Tu Quoque Philippi: Eannatum's Phalanx

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Battle of Hastings

The Battle of Hastings The Battle of Hastings is one of the most famous battles in English history. What Caused the Battle? In 1066, three men were fighting to be King of England: William of Normandy, Harold Godwinson and Harald Hardrada. Harold Godwinson was crowned king on 6th January 1066. William and Harald were not happy. They both prepared to invade England in order to kill King Harold and become king themselves. Harald Hardrada attacked from the north of England on 25th September. However, he was killed in battle and his army was defeated by King Harold’s army. King Harold was then told that William of Normandy had landed in the south and was attacking the surrounding countryside. King Harold was furious and marched his tired troops 300 kilometres to meet them. Eight days later, Harold and his men reached London. William sent a messenger to London. The message tried to get Harold to accept William as the true King of England. Harold refused and was angered by William’s request. Harold was advised to wait before attacking William and his army. His troops were very tired and they needed time to prepare for the battle. However, Harold ignored this advice and on 13th October, his troops arrived in Hastings ready to fight. They captured a hill (now known as Battle Hill) and set up a fortress surrounded with sharp stakes stuck in a deep ditch. Harold ordered his forces to stay in their positions no matter what happened. The Battle of Hastings On 14th October, the battle began. -

After the Battle Is Over: the Stele of the Vultures and the Beginning Of

To raise the ofthe natureof narrative is to invite After the Battle Is Over: The Stele question reflectionon the verynature of culture. Hayden White, "The Value of Narrativity . ," 1981 of the Vultures and the Beginning of Historical Narrative in the Art Definitions of narrative, generallyfalling within the purviewof literarycriticism, are nonethelessimportant to of the Ancient Near East arthistorians. From the simpleststarting point, "for writing to be narrative,no moreand no less thana tellerand a tale are required.'1 Narrativeis, in otherwords, a solutionto " 2 the problemof "how to translateknowing into telling. In general,narrative may be said to make use ofthird-person cases and of past tenses, such that the teller of the story standssomehow outside and separatefrom the action.3But IRENE J. WINTER what is importantis thatnarrative cannot be equated with thestory alone; it is content(story) structured by the telling, University of Pennsylvania forthe organization of the story is whatturns it into narrative.4 Such a definitionwould seem to providefertile ground forart-historical inquiry; for what, after all, is a paintingor relief,if not contentordered by the telling(composition)? Yet, not all figuraiworks "tell" a story.Sometimes they "refer"to a story;and sometimesthey embody an abstract concept withoutthe necessaryaction and settingof a tale at all. For an investigationof visual representation, it seems importantto distinguishbetween instancesin which the narrativeis vested in a verbal text- the images servingas but illustrationsof the text,not necessarily"narrative" in themselves,but ratherreferences to the narrative- and instancesin whichthe narrativeis located in the represen- tations,the storyreadable throughthe images. In the specificcase of the ancientNear East, instances in whichnarrative is carriedthrough the imageryitself are rare,reflecting a situationfundamentally different from that foundsubsequently in the West, and oftenfrom that found in the furtherEast as well. -

Unit 6: Ancient Sumer Ancient Civilizations Options 5000BCE – 1940BCE

Unit 6: Ancient Sumer Ancient Civilizations Options 5000BCE – 1940BCE Period Overview The Ancient Sumer civilization grew up around the Euphretes and Tigris rivers in Mesopotamia (modern-day Iraq), because of its natural fertility. It is often called the ‘cradle of civilization’. By 3000BCE the area was inhabited by 12 main city states, with most developing a monarchical system. The fertility of the soil in the area allowed the societies to devote their attention to other things, and so the Sumer is renowned for its innovation. The clock system we use today of 60-minute hours was devised by Ancient Sumerians, as was writing and the recording of a number system. The civilization began to decline after the invasion of the city states by Sargon I in around 2330BCE, bringing them into the Akkadian Empire. A later Sumerian revival occurred in the area. Life in Ancient Sumer Changing Times Although starting out as small villages and groups of During the 5th Millennium BCE, Sumerians began to hunter-gatherers, Sumer is notable because of its develop large towns which became city-states. This development into a chain of cities. Within the cities the was made by possible by their systems of cultivation of advantages of communal living soon allowed crops, including some of the world’s earliest irrigation individuals to take on other roles than farming, and a systems. These developing communities then were society of classes developed. At the top of the class able to devote time to pursuits other than gathering system were the king and his family, and the priests. -

