Notre Dame Review Notre Dame Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1998-Fall.Pdf

Fall 98 Cover F&B_ Fall 98 Cover F&B 12/24/15 9:45 AM Page 3 Chicago EXPLORING NATURE & CULTURE WFALILL 19D98 ERNES S FIRE AS A FRIEND • T HINKING LIKE A SEED Fall cov 02 - 12_ Fall cov 02 - 12 12/24/15 10:10 AM Page cov2 is Chicago Wilderness? Chicago Wilderness is some of the finest and most signifi - cant nature in the temperate world, with roughly 200,000 acres of protected natural lands harboring native plant and animal communities that are more rare—and their survival more globally threatened—than the tropical rain forests. CHICAGO WILDERNESS is an unprecedented alliance of more than 60 public and private organizations working together to study and restore, protect and manage the precious natural resources of the Chicago region for the benefit of the public. Chicago WILDERNES S is a new quarterly magazine that seeks to articulate a vision of regional identity linked to nature and our natural heritage, to celebrate and promote the rich nat - ural areas of this region, and to inform readers about the work of the many organizations engaged in collaborative conservation. Fall cov 02 - 12_ Fall cov 02 - 12 12/24/15 10:10 AM Page 1 CHICAGO WILDERNESS A Regional Nature Reserve Keeping the Home Fires Burning or generations of us inculcated with the gospel according them, both by white men and by Indians—par accident; and Fto Smokey, setting fire to woods and prairies on purpose yet many more where it is voluntarily done for the purpose amounts to blasphemy. Yet those who love the land have of getting a fresh crop of grass, for the grazing of their horses, been wrestling with some new ideas about fire—new ideas and also for easier travelling during the next summer.” that are very old. -

Chapter 2 Music in the United States Before the Great Depression

American Music in the 20th Century 6 Chapter 2 Music in the United States Before the Great Depression Background: The United States in 1900-1929 In 1920 in the US - Average annual income = $1,100 - Average purchase price of a house = $4,000 - A year's tuition at Harvard University = $200 - Average price of a car = $600 - A gallon of gas = 20 cents - A loaf of Bread = 20 cents Between 1900 and the October 1929 stock market crash that triggered the Great Depression, the United States population grew By 47 million citizens (from 76 million to 123 million). Guided by the vision of presidents Theodore Roosevelt1 and William Taft,2 the US 1) began exerting greater political influence in North America and the Caribbean.3 2) completed the Panama Canal4—making it much faster and cheaper to ship its goods around the world. 3) entered its "Progressive Era" by a) passing anti-trust laws to Break up corporate monopolies, b) abolishing child labor in favor of federally-funded puBlic education, and c) initiating the first federal oversight of food and drug quality. 4) grew to 48 states coast-to-coast (1912). 5) ratified the 16th Amendment—estaBlishing a federal income tax (1913). In addition, by 1901, the Lucas brothers had developed a reliaBle process to extract crude oil from underground, which soon massively increased the worldwide supply of oil while significantly lowering its price. This turned the US into the leader of the new energy technology for the next 60 years, and opened the possibility for numerous new oil-reliant inventions. -

Strategic Analysis of the Coca-Cola Company

STRATEGIC ANALYSIS OF THE COCA-COLA COMPANY Dinesh Puravankara B Sc (Dairy Technology) Gujarat Agricultural UniversityJ 991 M Sc (Dairy Chemistry) Gujarat Agricultural University, 1994 PROJECT SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION In the Faculty of Business Administration Executive MBA O Dinesh Puravankara 2007 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Summer 2007 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author APPROVAL Name: Dinesh Puravankara Degree: Master of Business Administration Title of Project: Strategic Analysis of The Coca-Cola Company. Supervisory Committee: Mark Wexler Senior Supervisor Professor Neil R. Abramson Supervisor Associate Professor Date Approved: SIMON FRASER UNIVEliSITY LIBRARY Declaration of Partial Copyright Licence The author, whose copyright is declared on the title page of this work, has granted to Simon Fraser University the right to lend this thesis, project or extended essay to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. The author has further granted permission to Simon Fraser University to keep or make a digital copy for use in its circulating collection (currently available to the public at the "lnstitutional Repository" link of the SFU Library website <www.lib.sfu.ca> at: ~http:llir.lib.sfu.calhandle/l8921112>)and, without changing the content, to translate the thesislproject or extended essays, if technically possible, to any medium or format for the purpose of preservation of the digital work. -

2004/2005 Season!

