Was There a Clinton Doctrine? President Clinton's Foreign Policy Reconsidered

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Regime Change Consensus: Iraq in American Politics, 1990-2003

THE REGIME CHANGE CONSENSUS: IRAQ IN AMERICAN POLITICS, 1990-2003 Joseph Stieb A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in the College of Arts and Sciences. Chapel Hill 2019 Approved by: Wayne Lee Michael Morgan Benjamin Waterhouse Daniel Bolger Hal Brands ©2019 Joseph David Stieb ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Joseph David Stieb: The Regime Change Consensus: Iraq in American Politics, 1990-2003 (Under the direction of Wayne Lee) This study examines the containment policy that the United States and its allies imposed on Iraq after the 1991 Gulf War and argues for a new understanding of why the United States invaded Iraq in 2003. At the core of this story is a political puzzle: Why did a largely successful policy that mostly stripped Iraq of its unconventional weapons lose support in American politics to the point that the policy itself became less effective? I argue that, within intellectual and policymaking circles, a claim steadily emerged that the only solution to the Iraqi threat was regime change and democratization. While this “regime change consensus” was not part of the original containment policy, a cohort of intellectuals and policymakers assembled political support for the idea that Saddam’s personality and the totalitarian nature of the Baathist regime made Iraq uniquely immune to “management” strategies like containment. The entrenchment of this consensus before 9/11 helps explain why so many politicians, policymakers, and intellectuals rejected containment after 9/11 and embraced regime change and invasion. -

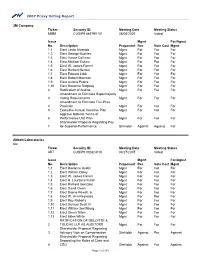

2007 Proxy Voting Report 3M Company Ticker Security ID: MMM

2007 Proxy Voting Report 3M Company Ticker Security ID: Meeting Date Meeting Status MMM CUSIP9 88579Y101 05/08/2007 Voted Issue Mgmt For/Agnst No. Description Proponent Rec Vote Cast Mgmt 1.1 Elect Linda Alvarado Mgmt For For For 1.2 Elect George Buckley Mgmt For For For 1.3 Elect Vance Coffman Mgmt For For For 1.4 Elect Michael Eskew Mgmt For For For 1.5 Elect W. James Farrell Mgmt For For For 1.6 Elect Herbert Henkel Mgmt For For For 1.7 Elect Edward Liddy Mgmt For For For 1.8 Elect Robert Morrison Mgmt For For For 1.9 Elect Aulana Peters Mgmt For For For 1.10 Elect Rozanne Ridgway Mgmt For For For 2 Ratification of Auditor Mgmt For For For Amendment to Eliminate Supermajority 3 Voting Requirements Mgmt For For For Amendment to Eliminate Fair-Price 4 Provision Mgmt For For For 5 Executive Annual Incentive Plan Mgmt For For For Approve Material Terms of 6 Performance Unit Plan Mgmt For For For Shareholder Proposal Regarding Pay- 7 for-Superior-Performance ShrHoldr Against Against For Abbott Laboratories Inc Ticker Security ID: Meeting Date Meeting Status ABT CUSIP9 002824100 04/27/2007 Voted Issue Mgmt For/Agnst No. Description Proponent Rec Vote Cast Mgmt 1.1 Elect Roxanne Austin Mgmt For For For 1.2 Elect William Daley Mgmt For For For 1.3 Elect W. James Farrell Mgmt For For For 1.4 Elect H. Laurance Fuller Mgmt For For For 1.5 Elect Richard Gonzalez Mgmt For For For 1.6 Elect David Owen Mgmt For For For 1.7 Elect Boone Powell, Jr. -

Democratic Vanguardism

Democratic Vanguardism Modernity, Intervention, and the making of the Bush Doctrine Michael Harland A Thesis Submitted in Fulfillment of The Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Department of History University of Canterbury 2013 For Francine Contents Acknowledgements 1 Abstract 3 Introduction 4 1. America at the Vanguard: Democracy Promotion and the Bush Doctrine 16 2. Assessing History’s End: Thymos and the Post-Historic Life 37 3. The Exceptional Nation: Power, Principle and American Foreign Policy 55 4. The “Crisis” of Liberal Modernity: Neoconservatism, Relativism and Republican Virtue 84 5. An “Intoxicating Moment:” The Rise of Democratic Globalism 123 6. The Perfect Storm: September 11 and the coming of the Bush Doctrine 159 Conclusion 199 Bibliography 221 1 Acknowledgements Over the three years I spent researching and writing this thesis, I have received valuable advice and support from a number of individuals and organisations. My supervisors, Peter Field and Jeremy Moses, were exemplary. As my senior supervisor, Peter provided a model of a consummate historian – lively, probing, and passionate about the past. His detailed reading of my work helped to hone the thesis significantly. Peter also allowed me to use his office while he was on sabbatical in 2009. With a library of over six hundred books, the space proved of great use to an aspiring scholar. Jeremy Moses, meanwhile, served as the co-supervisor for this thesis. His research on the connections between liberal internationalist theory and armed intervention provided much stimulus for this study. Our discussions on the present trajectory of American foreign policy reminded me of the continuing pertinence of my dissertation topic. -

