Überschrift 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Equality in the Colonies: Concepts of Equality in Sicily During the Eighth to Six Centuries BC Author(S): Matthew Fitzjohn Source: World Archaeology, Vol

Equality in the Colonies: Concepts of Equality in Sicily during the Eighth to Six Centuries BC Author(s): Matthew Fitzjohn Source: World Archaeology, Vol. 39, No. 2, The Archaeology of Equality (Jun., 2007), pp. 215- 228 Published by: Taylor & Francis, Ltd. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/40026654 . Accessed: 18/09/2011 07:36 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Taylor & Francis, Ltd. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to World Archaeology. http://www.jstor.org Equality in the colonies: concepts of equality in Sicily duringthe eighth to six centuries bc MatthewFitzjohn Abstract In thelate eighthand earlyseventh centuries BC, a seriesof Greeksettlements of significantsize and organizationwere established on the east coast of Sicily.Their spatial organizationand systemsof land tenureappear to have been establishedon the principleof equality.This standsin contrastto the widelyheld beliefthat relationsbetween Greeks and the indigenouspopulation were based predominantlyon inequality.The aim of this articleis to re-examinethe materialexpression of equalityin the Greek settlementsand to reflectupon the ways in whichour categoriesof colonizer and colonizedhave influencedthe way thatwe look forand understandthe social relationsbetween people. I argue that the evidence of hybridforms of existenceas expressedthrough material culturerepresent different forms of equalitythat were experienced across the island in the Archaic period. -

Flussi Visitatori 2009 Completodef

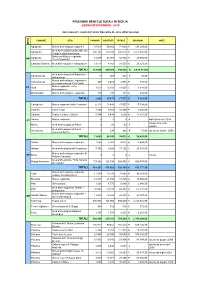

FRUIZIONE BENI CULTURALI IN SICILIA GENNAIO/DICEMBRE 2009 dati elaborati e curati dell' Unita' Operativa III - Area Affari Generali COMUNE SITO PAGANTI GRATUITI TOTALE INCASSO NOTE PROV. Agrigento Museo archeologico regionale 15.838 55.800 71.638 € 138.293,00 Area Archeologica della Valle dei Agrigento 308.745 233.930 542.675 € 2.477.647,00 Templi e della Kolimbetra. Biblioteca Museo regionale Agrigento 15.675 43.087 58.762 € 29.506,00 AG "Luigi Pirandello" Cattolica Eraclea Area archeologica e Antiquarium 13.410 8.163 21.573 € 25.127,00 TOTALI 353.668 340.980 694.648 € 2.670.573,00 Area archeologica di Sabucina e Caltanissetta 13 608 621 € 25,00 Antiquarium Museo archeologico regionale e Caltanissetta 427 2.474 2.901 € 784,00 area archeologica Gibil Gabib Museo regionale e aree CL Gela 1.513 12.154 13.667 € 4.141,50 archeologiche Marianopoli Museo archeologico regionale 140 243 383 € 232,00 TOTALI 2.093 15.479 17.572 € 5.182,50 Caltagirone Museo regionale della Ceramica 6.111 11.446 17.557 € 17.794,00 Catania Casa Verga 1.266 9.203 10.469 € 3.494,00 Catania Teatro romano e Odeon 4.244 3.414 7.658 € 11.522,00 CT Adrano Museo regionale 0 0 0 € - biglietteria non attiva chiuso solo visite Mineo Area archeologica di Palikè 0 93 93 € - guidate Area archeologica di Santa Acicastena 8 234 242 € 15,00 aperto da ottobre 2009 Venera al Pozzo TOTALI 11.629 24.390 36.019 € 32.825,00 Aidone Museo archeologico regionale 1.265 3.562 4.827 € 3.649,00 Aidone Area archeologica di Morgantina 7.300 9.826 17.126 € 21.241,00 Museo archeologico regionale di -

