Creative Writing Festival Participants

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Humour of Homer

The Humour of Homer Samuel Butler A lecture delivered at the Working Men's College, Great Ormond Street 30th January, 1892 The first of the two great poems commonly ascribed to Homer is called the Iliad|a title which we may be sure was not given it by the author. It professes to treat of a quarrel between Agamemnon and Achilles that broke out while the Greeks were besieging the city of Troy, and it does, indeed, deal largely with the consequences of this quarrel; whether, however, the ostensible subject did not conceal another that was nearer the poet's heart| I mean the last days, death, and burial of Hector|is a point that I cannot determine. Nor yet can I determine how much of the Iliadas we now have it is by Homer, and how much by a later writer or writers. This is a very vexed question, but I myself believe the Iliadto be entirely by a single poet. The second poem commonly ascribed to the same author is called the Odyssey. It deals with the adventures of Ulysses during his ten years of wandering after Troy had fallen. These two works have of late years been believed to be by different authors. The Iliadis now generally held to be the older work by some one or two hundred years. The leading ideas of the Iliadare love, war, and plunder, though this last is less insisted on than the other two. The key-note is struck with a woman's charms, and a quarrel among men for their possession. -

OH-00143; Aaron C. Kane and Sarah Taylor Kane

Transcript of OH-00143 Aaron C. Kane and Sarah Taylor Kane Interviewed by John Wearmouth on February 19, 1988 Accession #: 2006.034; OH-00143 Transcribed by Shannon Neal on 10/15/2020 Southern Maryland Studies Center College of Southern Maryland Phone: (301) 934-7626 8730 Mitchell Road, P.O. Box 910 E-mail: [email protected] La Plata, MD 20646 Website: csmd.edu/smsc The Stories of Southern Maryland Oral History Transcription Project has been made possible in part by a major grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH): Stories of Southern Maryland. https://www.neh.gov/ Any views, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this transcription, do not necessarily represent those of the National Endowment for the Humanities. Format Interview available as MP3 file or WAV: ssoh00143 (1:34:59) Content Disclaimer The Southern Maryland Studies Center offers public access to transcripts of oral histories and other archival materials that provide historical evidence and are products of their particular times. These may contain offensive language, negative stereotypes or graphic descriptions of past events that do not represent the opinions of the College of Southern Maryland or the Southern Maryland Studies Center. Typographic Note • [Inaudible] is used when a word cannot be understood. • Brackets are used when the transcriber is not sure about a word or part of a word, to add a note indicating a non-verbal sound and to add clarifying information. • Em Dash — is used to indicate an interruption or false start. • Ellipses … is used to indicate a natural extended pause in speech Subjects African American teachers Depressions Education Education, Higher Middle school principals School integration Segregation in education Tags Depression, 1929 Music teacher Aaron C. -

Which of the Following Signposts Was Featured in the Passage? Contrasts & Contradictions Aha Moment Tough Questions Words Of

Whitney’s face lit up when she saw me climb aboard the bus. “Right here, Lexi! You can sit beside me! I’ll even give you Which of the following signposts the window seat.” 1A I raised my eyebrows in surprise. “Um… okay!” I said as I was featured in the passage? plopped down in the seat beside Whitney. I had been dreading this new 45-minute bus ride ever since my parents announced Contrasts & Contradictions that we would be moving to an acreage outside of town. I knew Whitney rode this bus, but she and I had never been the best Aha Moment of friends. We just didn’t have that much in common. Whitney Tough Questions had been wearing makeup and flirting with boys since she was Words of the Wiser eight years old. I, on the other hand, had no interest in covering my face in a rainbow of colors. Furthermore, I only Again & Again ever talked to boys about our favorite sports teams, and I Memory Moment was a bit uncomfortable even doing that. “Hey, I had a question about math, Lex. Do you mind helping me?” she asked. “No, of course not,” I answered. She peeked inside her backpack. “Oh, I guess I forgot my math book at school. Do you have yours?” 1B I unzipped my backpack and dug out my math book, open- ing to our assignment. “Which part did you need help with?” “Actually, I think I can figure it out. Maybe I’ll just copy down your answers, and then when I’m doing my assignment Answer the question that follows later, I can check my answers against yours to just to make the signpost you identified. -

