Charles' Childhood

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Great Expectations

Great Expectations 1 2 CONTENTS 1. The Encounter 26 2. The Chase 31 3. Summoned to Play 43 4. At Satis House 49 5. The Three Jolly Bargemen 59 6. At Miss Havisham’s 62 7. The Apprenticeship 70 8. Old Orlick 75 9. Drawn to Gentry 87 10. Farewell 102 11. In London with the Pockets 110 12. At the Castle 126 13. An Unexpected Call 134 14. A Heavy Heart 147 15. A Mind not at Ease 152 16. A Visit to the Castle 163 17. A Quarrel 169 18. Visitor of the Night 177 19. A Heart Poured Out 184 20. Pursued 201 21. The Ties 215 22. On The Run 228 23. Peace At Last 242 24. Good Old Joe 248 25. Back Home 255 3 Great Expectations Introduction Dickens’s Biography Born to a poor family on February 7th, 1812, in Portsmouth, Charles Dickens was the second of eight children. His father, John Dickens, was a naval clerk who dreamed of striking it rich while his mother, Elizabeth Barrow, hoped to be a teacher and school director. In 1816, they moved to Chatham, Kent, where young Charles spent the years that shaped his character and he and his siblings were free to roam the countryside and explore everything around. This period came to an end when in 1822, the Dickens family moved to Camden Town, a poor neighborhood in London. Although his father was a kind and pleasant man, he had a dangerous habit of living beyond the family’s means; so huge debts started accumulating and the family’s of Dickens the 1892 edition of Forster's financial situation worsened. -

Financialisation and the Thames Tideway Tunnel

King’s Research Portal DOI: 10.1177/0042098017736713 Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication record in King's Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Loftus, A. J., & March, H. (2019). Integrating what and for whom? Financialisation and the Thames Tideway Tunnel. URBAN STUDIES, 56(11), 2280-2296. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098017736713 Citing this paper Please note that where the full-text provided on King's Research Portal is the Author Accepted Manuscript or Post-Print version this may differ from the final Published version. If citing, it is advised that you check and use the publisher's definitive version for pagination, volume/issue, and date of publication details. And where the final published version is provided on the Research Portal, if citing you are again advised to check the publisher's website for any subsequent corrections. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Research Portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognize and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. •Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the Research Portal for the purpose of private study or research. •You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain •You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the Research Portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. -

Life of Charles Dickens

"(Sreat Writers." EDITED BY ERIC S. ROBERTSON, M.A., PROFESSOR OF ENGLISH LITERATURE AND PHILOSOPHY IN THE UNIVERSITY OF THE PUNJAB, LAHORE. LIFE OF DICKENS. LIFE OF CHARLES DICKENS BY FRANK T. ^ARZIALS LONDON WALTER SCOTT 24 WARWICK LANE, PATERNOSTER ROW 1887 NOTE. I should have to acknowledge a fairly hoavy " THATdebt to Forster's Life of Chi rles Dickens," and " The Letters of Charles Dickens," edited by his sister- in-law and his eldest daughter, is almost a matter of for which course ; these are books from every present and future biographer of Dickens must perforce borrow in a more or less degree. My work, too, has been much " lightened by Mr. Kitton's excellent Dickensiana." CONTENTS. CHAPTER I. PAGH born The of education ; Charles Dickens February 7, lottery "- his his 1812 ; pathetic feeling towards own childhood; at troubles be- happy days Chatham ; family ; similarity tween little Dickens Charles and David Copperfield ; John taken to the Marshalsea ; his character ; Charles employed in in after about blacking business ; over-sensitive years this in is back into episode his career ; isolation ; brought and in comfort at family prison circle ; family comparative the Marshalsea ; father released ; Charles leaves the his is sent to blacking business ; mother ; he Wellington House Academy in 1824; character of that place of learn- ing ; Dickens masters its humours thoroughly . .II CHAPTER II. a Dickens becomes a solicitor's clerk in 1827 ; then reporter; his first in experiences in that capacity ; story published The Old Monthly Magazine for January, 1834; writes more "Sketches"; power of minute observation thus early writer's art is for his contribu- shown ; masters the ; paid tions to the Chronicle; marries Miss Hogarth on April 2, at that of en- 1836 ; appearance date ; power physical his education durance ; admirable influence of peculiar ; and its drawbacks 27 CHAPTER III. -

