Preserving African American Historic Places

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Connecticut Preservation News

Connecticut Preservation News January/February 2018 Volume XLI, No. 1 Activism, Achievement, Architecture Preserving and Celebrating African American Historic Places mong the 90,000 places listed on the National Register a collaboration by Booker T. Washington and Sears Roebuck A of Historic Places, less than ten percent are dedicated president Julius Rosenwald to construct schools for African to people of color, said Brent Leggs, Senior Field Officer for American children throughout the South—was a transforma- the National Trust for Historic Preservation, speaking at the tive moment. “Booker T. Washington’s vision for uplifting Dixwell Congregational United Church of Christ, in New the black community through education affected my life,” Haven, in November. The event was organized by the New said Mr. Leggs. continued on page 4 Haven Preservation Trust and the State Historic Preservation Office. “This is an inequity that we have to correct,” he urged. Mr. Leggs introduced his talk by tracing his own develop- ment as a preservationist, a story that included childhood In This Issue: _____________________________________________ experiences of unconscious bias and a random conversation Remembering Vincent Scully 6 that convinced him to pursue graduate studies in preserva- _____________________________________________ tion. Participation in a survey of Rosenwald Schools— _____________________________________________ New Listings on the National Register 7 Funding for Preservation 8 New Haven Preservation Trust _____________________________________________ -

Boston Museum and Exhibit Reviews the Public Historian, Vol

Boston Museum and Exhibit Reviews The Public Historian, Vol. 25, No. 2 (Spring 2003), pp. 80-87 Published by: University of California Press on behalf of the National Council on Public History Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/tph.2003.25.2.80 . Accessed: 23/02/2012 10:14 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. University of California Press and National Council on Public History are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Public Historian. http://www.jstor.org 80 n THE PUBLIC HISTORIAN Boston Museum and Exhibit Reviews The American public increasingly receives its history from images. Thus it is incumbent upon public historians to understand the strategies by which images and artifacts convey history in exhibits and to encourage a conver- sation about language and methodology among the diverse cultural work- ers who create, use, and review these productions. The purpose of The Public Historian’s exhibit review section is to discuss issues of historical exposition, presentation, and understanding through exhibits mounted in the United States and abroad. Our aim is to provide an ongoing assess- ment of the public’s interest in history while examining exhibits designed to influence or deepen their understanding. -

Annual Report of the Librarian of Congress

ANNUAL REPO R T O F THE LIBR ARIAN OF CONGRESS ANNUAL REPORT OF T HE L IBRARIAN OF CONGRESS For the Fiscal Year Ending September , Washington Library of Congress Independence Avenue, S.E. Washington, DC For the Library of Congress on the World Wide Web visit: <www.loc.gov>. The annual report is published through the Public Affairs Office, Office of the Librarian, Library of Congress, Washington, DC -, and the Publishing Office, Library Services, Library of Congress, Washington, DC -. Telephone () - (Public Affairs) or () - (Publishing). Managing Editor: Audrey Fischer Copyediting: Publications Professionals LLC Indexer: Victoria Agee, Agee Indexing Design and Composition: Anne Theilgard, Kachergis Book Design Production Manager: Gloria Baskerville-Holmes Assistant Production Manager: Clarke Allen Library of Congress Catalog Card Number - - Key title: Annual Report of the Librarian of Congress For sale by the U.S. Government Printing Office Superintendent of Documents, Mail Stop: SSOP Washington, DC - A Letter from the Librarian of Congress / vii Library of Congress Officers and Consultants / ix Organization Chart / x Library of Congress Committees / xiii Highlights of / Library of Congress Bicentennial / Bicentennial Chronology / Congressional Research Service / Copyright Office / Law Library of Congress / Library Services / National Digital Library Program / Office of the Librarian / A. Bicentennial / . Steering Committee / . Local Legacies / . Exhibitions / . Publications / . Symposia / . Concerts: I Hear America Singing / . Living Legends / . Commemorative Coins / . Commemorative Stamp: Second-Day Issue Sites / . Gifts to the Nation / . International Gifts to the Nation / v vi Contents B. Major Events at the Library / C. The Librarian’s Testimony / D. Advisory Bodies / E. Honors / F. Selected Acquisitions / G. Exhibitions / H. Online Collections and Exhibitions / I. -