Entemena Was the Fifth Ruler of the So-Called Urnanse Dynasty in The

ON THE MEANING OF THE OFFERINGS FOR THE STATUE OF ENTEMENA TOSHIKO KOBAYASHI I. Introduction Entemena was the fifth ruler of the so-called Urnanse dynasty in the Pre- Sargonic Lagas and his reign seemed to be prosperous as same as that of Ean- natum, his uncle. After the short reign of Enannatum II, his son, Enentarzi who had been sanga (the highest administrator) of the temple of Ningirsu became ensi. Then, his son Lugalanda suceeded him, but was soon deprived of his political power by Uruinimgina. The economic-administrative archives(1) of Lagas which are the most important historical materials for the history of the Sumerian society were written during a period of about twenty years from Enentarzi to Urui- nimgina, and a greater part of those belong to the organization called e-mi (the house of the wife (of the ruler)). Among those, there exist many texts called nig-gis-tag-ga texts,(2) which record offerings to deities, temples and so on mainly on festivals. In those we can find that statues of Entemena and others receive offerings. I will attempt to discuss the meaning of offerings to these statues, especially that of Entemena in this article. II. The statues in nig-gis-tag-ga texts 1. nig-gis-tag-ga texts These are detailed account books of the kind and the quantity of offerings which a ruler or his wife gave to deities, temples and so on. We find a brief and compact summarization of the content at the end of the text, such as follows: DP 53, XIX, 1) ezem-munu4-ku- 2) dnanse-ka 3) bar-nam-tar-ra 4) dam-lugal- an-da 5) ensi- 6) lagaski-ka-ke4 7) gis be-tag(3) III "At the festival of eating malt of Nanse, Barnamtarra, wife of Lugalanda, ensi of Lagas, made the sacrifice (of them)." Though the agent who made the sacrifice in the texts is almost always a wife of a ruler, there remain four texts, BIN 8, 371; Nik. -

" King of Kish" in Pre-Sarogonic Sumer

"KING OF KISH" IN PRE-SAROGONIC SUMER* TOHRU MAEDA Waseda University 1 The title "king of Kish (lugal-kiski)," which was held by Sumerian rulers, seems to be regarded as holding hegemony over Sumer and Akkad. W. W. Hallo said, "There is, moreover, some evidence that at the very beginning of dynastic times, lower Mesopotamia did enjoy a measure of unity under the hegemony of Kish," and "long after Kish had ceased to be the seat of kingship, the title was employed to express hegemony over Sumer and Akked and ulti- mately came to signify or symbolize imperial, even universal, dominion."(1) I. J. Gelb held similar views.(2) The problem in question is divided into two points: 1) the hegemony of the city of Kish in early times, 2) the title "king of Kish" held by Sumerian rulers in later times. Even earlier, T. Jacobsen had largely expressed the same opinion, although his opinion differed in some detail from Hallo's.(3) Hallo described Kish's hegemony as the authority which maintained harmony between the cities of Sumer and Akkad in the First Early Dynastic period ("the Golden Age"). On the other hand, Jacobsen advocated that it was the kingship of Kish that brought about the breakdown of the older "primitive democracy" in the First Early Dynastic period and lead to the new pattern of rule, "primitive monarchy." Hallo seems to suggest that the Early Dynastic I period was not the period of a primitive community in which the "primitive democracy" was realized, but was the period of class society in which kingship or political power had already been formed. -

