Boston Museum and Exhibit Reviews the Public Historian, Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Samuel Adams

Monumental Milestones Milestones Monumental The Life and of Times samuel adams samuel adams Karen Bush Gibson The Life and Times of samuel Movement Rights Civil The adams Karen Bush Gibson As America’s first politician, Samuel Adams dedicated his life to improving the lives of the colonists. At a young age, he began talking and listening to people to find out what issues mattered the most. Adams proposed new ideas, first in his own newspaper, then in other newspapers throughout the colonies. When Britain began taxing the colonies, Adams encouraged boy- cotting and peaceful protests. He was an organizer of the Boston Tea Party, one of the main events leading up to the American Revolution. The British seemed intent on imprisoning Adams to keep him from speaking out, but he refused to stop. He was one of the first people to publicly declare that the colonies should be independent, and he worked tirelessly to see that they gained that independence. According to Thomas Jefferson, Samuel Adams was the Father of the Revolution. ISBN 1-58415-440-3 90000 9 PUBLISHERS 781584 154402 samueladamscover.indd 1 5/3/06 12:51:01 PM Copyright © 2007 by Mitchell Lane Publishers, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced without written permission from the publisher. Printed and bound in the United States of America. Printing 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Gibson, Karen Bush. The life and times of Samuel Adams/Karen Bush Gibson. p. cm. — (Profiles in American history) Includes bibliographical references and index. -

16 043539 Bindex.Qxp 10/10/06 8:49 AM Page 176

16_043539 bindex.qxp 10/10/06 8:49 AM Page 176 176 B Boston Public Library, 29–30 Babysitters, 165–166 Boston Public Market, 87 Index Back Bay sights and attrac- Boston Symphony Index See also Accommoda- tions, 68–72 Orchestra, 127 tions and Restaurant Bank of America Pavilion, Boston Tea Party, 43–44 Boston Tea Party Reenact- indexes, below. 126, 130 The Bar at the Ritz-Carlton, ment, 161–162 114, 118 Brattle, William, House A Barbara Krakow Gallery, (Cambridge), 62 Abiel Smith School, 49 78–79 Brattle Book Shop, 80 Abodeon, 85 Barnes & Noble, 79–80 Brattle Street (Cambridge), Access America, 167 Barneys New York, 83 62 Accommodations, 134–146. Bars, 118–119 Brattle Theatre (Cambridge), See also Accommodations best, 114 126, 129 Index gay and lesbian, 120 Bridge (Public Garden), 92 best bets, 134 sports, 122 The Bristol, 121 toll-free numbers and Bartholdi, Frédéric Brookline Booksmith, 80 websites, 175 Auguste, 70 Brooks Brothers, 83 Acorn Street, 49 Beacon Hill, 4 Bulfinch, Charles, 7, 9, 40, African Americans, 7 sights and attractions, 47, 52, 63, 67, 173 Black Nativity, 162 46–49 Bunker Hill Monument, 59 Museum of Afro-Ameri- Berklee Performance Center, Burleigh House (Cambridge), can History, 49 130 62 African Meeting House, 49 Berk’s Shoes (Cambridge), Burrage Mansion, 71 Agganis Arena, 130 83 Bus travel, 164, 165 Air travel, 163 Big Dig, 174 airline numbers and Black Ink, 85 C websites, 174–175 Black Nativity, 162 Calliope (Cambridge), 81 Alcott, Louisa May, 48, 149 The Black Rose, 122 Cambridge Common, 61 Alpha Gallery, 78 Blackstone -