Audience Insights Table of Contents

GOODSPEED MUSICALS AUDIENCE INSIGHTS TABLE OF CONTENTS JUNE 29 - SEPT 8, 2018 THE GOODSPEED Production History.................................................................................................................................................................................3 Synopsis.......................................................................................................................................................................................................4 Characters......................................................................................................................................................................................................5 Meet the Writer........................................................................................................................................................................................6 Meet the Creative Team.......................................................................................................................................................................7 Director's Vision......................................................................................................................................................................................8 The Kids Company of Oliver!............................................................................................................................................................10 Dickens and the Poor..........................................................................................................................................................................11 -

'Seeming Would Be Quite Enough'

‘Seeming Would Be Quite Enough’ Melodrama and Authenticity in Little Dorrit Helle Kathrine Løchen Knutsen A Thesis Presented to The Department of Literature, Area Studies and European Languages University of Oslo In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the MA Degree Spring Term 2013 Supervisor: Tore Rem Acknowledgements I grasp the opportunity to heartily thank my supervisor Professor Tore Rem, whose critical comments and encouragement have been greatly helpful. Further, I want to express my gratitude to my family. Their interest and support have been precious. Finally, I wish to thank my pupils, whose theatricals are a continuous source of inspiration. II III © Helle Kathrine Løchen Knutsen År: 2013 Title: ’Seeming Would Be Quite Enough’. Melodrama and Authenticity in Little Dorrit. Author: Helle Kathrine Løchen Knutsen Supervisor: Professor Tore Rem http://www.duo.uio.no Trykk: Reprosentralen, Universitetet i Oslo IV Sammendrag: ‘Seeming Would Be Quite Enough’ explores theatrical expressions in Little Dorrit (1855- 1857) by Charles Dickens. The many borrowings from entertainment culture, ranging from Punch and Judy to circus, add greatly to the impression of a remarkably many-faceted text. Fictive entertainers of four other novels, Nicholas Nickleby, The Old Curiosity Shop, Hard Times and Great Expectations are studied as representatives of various theatre forms of Dickens’s time, but they also display the author’s complex relationship to entertainers and acting. Little Dorrit clearly employs plot-structure similar to that of melodrama and the characteristic hyperbole, the ‘mode of excess’. Through the novel’s partly idealized and partly contorted depiction of human life there runs a strong yearning for authentic and genuine representation of language and communication. -

Life As a Thames Fisherman Once Thriving Smelt Fishery

THE STORY OF THE IN THE THAMES Fish from the Thames In the 19th century, the Thames in London provided a plentiful supply have fed Londoners for of fish to eat. Many fishing families thousands of years. relied on the river to make a living ONCE from selling fish like smelt, which Evidence of smelt bones was considered a delicacy. HAVE YOU The European smelt The presence of smelt indicates THRIVING in Medieval and Roman Beginning at age 9, fathers would an estuary has clean water and train their sons during a 7 year (Osmerus eperlanus) can support other wildlife. archaeological sites and the SMELT A wooden remains of Anglo- apprenticeship. On the Thames, is a fish with a silver The smelt’s story in the Thames SMELT fishermen used peterboats, which body that smells like teaches us about the need to Saxon fish traps, that can still had a well for holding live fish and SMELT? look after our river. FISHERY be seen in the river today, only had space for one man and a cucumber. show us that the significance a boy. In the early 1800s, records of smelt and other fishes show that fisherman and their stretches back over the entire apprentices only returned home history of London. once a month or every six weeks. Thames families fished the Fishers worked and lived closely together. waters from Teddington to Gravesend over many LIFE AS A generations. Most lived in small cottages as part of a THAMES close-knit community of fishing families along the FISHERMAN shores of the river. -

A Biographical Note on Charles Dickens *** Uma Nota Biográfica Sobre Charles Dickens