Download PDF Success Story

SUCCESS STORY Restoration of African American Church Interprets Abolitionist Roots Boston, Massachusetts “It makes me extremely proud to know that people around the world look to Massachusetts as the anti-slavery hub for the THE STORY In 1805, Thomas Paul, an African American preacher from New Hampshire, with 20 of important gatherings his members, officially formed the First African Baptist Church, and land was purchased that took place inside this for a building in what was the heart of Boston’s 19th century free black community. Completed in 1806, the African Meeting House was the first African Baptist Church national treasure. On behalf north of the Mason-Dixon Line. It was constructed almost entirely with black labor of the Commonwealth, I using funds raised from both the white and black communities. congratulate the Museum of The Meeting House was the community’s spiritual center and became the cultural, African American History educational, and political hub for Boston’s black population. The African School had for clearly envisioning how classes there from 1808 until a school was built in 1835. William Lloyd Garrison founded the New England Anti-Slavery Society in the Meeting House in 1832, and the church this project could be properly provided a platform for famous abolitionists and activists, including Frederick Douglass. executed and applaud the In 1863, it served as the recruitment site for the famed 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry regiment, the first African American military unit to fight for the Union in entire restoration team for the Civil War. As the black community migrated from the West End to the South End returning the Meeting House and Roxbury, the property was sold to a Jewish congregation in 1898. -

2016 AAAM Conference Bookl

Historic Emancipation Park / Houston, TX Celebrating 23 years of designing African American Museum and Cultural Centers OPENED OPENING SOON STUDIES 1993 North Carolina State University 2016 Smithsonian Institution Pope House Museum Foundation Study African American Cultural Center National Museum of African American Raleigh, NC Raleigh, NC History and Culture* *The Freelon Group remains the Architect of Record The Cultural Heritage Museum Study 2001 Hayti Heritage Center Historic Kinston, NC 2016 St. Joseph’s Performance Hall Historic Emancipation Park Houston, TX The African American Museum in Philadelphia Durham, NC Feasibility Study 2004 UNC Chapel Hill Sonja Haynes Stone 2017 Mississippi Civil Rights Museum Philadelphia, PA Center for Black Culture & History Jackson, MS African American Cultural Complex Study Chapel Hill, NC 2018 Freedom Park Raleigh, NC 2005 Raleigh, NC Reginald F. Lewis Museum of Maryland African American Cultural Consortium African American History and Culture 2018 Motown Museum Program Analysis and Feasibility Study Baltimore, MD Detroit, MI Raleigh, NC 2005 Museum of the African Diaspora San Francisco, CA Lucy Craft Laney Museum of Black History Augusta, GA 2009 Harvey B. Gantt Center for National Center for Rhythm and Blues African-American Arts + Culture Charlotte, NC Philadelphia, PA 2010 International Civil Rights Center and Museum Greensboro, NC 2014 National Center for Civil and Human Rights Atlanta, GA TABLE OF CONTENTS Board of Directors ..............................................4 Historical Overview -