Notre Dame Review Notre Dame Review

NOTRE DAME REVIEW NOTRE DAME REVIEW NUMBER 8 Editors John Matthias William O'Rourke Senior Editor Steve Tomasula Founding Editor Valerie Sayers Managing Editor Editorial Assistants Kathleen J. Canavan Kelley Beeson Stacy Cartledge R. Thomas Coyne Contributing Editors Douglas Curran Matthew Benedict Jeanne DeVita Gerald Bruns Shannon Doyne Seamus Deane Anthony D'Souza Stephen Fredman Katie Lehman Sonia Gernes Marinella Macree Jere Odell Tom O'Connor Kymberly Taylor Haywood Rod Phasouk James Walton Ginger Piotter Henry Weinfield Laura Schafer Donald Schindler Elizabeth Smith-Meyer Charles Walton The Notre Dame Review is published semi-annually. Subscriptions: $15(individuals) or $20 (institu- tions) per year. Single Copy price: $8. Distributed by Media Solutions, Huntsville, Alabama and International Periodical Distributors, Solana Beach, California. We welcome manuscripts, which are read from September through April. Please include a SASE for return. Please send all subscription and editorial correspondence to: Notre Dame Review, The Creative Writing Program, Department of English, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, IN 46556. Notre Dame Review copyright 1999 by the University of Notre Dame ISSN: 1082-1864 Place/Displacement ISBN 1-892492-07-5 Cover Art: "Diagram for the Apprehension of Simple Forces," cibiachrome, 1997, 12 x 15 inches, by Jason Salavon. Courtesy of Peter Miller Gallery, Chicago. CONTENTS Genghis Khan story ..................................................................... 1 Yanbing Chen Anstruther; Knowledge; Alford -

Chapter 2 Music in the United States Before the Great Depression

American Music in the 20th Century 6 Chapter 2 Music in the United States Before the Great Depression Background: The United States in 1900-1929 In 1920 in the US - Average annual income = $1,100 - Average purchase price of a house = $4,000 - A year's tuition at Harvard University = $200 - Average price of a car = $600 - A gallon of gas = 20 cents - A loaf of Bread = 20 cents Between 1900 and the October 1929 stock market crash that triggered the Great Depression, the United States population grew By 47 million citizens (from 76 million to 123 million). Guided by the vision of presidents Theodore Roosevelt1 and William Taft,2 the US 1) began exerting greater political influence in North America and the Caribbean.3 2) completed the Panama Canal4—making it much faster and cheaper to ship its goods around the world. 3) entered its "Progressive Era" by a) passing anti-trust laws to Break up corporate monopolies, b) abolishing child labor in favor of federally-funded puBlic education, and c) initiating the first federal oversight of food and drug quality. 4) grew to 48 states coast-to-coast (1912). 5) ratified the 16th Amendment—estaBlishing a federal income tax (1913). In addition, by 1901, the Lucas brothers had developed a reliaBle process to extract crude oil from underground, which soon massively increased the worldwide supply of oil while significantly lowering its price. This turned the US into the leader of the new energy technology for the next 60 years, and opened the possibility for numerous new oil-reliant inventions. -

Academic Excellence … Personal Growth … Small School Environment Roadrunner

Building New Opportunities A publication of Sedona Charter School Enrichment Specials K-8 Tuition-free Montessori School Classrooms Without Walls Writing: SCS Staff and GC members Welcome to the Snack Shack! Photos: SCS Staff and parents The Suzuki Philosophy Design & Editing: Jane Cathcart Sights From Our Old-Fashioned Picnic academic excellence … personal growth … small school environment Roadrunner We want to take the opportunity to thank Patrons only concert in February, and you will receive 2 free tickets and reserved our parents, students and staff for working Our strings program is unique in around all of our construction these past seating at our winter and spring concerts in that we incorporate the tenets of several months. While not ideal, we are all the 2018-2019 school year. Suzuki Philosophy into our methods of doing our best to enjoy this new progress And for those of you who may have a teaching stringed instruments. In despite the inconveniences it may cause. tendency to worry, please don’t! The sharing the origins of the We are happy to announce that our tiny playground will be rebuilt across the parking philosophy and its basic principles, home for teacher KC O’Connor was lot as soon as the workers complete the we hope to help you and your completed in September and KC is Performing Arts Classroom. It is their final children progress through their enjoying her new home. Thanks to job on campus and the final piece of the musical journey. everyone who worked on the new deck and puzzle to get campus life “back to normal.” Dr. -

