Remembering World War Ii in the Late 1990S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Original Band of Brothers Tour Walk in the Footsteps of the Men of Easy Company 2015 Band of Brothers Tours Are Sold Out

Stephen Ambrose Historical Tours presents The Original Band Of BrOThers TOur Walk in The Footsteps of The Men of Easy Company 2015 Band of Brothers tours are sold out. 2016 dates to be announced soon. Day 1 Arrival in Atlanta The tour begins in Atlanta with an informal Welcome Reception where participants will have an opportunity to get acquainted with each other and meet the historians and tour staff. A brief overview of the legacy of Easy Company will set the stage for the days ahead. Day 2 Toccoa: Birthplace of the 506th Ask any of the original members of Easy Company what made the unit so special and they will answer: “Toccoa.” This training ground in the north Georgia woods was where the bonding process of the 506th began. As it did for so many of the men of Easy Company, our tour of Toccoa will begin at the train station where recruits for the 506th first arrived. The station also houses the Stephens County Historical Immortalized by the Stephen Ambrose best-seller, “Band of Society, the 506th Museum and the unique collection of Brothers,” and brought to millions more in the epic Steven artifacts and memorabilia from Camp Toccoa. Following Spielberg/Tom Hanks HBO miniseries of the same name, the men of Easy Company were on an extraordinary journey lunch, we travel to the site of the Camp and then during WWII. From D-Day to V-E Day, the paratroopers of E proceed up Mount Currahee, the 1,000 foot mountain Company, 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment participated in the men of the 506th ran daily for training. -

Dublin City Council City Dublin 2018 ©

© 2018 Dublin City Council City Dublin 2018 © This Map & Guide was produced by Dublin City Council in partnership with Portobello Residents Group. Special thanks to Ciarán Breathnach for research and content. Thanks also to the following for their contribution to the Portobello Walking Trail: Anthony Freeman, Joanne Freeman, Pat Liddy, Canice McKee, Fiona Hayes, Historical Picture Archive, National Library of Ireland and Dublin City Library & Archive. Photographs by Joanne Freeman and Drew Cooke. For further reading on Portobello: ‘Portobello’ by Maurice Curtis and ‘Jewish Dublin: Portraits of Life by the Liffey’ by Asher Benson. For details on Dublin City Council’s programme of walking tours and weekly walking groups, log on to www.letswalkandtalk.ie For details on Pat Liddy’s Walking Tours of Dublin, log on to www.walkingtours.ie For details on Portobello Residents Group, log on to www.facebook.com/portobellodublinireland Design & Production: Kaelleon Design (01 835 3881 / www.kaelleon.ie) Portobello derives its name from a naval battle between Great Britain and Welcome to Portobello! This walking trail emigrated, the building fell into disuse and ceased functioning as a place of worship by Spain in 1739 when the settlement of Portobello on Panama’s Carribean takes you through “Little Jerusalem”, along the mid 1970s. The museum exhibits a large collection of memorabilia and educational displays relating to the Irish Jewish communities. Close by at 1 Walworth Road is the the Grand Canal and past the homes of many The original bridge over the Grand Canal was built in 1790. In 1936 it was rebuilt and coast was captured by the British. -

Las Aportaciones Al Cine De Steven Spielberg Son Múltiples, Pero Sobresale Como Director Y Como Productor

Steven Spielberg Las aportaciones al cine de Steven Spielberg son múltiples, pero sobresale como director y como productor. La labor de un productor de cine puede conllevar cierto control sobre las diversas atribuciones de una película, pero a menudo es poco más que aportar el dinero y los medios que la hacen posible sin entrar mucho en los aspectos creativos de la misma como el guión o la dirección. Es por este motivo que no me voy a detener en la tarea de Spielberg como productor más allá de señalar sus dos productoras de cine y algunas de sus producciones o coproducciones a modo de ejemplo, para complementar el vistazo a la enorme influencia de Spielberg en el mundo cinematográfico: En 1981 creó la productora de cine “Amblin Entertainment” junto con Kathleen Kenndy y Frank Marshall. El logo de esta productora pasaría a ser la famosa silueta de la bicicleta con luna llena de fondo de “ET”, la primera producción de la firma dirigida por Spielberg. Otras películas destacadas con participación de esta productora y no dirigidas por Spielberg son “Gremlins”, “Los Goonies”, “Regreso al futuro”, “Esta casa es una ruina”, “Fievel y el nuevo mundo”, “¿Quién engañó a Roger Rabbit?”, “En busca del Valle Encantado”, “Los picapiedra”, “Casper”, “Men in balck”, “Banderas de nuestros padres” & “Cartas desde Iwo Jima” o las series de televisión “Cuentos asombrosos” y “Urgencias” entre muchas otras películas y series. En 1994 fundaría con Jeffrey Katzenberg y David Geffen la productora y distribuidora DreamWorks, que venderían al estudio Viacom en 2006 tras participar en éxitos como “Shrek”, “American Beauty”, “Náufrago”, “Gladiator” o “Una mente maravillosa”. -

