Lesson Planning I N N O V a T I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Using Breakout Rooms in Synchronous Online Tutorials Kathy Chandler, the Open University (Associate Lecturer)

Vol 4 | Issue 3 (2016) | pp. 16-23 Using Breakout Rooms in Synchronous Online Tutorials Kathy Chandler, The Open University (Associate Lecturer) ABSTRACT This paper describes a small-scale, practitioner-led study of the use of breakout rooms for small group work in synchronous online tutorials using the Blackboard Collaborate tool. The project draws on the writer’s own experience of using breakout rooms in online tutorials over a period of 10 months, both as a tutor of two health and social care undergraduate modules and as a student of modules in a different faculty. It also draws on the experience of tutor colleagues. The project identifies three main benefits of using breakout rooms. Firstly, they are a useful tool for facilitating collaborative learning and interaction. Interaction takes on particular significance in online tutorials. In a face-to-face session the tutor can see if a student’s attention has wandered and gauge their response to the session. In contrast, a student can log into an online tutorial room and appear to be fully engaged with a lecture style session, whilst actually doing many other things and learning little. Interaction in an online tutorial also provides students learning at a distance with a rare opportunity for peer-to-peer contact, which can be invaluable in building relationships and confidence. Further benefits are identified in terms of empowering students to contribute to the session plan and content and also giving the tutor a break from presenting. Perceived barriers to breakout room use are identified around technical difficulties, small numbers of students and in terms of student skill and confidence. -

SILC-A SECURED INTERNET CHAT PROTOCOL Anindita Sinha1, Saugata Sinha2 Asst

ISSN (Print) : 2320 – 3765 ISSN (Online): 2278 – 8875 International Journal of Advanced Research in Electrical, Electronics and Instrumentation Engineering Vol. 2, Issue 5, May 2013 SILC-A SECURED INTERNET CHAT PROTOCOL Anindita Sinha1, Saugata Sinha2 Asst. Prof, Dept. of ECE, Siliguri Institute of Technology, Sukna, Siliguri, West Bengal, India 1 Network Engineer, Network Dept, Ericsson Global India Ltd, India2 Abstract:-. The Secure Internet Live Conferencing (SILC) protocol, a new generation chat protocol provides full featured conferencing services, compared to any other chat protocol. Its main interesting point is security which has been described all through the paper. We have studied how encryption and authentication of the messages in the network achieves security. The security has been the primary goal of the SILC protocol and the protocol has been designed from the day one security in mind. In this paper we have studied about different keys which have been used to achieve security in the SILC protocol. The main function of SILC is to achieve SECURITY which is most important in any chat protocol. We also have studied different command for communication in chat protocols. Keywords: SILC protocol, IM, MIME, security I.INTRODUCTION SILC stands for “SECURE INTERNET LIVE CONFERENCING”. SILC is a secure communication platform, looks similar to IRC, first protocol & quickly gained the status of being the most popular chat on the net. The security is important feature in applications & protocols in contemporary network environment. It is not anymore enough to just provide services; they need to be secure services. The SILC protocol is a new generation chat protocol which provides full featured conferencing services; additionally it provides security by encrypting & authenticating the messages in the network. -

The Effects of Synchronous Class Sessions on Students' Academic

THE EFFECTS OF SYNCHRONOUS CLASS SESSIONS ON STUDENTS’ ACADEMIC ACHIEVEMENT AND LEVELS OF SATISFACTION IN AN ONLINE INTRODUCTION TO COMPUTERS COURSE by Andrea Valene LeShea Liberty University A Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Education Liberty University October, 2013 THE EFFECTS OF SYNCHRONOUS CLASS SESSIONS ON STUDENTS’ ACADEMIC ACHIEVEMENT AND LEVELS OF SATISFACTION IN AN ONLINE INTRODUCTION TO COMPUTERS COURSE by Andrea Valene LeShea A Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Education Liberty University. Lynchburg VA October, 2013 APPROVED BY: Donna Joy, Ed.D. Committee Chair Joseph Fontanella, Ed.D. Committee Member Valery Hall, Ed.D.Committee Member Scott B. Watson, Ph.D. Associate Dean, Advanced Programs ABSTRACT The purpose of this quasi-experimental static-group comparison study was to test the theory of transactional distance that relates the inclusion of synchronous class sessions into an online introductory computer course to students’ levels of satisfaction and academic achievement at a post-secondary technical college. This study specifically looked at the effects of adding live, synchronous class sessions into an online learning environment using collaboration software such as Blackboard Collaborate and the impact that this form of live interaction had on students’ overall levels of satisfaction and academic achievement with the course. A quasi-experiment using the post-test only, static-group comparison design was utilized and conducted in an introductory computer class at a local technical college. It was determined that incorporating live, synchronous class sessions into an online course did not increase students’ levels of achievement, nor did it result in improved test scores. -