Funding for Cultural Organizations in Boston and Nine Other Metropolitan Areas

UNDERSTANDING BOSTON Funding for Cultural Organizations in Boston and Nine Other Metropolitan Areas The Boston Foundation Publication Credits Author Susan Nelson, Principal, TDC Additional Research Anne Freeh Engel, TDC Karen Urosevich, TDC Project Coordinator and Editor Ann McQueen, Program Officer, Boston Foundation Editorial Consulting Angel Bermudez, Co-director of Program, Boston Foundation Terry Lane, Co-director of Program, Boston Foundation Design Kate Canfield, Canfield Design Cover Photo: Richard Howard The Boston Lyric Opera’s September 2002 presentation of Bizet’s Carmen attracted 140,000 people to two free performances on the Boston Common. © 2003 by The Boston Foundation. All rights reserved. Contents Preface . 4 Executive Summary. 5 Introduction . 11 CHAPTER ONE What are the Characteristics of Each Cultural Market?. 14 CHAPTER TWO How are Financial Resources Distributed Across the Sector?. 22 Cultural nonprofit institutions with annual budgets greater than $20 million . 24 Cultural organizations with annual budgets between $5 and $20 million . 26 Cultural nonprofit organizations with annual budgets between $1.5 and $5 million. 29 Organizations with budgets between $500,000 and $1.5 million . 32 Organizations with budgets under $500,000. 35 CHAPTER THREE What Types of Contributed Resources are Available? . 38 Government Funding. 39 Foundation Funding. 43 Corporate Funding. 46 Public Funding Strategies in Large Markets. 48 Public Funding Strategies in Small Markets. 49 Individual Giving . 53 CHAPTER FOUR What are the Implications of These Findings? . 54 End Paper . 56 APPENDIX ONE Data Sources Demographic Statistics. i Arts Nonprofit Organizations . ii State Arts Funding. ii Foundation Giving. ii Corporations . iii Local Arts Agencies . iii Literature. iii APPENDIX TWO Local Arts Agencies Boston . -

Sons of Liberty Patriots Or Terrorists

The Sons of Liberty : Patriots? OR Common ? Core Terrorists focused! http://www.teacherspayteachers.com/Store/Mr-Educator-A-Social-Studies-Professional Instructions: 1.) This activity can be implemented in a variety of ways. I have done this as a class debate and it works very, very well. However, I mostly complete this activity as three separate nightly homework assignments, or as three in-class assignments, followed by an in-class Socratic Seminar. The only reason I do this is because I will do the Patriots v. Loyalists: A Common Core Class Debate (located here: http://www.teacherspayteachers.com/ Product/Patriots-vs-Loyalists-A-Common-Core-Class-Debate-874989) and I don’t want to do two debates back-to-back. 2.) Students should already be familiar with the Sons of Liberty. If they aren’t, you may need to establish the background knowledge of what this group is and all about. 3.) I will discuss the questions as a class that are on the first page of the “Day 1” reading. Have classes discuss what makes someone a patriot and a terrorist. Talk about how they define these words? Can one be one without being the other? How? Talk about what both sides are after. What are the goals of terrorists? Why are they doing it? It is also helpful to bring in some outside quotes of notorious terrorists, such as Bin Laden, to show that they are too fighting for what they believe to be a just, noble cause. 4.) For homework - or as an in-class activity - assign the Day 1 reading. -

Metropolitan Boston Downtown Boston

WELCOME TO MASSACHUSETTS! CONTACT INFORMATION REGIONAL TOURISM COUNCILS STATE ROAD LAWS NONRESIDENT PRIVILEGES Massachusetts grants the same privileges EMERGENCY ASSISTANCE Fire, Police, Ambulance: 911 16 to nonresidents as to Massachusetts residents. On behalf of the Commonwealth, MBTA PUBLIC TRANSPORTATION 2 welcome to Massachusetts. In our MASSACHUSETTS DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION 10 SPEED LAW Observe posted speed limits. The runs daily service on buses, trains, trolleys and ferries 14 3 great state, you can enjoy the rolling Official Transportation Map 15 HAZARDOUS CARGO All hazardous cargo (HC) and cargo tankers General Information throughout Boston and surrounding towns. Stations can be identified 13 hills of the west and in under three by a black on a white, circular sign. Pay your fare with a 9 1 are prohibited from the Boston Tunnels. hours travel east to visit our pristine MassDOT Headquarters 857-368-4636 11 reusable, rechargeable CharlieCard (plastic) or CharlieTicket 12 DRUNK DRIVING LAWS Massachusetts enforces these laws rigorously. beaches. You will find a state full (toll free) 877-623-6846 (paper) that can be purchased at over 500 fare-vending machines 1. Greater Boston 9. MetroWest 4 MOBILE ELECTRONIC DEVICE LAWS Operators cannot use any of history and rich in diversity that (TTY) 857-368-0655 located at all subway stations and Logan airport terminals. At street- 2. North of Boston 10. Johnny Appleseed Trail 5 3. Greater Merrimack Valley 11. Central Massachusetts mobile electronic device to write, send, or read an electronic opens its doors to millions of visitors www.mass.gov/massdot level stations and local bus stops you pay on board. -