Saxon Shield Wall Home Learners Pack

Suitable for ages 7-11 KS2 History KS2 English KS2 Art & Design Saxon Shield Wall The Saxons lived in Britain from around 450AD to 1066 when they were over taken by the Normans. The Saxons were fierce warriors and fought in many ferocious battles, against both Vikings and Normans. Their warriors had lots of weapons, such as axes, swords, spears and knives. But they also had protection in the form of helmets, armour and shields. They were in fact famous for using their shields very well, by creating a shield wall. Read on to learn more about Saxon battle tactics. Additional resources Watch a video all about Saxon shield walls on our YouTube channel. Saxon Shield Wall / © Royal Armouries / April 2020 / 1/4 Fascinating Facts How do you make a shield wall? A shield wall is a military tactic. Soldiers line up, shoulder to shoulder and hold their shields in front of them. They stand so close together that their shields overlap. This means that they are protected by their own shield, and by the shields held by the soldiers on either side of them. Image courtesy of Bayeux Museum Types of shield Can you see? The Saxons used 2 different If you look closely at the image you can styles of shield. see that part of the shield wall is The most common type was round. together but there are also a few gaps. They were called ‘trelborg’ shields. What do you think the enemy might do The other type was kite-shaped like the if they saw a gap in the shield wall? ones in the image. -

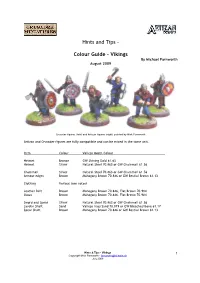

Hints and Tips

Hints and Tips - Colour Guide – Vikings By Michael Farnworth August 2009 Crusader figures (left) and Artizan figures (right) painted by Mick Farnworth Artizan and Crusader figures are fully compatible and can be mixed in the same unit. Item Colour Vallejo Model Colour Helmet Bronze GW Shining Gold 61.63 Helmet Silver Natural Steel 70.863 or GW Chainmail 61.56 Chainmail Silver Natural Steel 70.863 or GW Chainmail 61.56 Armour edges Brown Mahogany Brown 70.846 or GW Bestial Brown 61.13 Clothing Various (see notes) Leather Belt Brown Mahogany Brown 70.846, Flat Brown 70.984 Shoes Brown Mahogany Brown 70.846, Flat Brown 70.984 Sword and Spear Silver Natural Steel 70.863 or GW Chainmail 61.56 Javelin Shaft Sand Vallejo Iraqi Sand 70.819 or GW Bleached Bone 61.17 Spear Shaft Brown Mahogany Brown 70.846 or GW Bestial Brown 61.13 Hints & Tips - Vikings 1 Copyright Mick Farnworth - [email protected] July 2009 Introduction This guide will help you to quickly paint units of Vikings to look good on a war games table. Historical notes, paint references and painting tips are included. Historical Notes Vikings were warriors originating from Scandinavia. The word Viking has many interpretations ranging from voyager to explorer to pirate. Vikings travelled far and wide reaching Greenland and America in the West and Russia and Byzantium in the East. The Viking Age is regarded as starting with raids on Lindisfarne in 789 and ending with the Battle of Stamford Bridge in 1066. Throughout the 9 th and 10 th Centuries Vikings raided England, Ireland, France and Spain. -

