Patna University, Patna Paper – CC-XI, Sem

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Demp Kaimur (Bhabua)

DEMP KAIMUR (BHABUA) SL SUBJECT REMARKS NO. 1 2 3 1. DISTRICT BRIEF PROFILE DISTRICT POLITICAL MAP KEY STATISTICS BRIEF NOTES ON THE DISTRICT 2. POLLING STATIONS POLLING STATIONS LOCATIONS AND BREAK UP ACCORDING TO NO. OF PS AT PSL POLLING STATION OVERVIEW-ACCESSIBILITY POLLING STATION OVERVIEW-TELECOM CONNECTIVITY POLLING STATION OVERVIEW-BASIC MINIMUM FACILITIES POLLING STATION OVERVIEW-INFRASTRUCTURE VULNERABLES PS/ELECTIORS POLLING STATION LOCATION WISE ACCESSIBILITY & REACH DETAILS POLLING STATION WISE BASIC DETAISLS RPOFILING AND WORK TO BE DONE 3. MANPOWER PLAN CADRE WISE PERSONNEL AVAILABILITY FOR EACH CATEGORY VARIOUS TEAMS REQUIRED-EEM VARIOUS TEAMS REQUIRED-OTHERS POLLING PERSONNEL REQUIRED OTHER PERSONNEL REQUIRED PERSONNEL REQUIRED & AVAILABILITY 4. COMMUNICATION PLAN 5. POLLING STAFF WELFARE NODAL OFFICERS 6. BOOTH LIST 7. LIST OF SECTOR MAGISTRATE .! .! .! .! !. .! Assembly Constituency map State : BIHAR .! .! District : KAIMUR (BHABUA) AC Name : 205 - Bhabua 2 0 3 R a m g a r h MOHANIA R a m g a r h 9 .! ! 10 1 2 ! ! ! 5 12 ! ! 4 11 13 ! MANIHAR!I 7 RUP PUR 15 3 ! 14 ! ! 6 ! 8 73 16 ! ! ! RATWAR 19 76 ! 2 0 4 ! 18 .! 75 24 7774 17 ! M o h a n ii a (( S C )) ! ! ! 20 23 DUMRAITH ! ! 78 ! 83 66 21 !82 ! ! .! 32 67 DIHARA 22 ! ! 68 ! 30 80 ! 26 ! 31 79 ! ! ! ! 81 27 29 33 ! RUIYA 70 ! 25 ! 2 0 9 69 ! 2 0 9 KOHARI ! 28 KAITHI 86 ! K a r g a h a r 85 ! 87 72 K a r g a h a r ! ! 36 35 ! 71 60 ! ! ! 34 59 52 38 37 ! ! ! ! 53 KAIMUR (BHABUA) BHABUA (BL) 64 ! ! 40 84 88 62 55 MIRIA ! ! ! ! BAHUAN 54 ! 43 39 !89 124125 63 61 ! ! -

A Study of Pre-Historic Stone Age Period of India

Journal of Arts and Culture ISSN: 0976-9862 & E-ISSN: 0976-9870, Volume 3, Issue 3, 2012, pp.-126-128. Available online at http://www.bioinfo.in/contents.php?id=53. A STUDY OF PRE-HISTORIC STONE AGE PERIOD OF INDIA DARADE S.S. Mula Education Society's Arts, Commerce & Science College, Sonai, Newasa- 414105, MS, India *Corresponding Author: Email- [email protected] Received: November 01, 2012; Accepted: December 06, 2012 Abstract- Tools crafted by proto-humans that have been dated back two million years have been discovered in the northwestern part of the subcontinent. The ancient history of the region includes some of South Asia's oldest settlements and some of its major civilizations. The earli- est archaeological site in the subcontinent is the palaeolithic hominid site in the Soan River valley. Soanian sites are found in the Sivalik region across what are now India, Pakistan, and Nepal. The Mesolithic period in the Indian subcontinent was followed by the Neolithic period, when more extensive settlement of the subcontinent occurred after the end of the last Ice Age approximately 12,000 years ago. The first confirmed semipermanent settlements appeared 9,000 years ago in the Bhimbetka rock shelters in modern Madhya Pradesh, India. Keywords- history, Mesolithic, Paleolithic, Indian Citation: Darade S.S. (2012) A Study of Pre-Historic Stone Age Period of India. Journal of Arts and Culture, ISSN: 0976-9862 & E-ISSN: 0976 -9870, Volume 3, Issue 3, pp.-126-128. Copyright: Copyright©2012 Darade S.S. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Li- cense, which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. -