Hclassifi Cation

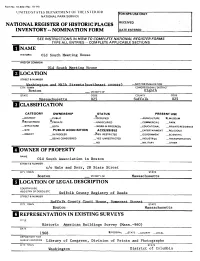

Form No 10-300 (Rev 10-74) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR FOR NPS USE GNtY NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES RECEIVE!} INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM DATE ENTERED SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS ____________TYPE ALL ENTRIES - COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS______ | NAME HISTORIC old South Meeting House AND/OR COMMON Old South Meeting House Q LOCATION STREETS NUMBER Washington and Milk Streets ("northeast corner) _ NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Boston _ VICINITY OF Eighth STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Massachusetts 025 Suffolk 025 HCLASSIFI CATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _DISTRICT _PUBLIC —OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE X-MUSEUM ^BUILDING(S) ^PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE _BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT —IN PROCESS -2VES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED —YES: UNRESTRICTED — INDUSTRIAL _ TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY —OTHER OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Old South Association in Boston STREETS NUMBER c/o Hale and Dorr, 28 State Street CITY. TOWN STATE Boston VICINITY OF Massachusetts LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS,ETC Suffolk County Registry of Deeds STREETS NUMBER Suffolk County Court House Somprspt Strppt CITY, TOWN STATE Boston Massachusetts REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS Historic American Buildings Survey (Mass.-960) DATE 1968 X-FEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Library of Congress, Division of Prints and Photographs CITY, TOWN STATE W&shington District of Columbia DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE ^EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED _UNALTERED ^.ORIGINAL SITE _GOOD _RUINS _XALTERED _MOVED DATE_____ _FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE Old South Meeting House, located at the northeast corner of Washington and Milk Streets in downtown Boston, was built as the second home of the Third Church in Boston, gathered in 1669. -

Freedom Trail N W E S

Welcome to Boston’s Freedom Trail N W E S Each number on the map is associated with a stop along the Freedom Trail. Read the summary with each number for a brief history of the landmark. 15 Bunker Hill Charlestown Cambridge 16 Musuem of Science Leonard P Zakim Bunker Hill Bridge Boston Harbor Charlestown Bridge Hatch Shell 14 TD Banknorth Garden/North Station 13 North End 12 Government Center Beacon Hill City Hall Cheers 2 4 5 11 3 6 Frog Pond 7 10 Rowes Wharf 9 1 Fanueil Hall 8 New England Downtown Crossing Aquarium 1. BOSTON COMMON - bound by Tremont, Beacon, Charles and Boylston Streets Initially used for grazing cattle, today the Common is a public park used for recreation, relaxing and public events. 2. STATE HOUSE - Corner of Beacon and Park Streets Adjacent to Boston Common, the Massachusetts State House is the seat of state government. Built between 1795 and 1798, the dome was originally constructed of wood shingles, and later replaced with a copper coating. Today, the dome gleams in the sun, thanks to a covering of 23-karat gold leaf. 3. PARK STREET CHURCH - One Park Street, Boston MA 02108 church has been active in many social issues of the day, including anti-slavery and, more recently, gay marriage. 4. GRANARY BURIAL GROUND - Park Street, next to Park Street Church Paul Revere, John Hancock, Samuel Adams, and the victims of the Boston Massacre. 5. KINGS CHAPEL - 58 Tremont St., Boston MA, corner of Tremont and School Streets ground is the oldest in Boston, and includes the tomb of John Winthrop, the first governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. -