The Coinage of Akragas C

ACTA UNIVERSITATIS UPSALIENSIS Studia Numismatica Upsaliensia 6:1 STUDIA NUMISMATICA UPSALIENSIA 6:1 The Coinage of Akragas c. 510–406 BC Text and Plates ULLA WESTERMARK I STUDIA NUMISMATICA UPSALIENSIA Editors: Harald Nilsson, Hendrik Mäkeler and Ragnar Hedlund 1. Uppsala University Coin Cabinet. Anglo-Saxon and later British Coins. By Elsa Lindberger. 2006. 2. Münzkabinett der Universität Uppsala. Deutsche Münzen der Wikingerzeit sowie des hohen und späten Mittelalters. By Peter Berghaus and Hendrik Mäkeler. 2006. 3. Uppsala universitets myntkabinett. Svenska vikingatida och medeltida mynt präglade på fastlandet. By Jonas Rundberg and Kjell Holmberg. 2008. 4. Opus mixtum. Uppsatser kring Uppsala universitets myntkabinett. 2009. 5. ”…achieved nothing worthy of memory”. Coinage and authority in the Roman empire c. AD 260–295. By Ragnar Hedlund. 2008. 6:1–2. The Coinage of Akragas c. 510–406 BC. By Ulla Westermark. 2018 7. Musik på medaljer, mynt och jetonger i Nils Uno Fornanders samling. By Eva Wiséhn. 2015. 8. Erik Wallers samling av medicinhistoriska medaljer. By Harald Nilsson. 2013. © Ulla Westermark, 2018 Database right Uppsala University ISSN 1652-7232 ISBN 978-91-513-0269-0 urn:nbn:se:uu:diva-345876 (http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:uu:diva-345876) Typeset in Times New Roman by Elin Klingstedt and Magnus Wijk, Uppsala Printed in Sweden on acid-free paper by DanagårdLiTHO AB, Ödeshög 2018 Distributor: Uppsala University Library, Box 510, SE-751 20 Uppsala www.uu.se, [email protected] The publication of this volume has been assisted by generous grants from Uppsala University, Uppsala Sven Svenssons stiftelse för numismatik, Stockholm Gunnar Ekströms stiftelse för numismatisk forskning, Stockholm Faith and Fred Sandstrom, Haverford, PA, USA CONTENTS FOREWORDS ......................................................................................... -

Sakraler Raum – Sakrale Räume“, FS 2012 Agrigent A

Bibliographie Seminar „Sakraler Raum – Sakrale Räume“, FS 2012 Agrigent A. Bellia, Music and Rite. Musical Instruments in the Sanctuary of the Chthonic Divinities in Akragas (6th Century BC), in: R. Eichmann – E. Hickmann – L.-Ch. Koch (Hrsg.), Studien zur Musikarchäologie VII. Musikalische Wahrnehmung in Vergangenheit und Gegenwart. Ethnographische Analogien in der Musikarchäologie. Vorträge des 6. Symposiums der Internationalen Studiengruppe Musikarchäologie in Berlin, 9.-13. September 2008 (Rahden 2010) 3-8. P. Meli, Asklepieion di Agrigento: Restauro e ricostituzione del bosco sacro, in: E. De Miro – G. Sfameni Gasparro – V. Calì (Hrsg.), Il culto di Asclepio nell’area mediterranea. Atti del Convegno Internazionale, Agrigento 20-22 novembre 2005 (Rom 2009) 175- 177. C. Zoppi, La lavorazione del crepidoma e il problema della datazione del tempio di Asclepio di Agrigento, SicA 39, 2006, 47-54. G. Arnone, L’Asklepieion akragantino, Archivio storico siciliano 31, 2005, 251-256. V. Calì, I santuari ctoni di Agrigento e Siracusa, in: P. Minà (Hrsg.), Urbanistica e architettura nella Sicilia greca. Ausstellungskatalog Agrigent (Palermo 2005) 178-181. G. Fiorentini, Agrigento. La nuova area sacra sulle pendici dell’Acropoli, in: R. Gigli (Hrsg.), ΜΕΓΑΛΑΙ ΝΗΣΟΙ. Studi dedicati a Giovanni Rizza per il suo ottantesimo compleanno 2 (Palermo 2005) 147-165. G. Ortolani, La valle dei templi di Agrigento (Rom 2004). C. Zoppi, Le fasi costruttive del cosidetto santuario rupestre di San Biagio ad Agrigento: Alcune osservazioni, SicAnt 1, 2004, 41-79. E. De Miro, Agrigento II. I santuari extraurbani. L’Asklepieion (Rom 2003). J. de Waele, La standardizzazione dei blocchi nei templi „gemelli“ di Agrigento, in: G. Fiorentini – M. -

