Liminal Dickens

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Join Us for a Dickens of a Celebration!

© www.byerschoice.com 2008 • Edition II Gerald Dickens Returns! Join us for a Dickens of a Celebration! September 27 – 28, 2008 We have planned lots of special happenings such as a chance to win a Trip for Two to London , a performance of “A Christmas Carol” by Charles Dickens’ great-great grandson Gerald Charles Dickens and special Caroler® event figures of Mr. and Mrs. Dickens. Gerald has told us that he will be happy to sign these pieces for you if you can catch him between performances. The weekend will be very festive with a huge birthday cake and English Tea and a chance to ride a double decker bus. You will also have an opportunity to design your own Caroler and tour the production floor. There will be lots of our “Old Friends” for sale and many retired pieces will be raffled off as prizes. For a complete update on our event happenings visit www.byerschoice.com . Event Figures: Some of the activities are already sold out but don’t let that discourage you. Charles and Catherine Dickens We promise lots of fun for everyone! 1 7 6 5 17 CAROLER ® CROSSWORD PUZZLE : 15 How well do you know your Carolers? See if you can identify the different characters that are numbered above in order to fill out our Caroler Crossword Puzzle (back page) . You can request a free catalog showing all of the 2008 figures at www.byerschoice.com 11 9 4 14 13 12 2 8 16 3 10 Witch on Broom & Halloween Cat New this Fall CAROLER ® CROSSWORD PUZZLE 4355 County Line Road P.O. -

Dombey and Son: an Inverted Maid's Tragedy

Advances in Language and Literary Studies ISSN: 2203-4714 Vol. 6 No. 3; June 2015 Flourishing Creativity & Literacy Australian International Academic Centre, Australia Dombey and Son: An Inverted Maid's Tragedy Taher Badinjki Department of English, Faculty of Arts, Al-Zaytoonah University P O box 1089 Marj Al-Hamam, Amman 11732, Jordan E-mail: [email protected] Doi:10.7575/aiac.alls.v.6n.3p.210 Received: 14/02/2014 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.7575/aiac.alls.v.6n.3p.210 Accepted: 29/04/2015 Abstract Ross Dabney, J. Butt & K. Tillotson, and others think that Dickens revised the role of Edith in the original plan of Dombey and Son upon the advice of a friend. I tend to believe that Dickens's swerve from his course was prompted by two motives, his relish for grand scenes, and his endeavour to engage the reader's sympathies for a character who was a victim of a social practice which he was trying to condemn. Dickens's humanitarian attitude sought to redeem the sinner and condemn the sin. In engaging the reader's sympathies, Dickens had entrapped his own. Both Edith and Alice are shown as victims of rapacious mothers who sell anything, or anybody for money. While Good Mrs Brown sells Alice's virtue and innocence for cash, Mrs Skewton trades on Edith's beauty in the marriage market to secure fortune and a good establishment. Edith and Alice's maturity and moral growth and their scorn and anger at their mothers' false teaching come in line with public prudery. -

FLORENCE AS CHRIST-FIGURE in DOMBEY and SON Sarah Flenniken John Carroll University, [email protected]

John Carroll University Carroll Collected Masters Essays Theses, Essays, and Senior Honors Projects Spring 2017 TOUCHED BY LOVE: FLORENCE AS CHRIST-FIGURE IN DOMBEY AND SON Sarah Flenniken John Carroll University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://collected.jcu.edu/mastersessays Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Flenniken, Sarah, "TOUCHED BY LOVE: FLORENCE AS CHRIST-FIGURE IN DOMBEY AND SON" (2017). Masters Essays. 61. http://collected.jcu.edu/mastersessays/61 This Essay is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Essays, and Senior Honors Projects at Carroll Collected. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Essays by an authorized administrator of Carroll Collected. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TOUCHED BY LOVE: FLORENCE AS CHRIST-FIGURE IN DOMBEY AND SON An Essay Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies College of Arts & Sciences of John Carroll University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts By Sarah Flenniken 2017 The essay of Sarah Flenniken is hereby accepted: ______________________________________________ __________________ Advisor- Dr. John McBratney Date I certify that this is the original document ______________________________________________ __________________ Author- Sarah E. Flenniken Date A recent movement in Victorian literary criticism involves a fascination with tactile imagery. Heather Tilley wrote an introduction to an essay collection that purports to “deepen our understanding of the interconnections Victorians made between mind, body, and self, and the ways in which each came into being through tactile modes” (5). According to Tilley, “who touched whom, and how, counted in nineteenth-century society” and literature; in the collection she introduces, “contributors variously consider the ways in which an increasingly delineated touch sense enabled the articulation and differing experience of individual subjectivity” across a wide range of novels and even disciplines (1, 7). -

