Black and Red Ware Culture: a Reappraisal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Study of the Early Vedic Age in Ancient India

Journal of Arts and Culture ISSN: 0976-9862 & E-ISSN: 0976-9870, Volume 3, Issue 3, 2012, pp.-129-132. Available online at http://www.bioinfo.in/contents.php?id=53. A STUDY OF THE EARLY VEDIC AGE IN ANCIENT INDIA FASALE M.K.* Department of Histroy, Abasaheb Kakade Arts College, Bodhegaon, Shevgaon- 414 502, MS, India *Corresponding Author: Email- [email protected] Received: December 04, 2012; Accepted: December 20, 2012 Abstract- The Vedic period (or Vedic age) was a period in history during which the Vedas, the oldest scriptures of Hinduism, were composed. The time span of the period is uncertain. Philological and linguistic evidence indicates that the Rigveda, the oldest of the Vedas, was com- posed roughly between 1700 and 1100 BCE, also referred to as the early Vedic period. The end of the period is commonly estimated to have occurred about 500 BCE, and 150 BCE has been suggested as a terminus ante quem for all Vedic Sanskrit literature. Transmission of texts in the Vedic period was by oral tradition alone, and a literary tradition set in only in post-Vedic times. Despite the difficulties in dating the period, the Vedas can safely be assumed to be several thousands of years old. The associated culture, sometimes referred to as Vedic civilization, was probably centred early on in the northern and northwestern parts of the Indian subcontinent, but has now spread and constitutes the basis of contemporary Indian culture. After the end of the Vedic period, the Mahajanapadas period in turn gave way to the Maurya Empire (from ca. -

A Study of Pre-Historic Stone Age Period of India

Journal of Arts and Culture ISSN: 0976-9862 & E-ISSN: 0976-9870, Volume 3, Issue 3, 2012, pp.-126-128. Available online at http://www.bioinfo.in/contents.php?id=53. A STUDY OF PRE-HISTORIC STONE AGE PERIOD OF INDIA DARADE S.S. Mula Education Society's Arts, Commerce & Science College, Sonai, Newasa- 414105, MS, India *Corresponding Author: Email- [email protected] Received: November 01, 2012; Accepted: December 06, 2012 Abstract- Tools crafted by proto-humans that have been dated back two million years have been discovered in the northwestern part of the subcontinent. The ancient history of the region includes some of South Asia's oldest settlements and some of its major civilizations. The earli- est archaeological site in the subcontinent is the palaeolithic hominid site in the Soan River valley. Soanian sites are found in the Sivalik region across what are now India, Pakistan, and Nepal. The Mesolithic period in the Indian subcontinent was followed by the Neolithic period, when more extensive settlement of the subcontinent occurred after the end of the last Ice Age approximately 12,000 years ago. The first confirmed semipermanent settlements appeared 9,000 years ago in the Bhimbetka rock shelters in modern Madhya Pradesh, India. Keywords- history, Mesolithic, Paleolithic, Indian Citation: Darade S.S. (2012) A Study of Pre-Historic Stone Age Period of India. Journal of Arts and Culture, ISSN: 0976-9862 & E-ISSN: 0976 -9870, Volume 3, Issue 3, pp.-126-128. Copyright: Copyright©2012 Darade S.S. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Li- cense, which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. -

