Edinburgh Research Explorer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Join Us for a Dickens of a Celebration!

© www.byerschoice.com 2008 • Edition II Gerald Dickens Returns! Join us for a Dickens of a Celebration! September 27 – 28, 2008 We have planned lots of special happenings such as a chance to win a Trip for Two to London , a performance of “A Christmas Carol” by Charles Dickens’ great-great grandson Gerald Charles Dickens and special Caroler® event figures of Mr. and Mrs. Dickens. Gerald has told us that he will be happy to sign these pieces for you if you can catch him between performances. The weekend will be very festive with a huge birthday cake and English Tea and a chance to ride a double decker bus. You will also have an opportunity to design your own Caroler and tour the production floor. There will be lots of our “Old Friends” for sale and many retired pieces will be raffled off as prizes. For a complete update on our event happenings visit www.byerschoice.com . Event Figures: Some of the activities are already sold out but don’t let that discourage you. Charles and Catherine Dickens We promise lots of fun for everyone! 1 7 6 5 17 CAROLER ® CROSSWORD PUZZLE : 15 How well do you know your Carolers? See if you can identify the different characters that are numbered above in order to fill out our Caroler Crossword Puzzle (back page) . You can request a free catalog showing all of the 2008 figures at www.byerschoice.com 11 9 4 14 13 12 2 8 16 3 10 Witch on Broom & Halloween Cat New this Fall CAROLER ® CROSSWORD PUZZLE 4355 County Line Road P.O. -

Liminal Dickens

Liminal Dickens Liminal Dickens: Rites of Passage in His Work Edited by Valerie Kennedy and Katerina Kitsi-Mitakou Liminal Dickens: Rites of Passage in His Work Edited by Valerie Kennedy and Katerina Kitsi-Mitakou This book first published 2016 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2016 by Valerie Kennedy, Katerina Kitsi-Mitakou and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-8890-7 ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-8890-5 To Dimitra in love and gratitude (Katerina Kitsi-Mitakou) TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Illustrations ..................................................................................... ix List of Abbreviations ................................................................................... x Introduction ................................................................................................. 1 Liminal Dickens: Rites of Passage in His Work Valerie Kennedy, Katerina Kitsi-Mitakou Part I: Christian Births, Marriages and Deaths Contested Chapter One ............................................................................................... 20 Posthumous and Prenatal Dickens Dominic Rainsford Chapter -

A Biographical Note on Charles Dickens *** Uma Nota Biográfica Sobre Charles Dickens

REVISTA ATHENA ISSN: 2237-9304 Vol. 14, nº 1 (2018) A BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE ON CHARLES DICKENS *** UMA NOTA BIOGRÁFICA SOBRE CHARLES DICKENS Sophia Celina Diesel1 Recebimento do texto: 25 de abril de 2018 Data de aceite: 27 de maio de 2018 RESUMO: As biografias de autores famosos costumam trazer supostas explicações para a sua obra literária. Foi o caso com Charles Dickens e a revelação do episódio da fábrica de graxa quando ele era menino, inspiração para David Copperfield. Exposta na biografia póstuma escrita pelo amigo próximo de Dickens John Forster, o episódio rapidamente tornou-se parte do imaginário Dickensiano. Porém é interessante observar mais de perto tais explicações e considerar outros pontos de vista, incluindo o do próprio autor. PALAVRAS-CHAVE: Charles Dickens; David Copperfield; Fábrica de Graxa; Literatura Vitoriana; Biografia literária. ABSTRACT: The biographies of famous authors often bring supposed explanations for their literary work, especially for complicated or obscure passages. Such was the case with Charles Dickens and the revelation of the blacking factory episode when he was a boy, which served later as inspiration for his novel David Copperfield. Exposed in the posthumous biography written by Dickens’s close friend John Forster it quickly called fan’s attention and became part of the Dickensian imaginary. Yet, it is interesting to look closer at such easy explanations and consider different views, including the author’s himself. KEYWORDS: Charles Dickens; David Copperfield; Blacking factory; Victorian literature; Literary biography. 1 Mestre pela Loughborough University, no Reino Unido, em Literatura Inglesa. Doutoranda em Estudos em Literatura na UFRGS - Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul. -