Madeleine Albright, Gender, and Foreign Policy-Making

Journal of Political Science Volume 33 Number 1 Article 2 November 2005 Madeleine Albright, Gender, and Foreign Policy-Making Kevin J. Lasher Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.coastal.edu/jops Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Lasher, Kevin J. (2005) "Madeleine Albright, Gender, and Foreign Policy-Making," Journal of Political Science: Vol. 33 : No. 1 , Article 2. Available at: https://digitalcommons.coastal.edu/jops/vol33/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Politics at CCU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Political Science by an authorized editor of CCU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Madeleine Albright , Gender, and Foreign Policy-Making Kevin J. Lashe r Francis Marion University Women are finally becoming major participants in the U.S. foreign policy-making establishment . I seek to un derstand how th e arrival of women foreign policy-makers might influence the outcome of U.S. foreign polic y by fo cusi ng 011 th e activities of Mad elei n e A !bright , the first wo man to hold the position of Secretary of State . I con clude that A !bright 's gender did hav e some modest im pact. Gender helped Albright gain her position , it affected the manner in which she carried out her duties , and it facilitated her working relationship with a Repub lican Congress. But A !bright 's gender seemed to have had relatively little effect on her ideology and policy recom mendations . ver the past few decades more and more women have won election to public office and obtained high-level Oappointive positions in government, and this trend is likely to continue well into the 21st century. -

Iraq: Differing Views in the Domestic Policy Debate

Order Code RL31607 Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web Iraq: Differing Views in the Domestic Policy Debate October 16, 2002 name redacted, Meaghan Marshall, name redacted Research Associates Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division name redacted Specialist in National Defense Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Congressional Research Service ˜ The Library of Congress Iraq: Differing Views in the Domestic Policy Debate Summary The debate over whether, when, and how to prosecute a major U.S. military intervention in Iraq and depose Saddam Hussein is complex, despite a general consensus in Washington that the world would be much better off if Hussein were not in power. Although most U.S. observers, for a variety of reasons, would prefer some degree of allied or U.N. support for military intervention in Iraq, some observers believe that the United States should act unilaterally even without such multilateral support. Some commentators argue for a stronger, more committed version of the current policy approach toward Iraq and leave war as a decision to reach later, only after exhausting additional means of dealing with Hussein’s regime. A number of key questions are raised in this debate, such as: 1) is war on Iraq linked to the war on terrorism and to the Arab-Israeli dispute; 2) what effect will a war against Iraq have on the war against terrorism; 3) are there unintended consequences of warfare, especially in this region of the world; 4) what is the long- term political and financial commitment likely to accompany regime change and possible democratization in this highly divided, ethnically diverse country; 5) what are the international consequences (e.g., to European allies, Russia, and the world community) of any U.S. -

World Powers Rivalry in Afghanistan and Its Effects on Pakistan Muhammad Karim

World Powers Rivalry in Afghanistan and Its Effects on Pakistan Muhammad Karim Abstract Afghanistan, a landlocked country, has been the focus of great powers since 19 th century due to its strategic locations. Soviet Union and Great Briton were engaged in Afghanistan before the World Wars. After Soviet Union invasion of Afghanistan in 1979, the U.S. led West with the support of Muslim countries compelled the Red Army to withdraw in 1988. The country became a battle field of proxy wars among the regional and extra regional powers, creating instability in entire region. In aftermath of the 9/11, Afghanistan once again attracted attention of the world powers. Nature and complexity of Great Powers’ rivalry in Afghanistan has changed overtime. Instead of fighting against a nation state the world powers are fighting against the potential threats of extremism, terrorism and drug trafficking that makes the war more complicated, problematic and challenging. Currently, apart from Al-Qaeda and Taliban, Islamic State (IS) is also becoming an active stakeholder in Afghanistan. These developments make the Afghan problem more complicated and ripening the grounds for another civil war. The study argues that since Pakistan not only shares long borders but also history, culture, interests, happiness and sorrows with Afghanistan, therefore situation in Afghanistan always have direct bearing on the security matrix of Pakistan. US and NATO forces withdrawal from Afghanistan has provided an open field to Al-Qaeda/Taliban and IS in one hand and encourage regional and international players on another, creating security dilemma for Pakistan. Keywords: World powers rivalry, Afghan war, Al-Qaeda, Taliban, Islamic State (IS), Pakistan. -