Preservation, Recreation and Sport About the Conference

Updated 3/7/19. Check preservationconferenceri.com for latest updates and sold out sessions. Preservation, Recreation and Sport THE 34th ANNUAL RHODE ISLAND STATEWIDE HISTORIC PRESERVATION CONFERENCE East Providence Saturday, April 6, 2019 About the Conference Play ball! Preservation, Recreation and Sport, Rhode Island’s 34th Annual Statewide Historic Preservation Conference, will take place on Saturday, April 6. Rhode Islanders and visitors to the Ocean State love to play in historic places. The state’s coastal resort towns have hosted generations of summer visitors seeking rest and relaxation. Our cities erected large-scale sports venues for professional teams—and their adoring fans. Every community built its school gyms, little league fields, and public recreation facilities. By balancing historic preservation with the demands of the 21st century, these sites continue to play an active role in our lives. East Providence is our home turf. Tours will visit explore facilities at Agawam Hunt and the Indoor Tennis Court, visit the Crescent Park Carousel, and cruise the coastline to Pomham Rocks Lighthouse and the steamship graveyard at Green Jacket Shoal. Sessions will explore playful programming, preservation projects, recreation planning, Civil Rights, roadside architecture, and more. The conference is a gathering for anyone interested in preservation, history, design, and community planning. Who attends? Stewards of historic sports and recreation facilities; club members and sports buffs; grassroots preservationists throughout Rhode Island and the region; professionals working in the field or allied fields (architects, planners, landscape architects, developers, curators, etc.); elected officials and municipal board members; advocates and activists; students and teachers; and you. Register online by March 22. -

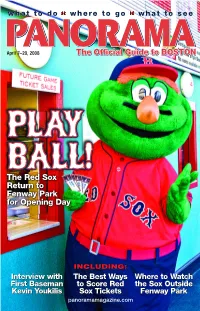

The Red Sox Return to Fenway Park for Opening Day

what to do • where to go • what to see April 7–20, 2008 Th eeOfOfficiaficialficial Guid eetoto BOSTON The Red Sox Return to Fenway Park for Opening Day INCLUDING:INCLUDING: Interview with The Best Ways Where to Watch First Baseman to Score Red the Sox Outside Kevin YoukilisYoukilis Sox TicketsTickets Fenway Park panoramamagazine.com BACK BY POPULAR DEMAND! OPENS JANUARY 31 ST FOR A LIMITED RUN! contents COVER STORY THE SPLENDID SPLINTER: A statue honoring Red Sox slugger Ted Williams stands outside Gate B at Fenway Park. 14 He’s On First Refer to story, page 14. PHOTO BY E THAN A conversation with Red Sox B. BACKER first baseman and fan favorite Kevin Youkilis PLUS: How to score Red Sox tickets, pre- and post-game hangouts and fun Sox quotes and trivia DEPARTMENTS "...take her to see 6 around the hub Menopause 6 NEWS & NOTES The Musical whe 10 DINING re hot flashes 11 NIGHTLIFE Men get s Love It tanding 12 ON STAGE !! Too! ovations!" 13 ON EXHIBIT - CBS Mornin g Show 19 the hub directory 20 CURRENT EVENTS 26 CLUBS & BARS 28 MUSEUMS & GALLERIES 32 SIGHTSEEING Discover what nearly 9 million fans in 35 EXCURSIONS 12 countries are laughing about! 37 MAPS 43 FREEDOM TRAIL on the cover: 45 SHOPPING Team mascot Wally the STUART STREET PLAYHOUSE • Boston 51 RESTAURANTS 200 Stuart Street at the Radisson Hotel Green Monster scores his opening day Red Sox 67 NEIGHBORHOODS tickets at the ticket ofofficefice FOR TICKETS CALL 800-447-7400 on Yawkey Way. 78 5 questions with… GREAT DISCOUNTS FOR GROUPS 15+ CALL 1-888-440-6662 ext. -

Constructing Community: Experiences of Identity, Economic Opportunity, and Institution Building at Boston’S African Meeting House

Constructing Community: Experiences of Identity, Economic Opportunity, and Institution Building at Boston’s African Meeting House David B. Landon & Teresa D. Bulger International Journal of Historical Archaeology ISSN 1092-7697 Int J Histor Archaeol DOI 10.1007/s10761-012-0212-z 1 23 Your article is protected by copyright and all rights are held exclusively by Springer Science +Business Media New York. This e-offprint is for personal use only and shall not be self- archived in electronic repositories. If you wish to self-archive your work, please use the accepted author’s version for posting to your own website or your institution’s repository. You may further deposit the accepted author’s version on a funder’s repository at a funder’s request, provided it is not made publicly available until 12 months after publication. 1 23 Author's personal copy Int J Histor Archaeol DOI 10.1007/s10761-012-0212-z Constructing Community: Experiences of Identity, Economic Opportunity, and Institution Building at Boston’s African Meeting House David B. Landon & Teresa D. Bulger # Springer Science+Business Media New York 2013 Abstract The African Meeting House in Boston became a center of the city’s free black community during the nineteenth century. Archaeological excavations at this site recovered material from the Meeting House backlot and a neighboring apartment building occupied by black tenants. These artifacts reveal strategies the community used to negotiate a place for themselves, create economic opportunities, and build community institutions. The Meeting House helped foster community success and became a powerful center for African American action on abolition, educational equality, and military integration. -

