Les Carnets De L'acost, 17

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Flussi Visitatori 2009 Completodef

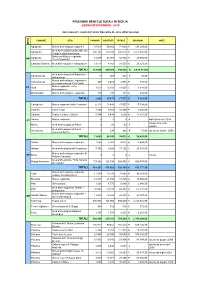

FRUIZIONE BENI CULTURALI IN SICILIA GENNAIO/DICEMBRE 2009 dati elaborati e curati dell' Unita' Operativa III - Area Affari Generali COMUNE SITO PAGANTI GRATUITI TOTALE INCASSO NOTE PROV. Agrigento Museo archeologico regionale 15.838 55.800 71.638 € 138.293,00 Area Archeologica della Valle dei Agrigento 308.745 233.930 542.675 € 2.477.647,00 Templi e della Kolimbetra. Biblioteca Museo regionale Agrigento 15.675 43.087 58.762 € 29.506,00 AG "Luigi Pirandello" Cattolica Eraclea Area archeologica e Antiquarium 13.410 8.163 21.573 € 25.127,00 TOTALI 353.668 340.980 694.648 € 2.670.573,00 Area archeologica di Sabucina e Caltanissetta 13 608 621 € 25,00 Antiquarium Museo archeologico regionale e Caltanissetta 427 2.474 2.901 € 784,00 area archeologica Gibil Gabib Museo regionale e aree CL Gela 1.513 12.154 13.667 € 4.141,50 archeologiche Marianopoli Museo archeologico regionale 140 243 383 € 232,00 TOTALI 2.093 15.479 17.572 € 5.182,50 Caltagirone Museo regionale della Ceramica 6.111 11.446 17.557 € 17.794,00 Catania Casa Verga 1.266 9.203 10.469 € 3.494,00 Catania Teatro romano e Odeon 4.244 3.414 7.658 € 11.522,00 CT Adrano Museo regionale 0 0 0 € - biglietteria non attiva chiuso solo visite Mineo Area archeologica di Palikè 0 93 93 € - guidate Area archeologica di Santa Acicastena 8 234 242 € 15,00 aperto da ottobre 2009 Venera al Pozzo TOTALI 11.629 24.390 36.019 € 32.825,00 Aidone Museo archeologico regionale 1.265 3.562 4.827 € 3.649,00 Aidone Area archeologica di Morgantina 7.300 9.826 17.126 € 21.241,00 Museo archeologico regionale di -

The Coinage of Akragas C

ACTA UNIVERSITATIS UPSALIENSIS Studia Numismatica Upsaliensia 6:1 STUDIA NUMISMATICA UPSALIENSIA 6:1 The Coinage of Akragas c. 510–406 BC Text and Plates ULLA WESTERMARK I STUDIA NUMISMATICA UPSALIENSIA Editors: Harald Nilsson, Hendrik Mäkeler and Ragnar Hedlund 1. Uppsala University Coin Cabinet. Anglo-Saxon and later British Coins. By Elsa Lindberger. 2006. 2. Münzkabinett der Universität Uppsala. Deutsche Münzen der Wikingerzeit sowie des hohen und späten Mittelalters. By Peter Berghaus and Hendrik Mäkeler. 2006. 3. Uppsala universitets myntkabinett. Svenska vikingatida och medeltida mynt präglade på fastlandet. By Jonas Rundberg and Kjell Holmberg. 2008. 4. Opus mixtum. Uppsatser kring Uppsala universitets myntkabinett. 2009. 5. ”…achieved nothing worthy of memory”. Coinage and authority in the Roman empire c. AD 260–295. By Ragnar Hedlund. 2008. 6:1–2. The Coinage of Akragas c. 510–406 BC. By Ulla Westermark. 2018 7. Musik på medaljer, mynt och jetonger i Nils Uno Fornanders samling. By Eva Wiséhn. 2015. 8. Erik Wallers samling av medicinhistoriska medaljer. By Harald Nilsson. 2013. © Ulla Westermark, 2018 Database right Uppsala University ISSN 1652-7232 ISBN 978-91-513-0269-0 urn:nbn:se:uu:diva-345876 (http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:uu:diva-345876) Typeset in Times New Roman by Elin Klingstedt and Magnus Wijk, Uppsala Printed in Sweden on acid-free paper by DanagårdLiTHO AB, Ödeshög 2018 Distributor: Uppsala University Library, Box 510, SE-751 20 Uppsala www.uu.se, [email protected] The publication of this volume has been assisted by generous grants from Uppsala University, Uppsala Sven Svenssons stiftelse för numismatik, Stockholm Gunnar Ekströms stiftelse för numismatisk forskning, Stockholm Faith and Fred Sandstrom, Haverford, PA, USA CONTENTS FOREWORDS ......................................................................................... -

