Samuel Adams

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Utopian Promise

Unit 3 UTOPIAN PROMISE Puritan and Quaker Utopian Visions 1620–1750 Authors and Works spiritual decline while at the same time reaffirming the community’s identity and promise? Featured in the Video: I How did the Puritans use typology to under- John Winthrop, “A Model of Christian Charity” (ser- stand and justify their experiences in the world? mon) and The Journal of John Winthrop (journal) I How did the image of America as a “vast and Mary Rowlandson, A Narrative of the Captivity and unpeopled country” shape European immigrants’ Restoration of Mrs. Mary Rowlandson (captivity attitudes and ideals? How did they deal with the fact narrative) that millions of Native Americans already inhabited William Penn, “Letter to the Lenni Lenapi Chiefs” the land that they had come over to claim? (letter) I How did the Puritans’ sense that they were liv- ing in the “end time” impact their culture? Why is Discussed in This Unit: apocalyptic imagery so prevalent in Puritan iconog- William Bradford, Of Plymouth Plantation (history) raphy and literature? Thomas Morton, New English Canaan (satire) I What is plain style? What values and beliefs Anne Bradstreet, poems influenced the development of this mode of expres- Edward Taylor, poems sion? Sarah Kemble Knight, The Private Journal of a I Why has the jeremiad remained a central com- Journey from Boston to New York (travel narra- ponent of the rhetoric of American public life? tive) I How do Puritan and Quaker texts work to form John Woolman, The Journal of John Woolman (jour- enduring myths about America’s -

Boston Museum and Exhibit Reviews the Public Historian, Vol

Boston Museum and Exhibit Reviews The Public Historian, Vol. 25, No. 2 (Spring 2003), pp. 80-87 Published by: University of California Press on behalf of the National Council on Public History Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/tph.2003.25.2.80 . Accessed: 23/02/2012 10:14 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. University of California Press and National Council on Public History are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Public Historian. http://www.jstor.org 80 n THE PUBLIC HISTORIAN Boston Museum and Exhibit Reviews The American public increasingly receives its history from images. Thus it is incumbent upon public historians to understand the strategies by which images and artifacts convey history in exhibits and to encourage a conver- sation about language and methodology among the diverse cultural work- ers who create, use, and review these productions. The purpose of The Public Historian’s exhibit review section is to discuss issues of historical exposition, presentation, and understanding through exhibits mounted in the United States and abroad. Our aim is to provide an ongoing assess- ment of the public’s interest in history while examining exhibits designed to influence or deepen their understanding. -

Cato, Roman Stoicism, and the American 'Revolution'

Cato, Roman Stoicism, and the American ‘Revolution’ Katherine Harper A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Arts Faculty, University of Sydney. March 27, 2014 For My Parents, To Whom I Owe Everything Contents Acknowledgements ......................................................................................................... i Abstract.......................................................................................................................... iv Introduction ................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter One - ‘Classical Conditioning’: The Classical Tradition in Colonial America ..................... 23 The Usefulness of Knowledge ................................................................................... 24 Grammar Schools and Colleges ................................................................................ 26 General Populace ...................................................................................................... 38 Conclusions ............................................................................................................... 45 Chapter Two - Cato in the Colonies: Joseph Addison’s Cato: A Tragedy .......................................... 47 Joseph Addison’s Cato: A Tragedy .......................................................................... 49 The Universal Appeal of Virtue ........................................................................... -

Selected Bibliography of American History Through Biography

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 088 763 SO 007 145 AUTHOR Fustukjian, Samuel, Comp. TITLE Selected Bibliography of American History through Biography. PUB DATE Aug 71 NOTE 101p.; Represents holdings in the Penfold Library, State University of New York, College at Oswego EDRS PRICE MF-$0.75 HC-$5.40 DESCRIPTORS *American Culture; *American Studies; Architects; Bibliographies; *Biographies; Business; Education; Lawyers; Literature; Medicine; Military Personnel; Politics; Presidents; Religion; Scientists; Social Work; *United States History ABSTRACT The books included in this bibliography were written by or about notable Americans from the 16th century to the present and were selected from the moldings of the Penfield Library, State University of New York, Oswego, on the basis of the individual's contribution in his field. The division irto subject groups is borrowed from the biographical section of the "Encyclopedia of American History" with the addition of "Presidents" and includes fields in science, social science, arts and humanities, and public life. A person versatile in more than one field is categorized under the field which reflects his greatest achievement. Scientists who were more effective in the diffusion of knowledge than in original and creative work, appear in the tables as "Educators." Each bibliographic entry includes author, title, publisher, place and data of publication, and Library of Congress classification. An index of names and list of selected reference tools containing biographies concludes the bibliography. (JH) U S DEPARTMENT Of NIA1.114, EDUCATIONaWELFARE NATIONAL INSTITUTE OP EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRO DUCED ExAC ICY AS RECEIVED FROM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATIONORIGIN ATING IT POINTS OF VIEW OR OPINIONS STATED DO NOT NECESSARILYREPRE SENT OFFICIAL NATIONAL INSTITUTEOF EDUCATION POSITION OR POLICY PREFACE American History, through biograRhies is a bibliography of books written about 1, notable Americans, found in Penfield Library at S.U.N.Y. -