Annie Stone, 703-217-1169 Jonathan Thompson, 202-821-8926 [email protected] [email protected]

Contact: Annie Stone, 703-217-1169 Jonathan Thompson, 202-821-8926 [email protected] [email protected] NATIONAL CONSTITUTION CENTER TO DISPLAY 50-TON FIRST AMENDMENT TABLET FROM NEWSEUM FACADE Pennsylvania Avenue’s iconic First Amendment stone tablet finds new home on Independence Mall in Philadelphia Philadelphia, PA (March 18, 2021) – The National Constitution Center announced it will be the new home for the iconic First Amendment tablet from the former Newseum building in Washington, D.C. The 50-ton marble tablet, engraved with the 45 words of the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, was displayed on the four-story-high, 74-foot-tall Pennsylvania Avenue façade of the Newseum, a nonprofit museum founded by the Freedom Forum and dedicated to the five freedoms of the First Amendment. Work has begun to remove the stone pieces from the building, which was sold to Johns Hopkins University after the Newseum closed in 2019. The tablet remained the property of the Freedom Forum, and will be a gift to the National Constitution Center. The tablet will be reconfigured and emplaced along a 100-foot-wide wall on the National Constitution Center’s Grand Hall Overlook, the second-floor atrium overlooking historic Independence Mall. “We are thrilled to bring this heroic marble tablet of the First Amendment to the National Constitution Center, to inspire visitors from across America and around the world for generations to come,” said National Constitution Center President and CEO Jeffrey Rosen. “It’s so meaningful to bring -

What Do Students Know and Understand About the Holocaust? Evidence from English Secondary Schools

CENTRE FOR HOLOCAUST EDUCATION What do students know and understand about the Holocaust? Evidence from English secondary schools Stuart Foster, Alice Pettigrew, Andy Pearce, Rebecca Hale Centre for Holocaust Education Centre Adrian Burgess, Paul Salmons, Ruth-Anne Lenga Centre for Holocaust Education What do students know and understand about the Holocaust? What do students know and understand about the Holocaust? Evidence from English secondary schools Cover image: Photo by Olivia Hemingway, 2014 What do students know and understand about the Holocaust? Evidence from English secondary schools Stuart Foster Alice Pettigrew Andy Pearce Rebecca Hale Adrian Burgess Paul Salmons Ruth-Anne Lenga ISBN: 978-0-9933711-0-3 [email protected] British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A CIP record is available from the British Library All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purposes of criticism or review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permissions of the publisher. iii Contents About the UCL Centre for Holocaust Education iv Acknowledgements and authorship iv Glossary v Foreword by Sir Peter Bazalgette vi Foreword by Professor Yehuda Bauer viii Executive summary 1 Part I Introductions 5 1. Introduction 7 2. Methodology 23 Part II Conceptions and encounters 35 3. Collective conceptions of the Holocaust 37 4. Encountering representations of the Holocaust in classrooms and beyond 71 Part III Historical knowledge and understanding of the Holocaust 99 Preface 101 5. Who were the victims? 105 6. -

Study Guide for Band of Brothers – Episode 9: Why We Fight

Study Guide for Band of Brothers – Episode 9: Why We Fight INTRO: Band of Brothers is a ten-part video series dramatizing the history of one company of American paratroopers in World War Two—E Company, 506th Regiment, 101st Airborne, known as “Easy Company.” Although the company’s first experience in real combat did not come until June 1944 ( D-Day), this exemplary group fought in some of the war’s most harrowing battles. Band of Brothers depicts not only the heroism of their exploits but also the extraordinary bond among men formed in the crucible of war. In the ninth episode, Easy Company finally enters Germany in April 1945, finding very little resistance as they proceed. There they are impressed by the industriousness of the defeated locals and gain respect for their humanity. But the G.I.s are then confronted with the horror of an abandoned Nazi concentration camp in the woods, which the locals claim not to have known anything about. Here the story of Easy Company is connected with the broader narrative of the war—the ideology of the Third Reich and Hitler’s plan to exterminate the Jews. CURRICULUM LINKS: Band of Brothers can be used in history classes. NOTE TO EDUCATORS: Band of Brothers is appropriate as a supplement to units on World War Two, not as a substitute for material providing a more general explanation of the war’s causes, effects, and greater historical significance. As with war itself, it contains graphic violence and language; it is not for the squeamish. Mature senior high school students, however, will find in it a powerful evocation of the challenges of war and the experience of U.S. -