Neolithic-Chalcolithic Potteries of Eastern Uttar-Pradesh

American International Journal of Available online at http://www.iasir.net Research in Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences ISSN (Print): 2328-3734, ISSN (Online): 2328-3696, ISSN (CD-ROM): 2328-3688 AIJRHASS is a refereed, indexed, peer-reviewed, multidisciplinary and open access journal published by International Association of Scientific Innovation and Research (IASIR), USA (An Association Unifying the Sciences, Engineering, and Applied Research) Neolithic-Chalcolithic Potteries of Eastern Uttar-Pradesh Dr. Shitala Prasad Singh Associate Professor, Department of Ancient History Archaeology and Culture D.D.U. Gorakhpur University, Gorakhpur, U.P., India Eastern Uttar-Pradesh (23051’ N. - 280 30’ N. and which 810 31’ E – 810 39’ E) which extends from Allahabad and Kaushambi districts of the province in the west to the Bihar-Bengal border in the east and from the Nepal tarai in the north, to the Baghelkhand region of Madhya Pradesh state in the South. The regions of eastern Uttar Pradesh covering parts or whole of the districts of Mirzapur, Sonbhadra, Sant Ravidas nagar, Varanasi, Allahabad, Kaushambi, Balia, Gonda, Bahraich, Shravasti, Balrampur, Faizabad, Ambedkar Nagar, Sultanpur, Ghazipur, Jaunpur, Pratapgarh, Basti, Siddharth Nagar, Deoria, Kushinagar, Gorakhpur, Maharajganj, Chandauli, Mau and Azamgarh. The entire region may be divided into three distinct geographical units – The Ganga Plain, the Vindhya-Kaimur ranges and the Saryupar region. The eastern Uttar Pradesh has been the cradle of Indian Culture and civilization. It is the land associated with the story of Ramayana. The deductive portions of the Mahabharta are supposed to have got their final shape in this region. The area was the nerve centre of political, economic and religious upheavels of 6th century B.C. -

Patna University, Patna Paper – CC-XI, Sem

Chirand Chalcolithic Culture Dr. Dilip Kumar Assistant Professor (Guest) Dept. of Ancient Indian History & Archaeology, Patna University, Patna Paper – CC-XI, Sem. – III With the end of the Neolithic Age, several cultures started using metal, mostly copper and low grade bronze. The culture based on the use of copper and stone was termed as Chalcolithic meaning stone-copper Phase. In India, it spanned around 2000 BC to 700 BC. This culture was mainly seen in Pre-Harappan phase, but at many places it extended to Post-Harappan phase too. The people were mostly rural and lived near hills and rivers. The Chalcolithic culture corresponds to the farming communities, namely Kayatha, Ahar or Banas, Malwa, and Jorwe. The term Chalcolithic is a combination of two words- Chalco+Lithic was derived from the Greek words "khalkos" + "líthos" which means "copper" and "stone" or Copper Age. It is also known as the Eneolithic (from Latin aeneus "of copper") is an archaeological period that is usually considered to be part of the broader Neolithic (although it was originally defined as a transition between the Neolithic and the Bronze Age). Chirand is an archaeological site in the Saran district of Bihar, situated on the northern bank of the Ganga River. It has a large pre-historic mound, known for its continuous archaeological record from the Neolithic age to the reign of the Pal dynasty who ruled during the pre-medieval period; the excavations in Chirand have revealed stratified Neolithic and Iron Age settlements, transitions in human habitation patterns dating from 2500 BC to 30 AD. -

Early Humans- Hunters and Gatherers Worksheet- 1

EARLY HUMANS- HUNTERS AND GATHERERS WORKSHEET- 1 QN QUESTION MA RKS 01 In the early stages, human were _____________ and nomads. 01 a. hunter-gatherers b. advanced c. singers d. musicians 02 Stone tools of _____________ Stone Age are called microliths. 01 a. Old b. New c. Middle d. India 03 One of the greatest discoveries made by early humans was of 01 a. painting b. tool making c. hunting d. fire 04 Bhimbetka, in ______________, is famous for prehistoric cave paintings. 01 a. Uttar Pradesh b. Madhya Pradesh c. Karnataka d. Orissa 05 The __________________ and Baichbal valley in Deccan have many Stone Age 01 sites. a. Burzahom b. Gufkral c. Hunsgi d. Chirand 06 What are artefacts? 01 07 What is the meaning of Palaios in Greek? 01 08 Who is a nomad? 01 09 Where is Altamira located? 01 10 Wheel was invented in which age? 01 11 Which period was known as period of transition? 01 12 True or False 01 Human evolution occurred within a very short span of time. 13 Old stone age people lived in caves and natural rock shelters. 01 14 In Chalcolithic period, humans used only metals. 01 15 Fill in the Blanks:- 01 The old stone age is known as--------------. 16 One of the oldest archaeological sites found in India is--------------- Valley in 01 Karnataka. 17 Write a note on Hunsgi. 03 18 Write a note on tools and implements of stone age people. 03 19 Why the stone age is called so? Give reasons. 03 20 What was the natural change that occurred around 9000BC? How did it help the 03 humans who lived then? 21 Which period in History is known as the Stone -