Charles' Childhood

Charles’ Childhood His Childhood Charles Dickens was born on February 7, 1812 in Portsmouth. His parents were John and Elizabeth Dickens. Charles was the second of their eight children . John was a clerk in a payroll office of the navy. He and Elizabeth were an outgoing, social couple. They loved parties, dinners and family functions. In fact, Elizabeth attended a ball on the night that she gave birth to Charles. Mary Weller was an early influence on Charles. She was hired to care for the Dickens children. Her bedtime stories, stories she swore were quite true, featured people like Captain Murder who would make pies of out his wives. Young Charles Dickens Finances were a constant concern for the family. The costs of entertaining along with the expenses of having a large family were too much for John's salary. In fact, when Charles was just four months old the family moved to a smaller home to cut expenses. At a very young age, despite his family's financial situation, Charles dreamed of becoming a gentleman. However when he was 12 it looked like his dreams would never come true. John Dickens was arrested and sent to jail for failure to pay a debt. Also, Charles was sent to work in a shoe-polish factory. (While employed there he met Bob Fagin. Charles later used the name in Oliver Twist.) Charles was deeply marked by these experiences. He rarely spoke of this time of his life. Luckily the situation improved within a year. Charles was released from his duties at the factory and his father was released from jail. -

Readings by Charles 'Dickens

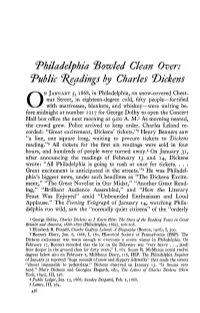

Philadelphia ^Bowled Clean Over: Public "Readings by Charles 'Dickens N JANUARY 5, 1868, in Philadelphia, on snow-covered Chest- nut Street, in eighteen-degree cold, fifty people—fortified O with mattresses, blankets, and whiskey—were waiting be- fore midnight at number 1217 for George Dolby to open the Concert Hall box office the next morning at 9:00 A. M.1 As morning neared, the crowd grew. Police arrived to keep order. Charles Leland re- corded: "Great excitement, Dickens' tickets."2 Henry Benners saw "a line, one square long, waiting to procure tickets to T)ickens reading."3 All tickets for the first six readings were sold in four hours, and hundreds of people were turned away.4 On January 31, after announcing the readings of February 13 and 14, Dickens wrote: "All Philadelphia is going to rush at once for tickets. Great excitement is anticipated in the streets."5 He was Philadel- phia's biggest news, under such headlines as "The Dickens Excite- ment," "The Great Novelist in Our Midst," "Another Great Read- Ing," "Brilliant Audience Assembled," and "How the Literary Feast Was Enjoyed" amid "Unbounded Enthusiasm and Loud Applause." The Evening "Telegraph of January 14, watching Phila- delphia run wild, saw the "normally quiet citizens" of the "orderly 1 George Dolby, Charles Dickens as I Knew Him: The Story of the Reading Tours in Great Britain and America, 1866-1870 (Philadelphia, 1885), 206-208. 2 Elizabeth R. Pennell, Charles Godfrey Leland: A Biography (Boston, 1906), I, 300. 3 Benners Diary, Jan. 6, 1868, I, 180, Historical Society of Pennsylvania (HSP). -

The Story of Jesus Told by Charles Dickens Kindle

THE LIFE OF OUR LORD: THE STORY OF JESUS TOLD BY CHARLES DICKENS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Charles Dickens | 144 pages | 08 May 2014 | Third Millennium Press Ltd. | 9781861189608 | English | Wiltshire, United Kingdom The Life of Our Lord: The Story of Jesus Told by Charles Dickens PDF Book First, it does not feel like a Dickens book. TMP, Hardcover. Included in the book are illustrations by Mormon artist Simon Dewey. Never forget this, when you are grown up. Jan 07, Lyn rated it it was amazing Shelves: children , young-adult. Stock Image. Reverend Frederick Buechner author of On the Road with the Archangel and Listening to Your Life Perhaps the most touching aspect of Charles Dickens's The Life of Our Lord is how in it he sets all his literary powers aside and tells the Gospel story in the simple, artless language of any father telling it to his children. And as he is now in Heaven, where we hope to go, and all meet each other after we are dead, and there be happy always together. On the other hand, Oscar Wilde, Henry James, and Virginia Woolf complained of a lack of psychological depth, loose writing, and a vein of saccharine sentimentalism. Many books are written on the life of our Savior that have impacted me more, but given this was written to his chi Good book. Charles Dickens. The family, many years after his death, decided to publish it, the underlying message being that they wanted the world to see the Charles Dickens they had grown up learning about: as a devoted father and devout Christian. -

Charles Dickens and His Cunning Manager George Dolby Made Millions from a Performance Tour of the United States, 1867-1868