Exploring Eastern Crete

Exploring eastern Crete Plan Days 4 First time in Crete, I guess I should start from the eastern part. A bit of hiking, Chrissi island and Zakro! By: Bonnie_EN PLAN SUMMARY Day 1 1. Ierapetra About region/Main cities & villages 2. Chrissi Islet Nature/Beaches 3. Belegrina Nature/Beaches Day 2 1. Orino Gorge Nature/Gorges 2. Ammoudi Nature/Beaches 3. Makrigialos Nature/Beaches Day 3 1. Zakros Minoan Palace Culture/Archaelogical sites 2. Kato Zakros Nature/Beaches 3. Dead’s Gorge Nature/Gorges Day 4 1. Vai Nature/Beaches 2. Agios Nikolaos About region/Main cities & villages WonderGreece.gr - Bon Voyage 1 Day 1 1. Ierapetra Απόσταση: Start - About region / Main cities & villages Χρόνος: - GPS: N35.0118955, W25.740745199999992 Note: Breakfast and buy supplies for the excursion to Chrissi 2. Chrissi Islet Απόσταση: not available - Nature / Beaches Χρόνος: - GPS: N34.874162, W25.69242399999996 Note: It looks more than great, don't forget my camera 3. Belegrina Απόσταση: not available - Nature / Beaches Χρόνος: - GPS: N34.876695270466335, W25.723740148779257 WonderGreece.gr - Bon Voyage 2 Day 2 1. Orino Gorge Απόσταση: Start - Nature / Gorges Χρόνος: - GPS: N35.06482450148083, W25.919971336554 Note: food for picnic 2. Ammoudi Απόσταση: by car 17.9km Nature / Beaches Χρόνος: 25′ GPS: N35.02149753640775, W26.01497129345705 Note: I would definitely wish to reach this beach 3. Makrigialos Απόσταση: by car 4.9km Nature / Beaches Χρόνος: 05′ GPS: N35.03926672571038, W25.976804824914552 Note: alternative if there is not enough time to go to Ammoudi WonderGreece.gr - Bon Voyage 3 Day 3 1. Zakros Minoan Palace Location: Zakros Culture / Archaelogical sites Contact: Tel: (+30) 28410 22462, 24943, 22382 Απόσταση: Note: How could I not go Start - Χρόνος: - GPS: N35.098203523045854, W26.261405940008558 2. -

A Dynamic Analysis of Tourism Determinants in Sicily

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by NORA - Norwegian Open Research Archives A Dynamic Analysis of Tourism Determinants in Sicily Davide Provenzano Master Programme in System Dynamics Department of Geography University of Bergen Spring 2009 Acknowledgments I am grateful to the Statistical Office of the European Communities (EUROSTAT); the Italian National Institute of Statistics (ISTAT), the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO); the European Climate Assessment & Dataset (ECA&D 2009), the Statistical Office of the Chamber of Commerce, Industry, Craft Trade and Agriculture (CCIAA) of Palermo; the Italian Automobile Club (A.C.I), the Italian Ministry of the Environment, Territory and Sea (Ministero dell’Ambiente e della Tutela del Territorio e del Mare), the Institute for the Environmental Research and Conservation (ISPRA), the Regional Agency for the Environment Conservation (ARPA), the Region of Sicily and in particular to the Department of the Environment and Territory (Assessorato Territorio ed Ambiente – Dipartimento Territorio ed Ambiente - servizio 6), the Department of Arts and Education (Assessorato Beni Culturali, Ambientali e P.I. – Dipartimento Beni Culturali, Ambientali ed E.P.), the Department of Communication and Transportation (Assessorato del Turismo, delle Comunicazioni e dei Trasporti – Dipartimento dei Trasporti e delle Comunicazioni), the Department of Tourism, Sport and Culture (Assessorato del Turismo, delle Comunicazioni e dei Trasporti – Dipartimento Turismo, Sport e Spettacolo), for the high-quality statistical information service they provide through their web pages or upon request. I would like to thank my friends, Antonella (Nelly) Puglia in EUROSTAT and Antonino Genovesi in Assessorato Turismo ed Ambiente – Dipartimento Territorio ed Ambiente – servizio 6, for their direct contribution in my activity of data collecting. -

