Course Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

We'll Help Your Come True

6566 Route 22 Effective: January 1, 2012 Delmont, PA 15626 thelamplighterdelmont.com 724.468.4545 We’ll Help Your Dream Wedding Come True TRADITIONAL BUFFET PACKAGE Includes your choice of 6 Hot Selections, Salad Bar, coffee and tea, and 5 Hour Unlimited Bar, all Taxes and Gratuity.........$39.95 HOT SELECTIONS - CHOICE OF 6 • Steamship Round of Beef • Penne Marinara • Ham Carved by Chef • Au Gratin Potatoes • Baked Chicken • Parsley Potatoes • Beef Burgundy • Rice Pilaf • Seafood Newburg • Green Beans Almondine • Baked Scrod • Baby Carrots • Lasagna • Italian Mixed Vegetables • Stuffed Cabbage • Eggplant Parmigiana • Sweet Sausage • Italian or Swedish Meatballs SALAD BAR • Fresh Fruit Bowl • Potato Salad • Jello Salad • Tossed Salad • 3 Bean Salad • Relish Tray • Cole Slaw • Pasta Salad • Cottage Cheese w/Fruit • Broccoli Salad - add 25₵ 5 HOUR UNLIMITED OPEN BAR • Vodka • White Rum • Whiskey • Spiced Rum • Gin • Peach Schnapps • Scotch • Sodas and Juices • Bourbon • Miller Lite & Yuengling Bottles • Martinis, Manhattans, Whiskey Sours, etc • Red, White, and Blush Wines • Whiskey for Bridal Dance • Champagne for Bridal Table • No Shots Served GOLD BUFFET PACKAGE Includes your choice of 6 Hot Selections, Salad Bar, coffee and tea, and 5 Hour Unlimited Bar, all Taxes and Gratuity.......$44.95 HOT SELECTIONS - CHOICE OF 6 • Standing Prime Rib of Beef • Ricotta Stuffed Shells • Ham Carved by Chef • Stuffed Baked Potatoes • Chicken Marsala • Scalloped Potatoes • Chicken Picatta • Parsley Potatoes • Beef Burgundy • Penne Pasta a la Vodka • -

Thanksgiving Day 2018 at the Merion Inn Executive Chef Greg Baudermann

THANKSGIVING DAY 2018 AT THE MERION INN EXECUTIVE CHEF GREG BAUDERMANN APPETIZERS (included in price of full course dinner—see below) Roasted Red and Golden Beets with Crumbled Goat Cheese Caesar Salad with house croutons, shaved Parmesan and whole anchovies (optional) Pear and Arugula Salad with Roquefort Cheese and Pine Nuts maple-lemon dressing Jersey Shore Clam Chowder New England-style Pumpkin Bisque with toasted pumpkin seeds and a dollop of crème fraiche Mediterranean Seafood Salad with shrimp, mussels and calamari Sliced French Garlic Sausage over Lentils with cherry mostarda DINNER ENTRÉES (Entrée price includes 2 sides if not specified; 3-course dinner price includes an Appetizer and a Dessert) Roast Turkey with All the Trimmings! traditional sausage and bread stuffing, mashed potatoes, candied sweet potatoes, green beans, creamed pearl onions, giblet gravy, whole berry cranberry sauce Entrée only - 28 3-course dinner (with appetizer and dessert) – 39 Roast Turkey Express Lunch – 19 [served Noon-1:00 pm only] a smaller portion of roast turkey with stuffing, mashed potatoes, green beans and cranberry sauce, with a small salad and dessert, served all at once Grilled Salmon apricot-soy glaze, with coconut-pecan jasmine rice, sautéed spinach Entrée only - 28 3-course dinner – 39 Pan-Seared Cape May Scallops celery root purée, arugula and pignoli pesto, blistered cherry tomatoes Entrée only - 33 3-course dinner – 44 Merion Lobster Imperial fresh vegetable, Merion potato cup Entrée only - 38 3-course dinner – 49 Grilled Pork Chop with Pumpkin and Mushroom Risotto lingonberry demi-glace Entrée only - 28 3-course dinner – 39 Filet Mignon with Bearnaise Sauce mashed potatoes, fresh vegetable Entrée only - 33 3-course dinner – 44 New York Strip Steak with red wine demi-glace and two sides Entrée only (12 oz.)- 40 3-course dinner – 51 Roasted Portobello Mushrooms with Pumpkin and Mushroom Risotto Entrée only - 20 (with chicken (4 oz. -