We'll Help Your Come True

6566 Route 22 Effective: January 1, 2012 Delmont, PA 15626 thelamplighterdelmont.com 724.468.4545 We’ll Help Your Dream Wedding Come True TRADITIONAL BUFFET PACKAGE Includes your choice of 6 Hot Selections, Salad Bar, coffee and tea, and 5 Hour Unlimited Bar, all Taxes and Gratuity.........$39.95 HOT SELECTIONS - CHOICE OF 6 • Steamship Round of Beef • Penne Marinara • Ham Carved by Chef • Au Gratin Potatoes • Baked Chicken • Parsley Potatoes • Beef Burgundy • Rice Pilaf • Seafood Newburg • Green Beans Almondine • Baked Scrod • Baby Carrots • Lasagna • Italian Mixed Vegetables • Stuffed Cabbage • Eggplant Parmigiana • Sweet Sausage • Italian or Swedish Meatballs SALAD BAR • Fresh Fruit Bowl • Potato Salad • Jello Salad • Tossed Salad • 3 Bean Salad • Relish Tray • Cole Slaw • Pasta Salad • Cottage Cheese w/Fruit • Broccoli Salad - add 25₵ 5 HOUR UNLIMITED OPEN BAR • Vodka • White Rum • Whiskey • Spiced Rum • Gin • Peach Schnapps • Scotch • Sodas and Juices • Bourbon • Miller Lite & Yuengling Bottles • Martinis, Manhattans, Whiskey Sours, etc • Red, White, and Blush Wines • Whiskey for Bridal Dance • Champagne for Bridal Table • No Shots Served GOLD BUFFET PACKAGE Includes your choice of 6 Hot Selections, Salad Bar, coffee and tea, and 5 Hour Unlimited Bar, all Taxes and Gratuity.......$44.95 HOT SELECTIONS - CHOICE OF 6 • Standing Prime Rib of Beef • Ricotta Stuffed Shells • Ham Carved by Chef • Stuffed Baked Potatoes • Chicken Marsala • Scalloped Potatoes • Chicken Picatta • Parsley Potatoes • Beef Burgundy • Penne Pasta a la Vodka • -

Thanksgiving Day 2018 at the Merion Inn Executive Chef Greg Baudermann

THANKSGIVING DAY 2018 AT THE MERION INN EXECUTIVE CHEF GREG BAUDERMANN APPETIZERS (included in price of full course dinner—see below) Roasted Red and Golden Beets with Crumbled Goat Cheese Caesar Salad with house croutons, shaved Parmesan and whole anchovies (optional) Pear and Arugula Salad with Roquefort Cheese and Pine Nuts maple-lemon dressing Jersey Shore Clam Chowder New England-style Pumpkin Bisque with toasted pumpkin seeds and a dollop of crème fraiche Mediterranean Seafood Salad with shrimp, mussels and calamari Sliced French Garlic Sausage over Lentils with cherry mostarda DINNER ENTRÉES (Entrée price includes 2 sides if not specified; 3-course dinner price includes an Appetizer and a Dessert) Roast Turkey with All the Trimmings! traditional sausage and bread stuffing, mashed potatoes, candied sweet potatoes, green beans, creamed pearl onions, giblet gravy, whole berry cranberry sauce Entrée only - 28 3-course dinner (with appetizer and dessert) – 39 Roast Turkey Express Lunch – 19 [served Noon-1:00 pm only] a smaller portion of roast turkey with stuffing, mashed potatoes, green beans and cranberry sauce, with a small salad and dessert, served all at once Grilled Salmon apricot-soy glaze, with coconut-pecan jasmine rice, sautéed spinach Entrée only - 28 3-course dinner – 39 Pan-Seared Cape May Scallops celery root purée, arugula and pignoli pesto, blistered cherry tomatoes Entrée only - 33 3-course dinner – 44 Merion Lobster Imperial fresh vegetable, Merion potato cup Entrée only - 38 3-course dinner – 49 Grilled Pork Chop with Pumpkin and Mushroom Risotto lingonberry demi-glace Entrée only - 28 3-course dinner – 39 Filet Mignon with Bearnaise Sauce mashed potatoes, fresh vegetable Entrée only - 33 3-course dinner – 44 New York Strip Steak with red wine demi-glace and two sides Entrée only (12 oz.)- 40 3-course dinner – 51 Roasted Portobello Mushrooms with Pumpkin and Mushroom Risotto Entrée only - 20 (with chicken (4 oz. -