Annual Report of the Librarian of Congress

ANNUAL REPO R T O F THE LIBR ARIAN OF CONGRESS ANNUAL REPORT OF T HE L IBRARIAN OF CONGRESS For the Fiscal Year Ending September , Washington Library of Congress Independence Avenue, S.E. Washington, DC For the Library of Congress on the World Wide Web visit: <www.loc.gov>. The annual report is published through the Public Affairs Office, Office of the Librarian, Library of Congress, Washington, DC -, and the Publishing Office, Library Services, Library of Congress, Washington, DC -. Telephone () - (Public Affairs) or () - (Publishing). Managing Editor: Audrey Fischer Copyediting: Publications Professionals LLC Indexer: Victoria Agee, Agee Indexing Design and Composition: Anne Theilgard, Kachergis Book Design Production Manager: Gloria Baskerville-Holmes Assistant Production Manager: Clarke Allen Library of Congress Catalog Card Number - - Key title: Annual Report of the Librarian of Congress For sale by the U.S. Government Printing Office Superintendent of Documents, Mail Stop: SSOP Washington, DC - A Letter from the Librarian of Congress / vii Library of Congress Officers and Consultants / ix Organization Chart / x Library of Congress Committees / xiii Highlights of / Library of Congress Bicentennial / Bicentennial Chronology / Congressional Research Service / Copyright Office / Law Library of Congress / Library Services / National Digital Library Program / Office of the Librarian / A. Bicentennial / . Steering Committee / . Local Legacies / . Exhibitions / . Publications / . Symposia / . Concerts: I Hear America Singing / . Living Legends / . Commemorative Coins / . Commemorative Stamp: Second-Day Issue Sites / . Gifts to the Nation / . International Gifts to the Nation / v vi Contents B. Major Events at the Library / C. The Librarian’s Testimony / D. Advisory Bodies / E. Honors / F. Selected Acquisitions / G. Exhibitions / H. Online Collections and Exhibitions / I. -

Download PDF Success Story

SUCCESS STORY Restoration of African American Church Interprets Abolitionist Roots Boston, Massachusetts “It makes me extremely proud to know that people around the world look to Massachusetts as the anti-slavery hub for the THE STORY In 1805, Thomas Paul, an African American preacher from New Hampshire, with 20 of important gatherings his members, officially formed the First African Baptist Church, and land was purchased that took place inside this for a building in what was the heart of Boston’s 19th century free black community. Completed in 1806, the African Meeting House was the first African Baptist Church national treasure. On behalf north of the Mason-Dixon Line. It was constructed almost entirely with black labor of the Commonwealth, I using funds raised from both the white and black communities. congratulate the Museum of The Meeting House was the community’s spiritual center and became the cultural, African American History educational, and political hub for Boston’s black population. The African School had for clearly envisioning how classes there from 1808 until a school was built in 1835. William Lloyd Garrison founded the New England Anti-Slavery Society in the Meeting House in 1832, and the church this project could be properly provided a platform for famous abolitionists and activists, including Frederick Douglass. executed and applaud the In 1863, it served as the recruitment site for the famed 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry regiment, the first African American military unit to fight for the Union in entire restoration team for the Civil War. As the black community migrated from the West End to the South End returning the Meeting House and Roxbury, the property was sold to a Jewish congregation in 1898. -

BOSTON CITY GUIDE @Comatbu CONTENTS

Tips From Boston University’s College of Communication BOSTON CITY GUIDE @COMatBU www.facebook.com/COMatBU CONTENTS GETTING TO KNOW BOSTON 1 MUSEUMS 12 Walking Franklin Park Zoo Public Transportation: The T Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum Bike Rental The JFK Library and Museum Trolley Tours Museum of Afro-American History Print & Online Resources Museum of Fine Arts Museum of Science The New England Aquarium MOVIE THEATERS 6 SHOPPING 16 LOCAL RADIO STATIONS 7 Cambridgeside Galleria Charles Street Copley Place ATTRACTIONS 8 Downtown Crossing Boston Common Faneuil Hall Boston Public Garden and the Swan Newbury Street Boats Prudential Center Boston Public Library Charlestown Navy Yard Copley Square DINING 18 Esplanade and Hatch Shell Back Bay Faneuil Hall Marketplace North End Fenway Park Quincy Market Freedom Trail Around Campus Harvard Square GETTING TO KNOW BOSTON WALKING BIKE RENTAL Boston enjoys the reputation of being among the most walkable Boston is a bicycle-friendly city with a dense and richly of major U.S. cities, and has thus earned the nickname “America’s interconnected street network that enables cyclists to make most Walking City.” In good weather, it’s an easy walk from Boston trips on relatively lightly-traveled streets and paths. Riding is the University’s campus to the Back Bay, Beacon Hill, Public Garden/ perfect way to explore the city, and there are numerous bike paths Boston Common, downtown Boston and even Cambridge. and trails, including the Esplanade along the Charles River. PUBLIC TRANSPORTATION: THE T Urban AdvenTours If you want to venture out a little farther or get somewhere a Boston-based bike company that offers bicycle tours seven days little faster, most of the city’s popular attractions are within easy a week at 10:00 a.m., 2:00 p.m., and 6:00 p.m. -