Lesson Planning I N N O V a T I

Summer 2021 / Volume 79, Number 9 Digital Bonus Issue / www.ascd.org Tech tips for in-person learning p.8 Accelerate, don’t remediate p.14 Small-group instruction that works p.44 I N N O LESSON V A T I V PLANNING E Professional development for this crucial moment Engage students, no matt er where they’re learning Marzano Resources off ers a variety of professional development opportuniti es that will help you respond to the disrupti on in K–12 educati on and increase academic success for your students. Topics include: • Leadership • I n s t r u c ti o n • School Improvement • Curriculum • School Culture • Cogniti ve Skills • Collaborati on • Vocabulary • Student Agency • Assessment • Social-Emoti onal Learning • Grading & Reporti ng • Staff /Student Engagement • Personalized Learning • Teacher Eff ecti veness Learn More Resources MarzanoResources.com/2021PD Innovative Lesson Planning 8 Planning Technology Integration 38 Lesson Planning with Universal for In-Person Instruction Design for Learning Monica Burns Lee Ann Jung Strategic and resourceful use of technology doesn’t have to Using UDL principles upfront means making fewer adaptations disappear once distance learning does. later—and reaching more students. 14 Instructional Planning After 44 Planning for Fair Group Work a Year of Uncertainty Amir Rasooli and Susan M. Brookhart Craig Simmons Group projects have a bad reputation among students—but During pandemic recovery, schools must be especially educators can change that. intentional about planning and pacing. 50 Socratics, Remixed 20 How Innovative Teachers Can Start Henry Seton Teaching Innovation A lesson design for more focused and engaging student-led discussions. -

Helpful Information

As of March 22, 2017 GENERAL INFORMATION CONFERENCE REGISTRATION HOTEL INFORMATION Registration Fees The Coeur D’Alene Resort Date of Registration Before 5/19/17 After 5/19/17 115 S. 2nd Street ACLI Member Company $975 $1,075 Coeur d'Alene, ID 83814 Non-member $1,275 $1,475 Spouse/Guest* $275 $275 Room Reservations The Spouse/Guest fee includes daily breakfast, Monday Website: ACLI Reservations and Tuesday Lunch, as well as receptions nightly. By phone: 1-800-688-5253 * ACLI defines a “Guest” as a spouse, child or companion- Reference group ACLI Compliance & Legal Section 2017 not a professional colleague. A professional colleague is Meeting when calling for reservations. defined as someone who consults with or is employed by Room accommodations and rates have been reserved for an organization in the life insurance industry. Any person meeting participants. By reserving your room at the not meeting the criteria of “guest” who wishes to participate The Coeur D’Alene Resort, you are helping ACLI fulfill our in any ACLI function at the conference is required to contractual obligations, ultimately reducing the overall cost. register separately at the prevailing conference rate. Rate: Lake Tower $319/night, Park Tower $259/night and Registration Hours (Tentative) North Wing $219/night (All rooms are subject to applicable Monday, July 10 10:00 AM – 4:30 PM state and local taxes). Tuesday, July 11 7:00 AM – 5:00 PM Wednesday, July 12 8:00 AM – 11:00 AM Cutoff date for group room rate is June 9, 2017, or once the ACLI room block is filled (whichever comes first). -