'Ff415. Atranjikhera, India, Black-And-Red 2450 ± 200 Ware Deposits 500 B.C

[RADIOCARBON, VOL. 11, No. 1, 1969, P. 188-193] TATA INSTITUTE RADIOCARBON DATE LIST VI D. P. AGRAWAL and SHEELA KUSUMGAR Tata Institute of Fundamental Research Homi Bhabha Road, Colaba, Bombay-5 This date list is comprised of archaeologic and geophysical samples. The latter are in continuation of our investigations of bomb-produced radiocarbon in atmospheric carbon dioxide reported in Tata V. We con- tinue to count samples in the form of methane; the techniques used have been described elsewhere (Agrawal et al., 1965). Radiocarbon dates presented below are based on C'4 half-life value of 5568 vr. For conversion to A.D./B.C, scale, 1950 A.D. has been used as base vr. Our modern reference standard is 95% activity of N.B.S. oxalic acid. GENERAL COMMENT Radiocarbon dating in India has been mainly confined to Neolithic and Chalcolithic cultures. Despite the dearth of datable material, at- tempts at evolving an absolute chronology for Stone-age cultures have now been started. Bone and shell samples were measured for some Micro- lithic cultures. Rock-shelters of Uttar Pradesh were dated ca. 2400 B.C. (TF-419). Adamgarh rock-shelters were dated ca. 5500 B.C. (TF-120, Radiocarbon, 1968, v. 10, p. 131). Kayatha culture of Madhya Pradesh ap- pears to date from ca. 2000 B.C. Chirand Black-and-Red ware date (TF- 444) confirms the earlier dates (Radiocarbon, 1966, v. 8, p. 442). Terdal Neolithic culture was dated ca. 1800 B.C. A megalith from Halingali was dated ca. 100 B.C. Brief summaries of these excavations are available in Ghosh (1961-1966). -

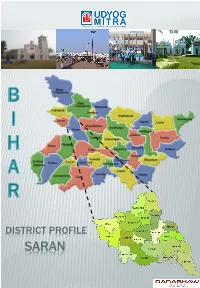

Saran Introduction

DISTRICT PROFILE SARAN INTRODUCTION Saran district is one of the thirty-eight districts of Bihar. Saran district is a part of Saran division. Saran district is also known as Chhapra district because the headquarters of this district is Chhapra. Saran district is bounded by the districts of Siwan, Gopalganj, West Champaran, Muzaffarpur, Patna, Vaishali and Bhojpur of Bihar and Ballia district of Uttar Pradesh. Important rivers flowing through Saran district are Ganga, Gandak, and Ghaghra which encircle the district from south, north east and west side respectively. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND Saran was earlier known as ‘SHARAN’ which means refuge in English, after the name given to a Stupa (pillar) built by Emperor Ashoka. Another view is that the name Saran has been derived from SARANGA- ARANYA or the deer forest since the district was famous for its forests and deer in pre-historic times. In ancient days, the present Saran division, formed a part of Kosala kingdom. According to 'Ain-E-Akbari’, Saran was one of the six Sarkars/ revenue divisions, constituting the province of Bihar. By 1666, the Dutch established their trade in saltpetre at Chhapra. Saran was one of the oldest and biggest districts of Bihar. In 1829, Saran along with Champaran, was included in the Patna Division. Saran was separated from Champaran in 1866 when Champaran district was constituted. In 1981, the three subdivisions of the old Saran district namely Saran, Siwan and Gopalganj became independent districts which formed a part of Saran division. There are a few villages in Saran which are known for their historical and social significance. -

Iron Age Material Culture in South Asia – Analysis Ancient Asia and Context of Recently Discovered Slag Sites in Northwest Kashmir (Baramulla District) in India