LIST of STATUES in the NATIONAL STATUARY HALL COLLECTION As of April 2017

history, art & archives | u. s. house of representatives LIST OF STATUES IN THE NATIONAL STATUARY HALL COLLECTION as of April 2017 STATE STATUE SCULPTOR Alabama Helen Keller Edward Hlavka Alabama Joseph Wheeler Berthold Nebel Alaska Edward Lewis “Bob” Bartlett Felix de Weldon Alaska Ernest Gruening George Anthonisen Arizona Barry Goldwater Deborah Copenhaver Fellows Arizona Eusebio F. Kino Suzanne Silvercruys Arkansas James Paul Clarke Pompeo Coppini Arkansas Uriah M. Rose Frederic Ruckstull California Ronald Wilson Reagan Chas Fagan California Junipero Serra Ettore Cadorin Colorado Florence Sabin Joy Buba Colorado John “Jack” Swigert George and Mark Lundeen Connecticut Roger Sherman Chauncey Ives Connecticut Jonathan Trumbull Chauncey Ives Delaware John Clayton Bryant Baker Delaware Caesar Rodney Bryant Baker Florida John Gorrie Charles A. Pillars Florida Edmund Kirby Smith Charles A. Pillars Georgia Crawford Long J. Massey Rhind Georgia Alexander H. Stephens Gutzon Borglum Hawaii Father Damien Marisol Escobar Hawaii Kamehameha I C. P. Curtis and Ortho Fairbanks, after Thomas Gould Idaho William Borah Bryant Baker Idaho George Shoup Frederick Triebel Illinois James Shields Leonard Volk Illinois Frances Willard Helen Mears Indiana Oliver Hazard Morton Charles Niehaus Indiana Lewis Wallace Andrew O’Connor Iowa Norman E. Borlaug Benjamin Victor Iowa Samuel Jordan Kirkwood Vinnie Ream Kansas Dwight D. Eisenhower Jim Brothers Kansas John James Ingalls Charles Niehaus Kentucky Henry Clay Charles Niehaus Kentucky Ephraim McDowell Charles Niehaus -

Sons of Liberty Patriots Or Terrorists

The Sons of Liberty : Patriots? OR Common ? Core Terrorists focused! http://www.teacherspayteachers.com/Store/Mr-Educator-A-Social-Studies-Professional Instructions: 1.) This activity can be implemented in a variety of ways. I have done this as a class debate and it works very, very well. However, I mostly complete this activity as three separate nightly homework assignments, or as three in-class assignments, followed by an in-class Socratic Seminar. The only reason I do this is because I will do the Patriots v. Loyalists: A Common Core Class Debate (located here: http://www.teacherspayteachers.com/ Product/Patriots-vs-Loyalists-A-Common-Core-Class-Debate-874989) and I don’t want to do two debates back-to-back. 2.) Students should already be familiar with the Sons of Liberty. If they aren’t, you may need to establish the background knowledge of what this group is and all about. 3.) I will discuss the questions as a class that are on the first page of the “Day 1” reading. Have classes discuss what makes someone a patriot and a terrorist. Talk about how they define these words? Can one be one without being the other? How? Talk about what both sides are after. What are the goals of terrorists? Why are they doing it? It is also helpful to bring in some outside quotes of notorious terrorists, such as Bin Laden, to show that they are too fighting for what they believe to be a just, noble cause. 4.) For homework - or as an in-class activity - assign the Day 1 reading. -