Neolithic-Chalcolithic Potteries of Eastern Uttar-Pradesh

American International Journal of Available online at http://www.iasir.net Research in Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences ISSN (Print): 2328-3734, ISSN (Online): 2328-3696, ISSN (CD-ROM): 2328-3688 AIJRHASS is a refereed, indexed, peer-reviewed, multidisciplinary and open access journal published by International Association of Scientific Innovation and Research (IASIR), USA (An Association Unifying the Sciences, Engineering, and Applied Research) Neolithic-Chalcolithic Potteries of Eastern Uttar-Pradesh Dr. Shitala Prasad Singh Associate Professor, Department of Ancient History Archaeology and Culture D.D.U. Gorakhpur University, Gorakhpur, U.P., India Eastern Uttar-Pradesh (23051’ N. - 280 30’ N. and which 810 31’ E – 810 39’ E) which extends from Allahabad and Kaushambi districts of the province in the west to the Bihar-Bengal border in the east and from the Nepal tarai in the north, to the Baghelkhand region of Madhya Pradesh state in the South. The regions of eastern Uttar Pradesh covering parts or whole of the districts of Mirzapur, Sonbhadra, Sant Ravidas nagar, Varanasi, Allahabad, Kaushambi, Balia, Gonda, Bahraich, Shravasti, Balrampur, Faizabad, Ambedkar Nagar, Sultanpur, Ghazipur, Jaunpur, Pratapgarh, Basti, Siddharth Nagar, Deoria, Kushinagar, Gorakhpur, Maharajganj, Chandauli, Mau and Azamgarh. The entire region may be divided into three distinct geographical units – The Ganga Plain, the Vindhya-Kaimur ranges and the Saryupar region. The eastern Uttar Pradesh has been the cradle of Indian Culture and civilization. It is the land associated with the story of Ramayana. The deductive portions of the Mahabharta are supposed to have got their final shape in this region. The area was the nerve centre of political, economic and religious upheavels of 6th century B.C. -

Early Humans- Hunters and Gatherers Worksheet- 1

EARLY HUMANS- HUNTERS AND GATHERERS WORKSHEET- 1 QN QUESTION MA RKS 01 In the early stages, human were _____________ and nomads. 01 a. hunter-gatherers b. advanced c. singers d. musicians 02 Stone tools of _____________ Stone Age are called microliths. 01 a. Old b. New c. Middle d. India 03 One of the greatest discoveries made by early humans was of 01 a. painting b. tool making c. hunting d. fire 04 Bhimbetka, in ______________, is famous for prehistoric cave paintings. 01 a. Uttar Pradesh b. Madhya Pradesh c. Karnataka d. Orissa 05 The __________________ and Baichbal valley in Deccan have many Stone Age 01 sites. a. Burzahom b. Gufkral c. Hunsgi d. Chirand 06 What are artefacts? 01 07 What is the meaning of Palaios in Greek? 01 08 Who is a nomad? 01 09 Where is Altamira located? 01 10 Wheel was invented in which age? 01 11 Which period was known as period of transition? 01 12 True or False 01 Human evolution occurred within a very short span of time. 13 Old stone age people lived in caves and natural rock shelters. 01 14 In Chalcolithic period, humans used only metals. 01 15 Fill in the Blanks:- 01 The old stone age is known as--------------. 16 One of the oldest archaeological sites found in India is--------------- Valley in 01 Karnataka. 17 Write a note on Hunsgi. 03 18 Write a note on tools and implements of stone age people. 03 19 Why the stone age is called so? Give reasons. 03 20 What was the natural change that occurred around 9000BC? How did it help the 03 humans who lived then? 21 Which period in History is known as the Stone -