REVISTA ATHENA ISSN: 2237-9304 Vol. 14, nº 1 (2018) A BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE ON CHARLES DICKENS *** UMA NOTA BIOGRÁFICA SOBRE CHARLES DICKENS Sophia Celina Diesel1 Recebimento do texto: 25 de abril de 2018 Data de aceite: 27 de maio de 2018 RESUMO: As biografias de autores famosos costumam trazer supostas explicações para a sua obra literária. Foi o caso com Charles Dickens e a revelação do episódio da fábrica de graxa quando ele era menino, inspiração para David Copperfield. Exposta na biografia póstuma escrita pelo amigo próximo de Dickens John Forster, o episódio rapidamente tornou-se parte do imaginário Dickensiano. Porém é interessante observar mais de perto tais explicações e considerar outros pontos de vista, incluindo o do próprio autor. PALAVRAS-CHAVE: Charles Dickens; David Copperfield; Fábrica de Graxa; Literatura Vitoriana; Biografia literária. ABSTRACT: The biographies of famous authors often bring supposed explanations for their literary work, especially for complicated or obscure passages. Such was the case with Charles Dickens and the revelation of the blacking factory episode when he was a boy, which served later as inspiration for his novel David Copperfield. Exposed in the posthumous biography written by Dickens’s close friend John Forster it quickly called fan’s attention and became part of the Dickensian imaginary. Yet, it is interesting to look closer at such easy explanations and consider different views, including the author’s himself. KEYWORDS: Charles Dickens; David Copperfield; Blacking factory; Victorian literature; Literary biography. 1 Mestre pela Loughborough University, no Reino Unido, em Literatura Inglesa. Doutoranda em Estudos em Literatura na UFRGS - Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul. -

The Characters of a Christmas Carol Page 10: Pre and Post Show Questions & Discussion Starters Page 11: Resources Language Arts Core Curriculum Standards CCRR3

Theatre for Youth and Families A Christmas Carol Based on the story by Charles Dickens Adapted by David Bell Directed by Rosemary Newcott Study Guide, grades K-5 Created by the Counterpane Montessori Middle and High School Dramaturgy Team of Martha Spring and Katy Farr As part of the Alliance Theatre Institute for Educators and Teaching Artists’ Dramaturgy by Students program Under the guidance of Resident Teaching Artist Kim Baran Now in its 25th season, a magical holiday tradition for the whole family. On the Alliance Theatre stage November 21 through December 24, 2014 A Christmas Carol Study Guide 1 Happy Holidays from the Alliance Theatre! Welcome to the Alliance Theatre’s production of A Christmas Carol, written by Charles Dickens and adapted for stage by David H. Bell. This Study Guide has been created with the student audience in mind with the intent of providing a starting point as the audience prepares and then reflects together upon the Alliance Theatre for Youth and Families’ series production of A Christmas Carol. A note from the director, Rosemary Newcott, the Sally G. Tomlinson Artistic Director of Theatre for Youth and Families: “I think of this show as a gift to Atlanta . I always hope it reflects the look and spirit of our community. The message is one that never grows old – that one is still capable of change — no matter what your age or what you have experienced!” Table of Contents Page 3: Charles Dickens Page 4-5: Vocabulary **(see note below) Page 6: Cast of Characters; Synopsis of the story Page 7: Money of Victorian England Page 8: Design your Own Christmas Carol Ghost Costume! Page 9: Word Search: The Characters of A Christmas Carol Page 10: Pre and Post show questions & discussion starters Page 11: Resources Language Arts Core Curriculum Standards CCRR3. -

Highland Road Cemetery, Portsmouth

HIGHLAND ROAD CEMETERY, PORTSMOUTH A GUIDE TO THE “DICKENS” GRAVES a self-guided walk This information was provided to Portsmouth City Council by Professor A.J. Pointon from the Friends of Highland Road Cemetery and Dickens Fellowship GRAVE (see plan for location) ET Ellen Lawless Ternan (see “The Invisible Woman” by Claire Tomalin) was the love of Charles Dickens from 1857 to his death in 1870. Of a theatrical family, she met Dickens when he was in a play with her and her two sisters (see below). After Dickens died, she subtracted 10 years from her age and wed Rev. George Wharton Robinson in 1876; after he died, she gave up work (at real age 70) and went to live with Fanny in Victoria Grove, Southsea. She died in 1914, living on as Helen Landless in “Edwin Drood”. MT Maria Ternan, married name Taylor, lived with sister Fanny after they moved from London to Southsea; she died in 1903. Fanny, who had been introduced to Anthony Trollope’s brother Thomas by Dickens, and was his wife until he died in 1892, had been both actress and opera singer; she moved to Southsea in 1900 and died in 1913. SP Susan Pearce, daughter of John Dickens’s landlord, William Pearce (who lived in the grand house two doors down from the Birthplace Museum at 393 Commercial Road). Lived in 393 up to her death in 1903 when the Council were able to purchase it (See D below). WP This headstone commemorates the sons of William Pearce. William Baker Pearce (junior) shared a midwife (Mrs Purkiss) with Charles Dickens. -

London and Its Main Drainage, 1847-1865: a Study of One Aspect of the Public Health Movement in Victorian England