A Biographical Note on Charles Dickens *** Uma Nota Biográfica Sobre Charles Dickens

REVISTA ATHENA ISSN: 2237-9304 Vol. 14, nº 1 (2018) A BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE ON CHARLES DICKENS *** UMA NOTA BIOGRÁFICA SOBRE CHARLES DICKENS Sophia Celina Diesel1 Recebimento do texto: 25 de abril de 2018 Data de aceite: 27 de maio de 2018 RESUMO: As biografias de autores famosos costumam trazer supostas explicações para a sua obra literária. Foi o caso com Charles Dickens e a revelação do episódio da fábrica de graxa quando ele era menino, inspiração para David Copperfield. Exposta na biografia póstuma escrita pelo amigo próximo de Dickens John Forster, o episódio rapidamente tornou-se parte do imaginário Dickensiano. Porém é interessante observar mais de perto tais explicações e considerar outros pontos de vista, incluindo o do próprio autor. PALAVRAS-CHAVE: Charles Dickens; David Copperfield; Fábrica de Graxa; Literatura Vitoriana; Biografia literária. ABSTRACT: The biographies of famous authors often bring supposed explanations for their literary work, especially for complicated or obscure passages. Such was the case with Charles Dickens and the revelation of the blacking factory episode when he was a boy, which served later as inspiration for his novel David Copperfield. Exposed in the posthumous biography written by Dickens’s close friend John Forster it quickly called fan’s attention and became part of the Dickensian imaginary. Yet, it is interesting to look closer at such easy explanations and consider different views, including the author’s himself. KEYWORDS: Charles Dickens; David Copperfield; Blacking factory; Victorian literature; Literary biography. 1 Mestre pela Loughborough University, no Reino Unido, em Literatura Inglesa. Doutoranda em Estudos em Literatura na UFRGS - Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul. -

Katie Wetzel MA Thesis Final SP12

DOMESTIC TRAUMA AND COLONIAL GUILT: A STUDY OF SLOW VIOLENCE IN DOMBEY AND SON AND BLEAK HOUSE BY KATHERINE E. WETZEL Submitted to the graduate degree program in English and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. _____________________________ Chairperson Dr. Dorice Elliott _____________________________ Dr. Anna Neill _____________________________ Dr. Paul Outka Date Defended: April 3, 2012 ii The Thesis Committee for Katherine E. Wetzel certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: DOMESTIC TRAUMA AND COLONIAL GUILT: A STUDY OF SLOW VIOLENCE IN DOMBEY AND SON AND BLEAK HOUSE _______________________________ Chairperson Dr. Dorice Elliott Date Approved: April 3, 2012 iii Abstract In this study of Charles Dickens’s Dombey and Son and Bleak House, I examine the two forms of violence that occur within the homes: slow violence through the naturalized practices of the everyday and immediate forms of violence. I argue that these novels prioritize the immediate forms of violence and trauma within the home and the intimate spaces of the family in order to avoid the colonial anxiety and guilt that is embedded in the naturalized practices of the everyday. For this I utilize Rob Nixon’s theory on slow violence, which posits that some practices and objects that occur as part of the everyday possess the potential to be just as violent as immediate forms of violence. Additionally, the British empire’s presence within the home makes the home a dark and violent place. Dombey and Son does this by displacing colonial anxiety, such as Mr. -

Domestic Trauma and Imperial Pessimism: the Crisis at Home in Charles Dickens’S Dombey and Son

CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture ISSN 1481-4374 Purdue University Press ©Purdue University Volume 21 (2019) Issue 5 Article 13 Domestic Trauma and Imperial Pessimism: The Crisis at Home in Charles Dickens’s Dombey and Son Katherine E. Ostdiek University of Iowa Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/clcweb Part of the American Studies Commons, Comparative Literature Commons, Education Commons, European Languages and Societies Commons, Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Other Arts and Humanities Commons, Other Film and Media Studies Commons, Reading and Language Commons, Rhetoric and Composition Commons, Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons, Television Commons, and the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Dedicated to the dissemination of scholarly and professional information, Purdue University Press selects, develops, and distributes quality resources in several key subject areas for which its parent university is famous, including business, technology, health, veterinary medicine, and other selected disciplines in the humanities and sciences. CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture, the peer-reviewed, full-text, and open-access learned journal in the humanities and social sciences, publishes new scholarship following tenets of the discipline of comparative literature and the field of cultural studies designated as "comparative cultural studies." Publications in the journal are indexed in the Annual Bibliography of English Language and Literature (Chadwyck-Healey), the Arts and Humanities Citation Index (Thomson Reuters ISI), the Humanities Index (Wilson), Humanities International Complete (EBSCO), the International Bibliography of the Modern Language Association of America, and Scopus (Elsevier). The journal is affiliated with the Purdue University Press monograph series of Books in Comparative Cultural Studies. -