A Dynamic Analysis of Tourism Determinants in Sicily

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by NORA - Norwegian Open Research Archives A Dynamic Analysis of Tourism Determinants in Sicily Davide Provenzano Master Programme in System Dynamics Department of Geography University of Bergen Spring 2009 Acknowledgments I am grateful to the Statistical Office of the European Communities (EUROSTAT); the Italian National Institute of Statistics (ISTAT), the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO); the European Climate Assessment & Dataset (ECA&D 2009), the Statistical Office of the Chamber of Commerce, Industry, Craft Trade and Agriculture (CCIAA) of Palermo; the Italian Automobile Club (A.C.I), the Italian Ministry of the Environment, Territory and Sea (Ministero dell’Ambiente e della Tutela del Territorio e del Mare), the Institute for the Environmental Research and Conservation (ISPRA), the Regional Agency for the Environment Conservation (ARPA), the Region of Sicily and in particular to the Department of the Environment and Territory (Assessorato Territorio ed Ambiente – Dipartimento Territorio ed Ambiente - servizio 6), the Department of Arts and Education (Assessorato Beni Culturali, Ambientali e P.I. – Dipartimento Beni Culturali, Ambientali ed E.P.), the Department of Communication and Transportation (Assessorato del Turismo, delle Comunicazioni e dei Trasporti – Dipartimento dei Trasporti e delle Comunicazioni), the Department of Tourism, Sport and Culture (Assessorato del Turismo, delle Comunicazioni e dei Trasporti – Dipartimento Turismo, Sport e Spettacolo), for the high-quality statistical information service they provide through their web pages or upon request. I would like to thank my friends, Antonella (Nelly) Puglia in EUROSTAT and Antonino Genovesi in Assessorato Turismo ed Ambiente – Dipartimento Territorio ed Ambiente – servizio 6, for their direct contribution in my activity of data collecting. -

ANCIENT TERRACOTTAS from SOUTH ITALY and SICILY in the J

ANCIENT TERRACOTTAS FROM SOUTH ITALY AND SICILY in the j. paul getty museum The free, online edition of this catalogue, available at http://www.getty.edu/publications/terracottas, includes zoomable high-resolution photography and a select number of 360° rotations; the ability to filter the catalogue by location, typology, and date; and an interactive map drawn from the Ancient World Mapping Center and linked to the Getty’s Thesaurus of Geographic Names and Pleiades. Also available are free PDF, EPUB, and MOBI downloads of the book; CSV and JSON downloads of the object data from the catalogue and the accompanying Guide to the Collection; and JPG and PPT downloads of the main catalogue images. © 2016 J. Paul Getty Trust This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, CA 94042. First edition, 2016 Last updated, December 19, 2017 https://www.github.com/gettypubs/terracottas Published by the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles Getty Publications 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 500 Los Angeles, California 90049-1682 www.getty.edu/publications Ruth Evans Lane, Benedicte Gilman, and Marina Belozerskaya, Project Editors Robin H. Ray and Mary Christian, Copy Editors Antony Shugaar, Translator Elizabeth Chapin Kahn, Production Stephanie Grimes, Digital Researcher Eric Gardner, Designer & Developer Greg Albers, Project Manager Distributed in the United States and Canada by the University of Chicago Press Distributed outside the United States and Canada by Yale University Press, London Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: J. -