'Ff415. Atranjikhera, India, Black-And-Red 2450 ± 200 Ware Deposits 500 B.C

[RADIOCARBON, VOL. 11, No. 1, 1969, P. 188-193] TATA INSTITUTE RADIOCARBON DATE LIST VI D. P. AGRAWAL and SHEELA KUSUMGAR Tata Institute of Fundamental Research Homi Bhabha Road, Colaba, Bombay-5 This date list is comprised of archaeologic and geophysical samples. The latter are in continuation of our investigations of bomb-produced radiocarbon in atmospheric carbon dioxide reported in Tata V. We con- tinue to count samples in the form of methane; the techniques used have been described elsewhere (Agrawal et al., 1965). Radiocarbon dates presented below are based on C'4 half-life value of 5568 vr. For conversion to A.D./B.C, scale, 1950 A.D. has been used as base vr. Our modern reference standard is 95% activity of N.B.S. oxalic acid. GENERAL COMMENT Radiocarbon dating in India has been mainly confined to Neolithic and Chalcolithic cultures. Despite the dearth of datable material, at- tempts at evolving an absolute chronology for Stone-age cultures have now been started. Bone and shell samples were measured for some Micro- lithic cultures. Rock-shelters of Uttar Pradesh were dated ca. 2400 B.C. (TF-419). Adamgarh rock-shelters were dated ca. 5500 B.C. (TF-120, Radiocarbon, 1968, v. 10, p. 131). Kayatha culture of Madhya Pradesh ap- pears to date from ca. 2000 B.C. Chirand Black-and-Red ware date (TF- 444) confirms the earlier dates (Radiocarbon, 1966, v. 8, p. 442). Terdal Neolithic culture was dated ca. 1800 B.C. A megalith from Halingali was dated ca. 100 B.C. Brief summaries of these excavations are available in Ghosh (1961-1966). -

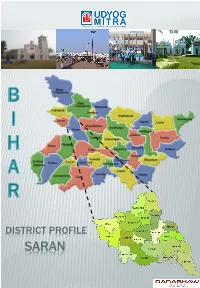

Saran Introduction

DISTRICT PROFILE SARAN INTRODUCTION Saran district is one of the thirty-eight districts of Bihar. Saran district is a part of Saran division. Saran district is also known as Chhapra district because the headquarters of this district is Chhapra. Saran district is bounded by the districts of Siwan, Gopalganj, West Champaran, Muzaffarpur, Patna, Vaishali and Bhojpur of Bihar and Ballia district of Uttar Pradesh. Important rivers flowing through Saran district are Ganga, Gandak, and Ghaghra which encircle the district from south, north east and west side respectively. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND Saran was earlier known as ‘SHARAN’ which means refuge in English, after the name given to a Stupa (pillar) built by Emperor Ashoka. Another view is that the name Saran has been derived from SARANGA- ARANYA or the deer forest since the district was famous for its forests and deer in pre-historic times. In ancient days, the present Saran division, formed a part of Kosala kingdom. According to 'Ain-E-Akbari’, Saran was one of the six Sarkars/ revenue divisions, constituting the province of Bihar. By 1666, the Dutch established their trade in saltpetre at Chhapra. Saran was one of the oldest and biggest districts of Bihar. In 1829, Saran along with Champaran, was included in the Patna Division. Saran was separated from Champaran in 1866 when Champaran district was constituted. In 1981, the three subdivisions of the old Saran district namely Saran, Siwan and Gopalganj became independent districts which formed a part of Saran division. There are a few villages in Saran which are known for their historical and social significance. -