ANCIENT TERRACOTTAS from SOUTH ITALY and SICILY in the J

ANCIENT TERRACOTTAS FROM SOUTH ITALY AND SICILY in the j. paul getty museum The free, online edition of this catalogue, available at http://www.getty.edu/publications/terracottas, includes zoomable high-resolution photography and a select number of 360° rotations; the ability to filter the catalogue by location, typology, and date; and an interactive map drawn from the Ancient World Mapping Center and linked to the Getty’s Thesaurus of Geographic Names and Pleiades. Also available are free PDF, EPUB, and MOBI downloads of the book; CSV and JSON downloads of the object data from the catalogue and the accompanying Guide to the Collection; and JPG and PPT downloads of the main catalogue images. © 2016 J. Paul Getty Trust This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, CA 94042. First edition, 2016 Last updated, December 19, 2017 https://www.github.com/gettypubs/terracottas Published by the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles Getty Publications 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 500 Los Angeles, California 90049-1682 www.getty.edu/publications Ruth Evans Lane, Benedicte Gilman, and Marina Belozerskaya, Project Editors Robin H. Ray and Mary Christian, Copy Editors Antony Shugaar, Translator Elizabeth Chapin Kahn, Production Stephanie Grimes, Digital Researcher Eric Gardner, Designer & Developer Greg Albers, Project Manager Distributed in the United States and Canada by the University of Chicago Press Distributed outside the United States and Canada by Yale University Press, London Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: J. -

Scheda Progetto Beni Culturali

INQUADRAMENTO TERRITORIALE E SOCIO ECONOMICO L’intervento si snoda pressoché in tutta la Regione Sicilia interessando Novantacinque siti territorialmente riconducibili a due macro ambiti territoriali: urbano ed extraurbano. Tra i siti collocati in ambito extraurbano ritroviamo essenzialmente gli «antiquaria», connessi alle aree archeologiche, che, in alcuni casi, sono a loro volta costituiti da insiemi di edifici dalle caratteristiche architettoniche e morfologiche eterogenee. Per non appesantire l’esposizione degli interventi tali fattispecie sono state trattate nell’ambito del macro sito archeologico. Esemplificativo il caso del Parco archeologico di Selinunte, al numero trenta della proposta, che annovera oltre venti piccoli edifici dislocati «a random» nel territorio del Parco, trattati in maniera aggregata nel Progetto di FTE specifico del già citato sito 30 Parco archeologico di Selinunte. Individuazione dei siti oggetto di intervento indicati per provincia di appartenenza. Provincia di Palermo 26 siti Codice numerico proposta Denominazione sito 1 Albergo delle Povere 2 Biblioteca Centrale Palermo 3 Castello Zisa 4 Dipartimento BBCC Palermo 5 Palazzo Abatellis 6 Palazzo Riso 8 Castello Maredolce / Palazzo della Favara 14 Castello a mare 63 Chiostro di San Giovanni degli Eremiti 64 Convento della Magione 65 Palazzo Ajutamicristo 67 Palazzo Mirto 68 Soprintendenza Mare 81 Casina Cinese 82 Castello della Cuba 83 Museo Regionale Antonino Salinas 84 Necropoli Punica 85 Oratorio dei Bianchi 86 Palazzo Montalbo 87 Villino Florio 7 Chiostro -

Mortuary Variability in Early Iron Age Cretan Burials

MORTUARY VARIABILITY IN EARLY IRON AGE CRETAN BURIALS Melissa Suzanne Eaby A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Classics. Chapel Hill 2007 Approved by: Donald C. Haggis Carla M. Antonaccio Jodi Magness G. Kenneth Sams Nicola Terrenato UMI Number: 3262626 Copyright 2007 by Eaby, Melissa Suzanne All rights reserved. UMI Microform 3262626 Copyright 2007 by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest Information and Learning Company 300 North Zeeb Road P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, MI 48106-1346 © 2007 Melissa Suzanne Eaby ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT MELISSA SUZANNE EABY: Mortuary Variability in Early Iron Age Cretan Burials (Under the direction of Donald C. Haggis) The Early Iron Age (c. 1200-700 B.C.) on Crete is a period of transition, comprising the years after the final collapse of the palatial system in Late Minoan IIIB up to the development of the polis, or city-state, by or during the Archaic period. Over the course of this period, significant changes occurred in settlement patterns, settlement forms, ritual contexts, and most strikingly, in burial practices. Early Iron Age burial practices varied extensively throughout the island, not only from region to region, but also often at a single site; for example, at least 12 distinct tomb types existed on Crete during this time, and both inhumation and cremation were used, as well as single and multiple burial. -

Wine Tourism in Crete!