Hearings on the Nomination of Hon. Rich- Ard C. Holbrooke to Serve As Us Ambas

S. HRG. 106±225 HEARINGS ON THE NOMINATION OF HON. RICH- ARD C. HOLBROOKE TO SERVE AS U.S. AMBAS- SADOR TO THE UNITED NATIONS HEARINGS BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN RELATIONS UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED SIXTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION JUNE 17, 22, AND 24, 1999 Printed for the use of the Committee on Foreign Relations ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.access.gpo.gov/congress/senate U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 57±735 CC WASHINGTON : 1999 COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN RELATIONS JESSE HELMS, North Carolina, Chairman RICHARD G. LUGAR, Indiana JOSEPH R. BIDEN, JR., Delaware PAUL COVERDELL, Georgia PAUL S. SARBANES, Maryland CHUCK HAGEL, Nebraska CHRISTOPHER J. DODD, Connecticut GORDON H. SMITH, Oregon JOHN F. KERRY, Massachusetts ROD GRAMS, Minnesota RUSSELL D. FEINGOLD, Wisconsin SAM BROWNBACK, Kansas PAUL D. WELLSTONE, Minnesota CRAIG THOMAS, Wyoming BARBARA BOXER, California JOHN ASHCROFT, Missouri ROBERT G. TORRICELLI, New Jersey BILL FRIST, Tennessee STEPHEN E. BIEGUN, Staff Director EDWIN K. HALL, Minority Staff Director (II) CONTENTS THURSDAY, JUNE 17, 1999 Page Biden, Joseph R., Jr., U.S. Senator from Delaware, opening statement ............ 4 Boxer, Barbara, U.S. Senator from California, prepared statement of ............... 34 Helms, Jesse, U.S. Senator from North Carolina, opening statement ................ 1 Holbrooke, Hon. Richard C., nominee to be U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations .................................................................................................................. 10 Prepared statement of ...................................................................................... 16 Moynihan, Daniel Patrick, U.S. Senator from New York, statement ................. 9 Warner, John W., U.S. Senator from Virginia, statement ................................... 7 TUESDAY, JUNE 22, 1999 Biden, Joseph R., Jr., U.S. Senator from Delaware, opening statement ............ 47 Helms, Jesse, U.S. -

Jimmy Carter: a Moral Hero (Student Essay)

Jimmy Carter: A Moral Hero (Student Essay) Danny Haidar (Utica Academy for International Studies) Abstract. Following the end of Jimmy Carter’s first and only term as President of the United States, historians scrambled to put his presidency in the proper context. More than thirty years later, Carter has become associated with failed presidencies. To be compared to him is to be insulted. Even so, Jimmy Carter has had one of the most prolific, philanthropic post-presidential lives of any former American president. This is inconsistent with the image of his single term in office that the media has painted—a good man should have been a good president. To better understand this irony, this investigation shall seek to answer the following question: how did Jimmy Carter’s pre-presidential experiences affect his leadership as President of the United States of America (1977-1981)? This article will draw on apolitical, supportive and critical accounts of Carter’s presidency, as well as Carter’s own accounts of his beliefs and childhood experiences. While historians interpret Carter’s life events differently, each interpretation reveals important influences on Carter’s leadership in the White House. I will argue that Carter held too tightly to his morals to be suited to presidency. Carter’s childhood and pre-presidential political experiences created a man who was, indeed, unfit for the White House. The problem was less with his political vision than it was with his execution of that vision. Carter’s tragic presidential tale serves as a reminder that moral malleability is a necessity in the highest office of a government. -

Power Projection and Force Deployment Under Reagan

Chapman University Chapman University Digital Commons War and Society (MA) Theses Dissertations and Theses Fall 12-20-2019 The Ladle and the Knife: Power Projection and Force Deployment under Reagan Mathew Kawecki Chapman University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/war_and_society_theses Part of the Political History Commons Recommended Citation Kawecki, Mathew. The Ladle and the Knife: Power Projection and Force Deployment under Reagan. 2019. Chapman University, MA Thesis. Chapman University Digital Commons, https://doi.org/10.36837/ chapman.000095 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at Chapman University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in War and Society (MA) Theses by an authorized administrator of Chapman University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Ladle and the Knife: Power Projection and Force Deployment under Reagan A Thesis by Mathew D. Kawecki Chapman University Orange, CA Wilkinson College of Arts, Humanities, and Social Sciences Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in War and Society Studies December 2019 Committee in charge: Gregory Daddis, Ph.D., Chair Robert Slayton, Ph.D. Alexander Bay, Ph.D. The thesis ofMathew D. Kawecki is approved. Ph.D., Chair Eabert Slalton" Pir.D AlexanderBa_y. Ph.D September 2019 The Ladle and the Knife: Power Projection and Force Deployment under Reagan Copyright © 2019 by Mathew D. Kawecki III ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my advisor, Dr. Greg Daddis, for his academic mentorship throughout the thesis writing process. -