ISSUE XIII Jamshedpur Research Review Govt Regd

Jamshedpur Research Review * ISSN 2320-2750 * YEAR IV VOL. IV ISSUE XIII Jamshedpur Research Review Govt Regd. English Quarterly Multi-disciplinary International Research Journal RNI – JHA/ENG/2013/53159 Year IV : Issue XIII ISSN: 2320-2750 December 2015-February 2016 Postal Registration No.-G/SBM-49/2016 Distributors: Jamshedpur Research Review, 62, Block No.-3, Dateline: 1 December 2015-28 February Shastrinagar, Kadma, Jamshedpur, Jharkhand, 2016 Pin-831005, Ph.09334077378, Year IV: : Issue XIII [email protected] Place: Jamshedpur Language: English Periodicity: Quarterly © 2015 Jamshedpur Research Review Price: Rs.150 No. of Pages:144 Nationality of the editor: Indian No part of this publication can be reproduced in Editor: Mithilesh Kumar Choubey any form or by any means without the prior Owner: Gyanjyoti Educational and permission of the publishers Research Foundation (Trust), 62, Block ISSN: 2320-2750 No.-3, Shastrinagar, Kadma, Jamshedpur, Jharkhand, Pin-831005. RNI- JHAENG/2013/53159 Publisher: Mithilesh Kumar Choubey Nationality of the Publisher: Indian Postal Registration No.: G/SBM 49/2016-18 Printer: Mithilesh Kumar Choubey Jamshedpur Research Review is a registered Nationality of the Publisher: Indian open market Research Journal, registered with Printing Press: Gyanjyoti printing press, Registrar, Newspapers in India, Ministry of Gyanjyoti Educational and Research Information and Broadcasting, Govt of India. Foundation (Trust), 62, Block No.-3, Matters related to research paper such as Shastrinagar, Kadma, Jamshedpur, selection/acceptance/rejection etc. are decided by Jharkhand, Pin-831005. editorial board on the basis of recommendations Declaration: Owner of Jamshedpur Research of paper review committee. In this regard final decision making body will be the Editor-in –Chief Review, English Quarterly is Gyanjyoti Educational that will be binding to all. -

2. the Geographical Setting and Pre-Historic Cultures of India

MODULE - 1 Ancient India 2 Notes THE GEOGRAPHICAL SETTING AND PRE-HISTORIC CULTURES OF INDIA The history of any country or region cannot be understood without some knowledge of its geography. The history of the people is greatly conditioned by the geography and environment of the region in which they live. The physical geography and envi- ronmental conditions of a region include climate, soil types, water resources and other topographical features. These determine the settlement pattern, population spread, food products, human behaviour and dietary habits of a region. The Indian subcontinent is gifted with different regions with their distinct geographical features which have greatly affected the course of its history. Geographically speaking the Indian subcontinent in ancient times included the present day India, Bangladesh, Nepal, Bhutan and Pakistan. On the basis of geographical diversities the subcontinent can be broadly divided into the follow- ing main regions. These are: (i) The Himalayas (ii) The River Plains of North India (iii) The Peninsular India OBJECTIVES After studying this lesson, you will be able to: explain the physical divisions of Indian subcontinent; recognize the distinct features of each region; understand why some geographical areas are more important than the others; define the term environment; establish the relationship between geographical features and the historical devel- opments in different regions; define the terms prehistory, prehistoric cultures, and microliths; distinguish between the lower, middle and upper Palaeolithic age on the basis of the tools used; explain the Mesolithic age as a phase of transition on the basis of climate and the 10 HISTORY The Geographical Setting and pre-historic MODULE - 1 Ancient India tools used; explain the Neolithic age and its chief characteristics; differentiate between Palaeolithic and Neolithic periods and learn about the Prehistoric Art. -

The Upper Ganges River (Downstream)