Wine tourism in Crete! Plan Days 7 Discover the particularity of the local varieties, visit important archaeological sites and get acquainted with the unique Cretan hospitality, on a magical journey across the island. By: Wondergreece Traveler PLAN SUMMARY Day 1 1. Chania International Airport “Ioannis Daskalogiannis” About region/Access & Useful info 2. Alcanea Boutique Hotel Accommodation 3. Venetian harbor of Chania Culture/Monuments & sights 4. The Archeological Museum of Chania Culture/Museums 5. Alcanea Boutique Hotel Accommodation Day 2 1. Alcanea Boutique Hotel Accommodation 2. The dome-shaped tomb in Maleme Culture/Archaelogical sites 3. Anoskeli Winery & Oil Mill Local Products & Gastronomy/Wineries 4. Tamam Food, Shops & Rentals/Food 5. Pasteleria de Dana Food, Shops & Rentals/Food 6. Alcanea Boutique Hotel Accommodation Day 3 1. Alcanea Boutique Hotel Accommodation 2. Ancient Aptera Culture/Archaelogical sites 3. Dourakis Winery Local Products & Gastronomy/Wineries 4. Rethymno About region/Main cities & villages 5. The archeological site of Eleftherna Culture/Archaelogical sites 6. Scalani Hills Boutari Winery & Residences Accommodation Day 4 1. Scalani Hills Boutari Winery & Residences Accommodation 2. Nikos Kazantzakis Museum Culture/Museums WonderGreece.gr - Bon Voyage 1 3. Heraklion About region/Main cities & villages 4. The Fortress “Rocca al Mare” (Koules) Culture/Castles 5. Scalani Hills Boutari Winery & Residences Accommodation Day 5 1. Scalani Hills Boutari Winery & Residences Accommodation 2. Knossos Palace Culture/Archaelogical sites 3. Elounda About region/Main cities & villages 4. Spinalonga Culture/Monuments & sights 5. Cressa Ghitonia Village Accommodation Day 6 1. Cressa Ghitonia Village Accommodation 2. Toplou Monastery Winery Local Products & Gastronomy/Wineries 3. Ancient Itanos Culture/Archaelogical sites 4. -

Etruscan News 19

Volume 19 Winter 2017 Vulci - A year of excavation New treasures from the Necropolis of Poggio Mengarelli by Carlo Casi InnovativeInnovative TechnologiesTechnologies The inheritance of power: reveal the inscription King’s sceptres and the on the Stele di Vicchio infant princes of Spoleto, by P. Gregory Warden by P. Gregory Warden Umbria The Stele di Vicchio is beginning to by Joachim Weidig and Nicola Bruni reveal its secrets. Now securely identi- fied as a sacred text, it is the third 700 BC: Spoleto was the center of longest after the Liber Linteus and the Top, the “Tomba della Truccatrice,” her cosmetics still in jars at left. an Umbrian kingdom, as suggested by Capua Tile, and the earliest of the three, Bottom, a warrior’s iron and bronze short spear with a coiled handle. the new finds from the Orientalizing securely dated to the end of the 6th cen- necropolis of Piazza d’Armi that was tury BCE. It is also the only one of the It all started in January 2016 when even the heavy stone cap of the chamber partially excavated between 2008 and three with a precise archaeological con- the guards of the park, during the usual cover. The robbers were probably dis- 2011 by the Soprintendenza text, since it was placed in the founda- inspections, noticed a new hole made by turbed during their work by the frequent Archeologia dell’Umbria. The finds tions of the late Archaic temple at the grave robbers the night before. nightly rounds of the armed park guards, were processed and analysed by a team sanctuary of Poggio Colla (Vicchio di Strangely the clandestine excavation but they did have time to violate two of German and Italian researchers that Mugello, Firenze). -

Th1rzne CEEK

HESPERIA 68.2, I999 "'ADYTO N ," "OPI STHO DOO S," AND THE INNER ROO/ OFr TH1rznECEEK/ T EMPLED For Lucy Shoe Meritt We know very little of what took place inside a Greek temple. Sacrifice, the focal act of communal religious observance,was enacted outside, on an open-air altar usually opposite the main, east, facade of the temple, while the interior contained objects dedicated to the deity, including a cult statue. In form most Greek temples had a single main interior room, or cella; some had an additional small room behind it, accessible only from the cella. Such a subdivision of interior space suggests that the inner chamber served a special function. This study is designed to ascertain why some temples had inner rooms and how these chambers were used, questions that shed light on the nature of the temple itself. Examination of termi- nology used for temple interiors and of archaeological remains of temples with inner rooms, together with literary and epigraphical references to activities that occurred in temples, indicates a larger economic role for many temples and less secret ritual than has been assumed.1 Nomenclature is a central issue here, as naming incorporates a set of 1. This article is dedicatedto Lucy Since the 19th century, the in- Shoe Meritt, with gratitude,for her assumptions and a specific interpretation. generosityin sharingher expertisein ner room has been called 'a'UTOV (adyton, "not to be entered"), a term and enthusiasmfor Greek architecture. known from ancient sources. The usage of "adyton" in literary and In the uncommonlylong develop- epigraphical testimonia led scholars to consider the inner room a locus of ment of this article,I have received cult ritual of a chthonian or oracular nature, mysterious rites conducted exceptionalassistance from Susan within the temple. -