WFLDP Leadership in Cinema – Band of Brothers Part Four, Replacements 2 of 14 Facilitator Reference

Facilitator Reference BAND OF BROTHERS PART FOUR: REPLACEMENTS Submitted by: R. Nordsven – E-681 Asst. Captain / C. Harris- E-681 Captain North Zone Fire Management, Black Hills National Forest E-mail: [email protected] Studio: HBO Pictures .......................................................................................... Released: 2001 Genre: War/Drama ........................................................................................ Audience Rating: R Runtime: 1 hour Materials VCR or DVD (preferred) television or projection system, Wildland Fire Leadership Values and Principles handouts (single-sided), notepads, writing utensils. Intent of Leadership in Cinema The Leadership in Cinema program is intended to provide a selection of films that will support continuing education efforts within the wildland fire service. Films not only entertain but also provide a medium to teach leadership at all levels in the leadership development process—self or team development. The program is tailored after Reel Leadership: Hollywood Takes the Leadership Challenge. Teaching ideas are presented that work with “students of leadership in any setting.” Using the template provided by Graham, Sincoff, Baker, and Ackerman, facilitators can adapt lesson plans to correlate with the Wildland Fire Leadership Values and Principles. Other references are provided which can be used to supplement the authors’ template. (Taken from the Leadership in Cinema website.) Lesson Plan Objective Students will identify Wildland Fire Leadership Values -

Study Guide for Band of Brothers – Episode 7: the Breaking Point

Study Guide for Band of Brothers – Episode 7: The Breaking Point INTRO: Band of Brothers is a ten-part video series dramatizing the history of one company of American paratroopers in World War Two—E Company, 506th Regiment, 101st Airborne, known as “Easy Company.” Although the company’s first experience in real combat did not come until June 1944 ( D-Day), this exemplary group fought in some of the war’s most harrowing battles. Band of Brothers depicts not only the heroism of their exploits but also the extraordinary bond among men formed in the crucible of war. As the title of this episode suggests, the seventh episode sees Easy Company pushed to “the breaking point” after more and more unrelenting combat. After successfully thwarting the German counterattack in the Ardennes, Easy Company is sent to take the Belgian town of Foy. The company suffers, however, from more casualties, sinking morale, and lapses in leadership. This episode, more than any other perhaps, depicts the great emotional and psychological strain that soldiers endured in battle. CURRICULUM LINKS: Band of Brothers can be used in history classes. NOTE TO EDUCATORS: Band of Brothers is appropriate as a supplement to units on World War Two, not as a substitute for material providing a more general explanation of the war’s causes, effects, and greater historical significance. As with war itself, it contains graphic violence and language; it is not for the squeamish. Mature senior high school students, however, will find in it a powerful evocation of the challenges of war and the experience of U.S. -

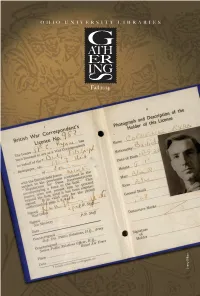

Gatherings, 2014 Fall

OHIO UNIVERSITY LIBRARIES Fall 2014 Sherry DiBari From the Dean of the Libraries MINING THE CORNELIUS RYAN ANYWHERE, ANYTIME: COLLECTION ACCESSING LIBRARIES’ MATERIALS PG 8 FINDING PARALLELS PG 5 IN THE FADING INK elebrating anniversaries is such C PG 2 an important part of our culture because MEET they underscore the value we place on TERRY MOORE heritage and tradition. Anniversaries PG 14 speak to our impulse to acknowledge the things that endure. Few places CLUES FROM AN embody those acknowledgements more AMERICAN than a library—the keeper of things LETTER that endure. As the offi cial custodian of PG 11 the University’s history and the keeper of scholarly records, no other entity on LISTENING TO OUR campus is more immersed in the history STUDENTS of Ohio University than the Libraries. PG 16 OUR DONORS A LASTING LEGACY PG 20 This year marks the 200th anniversary of Ohio University Libraries. It was on PG 18 June 15, 1814 that the Board of Trustees fi rst named their collection of books the “Library of Ohio University,” codifi ed a Credits list of seven rules for its use, and later Dean of Libraries: appointed the fi rst librarian. Scott Seaman Editor: In the 200 years since its founding, Kate Mason, coordinator of communications and assistant to the dean Ohio University Libraries is now Co-Editor: Jen Doyle, graduate communications assistant ranked as one of the top 100 research Design: libraries in North America with print University Communications and Marketing collections of over 3 million volumes Photography: and, ranked by holdings, is the 65th Sherry Dibari, graduate photography assistant largest library in North America. -

Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey

RUTGERS, THE STATE UNIVERSITY OF NEW JERSEY NEW BRUNSWICK AN INTERVIEW WITH ARNOLD SPIELBERG FOR THE RUTGERS ORAL HISTORY ARCHIVES WORLD WAR II * KOREAN WAR * VIETNAM WAR * COLD WAR INTERVIEW CONDUCTED BY SANDRA STEWART HOLYOAK and SHAUN ILLINGWORTH NEW BRUNSWICK, NEW JERSEY MAY 12, 2006 TRANSCRIPT BY DOMINGO DUARTE Shaun Illingworth: This begins an interview with Mr. Arnold Spielberg on May 12, 2006, in New Brunswick, New Jersey, with Shaun Illingworth and … Sandra Stewart Holyoak: Sandra Stewart Holyoak. SI: Thank you very much for sitting for this interview today. Arnold Spielberg: My pleasure. SI: To begin, could you tell us where and when you were born? AS: I was born February 6, 1917, in Cincinnati, Ohio. SH: Could you tell us a little bit about your father and how his family came to settle in Cincinnati, Ohio? AS: Okay. My father was an orphan, born in the Ukraine, in a little town called Kamenets- Podolski, in the Ukraine. … His parents died, I don’t know of what, when he was about two years old and he was raised by his uncle. His uncle’s name was Avrahom and his father’s name was Meyer Pesach, and so, I became Meyer Pesach Avrahom. So, I was named after both his uncle and his father, okay, and my father came to this country after serving six years in the Russian Army as a conscript. That is usually what happens to people. … Also, when he was raised on his uncle’s farm, he rode horses and punched cattle. So, he was sort of a Russian cowboy. -

J366E HISTORY of JOURNALISM University of Texas School of Journalism Spring 2012

J366E HISTORY OF JOURNALISM University of Texas School of Journalism Spring 2012 Instructor: Dr. Tom Johnson Office: CMA 5.155 Phone: 232-3831 email: [email protected] Office Hours: W, Th 1:30-3 by appointment and when you least expect it Class Time: 11-12:15 Tuesday and Thursday, CMA 3.120 REQUIRED READINGS Wm David Sloan, The Media in America: A History (8th Edition). Reading packet: available on Blackboard. COURSE DESCRIPTION Development of the mass media; social, economic, and political factors that have contributed to changes in the press. Three lecture hours a week for one semester. Prerequisite: Upper-division standing and a major in journalism, or consent of instructor. OBJECTIVES J 366E will trace the development of American media with an emphasis on cultural, technological and economic backgrounds of press development. To put it more simply, this course will examine the historic relationship between American society and the media. An underlying assumption of this class is that the content and values of the media have been greatly influenced by changes in society over the last 300 years. Conversely, the media have helped shape our society. More specifically, this course will: 1. Examine how journalistic values such as objectivity have evolved. 2. Explain how the media influenced society and how society influenced the media during different periods of our nation's history. 3. Examine who controlled the media at different periods of time, how that control was exercised and how that control influenced media content. 4. Investigate the relationship between the public and the media during different periods of time. -

Jimmy Carter: a Moral Hero (Student Essay)

Jimmy Carter: A Moral Hero (Student Essay) Danny Haidar (Utica Academy for International Studies) Abstract. Following the end of Jimmy Carter’s first and only term as President of the United States, historians scrambled to put his presidency in the proper context. More than thirty years later, Carter has become associated with failed presidencies. To be compared to him is to be insulted. Even so, Jimmy Carter has had one of the most prolific, philanthropic post-presidential lives of any former American president. This is inconsistent with the image of his single term in office that the media has painted—a good man should have been a good president. To better understand this irony, this investigation shall seek to answer the following question: how did Jimmy Carter’s pre-presidential experiences affect his leadership as President of the United States of America (1977-1981)? This article will draw on apolitical, supportive and critical accounts of Carter’s presidency, as well as Carter’s own accounts of his beliefs and childhood experiences. While historians interpret Carter’s life events differently, each interpretation reveals important influences on Carter’s leadership in the White House. I will argue that Carter held too tightly to his morals to be suited to presidency. Carter’s childhood and pre-presidential political experiences created a man who was, indeed, unfit for the White House. The problem was less with his political vision than it was with his execution of that vision. Carter’s tragic presidential tale serves as a reminder that moral malleability is a necessity in the highest office of a government.