The Treatment of Children in the Novels of Charles

THE TREATMENT OF CHILDREN IN THE NOVELS OF CHARLES DICKENS A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF ATLANTA UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS BY CLEOPATRA JONES DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH ATLANTA, GEORGIA AUGUST 1948 ? C? TABLE OF CONTENTS % Pag® PREFACE ii CHAPTER I. REASONS FOR DICKENS' INTEREST IN CHILDREN ....... 1 II. TYPES OF CHILDREN IN DICKENS' NOVELS 10 III. THE FUNCTION OF CHILDREN IN DICKENS' NOVELS 20 IV. DICKENS' ART IN HIS TREATMENT OF CHILDREN 33 SUMMARY 46 BIBLIOGRAPHY 48 PREFACE The status of children in society has not always been high. With the exception of a few English novels, notably those of Fielding, child¬ ren did not play a major role in fiction until Dickens' time. Until the emergence of the Industrial Revolution an unusual emphasis had not been placed on the status of children, and the emphasis that followed was largely a result of the insecure and often lamentable position of child¬ ren in the new machine age. Since Dickens wrote his novels during this period of the nineteenth century and was a pioneer in the employment of children in fiction, these facts alone make a study of his treatment of children an important one. While a great deal has been written on the life and works of Charles Dickens, as far as the writer knows, no intensive study has been made of the treatment of children in his novels. All attempts have been limited to chapters, or more accurately, to generalized statements in relation to his life and works. -

A Christmas Carol Adapted for the Stage by Geoff Elliott Directed by Julia Rodriguez-Elliott and Geoff Elliott December 2–23, 2021 Edu

A NOISE WITHIN HOLIDAY 2021 AUDIENCE GUIDE Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol Adapted for the stage by Geoff Elliott Directed by Julia Rodriguez-Elliott and Geoff Elliott December 2–23, 2021 Edu Pictured: Geoff Elliott and Deborah Strang. Photo by Craig Schwartz. TABLE OF CONTENTS Character Map ......................................3 Synopsis ...........................................4 Quotes from A Christmas Carol .........................5 About the Author Charles Dickens ......................6 Dickensian Timeline: Important Events in Dickens’ Life and Around the World ....8 Dickens’ Times: Victorian London .......................9 Poverty: Life & Death ................................12 Currency & Wealth. .16 About: Scenic Design. .18 About: Costume Design. .19 A Christmas Carol: Overall Design Concept ..............20 Additional Resources . .21 About A Noise Within. 22 A NOISE WITHIN’S EDUCATION PROGRAMS MADE POSSIBLE IN PART BY: Ann Peppers Foundation The Green Foundation Capital Group Companies Kenneth T. and Michael J. Connell Foundation Eileen L. Norris Foundation The Dick and Sally Roberts Ralph M. Parsons Foundation Coyote Foundation Steinmetz Foundation The Jewish Community Dwight Stuart Youth Fund Foundation 3 A NOISE WITHIN 2021/22 SEASON | Holiday 2021 Audience Guide A Christmas Carol CHARACTER MAP CHRISTMAS PAST CHRISTMAS PRESENT CHRISTMAS YET TO COME EBENEZER SCROOGE The protagonist: a bitter old creditor who does not believe in the spirit of Christmas, nor does he possess any sympathy for the poor. JACOB MARLEY GHOST OF CHRISTMAS GHOST OF CHRISTMAS “Dead to begin with.” PRESENT YET TO COME Ebenezer Scrooge’s former A lively spirit who spreads Scrooge fears this ghost’s business partner, who died seven Christmas cheer. premonitions. years prior. His ghost appears before Scrooge on Christmas Eve to warn of him of the Three Spirits, and urges him to choose a FRED OLD JOE, MRS. -