Providence RHODE ISLAND

2016 On Leadership Providence RHODE ISLAND 2016 OAH Annual Meeting Onsite Program RHODE ISLAND CONVENTION CENTER | APRIL 7–10 BEDFORD/ST. MARTIN’S For more information or to request your complimentary review copy now, stop by Booth #413 & 415 or visit us online at 2016 macmillanhighered.com/OAHAPRIL16 NEW Bedford Digital Collections The sources you want from the publisher you trust. Bedford Digital Collections offers a fresh and intuitive approach to teaching with primary sources. Flexible and affordable, this online repository of discovery-oriented projects can be easily customized to suit the way you teach. Take a tour at macmillanhighered.com/bdc Primary source projects Revolutionary Women’s Eighteenth-Century Reading World War I and the Control of Sexually Transmitted and Writing: Beyond “Remember the Ladies” Diseases Karin Wulf, College of William and Mary Kathi Kern, University of Kentucky The Antebellum Temperance Movement: Strategies World War I Posters and the Culture of American for Social Change Internationalism David Head, Spring Hill College Julia Irwin, University of South Florida The California Gold Rush: A Trans-Pacific Phenomenon War Stories: Black Soldiers and the Long Civil Rights David Igler, University of California, Irvine Movement Maggi Morehouse, Coastal Carolina University Bleeding Kansas: A Small Civil War Nicole Etcheson, Ball State University The Social Impact of World War II Kenneth Grubb, Wharton County Junior College What Caused the Civil War? Jennifer Weber, University of Kansas, Lawrence The Juvenile Delinquency/Comic -

Download Our Rental Brochure

FOR ANY OCCASION MUSEUM OF AFRICAN AMERICAN HISTORY Mu s e u m of The Museum of African American History invites Nestled on Boston’s Beacon Hill and at Nantucket’s Five individuals and organizations to enjoy the facilities and Corners are some of the nation’s most important resources in both Boston and Nantucket. Our spaces National Historic Landmarks. The Museum’s two African American offer the opportunity to make an event an enriching and campuses feature the earliest churches and schools still historical experience. We provide rentals for (but not standing in America that were built by and for black limited to): communities. Each is beautifully restored and worthy of His t o r y • Breakfast/Dinners any journey. Our historic sites, talks, tours, videos, collections, and programs are rooted in the past and RENTALS • Ceremonies connected to the present. • Concerts From the American Revolution to the Abolitionist and • Conferences Niagara Movements, experience powerful American • Holiday Parties stories through a new lens. Come to the Museum,where • Meetings Frederick Douglass and pioneering activists, entrepreneurs, journalists, educators, artists, and authors • Reunions organized campaigns that changed the nation. • Weddings • Workshops BOSTON African Meeting House (b. 1806) Abiel Smith School (b. 1835) 46 Joy Street, Beacon Hill THERE IS ALWAYS A STORY TO TELL MAAH.ORG • 617.725.0022 X22 OR X330/WEEKENDS Photo: Julia Sutton Smith, Hamilton Sutton Smith Collection, MAAH Collection, Smith Sutton Hamilton Smith, Sutton Julia Photo: A seamstress by trade from Massachusetts, Nancy Gardner had ambitions to improve her status in life and travel the world. She met Nero Prince who was a Grand Master of the Prince Hall Masonic Lodge and a guard for NANTUCKET African Meeting House (c.1820) the Czar of Russia. -