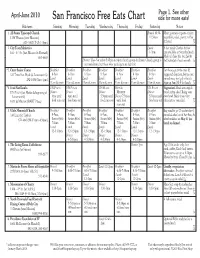

07-03-13 Eats Chart 2007 4-6:Eats 2007 04-06.Qxd

Page 1. See other April-June 2010 San Francisco Free Eats Chart side for more eats! Kitchens Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Notes 1. All Saints’ Episcopal Church Brunch 10:30- Meat; potatoes or pasta or rice; 1350 WALLER (near Masonic) 11:30am vegetables, salad, pastry, coffee 621-1862 (T-Th 1-5pm) & bread. 2. City Team Ministries Lunch A hot meal. Clothes & foot 164 - 6TH ST. (bet. Mission & Howard) 1-3pm. care available at Saturday lunch. 861-8688 Medical clinic the 1st, 2nd & Dinner: Tues-Sat arrive 5:45pm for 6pm church group & dinner. Church group is 3rd Saturday of each month. not mandatory, but those who participate are fed first. 3. Curry Senior Center Breakfast Breakfast Breakfast Breakfast Breakfast Breakfast Breakfast For those age 60 & over. $2 333 TURK (bet. Hyde & Leavenworth) 8-9am 8-9am 8-9am 8-9am 8-9am 8-9am 8-9am suggested donation, but no one 292-1086 (8am-1pm) Lunch Lunch Lunch Lunch Lunch Lunch Lunch turned away for lack of funds. 11am & noon 11am & noon 11am & noon 11am & noon 11am & noon 11am & noon 11am & noon Sign up 8am M-F for lunch. 4. Food Not Bombs UN PLAZA UN PLAZA UN PLAZA 16TH & UN PLAZA Vegetarian! Meals are soup & UN PLAZA (bet. Market & beginning of Dinner Dinner Dinner MISSION Dinner bread; often salad. Bring your Leavenworth) 6pm until 6pm until 5:30pm until Dinner 7:30pm 5:30pm until own bowl. Meal times vary: 16TH & MISSION (BART Plaza) food runs out food runs out food runs out until food food runs out often late or cancelled. -

Thanksgiving Day 2019

THANKSGIVING DAY 2019 AT THE MERION INN APPETIZERS (included in price of full course dinner—see below) Smoked Salmon Terrine with dill crème fraiche, pumpernickel toast, red onion and capers Grilled German Sausage with German potato salad, sweet-sour red cabbage and whole grain mustard Roasted Beet Salad with Greens and Crumbled Goat Cheese Honey Crisp Apple Salad crumbled gorgonzola cheese, mixed greens, radicchio, spiced walnuts, apple cider vinaigrette Garden Salad baby arugula with cherry tomatoes, cucumbers, red onion, carrots, honey-herb vinaigrette Caesar Salad with house croutons, shaved Parmesan and whole anchovies (optional) Apple, Leek and Potato Soup garnished with shredded Gruyère and toasted walnuts Jersey Shore Clam Chowder New England-style DINNER ENTRÉES (Entrée price includes specified sides; 3-course dinner price includes an Appetizer and a Dessert) Roast Turkey with All the Trimmings! traditional sausage and bread stuffing, mashed potatoes, maple-glazed sweet potatoes, green beans, creamed corn, giblet gravy, whole berry cranberry sauce Entrée only - 29 3-course dinner (with appetizer and dessert) – 40 Roast Turkey Express Lunch – 22 [served Noon-1:00 pm only] a smaller portion of roast turkey with stuffing, mashed potatoes, giblet gravy, green beans and cranberry sauce, with a small salad and dessert, served all at once Grilled Salmon apricot-tamari glaze, with coconut-pecan jasmine rice, sautéed spinach Entrée only - 28 3-course dinner – 39 Pan-Seared Cape May Scallops with butternut squash-sage risotto, wilted greens -

English for Cooks

English for Cooks Introductory handbook for culinary students Base in the Doc of Vilma Šiatkutė of the same name. Compilation and adaptation made by Arc. Elias Zanabria Ms.C. English for Cooks CONTENTS 1. Introduction …….……………..………………..………………………………………….……….….. 3 1.1. The ABC .….……………..……………….……………………………………………………….…. 3 1.2. Reading rules …………..………………….…………………………………….………….………. 3 2. At work: place and time………..…………………………….………………………..……….……… 4 2.1. Describing work place: Present Simple Tense, there is/ are, prepositions …….…...………….4 2.2. Indicating Time: prepositions, ordinal and cardinal numerals …………….………….………… 6 3. Kitchenware. Crockery and cutlery …………………………………………………..……………… 8 3.1. Kitchenware ………………..…………….…………………………………………………..……… 8 3.2. Crockery and cutlery ……..……………….……………………………………….………..…….. 11 4. Food and drink ………………………………………………………..……………………………… 13 4.1. Vocabulary. Names of food ……..…….………………………………………………………….. 13 4.2. Indicating likes and dislikes ………..…….……………………………………………………….. 13 4.3. Vocabulary. Names of drinks ………………..…………………………………………………… 15 4.4. Do you like and would you like ……….….………………………………………………………. 16 5. Breakfast ………………………………………..……………………………….……………………. 17 5.1. Meals of the day ……………………..……………….……………………………………………. 17 5.2. Continental Breakfast and English Breakfast …………..………………………………………. 17 5.3. Past Simple Tense ………………………………..…………….……………………..………….. 18 6. Lunch and Tiffin ………………………………………………………………………..…………….. 21 6.1. Lunch …………………………………..……………….………………………………..…………. 21 6.2. Tiffin …………………………..…..………………………………………………………………… -