THE UPPER GANGES RIVER (DOWNSTREAM) In late 2019 we will inaugurate an ‘all Ganges’ voyage of one thousand miles from Kolkata to Varanasi. Though in the days of the British Raj paddle steamers plied this route on a regular basis, with the advent of the railways in India river navigation was abandoned and the rivers were allowed to silt up. Now thanks to a multi-million dollar investment from the Indian Government channels have been dredged and buoyed and hi tech GPS based aids installed enabling seasonal navigation. Varanasi, said to be the oldest inhabited city on the planet is the most sacred city of Hinduism and a place of overwhelming beauty at the same time poignantly moving with its cremation ghats. Varanasi is surely the goal of any ‘passage to India’ and at the other end of the holy river stands Kolkata, in all its Raj-like magnificence. Between lies several of the most important Buddhist sites including Sarnath, Nalanda and Bodh Gaya and cities great and small and between urban centres and great pilgrim sites are expanses of empty river teeming with bird life, not to mention the Gangeatic dolphin. number of staterooms from sixteen to fourteen to create an No vessel could be more appropriate for a voyage on ‘All the enlarged indoor saloon / dining area as winter cruising in India Ganges’ than the much-loved Katha Pandaw, constructed can be chilly first thing. originally in Vietnam in 2008 that has seen service there, in Cambodia and in recent years in Burma. Refitted for expedition ITINERARY sailings in India, we have reduced the DAY 1 VARANASI The oldest and holiest city of India established in the 11th century BC and today with over 2,000 living temples. -

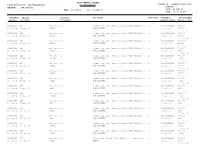

East Cenyral Railway 10 Days Report Section

EAST CENYRAL RAILWAY INSTALLATION FOR : HJP/DNR/SEE/SPJ 10 DAYS REPORT REPORT ID : AFDAYS10_TEST_1904 SECTION : 160 and 161 PAGE NO : 1 FROM : 01-JAN-14 TO : 12-FEB-14 DATE : 12-FEB-14 TIME : 03:52:18 PM Co6number Billid Billdesc Partyname Co6status Co7number Chequenumber Co6date Billdate Billamount Co6statusdate amount & Date 160002645 851 MEDICAL BILL PANCHRATNA DAWA KENDRA AC NO 4037002100004012 P C 201316000605 783837 01-JAN-14 18-OCT-13 76734 N B HAJIPUR 13-JAN-14 76734 13-JAN-14 160002646 866 MEDICAL BILL PANCHRATNA DAWA KENDRA AC NO 4037002100004012 P C 201316000606 783837 01-JAN-14 07-NOV-13 20160 N B HAJIPUR 13-JAN-14 20160 13-JAN-14 160002647 878 MEDICAL BILL PANCHRATNA DAWA KENDRA AC NO 4037002100004012 P C 201316000605 783837 01-JAN-14 22-NOV-13 49680 N B HAJIPUR 13-JAN-14 49680 13-JAN-14 160002648 889 MEDICAL BILL PANCHRATNA DAWA KENDRA AC NO 4037002100004012 P C 201316000605 783837 01-JAN-14 27-NOV-13 22837 N B HAJIPUR 13-JAN-14 22837 13-JAN-14 160002649 894 MEDICAL BILL PANCHRATNA DAWA KENDRA AC NO 4037002100004012 P C 201316000606 783837 01-JAN-14 27-NOV-13 13154 N B HAJIPUR 13-JAN-14 13154 13-JAN-14 160002650 841 MEDICAL BILL PANCHRATNA DAWA KENDRA AC NO 4037002100004012 P C 201316000605 783837 01-JAN-14 08-OCT-13 23460 N B HAJIPUR 13-JAN-14 23460 13-JAN-14 160002651 856 MEDICAL BILL PANCHRATNA DAWA KENDRA AC NO 4037002100004012 P C 201316000605 783837 01-JAN-14 23-SEP-13 36750 N B HAJIPUR 13-JAN-14 36750 13-JAN-14 160002652 842 MEDICAL BILL PANCHRATNA DAWA KENDRA AC NO 4037002100004012 P C 201316000605 783837 01-JAN-14 -