Schools' Budget Cut Down by $9.2 Million

FRFRONTONT PAGE A1 www.tooeletranscript.com TUESDAY TOOELE Monument RANSCRIPT dedicated to T the unborn See A2 BULLETIN MayM 25,25, 2010 SERVING TOOELE COUNTY SINCE 1894 VOL. 116 NO. 103 50¢ Schools’ budget cut down by $9.2 million instructional materials, adminis- tration and utilities. Overall, sala- Less money will result in fewer teachers ries make up 86 percent of the total district budget, according and larger class sizes in some grades to Richard Reese, Tooele County School District business adminis- by Tim Gillie school year by $7.1 million at its trator. STAFF WRITER meeting on May 18. That 8.7 per- “Reducing expenses this year cent cut was necessitated by a $2.1 will mean a reduction in expenses The Tooele County School million reduction in funding from for salaries,” Reese said. District has cut its 2010-11 budget the state and the loss of $4.8 mil- The district will look to make by 8.4 percent to $101 million — a lion in one-time federal stimulus up the shortfall by reducing its concession to decreased funding money the district received last roster of 740 full and part-time at a time when enrollment is once year. teaching positions by 18.5 posi- again expected to rise. The maintenance and opera- tions. The reduction will take place The Tooele County School tions budget comprises 74 percent through natural attrition — teach- District Board of Directors bal- of the district’s total budget for the ers retiring or leaving the district’s anced the new budget by chopping upcoming year. -

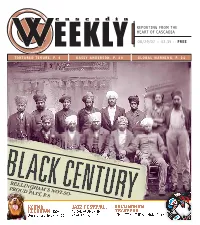

Cascadia BELLINGHAM's NOT-SO

cascadia REPORTING FROM THE HEART OF CASCADIA 08/29/07 :: 02.35 :: FREE TORTURED TENURE, P. 6 KASEY ANDERSON, P. 20 GLOBAL WARNING, P. 24 BELLINGHAM’S NOT-SO- PROUD PAST, P.8 HOUND JAZZ FESTIVAL: BELLINGHAM HOEDOWN: DOG AURAL ACUMEN IN TRAVERSE: DAYS OF SUMMER, P. 16 ANACORTES, P. 21 SIMULATING THE SALMON, P. 17 NURSERY, LANDSCAPING & ORCHARDS Sustainable ] 35 UNIQUE PLANTS Communities ][ FOOD FOR NORTHWEST & land use conference 28-33 GARDENS Thursday, September 6 ornamentals, natives, fruit ][ CLASSIFIEDS ][ LANDSCAPE & 24-27 DESIGN SERVICES ][ FILM Fall Hours start Sept. 5: Wed-Sat 10-5, Sun 11-4 20-23 Summer: Wed-Sat 10-5 , Goodwin Road, Everson Join Sustainable Connections to learn from key ][ MUSIC ][ www.cloudmountainfarm.com stakeholders from remarkable Cascadia Region 19 development featuring: ][ ART ][ Brownfields Urban waterfronts 18 Modern Furniture Fans in Washington &Canada Urban villages Urban growth areas (we deliver direct to you!) LIVE MUSIC Rural development Farmland preservation ][ ON STAGE ][ Thurs. & Sat. at 8 p.m. In addition, special hands on work sessions will present 17 the opportunity to get updates on, and provide feedback to, local plans and projects. ][ GET ][ OUT details & agenda: www.SustainableConnections.org 16 Queen bed Visit us for ROCK $699 BOTTOM Prices on Home Furnishings ][ WORDS & COMMUNITY WORDS & ][ 8-15 ][ CURRENTS We will From 6-7 CRUSH $699 Anyone’s Prices ][ VIEWS ][ on 4-5 ][ MAIL 3 DO IT IT DO $569 .07 29 A little out of the way… 08. But worth it. 1322 Cornwall Ave. Downtown Bellingham Striving to serve the community of Whatcom, Skagit, Island Counties & British Columbia CASCADIA WEEKLY #2.35 (Between Holly & Magnolia) 733-7900 8038 Guide Meridian (360) 354-1000 www.LeftCoastFurnishings.com Lynden, Washington www.pioneerford.net 2 *we reserve the right not to sell below our cost c . -