Yatoo, M A 2015 Iron Age Material Culture in South Asia – Analysis Ancient Asia and Context of Recently Discovered Slag Sites in Northwest Kashmir (Baramulla District) in India. Ancient Asia, 6: 3, pp. 1-8, DOI: http://dx.doi. org/10.5334/aa.12322 RESEARCH PAPER Iron Age Material Culture in South Asia – Analysis and Context of Recently Discovered Slag Sites in Northwest Kashmir (Baramulla District) in India Mumtaz A. Yatoo* This paper deals with presence or absence of Iron Age material culture and explores the development of Iron Age in northwest Kashmir (Baramulla District). It has been noted from the previous surveys that a chronological gap existed (c. 1000 BCE – 100 CE), which roughly equates to the Iron Age in Kashmir (Yatoo 2005; Yatoo 2012). Furthermore, considering that there is very little evidence of Iron Age material culture from the few excavated (or explored) sites in Kashmir, there is a debate about the very presence of Iron Age in Kashmir. The little information we have about Iron Age material culture from key sites in Kashmir (such as a few sherds of NBPW, some iron artefacts and slag at one site), has been largely dismissed as imports and lacked serious attention by scholars. It was therefore difficult to build any comparisons in the material culture for the present study. Instead the Iron Age material culture in other parts of South Asia, such as the Indian plains and northern regions of Pakistan, are discussed, as these regions have documented evidence of iron and its associated material culture but very few have archaeometallurgical evidence. -

The Panchala Maha Utsav a Tribute to the Rich Cultural Heritage of Auspicious Panchala Desha and It’S Brave Princess Draupadi

Commemorting 10years with The Panchala Maha Utsav A Tribute to the rich Cultural Heritage of auspicious Panchala Desha and It’s brave Princess Draupadi. The First of its kind Historic Celebration We Enter The Past, To Create Opportunities For The Future A Report of Proceedings Of programs from 15th -19th Dec 2013 At Dilli Haat and India International Center 2 1 Objective Panchala region is a rich repository of tangible & intangible heritage & culture and has a legacy of rich history and literature, Kampilya being a great centre for Vedic leanings. Tangible heritage is being preserved by Archaeological Survey of India (Kampilya , Ahichchetra, Sankia etc being Nationally Protected Sites). However, negligible or very little attention has been given to the intangible arts & traditions related to the Panchala history. Intangible heritage is a part of the living traditions and form a very important component of our collective cultures and traditions, as well as History. As Draupadi Trust completed 10 years on 15th Dec 2013, we celebrated our progressive woman Draupadi, and the A Master Piece titled Parvati excavated at Panchala Desha (Ahichhetra Region) during the 1940 excavation and now a prestigious display at National Museum, Rich Cultural Heritage of her historic New Delhi. Panchala Desha. We organised the “Panchaala Maha Utsav” with special Unique Features: (a) Half Moon indicating ‘Chandravanshi’ focus on the Vedic city i.e. Draupadi’s lineage from King Drupad, (b) Third Eye of Shiva, (c) Exquisite Kampilya. The main highlights of this Hairstyle (showing Draupadi’s love for her hair). MahaUtsav was the showcasing of the Culture, Crafts and other Tangible and Intangible Heritage of this rich land, which is on the banks of Ganga, this reverend land of Draupadi’s birth, land of Sage Kapil Muni, of Ayurvedic Gospel Charac Saminhita, of Buddha & Jain Tirthankaras, the land visited by Hiuen Tsang & Alexander Cunningham, and much more. -