Helpful Information

As of March 22, 2017 GENERAL INFORMATION CONFERENCE REGISTRATION HOTEL INFORMATION Registration Fees The Coeur D’Alene Resort Date of Registration Before 5/19/17 After 5/19/17 115 S. 2nd Street ACLI Member Company $975 $1,075 Coeur d'Alene, ID 83814 Non-member $1,275 $1,475 Spouse/Guest* $275 $275 Room Reservations The Spouse/Guest fee includes daily breakfast, Monday Website: ACLI Reservations and Tuesday Lunch, as well as receptions nightly. By phone: 1-800-688-5253 * ACLI defines a “Guest” as a spouse, child or companion- Reference group ACLI Compliance & Legal Section 2017 not a professional colleague. A professional colleague is Meeting when calling for reservations. defined as someone who consults with or is employed by Room accommodations and rates have been reserved for an organization in the life insurance industry. Any person meeting participants. By reserving your room at the not meeting the criteria of “guest” who wishes to participate The Coeur D’Alene Resort, you are helping ACLI fulfill our in any ACLI function at the conference is required to contractual obligations, ultimately reducing the overall cost. register separately at the prevailing conference rate. Rate: Lake Tower $319/night, Park Tower $259/night and Registration Hours (Tentative) North Wing $219/night (All rooms are subject to applicable Monday, July 10 10:00 AM – 4:30 PM state and local taxes). Tuesday, July 11 7:00 AM – 5:00 PM Wednesday, July 12 8:00 AM – 11:00 AM Cutoff date for group room rate is June 9, 2017, or once the ACLI room block is filled (whichever comes first). -

Abkürzungs-Liste ABKLEX

Abkürzungs-Liste ABKLEX (Informatik, Telekommunikation) W. Alex 1. Juli 2021 Karlsruhe Copyright W. Alex, Karlsruhe, 1994 – 2018. Die Liste darf unentgeltlich benutzt und weitergegeben werden. The list may be used or copied free of any charge. Original Point of Distribution: http://www.abklex.de/abklex/ An authorized Czechian version is published on: http://www.sochorek.cz/archiv/slovniky/abklex.htm Author’s Email address: [email protected] 2 Kapitel 1 Abkürzungen Gehen wir von 30 Zeichen aus, aus denen Abkürzungen gebildet werden, und nehmen wir eine größte Länge von 5 Zeichen an, so lassen sich 25.137.930 verschiedene Abkür- zungen bilden (Kombinationen mit Wiederholung und Berücksichtigung der Reihenfol- ge). Es folgt eine Auswahl von rund 16000 Abkürzungen aus den Bereichen Informatik und Telekommunikation. Die Abkürzungen werden hier durchgehend groß geschrieben, Akzente, Bindestriche und dergleichen wurden weggelassen. Einige Abkürzungen sind geschützte Namen; diese sind nicht gekennzeichnet. Die Liste beschreibt nur den Ge- brauch, sie legt nicht eine Definition fest. 100GE 100 GBit/s Ethernet 16CIF 16 times Common Intermediate Format (Picture Format) 16QAM 16-state Quadrature Amplitude Modulation 1GFC 1 Gigabaud Fiber Channel (2, 4, 8, 10, 20GFC) 1GL 1st Generation Language (Maschinencode) 1TBS One True Brace Style (C) 1TR6 (ISDN-Protokoll D-Kanal, national) 247 24/7: 24 hours per day, 7 days per week 2D 2-dimensional 2FA Zwei-Faktor-Authentifizierung 2GL 2nd Generation Language (Assembler) 2L8 Too Late (Slang) 2MS Strukturierte -

The Online Instructional Dynamic: a Study of Community College Faculty Teaching Online Courses and Their Perceptions of Barriers to Student Success