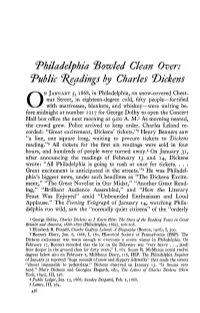

Readings by Charles 'Dickens

Philadelphia ^Bowled Clean Over: Public "Readings by Charles 'Dickens N JANUARY 5, 1868, in Philadelphia, on snow-covered Chest- nut Street, in eighteen-degree cold, fifty people—fortified O with mattresses, blankets, and whiskey—were waiting be- fore midnight at number 1217 for George Dolby to open the Concert Hall box office the next morning at 9:00 A. M.1 As morning neared, the crowd grew. Police arrived to keep order. Charles Leland re- corded: "Great excitement, Dickens' tickets."2 Henry Benners saw "a line, one square long, waiting to procure tickets to T)ickens reading."3 All tickets for the first six readings were sold in four hours, and hundreds of people were turned away.4 On January 31, after announcing the readings of February 13 and 14, Dickens wrote: "All Philadelphia is going to rush at once for tickets. Great excitement is anticipated in the streets."5 He was Philadel- phia's biggest news, under such headlines as "The Dickens Excite- ment," "The Great Novelist in Our Midst," "Another Great Read- Ing," "Brilliant Audience Assembled," and "How the Literary Feast Was Enjoyed" amid "Unbounded Enthusiasm and Loud Applause." The Evening "Telegraph of January 14, watching Phila- delphia run wild, saw the "normally quiet citizens" of the "orderly 1 George Dolby, Charles Dickens as I Knew Him: The Story of the Reading Tours in Great Britain and America, 1866-1870 (Philadelphia, 1885), 206-208. 2 Elizabeth R. Pennell, Charles Godfrey Leland: A Biography (Boston, 1906), I, 300. 3 Benners Diary, Jan. 6, 1868, I, 180, Historical Society of Pennsylvania (HSP). -

Dombey and Son: Charles Dickens and the Business of Family Monthly Course at the Rosenbach Syllabus

Dombey and Son: Charles Dickens and the Business of Family Monthly Course at the Rosenbach Syllabus Location: The Rosenbach 2008-2010 Delancey Place, Philadelphia, PA 19103 Time: Tuesdays, 6:00-7:45pm (for dates, see schedule below) Instructor: Christine Woody, Assistant Professor, Widener University [email protected] / (347) 243-1680 Contacts: Edward Pettit, Sunstein Manager of Public Programs [email protected] / (215) 732-1600 ext. 135 Texts: If you are in the market for a copy of our book, please consider seeking out the edition listed below. This will facilitate our discussions as pagination will be the same. However, please do feel free to use edition you may already own of our novel. Dickens, Charles. Dombey and Son. Penguin Classics. ISBN 978-0140435467. Goals & Approaches: Over our four monthly class sessions, we will dive deep into one of Dickens’ less-read masterpieces. Dealings with the Firm of Dombey and Son: Wholesale, Retail and for Exportation, serialized between October 1846 and April 1848, deals with the fate of the business and family (inextricably intertwined) of one Paul Dombey. The novel provides new insight into the connections between many of Dickens’ well-known social concerns—class conflict, cruelty to children, unhappy marriages, and the pressures of Victorian capitalism. As we wend our way through the novel’s rich tapestry of competing plotlines and compelling social portraiture, we will have the opportunity not only to consider how it reconfigures the themes and questions of more familiar novels (David Copperfield, Oliver Twist, and their ilk) but also to examine what Dombey and Son reveals about the questions we still ask ourselves today about the competing values of work and family and the process of reconciling them. -

Dombey and Son

Dombey and Son Charles Dickens Dombey and Son Table of Contents Dombey and Son........................................................................................................................................................1 Charles Dickens.............................................................................................................................................1 CHAPTER 1. Dombey and Son.....................................................................................................................1 CHAPTER 2. In which Timely Provision is made for an Emergency that will sometimes arise in the best−regulated Families................................................................................................................................9 CHAPTER 3. In which Mr Dombey, as a Man and a Father, is seen at the Head of the Home−Department......................................................................................................................................17 CHAPTER 4. In which some more First Appearances are made on the Stage of these Adventures..........25 CHAPTER 5. Paul's Progress and Christening............................................................................................34 CHAPTER 6. Paul's Second Deprivation....................................................................................................46 CHAPTER 7. A Bird's−eye Glimpse of Miss Tox's Dwelling−place: also of the State of Miss Tox's Affections....................................................................................................................................................60 -

Edinburgh Research Explorer

Edinburgh Research Explorer Trollope, Orley Farm, and Dickens' marriage break-down Citation for published version: O'Gorman, F 2018, 'Trollope, Orley Farm, and Dickens' marriage break-down', English Studies, pp. 1-19. https://doi.org/10.1080/0013838X.2018.1492228 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.1080/0013838X.2018.1492228 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Peer reviewed version Published In: English Studies Publisher Rights Statement: This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Taylor & Francis in English Studies on 21/9/2018, available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/0013838X.2018.1492228. General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 30. Sep. 2021 1 Trollope, Orley Farm, and Dickens’ Marriage Break-down Francis O’Gorman ABSTRACT Anthony Trollope’s Orley Farm (1861-2), the plot of which the novelist thought the best he had ever conceived, is peculiarly aware of Charles Dickens, the seemingly unsurpassable celebrity of English letters in the 1850s. This essay firstly examines narrative features of Orley Farm that indicate Dickens was on Trollope’s mind—and then asks why.