Metropolitan Boston Downtown Boston

WELCOME TO MASSACHUSETTS! CONTACT INFORMATION REGIONAL TOURISM COUNCILS STATE ROAD LAWS NONRESIDENT PRIVILEGES Massachusetts grants the same privileges EMERGENCY ASSISTANCE Fire, Police, Ambulance: 911 16 to nonresidents as to Massachusetts residents. On behalf of the Commonwealth, MBTA PUBLIC TRANSPORTATION 2 welcome to Massachusetts. In our MASSACHUSETTS DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION 10 SPEED LAW Observe posted speed limits. The runs daily service on buses, trains, trolleys and ferries 14 3 great state, you can enjoy the rolling Official Transportation Map 15 HAZARDOUS CARGO All hazardous cargo (HC) and cargo tankers General Information throughout Boston and surrounding towns. Stations can be identified 13 hills of the west and in under three by a black on a white, circular sign. Pay your fare with a 9 1 are prohibited from the Boston Tunnels. hours travel east to visit our pristine MassDOT Headquarters 857-368-4636 11 reusable, rechargeable CharlieCard (plastic) or CharlieTicket 12 DRUNK DRIVING LAWS Massachusetts enforces these laws rigorously. beaches. You will find a state full (toll free) 877-623-6846 (paper) that can be purchased at over 500 fare-vending machines 1. Greater Boston 9. MetroWest 4 MOBILE ELECTRONIC DEVICE LAWS Operators cannot use any of history and rich in diversity that (TTY) 857-368-0655 located at all subway stations and Logan airport terminals. At street- 2. North of Boston 10. Johnny Appleseed Trail 5 3. Greater Merrimack Valley 11. Central Massachusetts mobile electronic device to write, send, or read an electronic opens its doors to millions of visitors www.mass.gov/massdot level stations and local bus stops you pay on board. -

The Cradle of the American Revolution

The Cradle Of The American Revolution by The Alexandria Scottish Rite PREFACE: This research report is unique, in that the presentation is in dramatic form, rather than the usual reading of a paper. The facts are as we know them today. However, the Scottish Rite has taken a little "creative freedom" in its manner of presenting those facts. It is the hope that this will be both informative and interesting to the members of the A. Douglas Smith Jr. Lodge of Research #1949. Cast: Cradle of the American Revolution Worshipful Master — Harry Fadley Visitor #2: — James (Pete) Melvin Secretary: — William Gibbs Visitor #3: — Victor Sinclair Paul Revere: — James Petty Tyler: — Ray Burnell Visitor #1: — John McIntyre Stage: — Drew Apperson INTRODUCTION: have come up with only guess work, I figure the best way to find an answer to Narrator: LIBERTY! A PEARL OF GREAT this question is to be there and see what PRICE! Every one wants it! Only a few goes on at the time! Let’s go back in have it! Those who have it are apt to lose time to the "Cradle of The American it! The price of liberty is high! Not in Revolution" where it all began. The monetary figures, but in human lives! Cradle of The American Revolution was Thousands upon thousands of human a title given by historians to the Green lives! Dragon Tavern, a large brick building standing on Union Street in Boston, Today we are witnessing the difficult Mass. It was built in the end of the struggle for liberty all over the world; seventeenth or the beginning of the the middle East, Africa, Eastern Europe eighteenth century. -

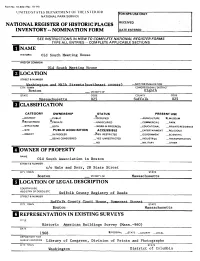

Hclassifi Cation

Form No 10-300 (Rev 10-74) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR FOR NPS USE GNtY NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES RECEIVE!} INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM DATE ENTERED SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS ____________TYPE ALL ENTRIES - COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS______ | NAME HISTORIC old South Meeting House AND/OR COMMON Old South Meeting House Q LOCATION STREETS NUMBER Washington and Milk Streets ("northeast corner) _ NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Boston _ VICINITY OF Eighth STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Massachusetts 025 Suffolk 025 HCLASSIFI CATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _DISTRICT _PUBLIC —OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE X-MUSEUM ^BUILDING(S) ^PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE _BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT —IN PROCESS -2VES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED —YES: UNRESTRICTED — INDUSTRIAL _ TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY —OTHER OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Old South Association in Boston STREETS NUMBER c/o Hale and Dorr, 28 State Street CITY. TOWN STATE Boston VICINITY OF Massachusetts LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS,ETC Suffolk County Registry of Deeds STREETS NUMBER Suffolk County Court House Somprspt Strppt CITY, TOWN STATE Boston Massachusetts REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS Historic American Buildings Survey (Mass.-960) DATE 1968 X-FEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Library of Congress, Division of Prints and Photographs CITY, TOWN STATE W&shington District of Columbia DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE ^EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED _UNALTERED ^.ORIGINAL SITE _GOOD _RUINS _XALTERED _MOVED DATE_____ _FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE Old South Meeting House, located at the northeast corner of Washington and Milk Streets in downtown Boston, was built as the second home of the Third Church in Boston, gathered in 1669. -