Classic Wedding Package

Classic Wedding Package Exclusive use of 230-person ballroom with french doors to the expansive covered veranda Private use of gazebo area & access to gardens for photo opportunities Optional ceremony location with beautifully landscaped golf course as backdrop Bridal dressing suite with restroom Wedding Specialist to assist with planning process Wedding Manager on duty throughout wedding Chilled champagne toast for all guests Refreshments & hors d’oeuvres for the wedding party during picture taking Stationary hors d’oeuvre display for cocktail hour Selection of three butler-style passed hors d’oeuvres for cocktail hour Full course dinner & split entrée fee Custom wedding cake & cake cutting fee Gourmet coffee & tea station Taste testing for four Vendor meals for hired professionals Bar set up & two bartenders Five hour professional DJ service & custom uplighting Custom floral package including one bouquet for bride, one bouquet for honor attendant, four bouquets for bridesmaids, six boutonnieres for groomsmen & ushers, four corsages for mothers & grandmothers, four boutonnieres for fathers & grandfathers, draping head table centerpiece, toss bouquet & 15 vase florals for guest tables Photography package including seven hours of service, (24) 8x10s mounted in a handcrafted album, (12) 4x6s mounted in two parent’s albums & (1) 11x14 portrait suitable for framing A round of golf for four Floor length ivory swirl table linens & coordinating napkins Accent banquet table drapery Chiavari Chairs Off Season Rate: $125 per guest November through April; Fridays & Sundays Year Round In Season Rate: $135 per guest May through October; Holiday Weekends Year Round . -

Mapleside Farms Catering Menu

Mapleside Farms Catering Menu 16888 Pearl Road • Strongsville, Ohio 44136 • 440.845.0800 www.taste-food.com TABLE OF CONTENTS COMPANY POLICIES RISE AND SHINE BREAKFAST DECORATIVE DISPLAYS HORS D’OEUVRES - SEAFOOD AND CEVICHE SPOON BAR ACTION STATIONS FUSION AND TAPAS ACCOMPANIMENT DISHES DINNER ENTREES - CLAM BAKES AND SUMMERTIME FAVORITES - SWEET ENDINGS LATE NIGHT SNACKS BEVERAGES AND BAR SERVICE - WHAT MAKES A TASTE OF EXCELLENCE DIFFERENT? Our passion and devotion to hospitality. At each step of the planning process there is a professional to guide and assist you. Our planners and sales sta are supported by a team of experts in event execution and management, who review every detail in building an event. We bring to the table skill and attention, new and distinctive. No detail is considered inconsequential while we work to translate the vision in your mind’s eye into reality. Entertaining for business needs or entertaining for social events. We believe every bite of food should be A Taste of Excellence. Please keep in mind that the items in our menu are merely suggestions. We will gladly custom design your personalized menu and take responsibility for all support services such as china, silverware, glassware, linens, tables, chairs, tents, valet parking, entertainment and much more. CATERING POLICIES All menu prices are based on guests or more. For liability reasons, we do not permit outside food, with the exception of wedding cake, to be present at our catered events. If you have questions concerning this policy please contact our consultants. DELIVERY/PICK UP SERVICE All of our ne foods are available for delivery/pick up service. -

Hcm 436 Course Guide

COURSE GUIDE HCM 304 FOOD AND BEVERAGE PRODUCTION IV Course Team Dr. I. A. Akeredolu (Course Developer/Writer) – Yaba College of Technology, Lagos Dr. J. C. Okafor (Course Editor) – Federal Polytechnic, Ilaro Dr. (Mrs) A. O. Fagbemi (Programme Leader) – NOUN Mr. S. O. Israel-Cookey (Course Coordinator) – NOUN NATIONAL OPEN UNIVERSITY OF NIGERIA HCM 304 COURSE GUIDE National Open University of Nigeria Headquarters University Village Plot 91, Cadastral Zone, Nnamdi Azikiwe Express way Jabi, Abuja Lagos Office 14/16 Ahmadu Bello Way Victoria Island, Lagos e-mail: [email protected] website: www.nou.edu.ng Published by National Open University of Nigeria Printed 2015 ISBN: 978-058-641-1 All Rights Reserved ii HCM 304 COURSE GUIDE CONTENTS PAGE Introduction ..................................................................... iv Course Aims .................................................................... iv Course Objectives ........................................................... iv Working through this Course .......................................... v The Course Materials ...................................................... v Study Units ...................................................................... vi Assessment ...................................................................... vi Tutor-Marked Assignments (TMAs) .............................. vi Final Examination and Grading ...................................... vii How to Get the Most from this Course................................. .. vii Facilitators, Tutors -