Unit 5 - the American Revolution

Unit 5 - The American Revolution Focus Questions 1. How did British colonial policies change after the Seven Years’ War, and how did American colonists react to those changes? 2. What major factors and events contributed to the colonial decision to declare independence from Great Britain, and how did the Declaration of Independence justify that decision? 3. Was the War for Independence also a “civil war” in the American colonies? 4. How did the American Revolution affect the lives and social roles for women and people of color? Did the move to colonial independence usher in a “social revolution” for America? Key Terms Royal Proclamation of 1763 Lexington and Concord Stamp Act Thomas Paine’s Common Sense Sons and Daughters of Liberty Battle of Saratoga Boston Massacre Charles Cornwallis Coercive Acts Articles of Confederation 73 74 Unit 5 – The American Revolution Introduction In the 1760s, Benjamin Rush, a native of Philadelphia, recounted a visit to Parliament. Upon seeing the king’s throne in the House of Lords, Rush said he “felt as if he walked on sacred ground” with “emotions that I cannot describe.”1 Throughout the eighteenth century, colonists had developed significant emotional ties to both the British monarchy and the British constitution. North American colonists had just helped to win a world war and most, like Rush, had never felt prouder to be British. And yet, in a little over a decade, those same colonists would declare their independence and break away from the British Empire. Seen from 1763, nothing would have seemed as improbable as the American Revolution. -

The Red Sox Return to Fenway Park for Opening Day

what to do • where to go • what to see April 7–20, 2008 Th eeOfOfficiaficialficial Guid eetoto BOSTON The Red Sox Return to Fenway Park for Opening Day INCLUDING:INCLUDING: Interview with The Best Ways Where to Watch First Baseman to Score Red the Sox Outside Kevin YoukilisYoukilis Sox TicketsTickets Fenway Park panoramamagazine.com BACK BY POPULAR DEMAND! OPENS JANUARY 31 ST FOR A LIMITED RUN! contents COVER STORY THE SPLENDID SPLINTER: A statue honoring Red Sox slugger Ted Williams stands outside Gate B at Fenway Park. 14 He’s On First Refer to story, page 14. PHOTO BY E THAN A conversation with Red Sox B. BACKER first baseman and fan favorite Kevin Youkilis PLUS: How to score Red Sox tickets, pre- and post-game hangouts and fun Sox quotes and trivia DEPARTMENTS "...take her to see 6 around the hub Menopause 6 NEWS & NOTES The Musical whe 10 DINING re hot flashes 11 NIGHTLIFE Men get s Love It tanding 12 ON STAGE !! Too! ovations!" 13 ON EXHIBIT - CBS Mornin g Show 19 the hub directory 20 CURRENT EVENTS 26 CLUBS & BARS 28 MUSEUMS & GALLERIES 32 SIGHTSEEING Discover what nearly 9 million fans in 35 EXCURSIONS 12 countries are laughing about! 37 MAPS 43 FREEDOM TRAIL on the cover: 45 SHOPPING Team mascot Wally the STUART STREET PLAYHOUSE • Boston 51 RESTAURANTS 200 Stuart Street at the Radisson Hotel Green Monster scores his opening day Red Sox 67 NEIGHBORHOODS tickets at the ticket ofofficefice FOR TICKETS CALL 800-447-7400 on Yawkey Way. 78 5 questions with… GREAT DISCOUNTS FOR GROUPS 15+ CALL 1-888-440-6662 ext.