Scheda Progetto Beni Culturali

INQUADRAMENTO TERRITORIALE E SOCIO ECONOMICO L’intervento si snoda pressoché in tutta la Regione Sicilia interessando Novantacinque siti territorialmente riconducibili a due macro ambiti territoriali: urbano ed extraurbano. Tra i siti collocati in ambito extraurbano ritroviamo essenzialmente gli «antiquaria», connessi alle aree archeologiche, che, in alcuni casi, sono a loro volta costituiti da insiemi di edifici dalle caratteristiche architettoniche e morfologiche eterogenee. Per non appesantire l’esposizione degli interventi tali fattispecie sono state trattate nell’ambito del macro sito archeologico. Esemplificativo il caso del Parco archeologico di Selinunte, al numero trenta della proposta, che annovera oltre venti piccoli edifici dislocati «a random» nel territorio del Parco, trattati in maniera aggregata nel Progetto di FTE specifico del già citato sito 30 Parco archeologico di Selinunte. Individuazione dei siti oggetto di intervento indicati per provincia di appartenenza. Provincia di Palermo 26 siti Codice numerico proposta Denominazione sito 1 Albergo delle Povere 2 Biblioteca Centrale Palermo 3 Castello Zisa 4 Dipartimento BBCC Palermo 5 Palazzo Abatellis 6 Palazzo Riso 8 Castello Maredolce / Palazzo della Favara 14 Castello a mare 63 Chiostro di San Giovanni degli Eremiti 64 Convento della Magione 65 Palazzo Ajutamicristo 67 Palazzo Mirto 68 Soprintendenza Mare 81 Casina Cinese 82 Castello della Cuba 83 Museo Regionale Antonino Salinas 84 Necropoli Punica 85 Oratorio dei Bianchi 86 Palazzo Montalbo 87 Villino Florio 7 Chiostro -

NOTIZIARIO DI PREISTORIA E PROTOSTORIA - 2.II Sardegna E Sicilia

ISTITUTO ITALIANO DI PREISTORIA E PROTOSTORIA NOTIZIARIO DI PREISTORIA E PROTOSTORIA - 2.II Sardegna e Sicilia 2015 - 2.II- www.iipp.it - ISSN 2384-8758 NOTIZIARIO DI PREISTORIA E PROTOSTORIA - 2015, 2.II ISTITUTO ITALIANO DI PREISTORIA E PROTOSTORIA SCOPERTE E SCAVI PREISTORICI IN ITALIA - ANNO 2014 NEOLITICO ED ETÀ DEI METALLI RiccardoSARDEGNA Cicilloni 37 Serri (Sarcidano, Prov. di Cagliari) Anna Depalmas, Claudio Bulla, Giovanna Fundoni 40 Abini (Teti, Prov. di Nuoro) Notiziario di Preistoria e Protostoria -2015, 2.II Luigi Campagna Sardegna e Sicilia 43 Protonuraghi Pigalva e Sorighina (Tula, Prov. Sassari) SICILIA 46 OrazioLoc. Valcorrente Palio, Maria (Belpasso, Turco, Simona Prov. di Todaro Catania). La quarta campagna di scavo. Orazio Palio, Maria Turco 49 Strutture megalitiche nell’area etnea (Bronte, Prov. di Catania). Enrico Giannitrapani, Filippo Iannì Case Bastione (Villarosa, Prov. di Enna) Redazione: , 52 Comitato di lettura: Monica Miari Francesco Rubat Borel 56 FrancescaSan Vincenzo, Ferranti, Isola Marco di Stromboli Bettelli, Valentina(Lipari, Prov.Cannavò, di Messina)Andrea Di - Consiglio Direttivo dell’IIPP - Clarissa Belardelli, Renzoni,Campagna Sara 2014 T. Levi, Maria Clara Martinelli Maria Bernabò Brea, Massimo Cultraro, Raffaele de Marinis, Andrea De Pascale, Carlo Lugliè, Monica Miari, Fabio Negrino, Andrea Pessina, . FrancescoLayout: Rubat Borel Giovanni Di Stefano, Pietro Militello 63 Calaforno (Giarratana, Prov. di Ragusa) Indagini 2013-2014 Monica Miari Pietro Militello, Anna M. Sammito 66 Calicantone (Modica- Cava Ispica). Campagna di scavo 2014 Istituto Italiano di Preistoria e Protostoria, 2015 Via S. Egidio, 21 – 50122 Firenze www.iipp.it – e-mail: [email protected] In copertina: la Capanna 3 di San Vincenzo, Stromboli (ME). -