2016/17 Season Coming in the 2017/18 Season

A RAISIN IN THE SUN 2016/17 SEASON COMING IN THE 2017/18 SEASON Hot-Button Comedy World-Premire Power Play and NATIVE GARDENS Part of the Women’s Voices Theater Festival BY KAREN ZACARÍAS SOVEREIGNTY DIRECTED BY BLAKE ROBISON BY MARY KATHRYN NAGLE CO-PROUCTION WITH GUTHRIE THEATER DIRECTED BY MOLLY SMITH SEPTEMBER 15 — OCTOBER 22, 2017 JANUARY 12 — FEBRUARY 18, 2018 Good fences make good neighbors … right? In Mary Kathryn Nagle’s daring new work, From the outrageous mind of playwright a Cherokee lawyer fights to restore her Karen Zacarías (Destiny of Desire) comes Nation’s jurisdiction while confronting the ever this hot new comedy about the clash of present ghosts of her grandfathers. Arena’s class and culture that pushes well-meaning fourth Power Play world premiere travels the D.C. neighbors over the edge in a backyard intersections of personal and political truths, border dispute. and historic and present struggles. Golden Age Musical THE PAJAMA GAME BOOK BY GEORGE ABBOTT AND RICHARD BISSELL Epic Political Thrill Ride MUSIC AND LYRICS BY RICHARD ADLER AND JERRY ROSS THE GREAT SOCIETY BASED ON THE NOVEL 7½ CENTS BY RICHARD BISSELL BY ROBERT SCHENKKAN DIRECTED BY ALAN PAUL DIRECTED BY KYLE DONNELLY CHOREOGRAPHED BY PARKER ESSE FEBRUARY 2 — MARCH 11, 2018 MUSIC DIRECTION BY JAMES CUNNINGHAM Jack Willis reprises his performance as OCTOBER 27 — DECEMBER 24, 2017 President Lyndon Baines Johnson in this When a workers’ strike pits management sequel to the Tony Award-winning play All against labor, it ignites an outrageous the Way, bringing the second half of Robert battle of the sexes. -

Buffy & Angel Watching Order

Start with: End with: BtVS 11 Welcome to the Hellmouth Angel 41 Deep Down BtVS 11 The Harvest Angel 41 Ground State BtVS 11 Witch Angel 41 The House Always Wins BtVS 11 Teacher's Pet Angel 41 Slouching Toward Bethlehem BtVS 12 Never Kill a Boy on the First Date Angel 42 Supersymmetry BtVS 12 The Pack Angel 42 Spin the Bottle BtVS 12 Angel Angel 42 Apocalypse, Nowish BtVS 12 I, Robot... You, Jane Angel 42 Habeas Corpses BtVS 13 The Puppet Show Angel 43 Long Day's Journey BtVS 13 Nightmares Angel 43 Awakening BtVS 13 Out of Mind, Out of Sight Angel 43 Soulless BtVS 13 Prophecy Girl Angel 44 Calvary Angel 44 Salvage BtVS 21 When She Was Bad Angel 44 Release BtVS 21 Some Assembly Required Angel 44 Orpheus BtVS 21 School Hard Angel 45 Players BtVS 21 Inca Mummy Girl Angel 45 Inside Out BtVS 22 Reptile Boy Angel 45 Shiny Happy People BtVS 22 Halloween Angel 45 The Magic Bullet BtVS 22 Lie to Me Angel 46 Sacrifice BtVS 22 The Dark Age Angel 46 Peace Out BtVS 23 What's My Line, Part One Angel 46 Home BtVS 23 What's My Line, Part Two BtVS 23 Ted BtVS 71 Lessons BtVS 23 Bad Eggs BtVS 71 Beneath You BtVS 24 Surprise BtVS 71 Same Time, Same Place BtVS 24 Innocence BtVS 71 Help BtVS 24 Phases BtVS 72 Selfless BtVS 24 Bewitched, Bothered and Bewildered BtVS 72 Him BtVS 25 Passion BtVS 72 Conversations with Dead People BtVS 25 Killed by Death BtVS 72 Sleeper BtVS 25 I Only Have Eyes for You BtVS 73 Never Leave Me BtVS 25 Go Fish BtVS 73 Bring on the Night BtVS 26 Becoming, Part One BtVS 73 Showtime BtVS 26 Becoming, Part Two BtVS 74 Potential BtVS 74 -