_ _Inhalt _ _content Vorwort editorial ........................................................................................................................................................ 3 Musiktheater music theatre................................................................................................................................................ 5 Schauspiel drama Uraufführungen world premieres ................................................................................................................................. 15 Erstaufführungen debut performances........................................................................................................................... 44 Kinder- und Jugendtheater children’s and youth theatre Uraufführungen world premieres ................................................................................................................................. 54 Erstaufführungen debut performances ........................................................................................................................... 64 Adressen Verlage adresses publishing houses ........................................................................................................................... 67 Adressen Theater adresses theatres ........................................................................................................................................ 68 Abkürzungen / abbreviations UA = Uraufführung /world premiere DSE = Deutschsprachige Erstaufführung / debut performance in -

Schools' Budget Cut Down by $9.2 Million

FRFRONTONT PAGE A1 www.tooeletranscript.com TUESDAY TOOELE Monument RANSCRIPT dedicated to T the unborn See A2 BULLETIN MayM 25,25, 2010 SERVING TOOELE COUNTY SINCE 1894 VOL. 116 NO. 103 50¢ Schools’ budget cut down by $9.2 million instructional materials, adminis- tration and utilities. Overall, sala- Less money will result in fewer teachers ries make up 86 percent of the total district budget, according and larger class sizes in some grades to Richard Reese, Tooele County School District business adminis- by Tim Gillie school year by $7.1 million at its trator. STAFF WRITER meeting on May 18. That 8.7 per- “Reducing expenses this year cent cut was necessitated by a $2.1 will mean a reduction in expenses The Tooele County School million reduction in funding from for salaries,” Reese said. District has cut its 2010-11 budget the state and the loss of $4.8 mil- The district will look to make by 8.4 percent to $101 million — a lion in one-time federal stimulus up the shortfall by reducing its concession to decreased funding money the district received last roster of 740 full and part-time at a time when enrollment is once year. teaching positions by 18.5 posi- again expected to rise. The maintenance and opera- tions. The reduction will take place The Tooele County School tions budget comprises 74 percent through natural attrition — teach- District Board of Directors bal- of the district’s total budget for the ers retiring or leaving the district’s anced the new budget by chopping upcoming year. -

Cascadia BELLINGHAM's NOT-SO

cascadia REPORTING FROM THE HEART OF CASCADIA 08/29/07 :: 02.35 :: FREE TORTURED TENURE, P. 6 KASEY ANDERSON, P. 20 GLOBAL WARNING, P. 24 BELLINGHAM’S NOT-SO- PROUD PAST, P.8 HOUND JAZZ FESTIVAL: BELLINGHAM HOEDOWN: DOG AURAL ACUMEN IN TRAVERSE: DAYS OF SUMMER, P. 16 ANACORTES, P. 21 SIMULATING THE SALMON, P. 17 NURSERY, LANDSCAPING & ORCHARDS Sustainable ] 35 UNIQUE PLANTS Communities ][ FOOD FOR NORTHWEST & land use conference 28-33 GARDENS Thursday, September 6 ornamentals, natives, fruit ][ CLASSIFIEDS ][ LANDSCAPE & 24-27 DESIGN SERVICES ][ FILM Fall Hours start Sept. 5: Wed-Sat 10-5, Sun 11-4 20-23 Summer: Wed-Sat 10-5 , Goodwin Road, Everson Join Sustainable Connections to learn from key ][ MUSIC ][ www.cloudmountainfarm.com stakeholders from remarkable Cascadia Region 19 development featuring: ][ ART ][ Brownfields Urban waterfronts 18 Modern Furniture Fans in Washington &Canada Urban villages Urban growth areas (we deliver direct to you!) LIVE MUSIC Rural development Farmland preservation ][ ON STAGE ][ Thurs. & Sat. at 8 p.m. In addition, special hands on work sessions will present 17 the opportunity to get updates on, and provide feedback to, local plans and projects. ][ GET ][ OUT details & agenda: www.SustainableConnections.org 16 Queen bed Visit us for ROCK $699 BOTTOM Prices on Home Furnishings ][ WORDS & COMMUNITY WORDS & ][ 8-15 ][ CURRENTS We will From 6-7 CRUSH $699 Anyone’s Prices ][ VIEWS ][ on 4-5 ][ MAIL 3 DO IT IT DO $569 .07 29 A little out of the way… 08. But worth it. 1322 Cornwall Ave. Downtown Bellingham Striving to serve the community of Whatcom, Skagit, Island Counties & British Columbia CASCADIA WEEKLY #2.35 (Between Holly & Magnolia) 733-7900 8038 Guide Meridian (360) 354-1000 www.LeftCoastFurnishings.com Lynden, Washington www.pioneerford.net 2 *we reserve the right not to sell below our cost c . -