Bihar & Jharkhand

© Lonely Planet Publications 549 Bihar & Jharkhand The birthplace of Buddhism in India, Bihar occupies an important place in India’s cultural and spiritual history. Siddhartha Gautama – the Buddha – spent much of his life here and attained enlightenment beneath a bodhi tree at Bodhgaya – making it the most significant Buddhist pilgrimage site in the world. Little more than a rural village, Bodhgaya is peppered with international monasteries and attracts devotees from around the world to meditate and soak up the powerful ambience. Following a trail of ancient and modern Buddhist sites, you can visit the extensive ruins of Nalanda, one of the ancient world’s first universities, the many shrines and temples at nearby Rajgir, and the great Ashokan pillar at Vaishali. After a controversial vote in the Indian Parliament in August 2000, Bihar was split along tribal lines, creating the new southern state of Jharkhand. Home to numerous waterfalls and lush forests, Jharkhand is notable as the key Jain pilgrimage site in east India, though the state’s best-kept secret is Betla National Park, where you can ride atop an elephant into the forest’s depths in search of an elusive tiger. Unfortunately, the twin states of Bihar and Jharkhand are one of India’s poorest and most troubled regions. Wracked by widespread government corruption, sporadic intercaste warfare, kidnappings, extortion, banditry and Naxalite violence, Bihar remains the least lit- erate and most lawless part of India – maligned as a basket case and the antithesis of the economically prosperous ‘new India’. All this keeps it well off most travellers’ radars, but don’t be put off. -

Indian Archaeology 1963-64 a Review

INDIAN ARCHAEOLOGY 1963-64 —A REVIEW EDITED BY A. GHOSH Director General of Archaeology in India ARCHAEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF INDIA GOVERNMENT OF INDIA NEW DELHI 1967 Price : Rupees Ten 1967 COPYRIGHT ARCHAEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF I N D I A GOVERNMENT OF INDIA PRINTED AT THE GOVERNMENT OF INDIA PRESS, FARIDABAD ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This annual Review, the eleventh in the series, incorporates material received from different contributors to whom I am grateful for their co-operation. They are no doubt responsible for the facts and interpretation of data supplied by them. At the same time, I would hold myself responsible for any editorial errors that might have unwittingly crept in. I thank my colleagues and staff in the Archaeological Survey of India for their help in editing the Review and seeing it through the press. New Delhi : The 21st March 1967 A. GHOSH (iii) CONTENTS PAGE I. Explorations and excavations 1 Andhra Pradesh, 1 ; Assam, 4 ; Bihar, 5 ; Gujarat, 9 ; Kerala, 13 ; Madhya Pradesh, 14 ; Madras, 17 ; Maharashtra, 21 ; Mysore, 23 ; Orissa, 27 ; Panjab, 27; Rajasthan, 28 ; Uttar Pradesh, 39 ; West Bengal, 59. II. Epigraphy ........................................................................................................................ 66 Sanskritic and Dravidic inscriptions, 66. Andhra Pradesh, 66 ; Bihar, 68 ; Delhi, 68 ; Goa, 68 ; Gujarat, 69 ; Himachal Pradesh, 69; Kerala, 69 ; Madhya Pradesh, 70 ; Madras, 71 ; Maharashtra, 72 ; Mysore, 72; Orissa, 73 ; Rajasth an, 74; Uttar Pradesh, 74. Arabic and Persian inscriptions, 75. Andhra Pradesh, 75 ; Bihar, 75 ; Delhi, 76 ; Goa, 76 ; Gujarat, 76 ; Madhya Pradesh, 77 ; Madras, 78 ; Maharashtra, 79 ; Mysore, 80 ; Panjab, 81 ; Rajasthan, 81 ; Uttar Pradesh, 81 ; West B«ngal, 83. III. Numismatics and treasure-trove ....................................................................................