DINNER MENU Full Course Dinner Prices Start at $22.50 Per Person and Include Salad, Entrée, Starch, Vegetable, Bread & Butter, Coffee and Dessert

DINNER MENU Full course dinner prices start at $22.50 per person and include salad, entrée, starch, vegetable, bread & butter, coffee and dessert. Price will be adjusted if any courses are not needed. These are just some suggestions to inspire your imagination - the choices are endless. Please feel free to call or schedule an appointment and we will tailor a menu just for you! SALADS SIDE DISHES Tossed Starches Caesar • Long Grain and Wild Rice Tropical • Rice Pilaf Greens, mandarin oranges, and strawberries with • Garlic Mashed Potatoes coconut mango dressing. • Mashed Potatoes House • Loaded Mashed Potatoes Greens, pears, walnuts, and gorgonzola with • Mashed Sweet Potatoes Balsamic Vinaigrette. • Potatoes au Gratin • Scalloped Potatoes ENTRÉES • Roasted Potatoes Beef • New Potatoes • Beef Tenderloin with béarnaise or port sauce Vegetables • Prime Rib with horseradish • Asparagus • Beef Stroganoff • Corn • Beef Burgundy • Green Beans Amandine • Beef Wellington • Baby Carrots Chicken • Honey Glazed Carrots • Chicken Piccata lemon butter wine sauce • Brandied Carrots & Artichoke Hearts • Chicken Marsala Marsala cream sauce with mushrooms • Ratatouille • Chicken Cordon Bleu • Roasted Vegetables (hot or cold) • Fruit Stuffed Chicken Breast with brandy plum sauce • Sautéed Zucchini & Yellow Squash • Chicken Juliette with peppers, onions, Bread and mushrooms in white wine • Assorted Rolls • Chicken Florentine in puff pastry • Garlic Bread Seafood • French Bread • Shrimp Creole • Key West Shrimp or Lobster cream sauce with sherry & Amaretto • Shrimp Scampi • Shrimp & Grits • Crab Cakes • Crab Imperial • Grouper Meuniere • Baked Swai Pork • Roast Pork Loin • Fruit Stuffed Pork Tenderloin with brandy apricot sauce Serving Personnel: $150.00 each for 5 hours; + $30.00 per hour over 5 hours. Serving Personnel for Weddings: $225.00 each for 6 hours; + $35.00 per hour over 6 hours. -

Thanksgiving

THANKSGIVING DAY 2014 AT THE MERION INN EXECUTIVE CHEF EDWARD HANCOCK APPETIZERS (included in price of full course dinner—see below) Butternut Squash Bisque Jersey Shore Clam Chowder Duet of House-Smoked Salmon and Bluefish, served with Horseradish Cream Sauce, Dilled Cucumber Salad Deviled Eggs with Maple-Cured Ham Salad in a “Nest” of Crispy Potato Sticks Roasted Pear, Spiced Walnut and Gorgonzola Salad with Apple Cider Vinaigrette Farmer’s Market Salad with Roasted Jersey Butternut Squash, Leeks, Carrots, Shallots, Wehani Rice, tossed with Maple Vinaigrette, topped with Julienned Red Beets Garden Salad with Fresh Veggies, Homemade Croutons and Choice of Dressing Grilled Knockwurst & Kielbasa Sausage Slices Made Locally by Gaiss’s Market, with Warm Red Bliss Potato & Bacon Salad, Red Cabbage & Apple Slaw and a Dollop of Creole Mustard DINNER ENTRÉES (À la carte price includes two sides; Full course dinner price includes sides plus Appetizer and Dessert) Roast Turkey with All the Trimmings! savory bread stuffing with roasted shallots, apples, celery and sage; mashed potatoes; giblet gravy; trio of vegetables (green beans almondine, fresh corn timbale and candied Jersey yams); and whole-berry cranberry- orange aspic (may substitute Merion potato cup or baked potato for mashed potatoes) À la carte - 24.95 Full course dinner – 33.95 Grilled Ginger-Soy Glazed Salmon with Grilled Bok Choy and Black and White Sticky Rice À la carte - 26.95 Full course dinner – 35.95 Pan-Seared Cape May Scallops with Parsnip Purée and Julienne Beet