The Arms and Armour of 1066

Suitable for ages 11-16 KS3 & KS4 History KS3 & KS4 English The Arms and Armour of 1066 The year 1066 is famous for changing the course of English history. The death of Edward I, also known as Edward the Confessor, caused a succession crisis. Three contenders would fight for the English crown and the right to rule the country. ° Harold Godwinson of Saxon England ° Harald Hardrada of Norway ° William the Duke of Normandy All three believed they had a right to the English throne. In order to fight for the crown they needed armies with weapons, armour and battle tactics. The ensuing epic battles of Fulford, Stamford Bridge and Hastings have earned their place in the history books, and led to William Duke of Normandy becoming King of England. Let’s focus on the Battle of Hastings and have a look at the weapons and armour the warriors used nearly 1,000 years ago. Additional resources Watch a video all about the arms and armour of 1066 on our YouTube channel. Arms & Armour of 1066 / © Royal Armouries / April 2020 / 1/5 The Saxons Axes Types of Saxon warriors Axes were a very common weapon in Europe at that time. Saxon Housecarls are often depicted armed with axes on the Bayeux Tapestry, and the Viking warriors of Hardrada’s army would certainly have wielded them too. This axe head, from our collection, is possibly of Viking origin. These weapons caused a huge amount of damage and injury. The axe head would be mounted on a long handle, between 1.5 and 2 metres in length. -

The Calontir Army Songbook

Under the Shield Wall Words: Chidiock the Younger and Andrixos Seljukroctonis Music: Under the Boardwalk Oh when the sun is hot and your head's burning in your helm, The And though you fight and fight, neither side can overwhelm. Under the shield wall, it's the place to be, With my lady beside me, willingly. (Completely Unofficial) Under the shield wall, where it's quiet and dark, Under the shield wall, like our own private park, Under the shield wall, polearms crashing above, Under the shield wall, we'll be making love, Under the slieldwan, shield wall. Calontir Army Oh it's the sales! place !hal fighter can ever be. No weapon reaches there to break our sweet tranquility, Under the shield wall, out of the sun, Fighters" Authorization With my lady beside me, we'll be havin' fun. • Chorus So when the sides are joined, and you find yourself in the press, Why don't you join me there and take a break from battle strass. Under the shield wall, it's the place to be, With my lady beside me, carnally. Chorus CHOIR A Grazing Mace, I Men of Hartech, I2 Bocephus Song, I7 Navy of Calontir, I2 Calontir Stands Alone, I Non Nobis, 13 Songbook Cheer, 2 None but Calontir-0, 13 Cruiskeen Lawn, 3 Pavel's Song, I4 Drums in my Heart, 4 Ques~ I4 For Crown and For Kingdom, S Raven Banner, IS Fyrdmen on Campaign, 6 Requiem for A Huscart, I6 \ Hal's Song (The man o'war), 4 Song of the Caton Huscart, IS Hamster Song, 7 Song of the Shield Wall, I7 Hit 'em Again, 8 Steel-Shod Dance, I8 Hotspur, 9 Under the Shield Wall, 19 Knighfs Leap, 10 We Be Soldiers Three, 7 Leaving Song, II P ennsic XXX edition 19 A Grazing Mace Cheer Words: Fernando Rodriguez de Falcon and Lyriel de Ia Foret A grazing mace, how sweet the blow That mace has slain ten thousand foes Tune: Bird of Prey March Leslie Rsh That killed a wretch like me. -

Sargon of Akkad: Rebel and Usurper in Kish

Chapter 3 Sargon of Akkad: Rebel and Usurper in Kish Marlies Heinz When Sargon of Akkad (ca. 2340–2280 b.c.) seized power in Kish, it was the begin- ning of a reign that would restructure the entire political landscape of the Near East. Legend has it that Sargon was the son of a high-ranking priestess who immediately after his birth placed him in a basket and abandoned him to the Euphrates.1 A man named Aqqi discovered the baby, pulled him out of the river, and adopted him. Sar- gon became a gardener at his father’s estate. It is not known in detail how he ended up at the royal court in Kish. Traditionally it is believed that he was taken there by the town goddess, Ishtar, who had seen him in his father’s garden. Sargon did not belong to the traditional elite of Kish; he did not know anything about his origins. At court he became the king’s cupbearer. From this position, he re- belled against the authorities and deprived the legitimate (!) king, Urzababa, of his power with the approval of, and by the will of, the deities An, Enlil, and Ishtar. Sargon became Urzababa’s successor and sealed his accession to the throne by taking the title Sharru-kin (= Sargon), which means ‘the legitimate king’. At the beginning of his reign, Sargon changed most of the traditional political structure of Kish. The “old ones” (intimates of the former king?) and the temple priests were deprived of their power, and the palace took over the economic domains of the temples. -