(Libby, Mont.), 1933-07-06

THE WESTERN NEWS, LIBBY, MONTANA Thursday, July 6, 1933. Page Six I Howe About: How I Broke Into n The Movies y Plans for a National Neitzsche Copyright by Hai C. Herrn*« Henry Ford The World Court By WILL ROGERS i By ED HOWE OW about this movie business and npHUS Spake Zarathustra," by N bow I got my start To be honeat i Pantheon * Frelderich Neitzsche, Is widely about It, I haven't yet got a real good proclaimed as one of the greatest start. And the way 1 figure things, a books ever written. As a mutter of cu fellow has to be a success before he .r&j riosity I lately looked over eight of goes lecturing and crowing about him its pages and noted the lines contain self. Ù ing ordinary common sense easily un Out here In Hollywood, they say derstandable. I found but live such you’re not a success unless you owe ■■■■■ ; fifty thousand dollars to somebody, r* v . lines In the eight pages. Neitzsche ■t had enormous common sense, but It have five cars, can develop tempera m 1 v ÿ was so corrupted by nonsense in the ment without notice or reason at all, f f'i V •' / v • M literature of the past that in his most and been mixed up in four divorce famous book the proportion of good cases and two breach-of-promlse case«. *■M V ■ i ’ I r» n « I to bad Is live to two hundred and sev Well, as a success In Hollywood, I’m mt enty-two. -

Freedom Trail N W E S

Welcome to Boston’s Freedom Trail N W E S Each number on the map is associated with a stop along the Freedom Trail. Read the summary with each number for a brief history of the landmark. 15 Bunker Hill Charlestown Cambridge 16 Musuem of Science Leonard P Zakim Bunker Hill Bridge Boston Harbor Charlestown Bridge Hatch Shell 14 TD Banknorth Garden/North Station 13 North End 12 Government Center Beacon Hill City Hall Cheers 2 4 5 11 3 6 Frog Pond 7 10 Rowes Wharf 9 1 Fanueil Hall 8 New England Downtown Crossing Aquarium 1. BOSTON COMMON - bound by Tremont, Beacon, Charles and Boylston Streets Initially used for grazing cattle, today the Common is a public park used for recreation, relaxing and public events. 2. STATE HOUSE - Corner of Beacon and Park Streets Adjacent to Boston Common, the Massachusetts State House is the seat of state government. Built between 1795 and 1798, the dome was originally constructed of wood shingles, and later replaced with a copper coating. Today, the dome gleams in the sun, thanks to a covering of 23-karat gold leaf. 3. PARK STREET CHURCH - One Park Street, Boston MA 02108 church has been active in many social issues of the day, including anti-slavery and, more recently, gay marriage. 4. GRANARY BURIAL GROUND - Park Street, next to Park Street Church Paul Revere, John Hancock, Samuel Adams, and the victims of the Boston Massacre. 5. KINGS CHAPEL - 58 Tremont St., Boston MA, corner of Tremont and School Streets ground is the oldest in Boston, and includes the tomb of John Winthrop, the first governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. -

National Statuary Hall Collection: Background and Legislative Options

National Statuary Hall Collection: Background and Legislative Options Updated December 3, 2019 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R42812 National Statuary Hall Collection: Background and Legislative Options Summary The National Statuary Hall Collection, located in the U.S. Capitol, comprises 100 statues provided by individual states to honor persons notable for their historic renown or for distinguished services. The collection was authorized in 1864, at the same time that Congress redesignated the hall where the House of Representatives formerly met as National Statuary Hall. The first statue, depicting Nathanael Greene, was provided in 1870 by Rhode Island. The collection has consisted of 100 statues—two statues per state—since 2005, when New Mexico sent a statue of Po’pay. At various times, aesthetic and structural concerns necessitated the relocation of some statues throughout the Capitol. Today, some of the 100 individual statues in the National Statuary Hall Collection are located in the House and Senate wings of the Capitol, the Rotunda, the Crypt, and the Capitol Visitor Center. Legislation to increase the size of the National Statuary Hall Collection was introduced in several Congresses. These measures would permit states to furnish more than two statues or allow the District of Columbia and the U.S. territories to provide statues to the collection. None of these proposals were enacted. Should Congress choose to expand the number of statues in the National Statuary Hall Collection, the Joint Committee on the Library and the Architect of the Capitol (AOC) may need to address statue location to address aesthetic, structural, and safety concerns in National Statuary Hall, the Capitol Visitor Center, and other areas of the Capitol.