DIMAURO ETTORE Luogo Di Nascita

CURRICULUM VITAE DATI ANAGRAFICI Cognome e nome: DIMAURO ETTORE Luogo di nascita: Data di nascita: Qualifica: DIRIGENTE DI TERZA FASCIA – ARCHITETTO Incarico attuale: DIRIGENTE RESPONSABILE UNITA’ OPERATIVA V – Tutela e Valorizzazione Beni Archeologici - (Incarico dal 20/09/2004 al 2010) Sede di lavoro: SOPRINTENDENZA BB.CC.AA. DI CALTANISSETTA dal 01 MARZO 1991 Casella di posta: Residenza: Telefono ufficio: Fax ufficio: Cod. Fiscale: Titolo di studio: Laurea in Architettura conseguita presso l’Università degli Studi di Palermo nel 1984 Sintesi esperienze professionali: 1984 - Si laurea presso la Facoltà di Architettura di Palermo. Nello stesso anno apre uno studio di progettazione architettonica a Caltanissetta e forma il gruppo “Itaca Architetti Associati”. 1986 - Partecipa al "Concorso di idee per la progettazione del Santuario della Madonna della Cava a Marsala" ottenendo una segnalazione. 1991– Assume il ruolo di Dirigente presso la Soprintendenza ai Beni Culturali ed Ambientali di Caltanissetta, dove svolge ininterrottamente il proprio ruolo nell’ambito del Servizio per i Beni Architettonici Paesistici, Naturali, Naturalistici ed Urbanistici fino al 2004. Dal 2004 è nominato Dirigente Responsabile dell’Unità Operativa V – “Tutela e valorizzazione dei Beni Archeologici”, coordinando altresì il personale di custodia dei Musei Archeologici di Caltanissetta e Marianopoli. 1 1991 – E’ invitato ad esporre i propri progetti di architettura, alla Biennale di Venezia, Padiglione Italia, in occasione della V Mostra Internazionale di Architettura. 1993 - Partecipa al "Concorso Nazionale Una via tre piazze a Gela" ottenendo una menzione speciale. 1993-1994 –E’ Consigliere dell’Ordine degli Architetti di Caltanissetta e delegato alla Commissione Cultura istituita presso la Consulta Regionale degli Architetti. 1995-1999 - E’ Docente di Paesaggistica e di Teoria del Restauro nonchè Coordinatore del Corso di Specializzazione post-diploma tenuto all’ I.T.G. -

876626.En Pe 472.505

Question for written answer E-008255/2011 to the Commission Rule 117 Sonia Alfano (ALDE) Subject: Erosion and disappearance of the beach at Desusino (Caltanissetta province, Italy), a Natura 2000 site The coastline at Marina di Butera (Caltanissetta province, Italy) consists of some 8.4 km, stretching from Manfria to Castello di Falconara. The area forms part of the EU's Natura 2000 network, under both the habitats directive (ITA050011 Torre Manfria) and the wild birds directive ( ITA050012 Torre Manfria, Biviere and Piana di Gela). Unfortunately, thanks to a series of human interventions and the short-termism of local and regional politics, recent decades have witnessed a steady deterioration in this coastline, and especially in the area around Desusino, where continual erosion is now reaching the point where parts of the coastline are disappearing altogether. Only in the last three years, 20 metres of beach have disappeared, as is clear from the photographic evidence attached to the geomorphological study of the Butera coastline carried out by the geology department at Catania University. The data concerned may be found on- line at: http://4.bp.blogspot.com/- cw67Dj469qQ/TfnsUHPot7I/AAAAAAAAAf0/NHfT5EQ5nPc/s1600/erosione+2008-2010.jpg). In the wake of protests from a spontaneously created citizens' committee, the Sicily region appeared to have committed itself to financing an initial extraordinary intervention with a view to rehabilitating this coastline, but subject to the municipality of Butera submitting a preliminary project for the operation by September 2010. Unfortunately, the municipality did not submit that project, possibly for lack of funds. The result is that, with the two authorities each seeking to pin responsibility on the other, nothing whatever has been done to protect this Natura 2000 site.