.084,00 CT Adrano Museo regionale 115 458 573 € 385,00 Mineo Area archeologica di Palikè 12 210 222 € 24,00 Apertura a maggio Area archeologica di Santa Acicastena 58 740 798 € 112,00 Venera al Pozzo TOTALI 11.238 35.882 47.120 € 34.353,00 Centuripe Museo archeologico regionale 1.157 1.842 2.999 € 2.247,00 Aidone Museo archeologico regionale 3.804 5.312 9.116 € 11.484,00 Aidone Area archeologica di Morgantina 8.869 10.741 19.610 € 29.746,00 -

Coins of Punic Sicily. Part 2, Carthage Series I

Coins of punic sicily. Part 2, Carthage Series I Autor(en): Jenkins, G. Kenneth. Objekttyp: Article Zeitschrift: Schweizerische numismatische Rundschau = Revue suisse de numismatique = Rivista svizzera di numismatica Band (Jahr): 53 (1974) PDF erstellt am: 08.10.2021 Persistenter Link: http://doi.org/10.5169/seals-174152 Nutzungsbedingungen Die ETH-Bibliothek ist Anbieterin der digitalisierten Zeitschriften. Sie besitzt keine Urheberrechte an den Inhalten der Zeitschriften. Die Rechte liegen in der Regel bei den Herausgebern. Die auf der Plattform e-periodica veröffentlichten Dokumente stehen für nicht-kommerzielle Zwecke in Lehre und Forschung sowie für die private Nutzung frei zur Verfügung. Einzelne Dateien oder Ausdrucke aus diesem Angebot können zusammen mit diesen Nutzungsbedingungen und den korrekten Herkunftsbezeichnungen weitergegeben werden. Das Veröffentlichen von Bildern in Print- und Online-Publikationen ist nur mit vorheriger Genehmigung der Rechteinhaber erlaubt. Die systematische Speicherung von Teilen des elektronischen Angebots auf anderen Servern bedarf ebenfalls des schriftlichen Einverständnisses der Rechteinhaber. Haftungsausschluss Alle Angaben erfolgen ohne Gewähr für Vollständigkeit oder Richtigkeit. Es wird keine Haftung übernommen für Schäden durch die Verwendung von Informationen aus diesem Online-Angebot oder durch das Fehlen von Informationen. Dies gilt auch für Inhalte Dritter, die über dieses Angebot zugänglich sind. Ein Dienst der ETH-Bibliothek ETH Zürich, Rämistrasse 101, 8092 Zürich, Schweiz, www.library.ethz.ch http://www.e-periodica.ch G.KENNETH JENKINS COINS OF PUNIC SICILY Part 2 CARTHAGE SERIES I Introduction This instalment of the publication started in SNR 50, 1971, 25 ff. will cover only the first series of the regular issues of Carthage. It is a small and compact series which stands somewhat apart from the rest of the coinage both typologically and otherwise, and it can therefore conveniently be treated in isolation. -

Les Carnets De L'acost, 17

Les Carnets de l’ACoSt Association for Coroplastic Studies 17 | 2018 Varia Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/acost/1085 DOI : 10.4000/acost.1085 ISSN : 2431-8574 Éditeur ACoSt Référence électronique Les Carnets de l’ACoSt, 17 | 2018 [En ligne], mis en ligne le 10 avril 2018, consulté le 24 septembre 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/acost/1085 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/acost.1085 Ce document a été généré automatiquement le 24 septembre 2020. Les Carnets de l'ACoSt est mis à disposition selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. 1 SOMMAIRE The P.A. Sabouroff Collection of Ancient Terracottas from The State Hermitage Museum Elena Khodza Solid items made to break, or breakable items made to last? The case of Minoan peak sanctuary figurines Céline Murphy Terracotta Figures, Figurines, and Plaques from the Anavlochos, Crete. Florence Gaignerot-Driessen Terracotta Figurines and the Acrolithic Statues of Demeter and Kore from Morgantina Laura Maniscalco Works in Progress Modelling Regional Networks and Local Adaptation: West-Central Sicilian Relief Louteria Andrew Farinholt Ward Two Collaborative Projects for Coroplastic Research, IV. The Work of the Academic Years 2016–2017 Arthur Muller et Jaimee Uhlenbrock At the Museums La collection des figurines en terre cuite du Musée National d’Athènes : formation et muséographie Christina Avronidaki et Evangelos Vivliodetis Due mostre a Catania: un’occasione per avvicinare i ragazzi al mondo dell’archeologia Antonella Pautasso Figure d’Argilla. Laboratorio di archeologia sperimentale Antonella Pautasso Book Reviews Terrakotten aus Beit Nattif. -

Histoire Des Collections Numismatiques Et Des Institutions Vouées À La Numismatique

44 HISTOIRE DES COLLECTIONS NUMISMATIQUES ET DES INSTITUTIONS VOUÉES À LA NUMISMATIQUE Lavinia Sole COLLEZIONI NUMISMATICHE DEI MUSEI DELLA PROVINCIA DI CALTANISSETTA Le principali collezioni numismatiche del territorio della provincia di Cal- tanissetta sono conservate in tre musei ed un antiquarium, tutti aperti alla pubblica fruizione e recentemente rinnovati nei percorsi, nella didattica e nei contenuti. Si tratta del Museo Archeologico Regionale di Gela, del Mu- seo Regionale Interdisciplinare di Caltanissetta, del Museo Archeologico Regionale di Marianopoli e dell’Antiquarium archeologico comunale “A. Petyx” di Milena. La raccolta numismatica del Museo Archeologico Regionale di Gela, Istituto periferico autonomo dell’Assessorato Regionale dei Beni Culturali e dell’Identità Siciliana, è costituita da monete quantitativamente superiori a quelle delle altre collezioni della provincia. In totale infatti il Medagliere annovera circa 2000 monete, di cui molte sono di età greca (in esposizione 770 ess. circa), una piccola parte appartiene al periodo romano-repubblicano (60 ess. circa; in esposizione 15 ess.), un gruppo più numeroso è di età romano-imperiale (320 ess. circa; in esposizione 83 ess.), mentre un nucleo minoritario si divide fra i periodi bizantino (35 ess. in esposizione), medievale (160 ess. circa; 11 ess. in esposizione) e moderno (35 ess. in esposizione). La formazione della collezione numismatica risale agli anni Cinquanta del secolo scorso, all’epoca dei primi scavi sistematici condotti nel sito della città di Gela e del suo immediato entroterra dalla Soprintendenza compe- tente sul territorio, che allora aveva sede ad Agrigento1. Gli scavi che pro- gressivamente si effettuarono nel territorio incrementarono ulteriormente 1 Sulla formazione del medagliere, si vedano: P.