Iconography of the Gorgons on Temple Decoration in Sicily and Western Greece

ICONOGRAPHY OF THE GORGONS ON TEMPLE DECORATION IN SICILY AND WESTERN GREECE By Katrina Marie Heller Submitted to the Faculty of The Archaeological Studies Program Department of Sociology and Archaeology In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Science University of Wisconsin-La Crosse 2010 Copyright 2010 by Katrina Marie Heller All Rights Reserved ii ICONOGRAPHY OF THE GORGONS ON TEMPLE DECORATION IN SICILY AND WESTERN GREECE Katrina Marie Heller, B.S. University of Wisconsin - La Crosse, 2010 This paper provides a concise analysis of the Gorgon image as it has been featured on temples throughout the Greek world. The Gorgons, also known as Medusa and her two sisters, were common decorative motifs on temples beginning in the eighth century B.C. and reaching their peak of popularity in the sixth century B.C. Their image has been found to decorate various parts of the temple across Sicily, Southern Italy, Crete, and the Greek mainland. By analyzing the city in which the image was found, where on the temple the Gorgon was depicted, as well as stylistic variations, significant differences in these images were identified. While many of the Gorgon icons were used simply as decoration, others, such as those used as antefixes or in pediments may have been utilized as apotropaic devices to ward off evil. iii Acknowledgements I would first like to thank my family and friends for all of their encouragement throughout this project. A special thanks to my parents, Kathy and Gary Heller, who constantly support me in all I do. I need to thank Dr Jim Theler and Dr Christine Hippert for all of the assistance they have provided over the past year, not only for this project but also for their help and interest in my academic future. -

A Companion to the Classical Greek World

A COMPANION TO THE CLASSICAL GREEK WORLD Edited by Konrad H. Kinzl A COMPANION TO THE CLASSICAL GREEK WORLD BLACKWELL COMPANIONS TO THE ANCIENT WORLD This series provides sophisticated and authoritative overviews of periods of ancient history, genres of classical literature, and the most important themes in ancient culture. Each volume comprises between twenty-five and forty concise essays written by individual scholars within their area of specialization. The essays are written in a clear, provocative, and lively manner, designed for an international audience of scholars, students, and general readers. ANCIENT HISTORY Published A Companion to Greek Rhetoric Edited by Ian Worthington A Companion to Roman Rhetoric Edited by William J. Dominik and Jonathan Hall A Companion to Classical Tradition Edited by Craig Kallendorf A Companion to the Roman Empire Edited by David S. Potter A Companion to the Classical Greek World Edited by Konrad H. Kinzl A Companion to the Ancient Near East Edited by Daniel C. Snell A Companion to the Hellenistic World Edited by Andrew Erskine In preparation A Companion to the Archaic Greek World Edited by Kurt A. Raaflaub and Hans van Wees A Companion to the Roman Republic Edited by Nathan Rosenstein and Robert Morstein-Marx A Companion to the Roman Army Edited by Paul Erdkamp A Companion to Byzantium Edited by Elizabeth James A Companion to Late Antiquity Edited by Philip Rousseau LITERATURE AND CULTURE Published A Companion to Ancient Epic Edited by John Miles Foley A Companion to Greek Tragedy Edited by Justina Gregory A Companion to Latin Literature Edited by Stephen Harrison In Preparation A Companion to Classical Mythology Edited by Ken Dowden A Companion to Greek and Roman Historiography Edited by John Marincola A Companion to Greek Religion Edited by Daniel Ogden A Companion to Roman Religion Edited by Jo¨rg Ru¨pke A COMPANION TO THE CLASSICAL GREEK WORLD Edited by Konrad H. -