Remembering World War Ii in the Late 1990S

REMEMBERING WORLD WAR II IN THE LATE 1990S: A CASE OF PROSTHETIC MEMORY By JONATHAN MONROE BULLINGER A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-New Brunswick Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in Communication, Information, and Library Studies Written under the direction of Dr. Susan Keith and approved by Dr. Melissa Aronczyk ________________________________________ Dr. Jack Bratich _____________________________________________ Dr. Susan Keith ______________________________________________ Dr. Yael Zerubavel ___________________________________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey January 2017 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Remembering World War II in the Late 1990s: A Case of Prosthetic Memory JONATHAN MONROE BULLINGER Dissertation Director: Dr. Susan Keith This dissertation analyzes the late 1990s US remembrance of World War II utilizing Alison Landsberg’s (2004) concept of prosthetic memory. Building upon previous scholarship regarding World War II and memory (Beidler, 1998; Wood, 2006; Bodnar, 2010; Ramsay, 2015), this dissertation analyzes key works including Saving Private Ryan (1998), The Greatest Generation (1998), The Thin Red Line (1998), Medal of Honor (1999), Band of Brothers (2001), Call of Duty (2003), and The Pacific (2010) in order to better understand the version of World War II promulgated by Stephen E. Ambrose, Tom Brokaw, Steven Spielberg, and Tom Hanks. Arguing that this time period and its World War II representations -

Won't You Be My Neighbor

Won’t You Be My Neighbor: Syria, Iraq and the Changing Strategic Context in the Middle East S TEVEN SIMON Council on Foreign Relations March 2009 www.usip.org Date www.usip.org UNITED STATES INSTITUTE OF PEACE – WORKING PAPER Won’t You Be My Neighbor UNITED STATES INSTITUTE OF PEACE 1200 17th Street NW, Suite 200 Washington, DC 20036-3011 © 2009 by the United States Institute of Peace. The views expressed in this report do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Institute of Peace, which does not advocate specific policy positions. This is a working draft. Comments, questions, and permission to cite should be directed to the author ([email protected]) or [email protected]. This is a working draft. Comments, questions, and permission to cite should be directed to the author ([email protected]) or [email protected]. UNITED STATES INSTITUTE OF PEACE – WORKING PAPER Won’t You Be My Neighbor About this Report Iraq's neighbors are playing a major role—both positive and negative—in the stabilization and reconstruction of post-Saddam Iraq. In an effort to prevent conflict across Iraq's borders and in order to promote positive international and regional engagement, USIP has initiated high-level, non-official dialogue between foreign policy and national security figures from Iraq, its neighbors and the United States. The Institute’s "Iraq and its Neighbors" project has also convened a group of leading specialists on the geopolitics of the region to assess the interests and influence of the countries surrounding Iraq and to explain the impact of these transformed relationships on U.S. -

Monroe Doctrine Over Time from Kevin Grant Grade - 8

TEACHING AMERICAN HISTORY PROJECT Lesson Title – The Monroe Doctrine Over Time From Kevin Grant Grade - 8 Length of class period – 50 Inquiry – (What essential question are students answering, what problem are they solving, or what decision are they making?) How do US policies evolve? Objectives (What content and skills do you expect students to learn from this lesson?) Students will summarize reading content. Students will compare and contrast US police over time. Students will support their position with evidence from resources. Materials (What primary sources or local resources are the basis for this lesson?) – (please attach) Monroe Doctrine http://avalon.law.yale.edu/19th_century/monroe.asp Monroe Doctrine Summary http://history1800s.about.com/od/1800sglossary/g/monroedocdef.htm Roosevelt Corollary http://www.pinzler.com/ushistory/corollarysupp.html Roosevelt Corollary Summary http://www.ushistory.org/us/44e.asp Truman Doctrine http://www.ourdocuments.gov/doc.php?flash=true&doc=81 Clinton Doctrine http://www.thenation.com/article/clinton-doctrine “From Wounded Knee To Libya: A Century of U.S. Military Interventions,” by Dr. Zoltan Grossman http://academic.evergreen.edu/g/grossmaz/interventions.html Monroe Doctrine Activity Sheet (attached) Activities (What will you and your students do during the lesson to promote learning?) 1. Distribute copies of one policy to each group along with Monroe Doctrine Activity Sheet, and Copies of “From Wounded Knee to Libya…” have students work as a group to summarize their assigned policy. Question 1 2. Have students share their summary of each Doctrine (teacher should clarify for whole class if needed), and record policy on organizer. 3.