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Communication Theses Department of Communication 12-17-2014 Making it in America: How Charles Dickens and His Cunning Manager George Dolby Made Millions from a Performance Tour of The United States, 1867-1868 Jillian Martin Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/communication_theses Recommended Citation Martin, Jillian, "Making it in America: How Charles Dickens and His Cunning Manager George Dolby Made Millions from a Performance Tour of The United States, 1867-1868." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2014. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/communication_theses/112 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Communication at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Communication Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MAKING IT IN AMERICA: HOW CHARLES DICKENS AND HIS CUNNING MANAGER GEORGE DOLBY MADE MILLIONS FROM A PERFORMANCE TOUR OF THE UNITED STATES, 1867-1868 by JILLIAN MARTIN Under the Direction of Leonard Teel, PhD ABSTRACT Charles Dickens embarked on a profitable journey to the United States in 1867, when he was the most famous writer in the world. He gave seventy-six public readings, in eighteen cities. Dickens and his manager, George Dolby, devised the tour to cash in on his popularity, and Dickens earned the equivalent of more than three million dollars. They created a persona of Dickens beyond the literary luminary he already was, with the help of the impresario, P.T. Barnum. Dickens became the first British celebrity to profit from paid readings in the United States. -

A Christmas Carol

November 13 – December 26, 2014 OneAmerica Stage STUDY GUIDE edited by Richard J Roberts & Milicent Wright contributors: Janet Allen, Courtney Sale Russell Metheny, Murell Horton, Michael Lincoln, Andrew Hopson Indiana Repertory Theatre 140 West Washington Street • Indianapolis, Indiana 46204 Janet Allen, Executive Artistic Director Suzanne Sweeney, Managing Director www.irtlive.com SEASON 2013-2014 YOUTH AUDIENCE FAMILY SERIES & MATINEE PROGRAMS SPONSOR 2 INDIANA REPERTORY THEATRE Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol adapted by Tom Haas The beloved classic of loss and redemption returns to IRT’s snow-covered stage! Dickens’ characters bring new life every season in this faithful, fanciful and frolicsome adaptation. It’s Indy’s favorite holiday tradition. Experience it for the first time all over again. Recommended for students in grades 4-12 Themes, Issues, & Topics the consequences of greed humanity’s ability to change the power of love and forgiveness The performance will last 90 minutes with no intermission. Study Guide Contents Synopsis 3 Author Charles Dickens 4 A Christmas Carol on Stage 6 Education Sales From the Designers 8 Randy Pease • 317-916-4842 From the Artistic Director 10 [email protected] From the Director 12 British Money in Scrooge’s Day 13 Pat Bebee • 317-916-4841 Victorian Life 14 [email protected] Music 16 Works of Art – Kyle Ragsdale 18 Outreach Programs Indiana Academic Standards 19 Milicent Wright • 317-916-4843 Resources 20 [email protected] Discussion Questions 23 Writing Prompts 24 Activities 25 Game: 20 Questions 26 Fifth Third Bank Financial Ed. 30 Text Glossary 31 Going to the Theatre 35 Young Playwrights in Process 36 Robert Neal in A Christmas Carol, 2010. -

{DOWNLOAD} Who Was Charles Dickens? Pdf Free Download

WHO WAS CHARLES DICKENS? PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Pamela D. Pollack,Meg Belviso | 112 pages | 01 Jan 2015 | Grosset and Dunlap | 9780448479675 | English | New York, United States Charles Dickens | Biography, Books, Characters, Facts, & Analysis | Britannica In he began submitting them to a magazine, The Monthly. He would later recall how he submitted his first manuscript, which he said was "dropped stealthily one evening at twilight, with fear and trembling, into a dark letter box, in a dark office, up a dark court in Fleet Street. When the sketch he'd written, titled "A Dinner at Poplar Walk," appeared in print, Dickens was overjoyed. The sketch appeared with no byline, but soon he began publishing items under the pen name "Boz. The witty and insightful articles Dickens wrote became popular, and he was eventually given the chance to collect them in a book. Buoyed by the success of his first book, he married Catherine Hogarth, the daughter of a newspaper editor. He settled into a new life as a family man and an author. Dickens was also approached to write the text to accompany a set of illustrations, and that project turned into his first novel, "The Pickwick Papers," which was published in installments from to This book was followed by "Oliver Twist," which appeared in Dickens became amazingly productive. In addition to these novels, Dickens was turning out a steady stream of articles for magazines. His work was incredibly popular. Dickens was able to create remarkable characters, and his writing often combined comic touches with tragic elements. His empathy for working people and for those caught in unfortunate circumstances made readers feel a bond with him. -