2008 NGA Centennial Meeting

1 1 2 3 4 5 NATIONAL GOVERNORS ASSOCIATION 6 2008 CENTENNIAL MEETING 7 PHILADELPHIA, PENNSYLVANIA 8 9 - - - 10 11 PLENARY SESSION 12 JULY 13, 2008 13 CREATING A DIVERSE ENERGY PORTFOLIO 14 15 - - - 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 VERITEXT NATIONAL COURT REPORTING COMPANY 24 KNIPES COHEN 1801 Market Street - Suite 1800 25 Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19103 2 1 - - - I N D E X 2 - - - 3 PAGE 4 Governor Tim Pawlenty, Chair 3 5 6 Robert A. Malone, 18 Chairman and President, BP America, Inc. 7 8 Vijay V. Vaitheeswatan, 53 Award-Winning Correspondent, The Economist 9 10 Distinguished Service Awards 91 11 Corporate Fellows Tenure Awards 109 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 3 1 2 CHAIRMAN PAWLENTY: Good morning, 3 everybody; good morning, distinguished guests. 4 I now call to order the 100th 5 Annual Meeting of the National Governors 6 Association. I would like to begin by saying 7 what a privilege it has been to serve as the 8 National Governors Association Chair over these 9 past 12 months. 10 We also want to welcome all of 11 our governors here. We would like to have one 12 of our new governors here this morning as well, 13 Governor Paterson from New York, but I think he 14 was called back to New York on state business, 15 but we certainly welcome him and are excited to 16 get to know him better and work with him as one 17 of our colleagues. 18 At this session, along with 19 hearing from two notable speakers on creating a 20 diverse energy portfolio, we will recognize our 21 Distinguished Service Award winners and our 15- 22 and 20-year Corporate Fellows, but first we 23 need to do a little housekeeping and procedural 24 business, and I need to have a motion to adopt 25 the Rules of Procedure for the meeting, and I 4 1 2 understand Governor Rendell has been carefully 3 studying this motion and is prepared to make 4 a . -

Psychosocial Adaptation to Pregnancy Regina Lederman • Karen Weis

Psychosocial Adaptation to Pregnancy Regina Lederman • Karen Weis Psychosocial Adaptation to Pregnancy Seven Dimensions of Maternal Role Development Third Edition Regina Lederman Karen Weis University of Texas United States Air Force Galveston, TX School of Aerospace USA Medicine, Brooks-City Base [email protected] TX, USA [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] 1st Ed., Prentice Hall - November 1984 2nd Ed., Churchill Livingstone (Springer Publishing) - 1 Mar 1996 ISBN 978-1-4419-0287-0 e-ISBN 978-1-4419-0288-7 DOI 10.1007/978-1-4419-0288-7 Springer Dordrecht Heidelberg London New York Library of Congress Control Number: 2009933092 © Springer Science+Business Media, LLC 2009 All rights reserved. This work may not be translated or copied in whole or in part without the written permission of the publisher (Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, 233 Spring Street, New York, NY 10013, USA), except for brief excerpts in connection with reviews or scholarly analysis. Use in connection with any form of information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed is forbidden. The use in this publication of trade names, trademarks, service marks, and similar terms, even if they are not identified as such, is not to be taken as an expression of opinion as to whether or not they are subject to proprietary rights. Printed on acid-free paper Springer is part of Springer Science+Business Media (www.springer.com) Preface The subject of this book is the psychosocial development of gravid women, both primigravid and multigravid women.