2016/17 Season Coming in the 2017/18 Season

A RAISIN IN THE SUN 2016/17 SEASON COMING IN THE 2017/18 SEASON Hot-Button Comedy World-Premire Power Play and NATIVE GARDENS Part of the Women’s Voices Theater Festival BY KAREN ZACARÍAS SOVEREIGNTY DIRECTED BY BLAKE ROBISON BY MARY KATHRYN NAGLE CO-PROUCTION WITH GUTHRIE THEATER DIRECTED BY MOLLY SMITH SEPTEMBER 15 — OCTOBER 22, 2017 JANUARY 12 — FEBRUARY 18, 2018 Good fences make good neighbors … right? In Mary Kathryn Nagle’s daring new work, From the outrageous mind of playwright a Cherokee lawyer fights to restore her Karen Zacarías (Destiny of Desire) comes Nation’s jurisdiction while confronting the ever this hot new comedy about the clash of present ghosts of her grandfathers. Arena’s class and culture that pushes well-meaning fourth Power Play world premiere travels the D.C. neighbors over the edge in a backyard intersections of personal and political truths, border dispute. and historic and present struggles. Golden Age Musical THE PAJAMA GAME BOOK BY GEORGE ABBOTT AND RICHARD BISSELL Epic Political Thrill Ride MUSIC AND LYRICS BY RICHARD ADLER AND JERRY ROSS THE GREAT SOCIETY BASED ON THE NOVEL 7½ CENTS BY RICHARD BISSELL BY ROBERT SCHENKKAN DIRECTED BY ALAN PAUL DIRECTED BY KYLE DONNELLY CHOREOGRAPHED BY PARKER ESSE FEBRUARY 2 — MARCH 11, 2018 MUSIC DIRECTION BY JAMES CUNNINGHAM Jack Willis reprises his performance as OCTOBER 27 — DECEMBER 24, 2017 President Lyndon Baines Johnson in this When a workers’ strike pits management sequel to the Tony Award-winning play All against labor, it ignites an outrageous the Way, bringing the second half of Robert battle of the sexes. -

Newfound Landing

Bear net girls push past Franklin Story on Page B1 THURSDAY,Newfound OCTOBER 15, 2015 FREE IN PRINT, FREE ON-LINE • WWW.NEWFOUNDLANDING.COM Landing COMPLIMENTARY Scarecrow contest ignites Halloween spirit in downtown Bristol BY DONNA RHODES town green while others help him keep vigil over [email protected] graced the storefronts of the town square. BRISTOL — “Ador- businesses up and down Students from local able,” “awesome,” and Lake Street. schools got involved as “fun” were just a few of Chris Hunewill and well, including a group the exclamations heard her granddaughter Mol- from Newfound Memo- around Central Square ly were among those who rial Middle School and last Saturday morning rose to the challenge and Joanne Robie’s fourth as folks gathered to see were pleased to see their grade class, which won the scarecrows that had efforts won them a prize for the best classroom cropped up overnight in in the Family category. entry. downtown Bristol. “We made a scare- Other entries includ- Sponsored by the crow together for my ed a Ninja Turtle and Bristol Events Com- house a few years ago, even Cat in the Hat, mittee, residents and and just thought it would while in the Individual businesses were invit- be a good idea to do it Adult category it was ed last month to build a again,” said Hunewill. Joanne Charette’s art- scarecrow of their own Their entry, which fully crafted witch who design then enter it in a eight-year-old Molly grabbed first prize this contest for cash prizes in dubbed “Bill the Farm- year. -

THE PLANETARIAN Journal of the International Planetarium Society

THE PLANETARIAN Journal of the International Planetarium Society Vol .. 18, No.1, March 1989 Articles 08 We're Regarded as Experts ............................................... Jeanne Bishop 11 Visions of the Universe ........................................................ Wayne Wyrick 14 Proximity: Stained Glass at Strasenburgh ................ Richard L. Hoover Features 19 Universe at Fingertips: Neptune/Pluto Bibliography ... Andrew Fraknoi 21 Computer Corner .................................................................. Keith Johnson 24 Book Reviews ..................................................... Carolyn Collins Petersen 26 Dr. Krocter ................................................................................... Norm Dean 27 Planetarium Usage for Secondary Students ............... Gerald L. Mallon 33 Script Section: 2061: Halley Rendezvous ...................... Jordan Marche and R. Erik Zimmermann 50 Focus on Education: A Modest Proposal .................... Mark S. Sonntag 52 Gibbous Gazette ............................................................... Donna C. Pierce 55 Secretary's Notepad ....................................................... Gerald L. Mallon 58 Regional Roundup .................................................................. Steven Mitch 66 Jane's Corner ................................................................... Jane G. Hastings The Planetarum (ISN 0090-3213) is published quarterly by the International Planetarium The Planetarian Society under the auspices of the Publications Committee. -

Poetic Connections in Tracy Letts's "Man from Nebraska," "August: Osage County," and "Superior Donuts."