Unit 10 Chalcolithic and Early Iron Age-I

UNIT 10 CHALCOLITHIC AND EARLY IRON AGE-I Structure 10.0 Objectives 10.1 Introduction 10.2 Ochre Coloured Pottery Culture 10.3 The Problems of Copper Hoards 10.4 Black and Red Ware Culture 10.5 Painted Grey Ware Culture 10.6 Northern Black Polished Ware Culture 10.6.1 Structures 10.6.2 Pottery 10.6.3 Other Objects 10.6.4 Ornaments 10.6.5 Terracotta Figurines 10.6.6 Subsistence Economy and Trade 10.7 Chalcolithic Cultures of Western, Central and Eastern India 10.7.1 Pottery: Diagnostic Features 10.7.2 Economy 10.7.3 Houses and Habitations 10.7.4 Other 'characteristics 10.7.5 Religion/Belief Systems 10.7.6 Social Organization 10.8 Let Us Sum Up 10.9 Key Words 10.10 Answers to Check Your Progress Exercises 10.0 OBJECTIVES In Block 2, you have learnt about'the antecedent stages and various aspects of Harappan culture and society. You have also read about its geographical spread and the reasons for its decline and diffusion. In this unit we shall learn about the post-Harappan, Chalcolithic, and early Iron Age Cultures of northern, western, central and eastern India. After reading this unit you will be able to know about: a the geographical location and the adaptation of the people to local conditions, a the kind of houses they lived in, the varieties of food they grew and the kinds of tools and implements they used, a the varietie of potteries wed by them, a the kinds of religious beliefs they had, and a the change occurring during the early Iron age. -

Emergence of Iron in India : Archaeological Perspective

0 2001 NML Jamshedpur 831 007, India; Metallurcy in India: A Retrospective; (ISBN: 81-87053-56-7); Eds: P. Ramachandra Rao and N.G. Goswami; pp. 25-51. Emergence of Iron in India : Archaeological Perspective V. Tripathi Professor in Metallurgy, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi. India. ABSTRACT The evidence of iron in ancient India today weighs heavily in favour of its indigenous origin. It is clearly borne out by an examination of literary, archaeological and metallurgical data on the subject. The metallurgical skill shows clear-cut phases of technological evolution as is evident in furnace design. The technological growth appears to be inter-related with socio-economic and cultural upsurgence. Key words : Origin, Literary evidence, Archaeological evidence, Metallurgy, Furnace. INTRODUCTION Iron metallurgy in India had a glorious past. This should be attributed to the ingenuity and sustained effort of the craftsmen of ancient India. One comes across references of Indian swords being presented to ambassadors (Ktesia-g) way back in 5th century BC and to the kings and warriors like Alexandre in 4th cent. BC The wootz steel, once famous as Damascus steel, a 'prized commodity in the ancient world, originated in India. The Mehrauli Iron Pillar (Delhi) has been called the 'rustless wonder' by a modern metallurgistoi. This massive structure has withstood the weather and exposure to elements for thousands of years. Throughout the medieval ages the tradition continued well into the British period. •It was a household industry in Mysore during -Tip-u-rule whose sword has generated immense interest among experts on iron. During 1857 the British found it difficult to destroy the Indian swords confiscated from defeated Indian armies. -

2. the Geographical Setting and Pre-Historic Cultures of India

MODULE - 1 Ancient India 2 Notes THE GEOGRAPHICAL SETTING AND PRE-HISTORIC CULTURES OF INDIA The history of any country or region cannot be understood without some knowledge of its geography. The history of the people is greatly conditioned by the geography and environment of the region in which they live. The physical geography and envi- ronmental conditions of a region include climate, soil types, water resources and other topographical features. These determine the settlement pattern, population spread, food products, human behaviour and dietary habits of a region. The Indian subcontinent is gifted with different regions with their distinct geographical features which have greatly affected the course of its history. Geographically speaking the Indian subcontinent in ancient times included the present day India, Bangladesh, Nepal, Bhutan and Pakistan. On the basis of geographical diversities the subcontinent can be broadly divided into the follow- ing main regions. These are: (i) The Himalayas (ii) The River Plains of North India (iii) The Peninsular India OBJECTIVES After studying this lesson, you will be able to: explain the physical divisions of Indian subcontinent; recognize the distinct features of each region; understand why some geographical areas are more important than the others; define the term environment; establish the relationship between geographical features and the historical devel- opments in different regions; define the terms prehistory, prehistoric cultures, and microliths; distinguish between the lower, middle and upper Palaeolithic age on the basis of the tools used; explain the Mesolithic age as a phase of transition on the basis of climate and the 10 HISTORY The Geographical Setting and pre-historic MODULE - 1 Ancient India tools used; explain the Neolithic age and its chief characteristics; differentiate between Palaeolithic and Neolithic periods and learn about the Prehistoric Art.