The Online Instructional Dynamic: A Study of Community College Faculty Teaching Online Courses and Their Perceptions of Barriers to Student Success A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty Of Drexel University by Jory Andrew Hadsell in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Education December 2012 © Copyright 2012 Jory Andrew Hadsell. All Rights Reserved. Abstract The Online Instructional Dynamic: A Study of Community College Faculty Teaching Online Courses and Their Perceptions of Barriers to Student Success Jory Andrew Hadsell, Ed.D. Drexel University, December 2012 Chairperson: W. Edward Bureau, Ph.D. Online students at some California community colleges are experiencing lower success rates than their peers in face-to-face versions of the same courses. Insight into the forces shaping student success in online courses is needed to address such disparities. The purpose of this study was to explore, in-depth, the lived experiences of faculty teaching courses online at a California community college to inform instructional practice so barriers to student success may be avoided. This online instructional dynamic is defined as the experiences surrounding instructor-student interaction, including factors impacted by the use of various technologies and instructional design approaches. The following questions guided the study: 1) How do faculty perceive their interactions with students in an online course? 2) What instructional practices do faculty believe have a positive impact on student success in their courses? 3) Why do faculty members believe the identified instructional practices have positive impacts on student success? A phenomenological research design was employed. Participants consisted of eight community college faculty with significant teaching experience in online Math, English, or Business courses. -

Athabasca University Synchronous Web

ATHABASCA UNIVERSITY SYNCHRONOUS WEB CONFERENCING: TOWARDS A PEDAGOGICAL MODEL FOR EFFECTIVE LEARNING BY SZE KIU YEUNG A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF EDUCATION IN DISTANCE EDUCATION CENTER FOR DISTANCE EDUCATION ATHABASCA UNIVERSITY MAY, 2014 © SZE KIU YEUNG SYNCHRONOUS WEB CONFERENCING Approval Page ii SYNCHRONOUS WEB CONFERENCING Acknowledgements It has never occurred to me that I would take up formal study at the doctoral level. The thought of committing myself to the discipline and rigor of research study seemed, at the time, beyond my grasp. Certainly, in a traditional face-to-face program, the “travel to class” time would have been higher, making the whole endeavor inefficient and less appealing. When Athabasca University (AU) and SIM University (UniSIM) signed a Memorandum of Understanding on academic exchanges at the faculty level, I was encouraged by my former Dean to consider studying in AU’s EdD in Distance Education program. At the beginning, three senior UniSIM Professors gave me the confidence to pursue this learning journey: Professor Tsui Kai Chong (Provost), Professor Koh Hian Chye (Assistant Provost, UniSIM College), and Associate Professor Neelam Aggarwal (Dean, School of Arts and Social Sciences – retired), and I am sincerely grateful to them for their guidance and support. In addition, I would also like to acknowledge the funding support (S$10,000) provided by UniSIM’s Center for Applied Research, which enabled me to implement the technological solution for this study. When I eventually enrolled on the program, I found the peer-support from my Cohort 2 class-mates, who are scattered around the world in different time-zones between North America, the Middle East, and East Asia, indispensible especially during the time when we were struggling with our research proposals. -

Viewpoints on Web Conferencing in Health Sciences Education (E39) Ruta Valaitis, Noori Akhtar-Danesh, Kevin Eva, Anthony Levinson, Bruce Wainman

Journal of Medical Internet Research Impact Factor (2018): 4.945 - ranked #1 medical informatics journal by Impact Factor Volume 9 (2007), Issue 5 ISSN: 1438-8871 Editor in Chief: Gunther Eysenbach, MD, MPH Contents Original Papers Feasibility of a Mobile Phone±Based Data Service for Functional Insulin Treatment of Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus Patients (e36) Alexander Kollmann, Michaela Riedl, Peter Kastner, Guenter Schreier, Bernhard Ludvik. 2 Mobile Web-Based Monitoring and Coaching: Feasibility in Chronic Migraine (e38) Marjolijn Sorbi, Sander Mak, Jan Houtveen, Annet Kleiboer, Lorenz van Doornen. 14 Pragmatists, Positive Communicators, and Shy Enthusiasts: Three Viewpoints on Web Conferencing in Health Sciences Education (e39) Ruta Valaitis, Noori Akhtar-Danesh, Kevin Eva, Anthony Levinson, Bruce Wainman. 24 No Increase in Response Rate by Adding a Web Response Option to a Postal Population Survey: A Randomized Trial (e40) Jan Brùgger, Wenche Nystad, Inger Cappelen, Per Bakke. 36 Review The Contribution of Teleconsultation and Videoconferencing to Diabetes Care: A Systematic Literature Review (e37) Fenne Verhoeven, Lisette van Gemert-Pijnen, Karin Dijkstra, Nicol Nijland, Erwin Seydel, Michaël Steehouder. 45 Journal of Medical Internet Research 2007 | vol. 9 | iss. 5 | p.1 XSL·FO RenderX JOURNAL OF MEDICAL INTERNET RESEARCH Kollmann et al Original Paper Feasibility of a Mobile Phone±Based Data Service for Functional Insulin Treatment of Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus Patients Alexander Kollmann1, MSc; Michaela Riedl2, MD; Peter Kastner1, MSc, -