University of Nebraska at Omaha DigitalCommons@UNO Student Work 6-1-1971 London and its main drainage, 1847-1865: A study of one aspect of the public health movement in Victorian England Lester J. Palmquist University of Nebraska at Omaha Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/studentwork Recommended Citation Palmquist, Lester J., "London and its main drainage, 1847-1865: A study of one aspect of the public health movement in Victorian England" (1971). Student Work. 395. https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/studentwork/395 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Work by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LONDON .ML' ITS MAIN DRAINAGE, 1847-1865: A STUDY OF ONE ASPECT OP TEE PUBLIC HEALTH MOVEMENT IN VICTORIAN ENGLAND A Thesis Presented to the Department of History and the Faculty of the Graduate College University of Nebraska at Omaha In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts by Lester J. Palmquist June 1971 UMI Number: EP73033 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI EP73033 Published by ProQuest LLC (2015). Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. -

Westminster World Heritage Site Management Plan Steering Group

WESTMINSTER WORLD HERITAGE SITE MANAGEMENT PLAN Illustration credits and copyright references for photographs, maps and other illustrations are under negotiation with the following organisations: Dean and Chapter of Westminster Westminster School Parliamentary Estates Directorate Westminster City Council English Heritage Greater London Authority Simmons Aerofilms / Atkins Atkins / PLB / Barry Stow 2 WESTMINSTER WORLD HERITAGE SITE MANAGEMENT PLAN The Palace of Westminster and Westminster Abbey including St. Margaret’s Church World Heritage Site Management Plan Prepared on behalf of the Westminster World Heritage Site Management Plan Steering Group, by a consortium led by Atkins, with Barry Stow, conservation architect, and tourism specialists PLB Consulting Ltd. The full steering group chaired by English Heritage comprises representatives of: ICOMOS UK DCMS The Government Office for London The Dean and Chapter of Westminster The Parliamentary Estates Directorate Transport for London The Greater London Authority Westminster School Westminster City Council The London Borough of Lambeth The Royal Parks Agency The Church Commissioners Visit London 3 4 WESTMINSTER WORLD HERITAGE S I T E M ANAGEMENT PLAN FOREWORD by David Lammy MP, Minister for Culture I am delighted to present this Management Plan for the Palace of Westminster, Westminster Abbey and St Margaret’s Church World Heritage Site. For over a thousand years, Westminster has held a unique architectural, historic and symbolic significance where the history of church, monarchy, state and law are inexorably intertwined. As a group, the iconic buildings that form part of the World Heritage Site represent masterpieces of monumental architecture from medieval times on and which draw on the best of historic construction techniques and traditional craftsmanship. -

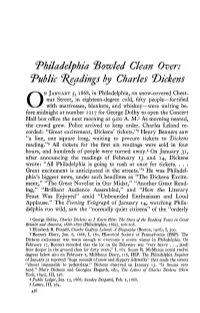

Readings by Charles 'Dickens

Philadelphia ^Bowled Clean Over: Public "Readings by Charles 'Dickens N JANUARY 5, 1868, in Philadelphia, on snow-covered Chest- nut Street, in eighteen-degree cold, fifty people—fortified O with mattresses, blankets, and whiskey—were waiting be- fore midnight at number 1217 for George Dolby to open the Concert Hall box office the next morning at 9:00 A. M.1 As morning neared, the crowd grew. Police arrived to keep order. Charles Leland re- corded: "Great excitement, Dickens' tickets."2 Henry Benners saw "a line, one square long, waiting to procure tickets to T)ickens reading."3 All tickets for the first six readings were sold in four hours, and hundreds of people were turned away.4 On January 31, after announcing the readings of February 13 and 14, Dickens wrote: "All Philadelphia is going to rush at once for tickets. Great excitement is anticipated in the streets."5 He was Philadel- phia's biggest news, under such headlines as "The Dickens Excite- ment," "The Great Novelist in Our Midst," "Another Great Read- Ing," "Brilliant Audience Assembled," and "How the Literary Feast Was Enjoyed" amid "Unbounded Enthusiasm and Loud Applause." The Evening "Telegraph of January 14, watching Phila- delphia run wild, saw the "normally quiet citizens" of the "orderly 1 George Dolby, Charles Dickens as I Knew Him: The Story of the Reading Tours in Great Britain and America, 1866-1870 (Philadelphia, 1885), 206-208. 2 Elizabeth R. Pennell, Charles Godfrey Leland: A Biography (Boston, 1906), I, 300. 3 Benners Diary, Jan. 6, 1868, I, 180, Historical Society of Pennsylvania (HSP).