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2011 How to Get from Here to There: Poetic Connections in Tracy Letts's "Man from Nebraska," "August: Osage County," and "Superior Donuts." Deborah Ann Kochman University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Literature Commons, and the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Scholar Commons Citation Kochman, Deborah Ann, "How to Get from Here to There: Poetic Connections in Tracy Letts's "Man from Nebraska," "August: Osage County," and "Superior Donuts."" (2011). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/3187 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. How to Get from Here to There: Poetic Connections in Tracy Letts‘s Man from Nebraska, August: Osage County, and Superior Donuts by Deborah Ann Kochman A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of English College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Sara Munson Deats, Ph.D. Lagretta Lenker, Ph.D. Susan Mooney, Ph.D. Date of approval: November 3, 2011 Five key words: Drama, Narrative, Poetry, Middle-aged men, American Dream Copyright © 2011 Deborah A. Kochman Dedication I dedicate this thesis to my children, Kristina and Michael, in apology for teaching too much narrative and not enough poetry. -

CPY Document

THE COCA-COLA COMPANY 795 795 Complaint IN THE MA TIER OF THE COCA-COLA COMPANY FINAL ORDER, OPINION, ETC., IN REGARD TO ALLEGED VIOLATION OF SEC. 7 OF THE CLAYTON ACT AND SEC. 5 OF THE FEDERAL TRADE COMMISSION ACT Docket 9207. Complaint, July 15, 1986--Final Order, June 13, 1994 This final order requires Coca-Cola, for ten years, to obtain Commission approval before acquiring any part of the stock or interest in any company that manufactures or sells branded concentrate, syrup, or carbonated soft drinks in the United States. Appearances For the Commission: Joseph S. Brownman, Ronald Rowe, Mary Lou Steptoe and Steven J. Rurka. For the respondent: Gordon Spivack and Wendy Addiss, Coudert Brothers, New York, N.Y. 798 FEDERAL TRADE COMMISSION DECISIONS Initial Decision 117F.T.C. INITIAL DECISION BY LEWIS F. PARKER, ADMINISTRATIVE LAW JUDGE NOVEMBER 30, 1990 I. INTRODUCTION The Commission's complaint in this case issued on July 15, 1986 and it charged that The Coca-Cola Company ("Coca-Cola") had entered into an agreement to purchase 100 percent of the issued and outstanding shares of the capital stock of DP Holdings, Inc. ("DP Holdings") which, in tum, owned all of the shares of capital stock of Dr Pepper Company ("Dr Pepper"). The complaint alleged that Coca-Cola and Dr Pepper were direct competitors in the carbonated soft drink industry and that the effect of the acquisition, if consummated, may be substantially to lessen competition in relevant product markets in relevant sections of the country in violation of Section 7 of the Clayton Act, as amended, 15 U.S.C. -

Soda Handbook

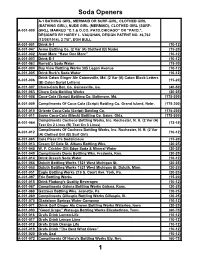

Soda Openers A-1 BATHING GIRL, MERMAID OR SURF-GIRL, CLOTHED GIRL (BATHING GIRL), NUDE GIRL (MERMAID), CLOTHED GIRL (SURF- A-001-000 GIRL), MARKED “C.T.& O.CO. PATD.CHICAGO” OR “PATD.”, DESIGNED BY HARRY L. VAUGHAN, DESIGN PATENT NO. 46,762 (12/08/1914), 2 7/8”, DON BULL A-001-001 Drink A-1 (10-12) A-001-047 Acme Bottling Co. (2 Var (A) Clothed (B) Nude) (15-20) A-001-002 Avon More “Have One More” (10-12) A-001-003 Drink B-1 (10-12) A-001-062 Barrett's Soda Water (15-20) A-001-004 Bay View Bottling Works 305 Logan Avenue (10-12) A-001-005 Drink Burk's Soda Water (10-12) Drink Caton Ginger Ale Catonsville, Md. (2 Var (A) Caton Block Letters A-001-006 (15-20) (B) Caton Script Letters) A-001-007 Chero-Cola Bot. Co. Gainesville, Ga. (40-50) A-001-063 Chero Cola Bottling Works (20-25) A-001-008 Coca-Cola (Script) Bottling Co. Baltimore, Md. (175-200) A-001-009 Compliments Of Coca-Cola (Script) Bottling Co. Grand Island, Nebr. (175-200) A-001-010 Oriente Coca-Cola (Script) Bottling Co. (175-200) A-001-011 Sayre Coca-Cola (Block) Bottling Co. Sayre, Okla. (175-200) Compliments Cocheco Bottling Works, Inc. Rochester, N. H. (2 Var (A) A-001-064 (12-15) Text On 2 Lines (B) Text On 3 Lines) Compliments Of Cocheco Bottling Works, Inc. Rochester, N. H. (2 Var A-001-012 (10-12) (A) Clothed Girl (B) Surf Girl) A-001-065 Cola Pleez It's Sodalicious (15-20) A-001-013 Cream Of Cola St.