Charles Dickens

THE CAMBRIDGE COMPANION TO CHARLES DICKENS EDITED BY JOHN O. JORDAN published by the press syndicate of the university of cambridge The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom cambridge university press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge cb2 2ru,UK 40 West 20th Street, New York, ny 10011-4211,USA 477 Williamstown Road, Port Melbourne, vic 3207, Australia Ruiz de Alarcón 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain Dock House, The Waterfront, Cape Town 8001, South Africa http://www.cambridge.org © Cambridge University Press 2001 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 2001 Reprinted 2004 Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge Typeface Adobe Sabon 10/13pt System QuarkXPress™ [se] A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication data The Cambridge companion to Charles Dickens / edited by John O. Jordan. p. cm. – (Cambridge companions to literature) Includes bibliographical references (p. 224) and index. isbn 0 521 66016 5 – isbn 0 521 66964 2 (pb.) 1. Dickens, Charles, 1812–1870 – Criticism and interpretation. 2. Dickens, Charles, 1812–1870 – Handbooks, manuals, etc. i. Jordan, John O. ii. Series. pr4588.c26 2001 823′.8 –dc21 00-065162 isbn 0 521 66016 5 hardback isbn 0 521 66964 2 paperback CONTENTS List of illustrations page ix Notes on contributors xi Notes on references and editions xiv List of abbreviations xv Chronology xvi Preface xix john o. -

Aunt Georgy Preview

A play about the life and times of Charles Dickens. Now also available as a DVD. This is a preview script and can only be used for perusal purposes. A complete version of the script is available from FOX PLAYS with details on the final page. The life of Georgina Hogarth [A sister-in-law of Charles Dickens] Georgina Hogarth [Aunt Georgy] was a younger sister of Catherine Dickens the wife of the famous novelist Charles Dickens. Georgina lived with her sister and brother-in-law for many years, cared for their children, ran their house and was with the great man when he died. The Script Most, if not all, of the events in this play took place. Apart from the excerpts from plays, novels, books, articles and letters, the dialogue and plot are invented. Reviews of Aunt Georgy Aunt Georgy at Labassa offered audiences a very rewarding combination; an outstanding performance by Eileen Nelson as Aunt Georgy; a strong script by Cenarth Fox; and a wonderful setting in a mid-Victorian mansion that might have been built to house such a presentation. Eileen’s performance was virtually flawless. She was entirely convincing as she recounted her experiences in association with Dickens, from late childhood through to becoming housekeeper at Gad’s Hill, and subsequently guardian of Dickens’s reputation. Her account was by turns an exciting narrative, a confession, an accusation and a eulogy. In addition to acting out Aunt Georgy’s story, Eileen supplemented the narrative with recreations of Dickens’s own experiences. Especially memorable was he rendering of Dickens performing “Sikes and Nancy”. -

Dickens After Dickens, Pp

CHAPTER 10 Fictional Dickenses Emily Bell, Loughborough University Much as Charles Dickens’s own characters have appeared in various forms since their textual debuts – as discussed with relation to Miss Havisham in Chapter 4, Rosa Bud in Chapter 5, Little Nell in Chapter 7, and the full cast of Great Expectations in Chapter 9 – Dickens himself has been fictionalised in diverse ways throughout the 20th and 21st centuries. Some of these appear- ances are vastly popular among audiences who might not be particularly well versed in the author’s works, and do not aim for biographical specificity (for example, Gonzo’s turn as the Dickens-narrator in The Muppet Christmas Carol [1992], or Simon Callow as Dickens in an episode of Doctor Who, ‘The Unquiet Dead’ [2005]). Others have trod the line between biography and fiction une- venly, being read (and reviewed) as pure biography rather than biofiction, caus- ing dedicated Dickensians some headaches but being popularly received as fact. The line between biofiction and biography has long been blurred: as Michael Lackey notes, one of the foundational definitions of biofiction drawn from Carl Bode’s 1955 essay suggests that, ‘if a biography is either bad or stylized, then it would qualify as a biographical novel’ (Lackey 4); Georg Lukács had said some- thing similar in his 1937 study The Historical Novel, suggesting that the sub- ject’s ‘character is inevitably exaggerated, made to stand on tiptoe, his historical calling unduly emphasized … the personal, the purely psychological and bio- graphical acquire a disproportionate breadth, a false preponderance’ (314–21). That the biographical novel might be too biographical is a striking claim.