DIMAURO ETTORE Luogo Di Nascita

CURRICULUM VITAE DATI ANAGRAFICI Cognome e nome: DIMAURO ETTORE Luogo di nascita: Data di nascita: Qualifica: DIRIGENTE DI TERZA FASCIA – ARCHITETTO Incarico attuale: DIRIGENTE RESPONSABILE UNITA’ OPERATIVA V – Tutela e Valorizzazione Beni Archeologici - (Incarico dal 20/09/2004 al 2010) Sede di lavoro: SOPRINTENDENZA BB.CC.AA. DI CALTANISSETTA dal 01 MARZO 1991 Casella di posta: Residenza: Telefono ufficio: Fax ufficio: Cod. Fiscale: Titolo di studio: Laurea in Architettura conseguita presso l’Università degli Studi di Palermo nel 1984 Sintesi esperienze professionali: 1984 - Si laurea presso la Facoltà di Architettura di Palermo. Nello stesso anno apre uno studio di progettazione architettonica a Caltanissetta e forma il gruppo “Itaca Architetti Associati”. 1986 - Partecipa al "Concorso di idee per la progettazione del Santuario della Madonna della Cava a Marsala" ottenendo una segnalazione. 1991– Assume il ruolo di Dirigente presso la Soprintendenza ai Beni Culturali ed Ambientali di Caltanissetta, dove svolge ininterrottamente il proprio ruolo nell’ambito del Servizio per i Beni Architettonici Paesistici, Naturali, Naturalistici ed Urbanistici fino al 2004. Dal 2004 è nominato Dirigente Responsabile dell’Unità Operativa V – “Tutela e valorizzazione dei Beni Archeologici”, coordinando altresì il personale di custodia dei Musei Archeologici di Caltanissetta e Marianopoli. 1 1991 – E’ invitato ad esporre i propri progetti di architettura, alla Biennale di Venezia, Padiglione Italia, in occasione della V Mostra Internazionale di Architettura. 1993 - Partecipa al "Concorso Nazionale Una via tre piazze a Gela" ottenendo una menzione speciale. 1993-1994 –E’ Consigliere dell’Ordine degli Architetti di Caltanissetta e delegato alla Commissione Cultura istituita presso la Consulta Regionale degli Architetti. 1995-1999 - E’ Docente di Paesaggistica e di Teoria del Restauro nonchè Coordinatore del Corso di Specializzazione post-diploma tenuto all’ I.T.G. -

(12) Sicily Index

INDEXRUNNING HEAD VERSO PAGES 527 Explanatory or more detailed references (where there are many) are given in bold. Numbers in italics are picture references. Dates are given for all artists, architects and sculptors. A Agrippa 468 Acate 319 Aidone 280 Aci Castello 421 Alagona, Archbishop 344 Acireale 419 Alcamo 145, 519 Acitrezza 420, 517 Alcantara Gorge 465 Acquacalda 479 Alcara Li Fusi 488 Acquaviva Platani 245 Alcibiades 402 Acquedolci 488 Alexander II, Pope 268, 289 Acrae 371, 372 Alexis of Tarentum 509 Acitrezza 517 Alì 467 Acron, physician 193 Alì Terme 467 Adelaide, Queen 281, 290, 484, 487, 488 Alì, Luciano (fl. late 17C–early 18C) 345 Adrano 412 Alì, Salvatore (fl. late 18C) 312 Aeolian Islands 277, 472–483 Alia 87 Aeschylus 248, 338, 357, 396, 410 Alibrandi, Girolamo (1470–1524) 414, St Agatha 396, 397, tomb 406 415, 450, 475 Agathocles 10, 84, 90, 143, 165, 250, Alicudi 481 339, 445 Al-Idrisi 510 Agira 283 Acitrezza 517 Agrigento 9, 193–211, 247, 248, 250, Amato, Andrea (fl. 1720–35) 401, 405, 353, 515 426 Duomo 195 Amato, Giacomo (1643–1732) 15, 43, Garden of Kolymbetra 204 46, 50 Museo Archeologico 204, 207 Amato, Paolo (1634–1714) 44, 54, 106, Museo Civico 194 170 Sanctuary of Demeter 209 Ambrogio da Como (fl. 1471–73) 91 Sanctuary of the Chthonic Divinities Amico, Giovanni Biagio (1684–1754) 53, 203 128, 131, 137, 147, 148, 156, 226 Temple of Asclepios 209 Anapo Valley 374 Temple of Castor and Pollux 203 Andrault, Michel (b. 1926) 354 Temple of Concord 199, 200 Andrea da Salerno (also known as Andrea Temple of Hephaistos 209, 210 Sabatini; c.