6Xsuhph &Rxuw Ri Wkh 8Qlwhg 6Wdwhv

1R ,17+( 6XSUHPH&RXUWRIWKH8QLWHG6WDWHV ²²²²²² 0255,6&2817<%2$5'2)&+26(1)5((+2/'(567+( 0255,6&2817<35(6(59$7,2175867)81'5(9,(: %2$5'-26(3+$.29$/&,.-5,1+,62)),&,$/ &$3$&,7<$60255,6&2817<75($685(5 3HWLWLRQHUV Y )5(('20)5205(/,*,21)281'$7,21$1' '$9,'67(.(7(( 5HVSRQGHQWV ²²²²²² 213(7,7,21)25:5,72)&(57,25$5,727+( 6835(0(&28572)7+(67$7(2)1(:-(56(< BBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBB %5,()2)$0,&86&85,$( 1$7,21$/75867)25+,6725,&35(6(59$7,21 ,168332572)3(7,7,21(56 BBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBB 7+$''(86+(8(5 (/,=$%(7+60(55,77 &RXQVHORI5HFRUG 1$7,21$/75867)25 $1'5(:/21'21 +,6725,&35(6(59$7,21 5$&+(/+87&+,1621 9,5*,1,$$9(1: )2/(<+2$*//3 68,7( 6HDSRUW%RXOHYDUG :$6+,1*721'& %RVWRQ0$ HPHUULWW#VDYLQJSODFHVRUJ WKHXHU#IROH\KRDJFRP 2FWREHU i TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ..................................... iii INTERESTS OF AMICUS CURIAE ......................... 1 SUMMARY OF THE ARGUMENT ........................... 2 ARGUMENT .............................................................. 5 I. PRESERVING HISTORIC RELIGIOUS STRUCTURES IS AN ISSUE OF NATIONAL IMPORTANCE ........................... 6 A. Protecting Historical and Architectural Heritage—both Secular and Religious—is a Legitimate Government Interest for Cultural, Aesthetic, and Economic Reasons ............................................................ 6 B. Governments Have a Legitimate Interest in Promoting the Historical, Architectural, and Cultural Heritage of Religious Structures ...................................................... 10 C. Federal, State, and Local Governments Regularly Fund the Preservation of Historic Religious Structures to Advance Secular Public Benefits ................................. 16 II. STATE COURTS ARE SPLIT ON WHETHER HISTORIC PRESERVATION GRANTS ARE A PUBLIC BENEFIT WITHIN THE SCOPE OF TRINITY LUTHERAN ................................................. -

Envisioning Villa Lewaro's Future

Envisioning VILLA LEWARO’S Future By Brent Leggs “I am a woman who came from the cotton fields of the South. From there I was promoted to the washtub. From there I was promoted to the kitchen cook. And from there I promoted myself into the business of manufacturing hair goods and preparations.” Madam CJ Walker 1912 National Negro Business League Convention Envisioning VILLA LEWARO’S Future NatioNal trust For Table of ConTenTs Historic PreservatioN stephanie K. meeKs president DaviD J. Brown . executive vice president Executive Summary 2 and Chief preservation officer taBitha almquist . Chief of staff Introduction and Background 3 roBert Bull Chief Development officer Historical Significance .......................................3 paul eDmonDson Chief legal officer Architectural Significance ....................................4 and General Counsel miChael l. forster Ownership History ..........................................4 Chief financial and administrative officer .............. amy maniatis Initial Assessment of Development Considerations 6 Chief marketing officer Envisioning Possible Reuse Scenarios . 8 A special acknowledgement to National Scenario 1: Health & Wellness Spa and Salon ..................9 Trust staff that worked on the report or contributed to the Villa Lewaro Scenario 2: Center for Innovation in Technology ............. 11 National Treasure campaign: David Brown, Paul Edmondson, Robert Bull, Scenario 3: Corporate Venue and Events Management ........ 13 John Hildreth, Dennis Hockman, Germonique Ulmer, Andrew Simpson,