Summer and Akkad Geographical Context the Fertile Crescent Ubaid Culture

Summer and Akkad Geographical Context The Fertile Crescent Ubaid Culture • Roughly 6000 – 3500 BC. • First pottery • First settled ‘towns’ • “The creators of the Ubaid… were heirs to cumulative developments in the long history of agricultural village life in the Near East” (Hout 1992, 188). Sumerians Arrived from Asia ca 3900 – 3500 Unique language that resembles Turkic and Hungarian • Brought (?) Copper tech. • Applied to irrigation • Kish or Uruk earliest city • Competing city states • Legend of the Flood • Legends of divine parentage Sumer Kuhrt • Kuhrt, Amelie. 1995. The Ancient Near East. • Cultural parallelism • Semitic words in Sumerian texts • Diversity of land ownership • Monarchy more than theocracy • Contra Edgar et al. City Rivalries • Eannatum, king of Lagash • Ca. 2450 BC • Conquered the cities of Sumer • Vulture Stele commemorates victory over Enakalle of Umma The Vulture Stele The Vulture Stele • Winter, Irene. 1985. After the Battle is Over: The “Stele of the Vultures” and the Beninning of Historical Narrative in the Art of the Ancient Near East. Studies in the History of Art 16, Symposium Papers IV: Pictoral Narrative in Antiquity and the Middle Ages: 11 – 32. Sargon of Akkad (Agade) • Lugalzagesi • Ruler of Uruk • Hegemon of Sumerian empire • Sargon • Ruler of Akkad (2296 - 2240) • Semitic • Begins a literary tradition of pasts remembered (recreated). The Dynasty of Sargon • Sargon (2296 -2240) • Rimush (2239 – 2230) • Manishtushu (2229 – 2214) • Naram Sin (2213 – 2176) • Sharkalisharri (2175 – 2150) • …but these dates are disputed Ur – The Sumerian Renaissence • Utuhegal (2119 – 2113) • Ur-Nammu (2112 – 2095) • Shulgi (2094 – 2047) • Amar –Sin (2046 – 2038) • Shu-Sin (2037 – 2027) • Ibbi-Sin (2026 – 2004) Material Record Cylinder Seals Cuneiform Bronze • Ca. -

Historical Evolution of Roman Infantry Arms And

HISTORICAL EVOLUTION OF ROMAN INFANTRY ARMS AND ARMOR 753 BC - 476 AD An Interactive Qualifying Project Report Submitted to the Faculty of the WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE In partial fulfillment to the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Science By Evan Bossio Robert Chase Justin Dyer Stephanie Huang Marmik Patel Nathan Siegel Date: March 2, 2018 Submitted to: Professor Diana A. Lados Professor Luca Capogna Abstract During its time, the Roman Empire gained a formidable reputation as a result of its discipline and organization. The Roman Empire has made a lasting impact on the world due to its culture, political structure, and military might. The purpose of this project was to examine how the materials and processes used to create the weapons and armour helped to contribute to the rise and fall of the Roman Empire. This was done by analyzing how the Empire was able to successfully integrate new technologies and strategies from the regions the Empire conquered. The focus of this project is on the Empire's military, including the organization of the army, and the tactics and weapons used. To better understand the technology and innovations during this time the Roman long sword, spatha, was replicated and analyzed. 1 Acknowledgments The team would like to thank Professor Diana A. Lados and Professor Luca Capogna for this unique experience. The team would also like to thank Anthony Spangenberger for his guidance and time throughout the microstructure analysis. Lastly, this project could not have been done without Joshua Swalec, who offered his workshop, tools, and expertise throughout the manufacturing process 2 Table of Contents Abstract 1 Acknowledgments 2 Table of Contents 3 List of Figures 6 List of Tables 11 Authorship 12 1.