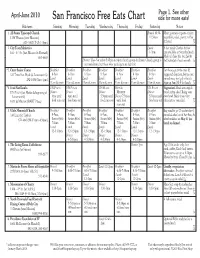

07-03-13 Eats Chart 2007 4-6:Eats 2007 04-06.Qxd

Page 1. See other April-June 2010 San Francisco Free Eats Chart side for more eats! Kitchens Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Notes 1. All Saints’ Episcopal Church Brunch 10:30- Meat; potatoes or pasta or rice; 1350 WALLER (near Masonic) 11:30am vegetables, salad, pastry, coffee 621-1862 (T-Th 1-5pm) & bread. 2. City Team Ministries Lunch A hot meal. Clothes & foot 164 - 6TH ST. (bet. Mission & Howard) 1-3pm. care available at Saturday lunch. 861-8688 Medical clinic the 1st, 2nd & Dinner: Tues-Sat arrive 5:45pm for 6pm church group & dinner. Church group is 3rd Saturday of each month. not mandatory, but those who participate are fed first. 3. Curry Senior Center Breakfast Breakfast Breakfast Breakfast Breakfast Breakfast Breakfast For those age 60 & over. $2 333 TURK (bet. Hyde & Leavenworth) 8-9am 8-9am 8-9am 8-9am 8-9am 8-9am 8-9am suggested donation, but no one 292-1086 (8am-1pm) Lunch Lunch Lunch Lunch Lunch Lunch Lunch turned away for lack of funds. 11am & noon 11am & noon 11am & noon 11am & noon 11am & noon 11am & noon 11am & noon Sign up 8am M-F for lunch. 4. Food Not Bombs UN PLAZA UN PLAZA UN PLAZA 16TH & UN PLAZA Vegetarian! Meals are soup & UN PLAZA (bet. Market & beginning of Dinner Dinner Dinner MISSION Dinner bread; often salad. Bring your Leavenworth) 6pm until 6pm until 5:30pm until Dinner 7:30pm 5:30pm until own bowl. Meal times vary: 16TH & MISSION (BART Plaza) food runs out food runs out food runs out until food food runs out often late or cancelled. -

ETSI SR 002 959 V1.1.1 (2011-08) Special Report

ETSI SR 002 959 V1.1.1 (2011-08) Special Report Electronic Working Tools; Roadmap including recommendations for the deployment and usage of electronic working tools in the ETSI standardization process 2 ETSI SR 002 959 V1.1.1 (2011-08) Reference DSR/BOARD-00010 Keywords audio, environment, quality, video ETSI 650 Route des Lucioles F-06921 Sophia Antipolis Cedex - FRANCE Tel.: +33 4 92 94 42 00 Fax: +33 4 93 65 47 16 Siret N° 348 623 562 00017 - NAF 742 C Association à but non lucratif enregistrée à la Sous-Préfecture de Grasse (06) N° 7803/88 Important notice Individual copies of the present document can be downloaded from: http://www.etsi.org The present document may be made available in more than one electronic version or in print. In any case of existing or perceived difference in contents between such versions, the reference version is the Portable Document Format (PDF). In case of dispute, the reference shall be the printing on ETSI printers of the PDF version kept on a specific network drive within ETSI Secretariat. Users of the present document should be aware that the document may be subject to revision or change of status. Information on the current status of this and other ETSI documents is available at http://portal.etsi.org/tb/status/status.asp If you find errors in the present document, please send your comment to one of the following services: http://portal.etsi.org/chaircor/ETSI_support.asp Copyright Notification No part may be reproduced except as authorized by written permission.