Dombey and Son: an Inverted Maid's Tragedy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Industrial Relations: Carlyle's Influence on Hard Times

Industrial Relations: Carlyle's influence on Hard Times Graham Law I. Introduction The aim of the present paper is the strictly limited one of presenting detailed internal evidence of the nature and extent of the influence of the writings of Thomas Carlyle on Charles Dickens's anti-utilitarian novel of 1854 Hard Times. The principal works of Carlyle in question here are: Sartor Resartus (1833-4, cited as SR), Chartism (1839, cited as CH), Past and Present (1843, cited as P&P), and Latter-Day Pamphlets (1850, cited as LDP), three works which return explicitly to the 'Condition-of-England question' first raised in the 1929 essay 'Signs of the Times' (cited as SofT), plus the History of the French Revolution (1837, cited as FR), a book less explicitly connected to the theme of industrialism but with which Dickens appears to have been especially familiar.1 Specific citations in the extensive exemplification which follows refer to the Centenary Edition of Carlyle's works, published in thirty volumes by Chapman & Hall in 1898, using the abbreviation CE. Citations from Hard Times refer to the 'Charles Dickens' edition published by Chapman and Hall in 1868, using the abbreviation HT. Citations from the weekly family journal Dickens conducted during the 1850s, Household Words, are indicated by the abbreviation HW. The wider implications of this material, in particular with regard to Dickens's contribution to the early Victorian genre of the industrial novel and the debate on industrialisation which Carlyle called 'the Condition-of-England question,'2 are here only briefly outlined but are discussed in greater detail elsewhere.3 The relative literary status of Carlyle's social criticism and Dickens's novel is now almost precisely the reverse of that pertaining when they were first received by the Victorian reading public. -

Liminal Dickens

Liminal Dickens Liminal Dickens: Rites of Passage in His Work Edited by Valerie Kennedy and Katerina Kitsi-Mitakou Liminal Dickens: Rites of Passage in His Work Edited by Valerie Kennedy and Katerina Kitsi-Mitakou This book first published 2016 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2016 by Valerie Kennedy, Katerina Kitsi-Mitakou and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-8890-7 ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-8890-5 To Dimitra in love and gratitude (Katerina Kitsi-Mitakou) TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Illustrations ..................................................................................... ix List of Abbreviations ................................................................................... x Introduction ................................................................................................. 1 Liminal Dickens: Rites of Passage in His Work Valerie Kennedy, Katerina Kitsi-Mitakou Part I: Christian Births, Marriages and Deaths Contested Chapter One ............................................................................................... 20 Posthumous and Prenatal Dickens Dominic Rainsford Chapter -

1854 HARD TIMES Charles Dickens 2

1 1854 HARD TIMES Charles Dickens 2 Dickens, Charles (1812-1870) - The most popular and perhaps greatest English novelist and short-story writer, he drew on his experiences as a poor child to produce extremely realistic stories. Hard Times (1854) - Thomas Gradgrind is an educator who believes only in the demonstrable fact. He raises his children, Louisa and Thomas, in a grim materialistic atmosphere that adversely affects their entire lives. “Hard Times” is an indictment of the values of 19th century industrial England. 3 Table Of Contents BOOK THE FIRST CHAPTER 1 . .. 6 The One Thing Needful CHAPTER 2 . 7 Murdering the Innocents CHAPTER 3 . 12 A Loophole CHAPTER 4 . 16 Mr Bounderby CHAPTER 5 . 22 The Key-note CHAPTER 6 . 27 Sleary’s Horsemanship CHAPTER 7 . 38 Mrs Sparsit CHAPTER 8 . 43 Never Wonder CHAPTER 9 . 48 Sissy’s Progress CHAPTER 10 . 54 Stephen Blackpool CHAPTER 11 . 59 No Way Out CHAPTER 12 . 65 The Old Woman CHAPTER 13 . .69 Rachael CHAPTER 14 . 75 The Great Manufacturer CHAPTER 15 . 79 Father and Daughter CHAPTER 16 . 85 Husband and Wife BOOK THE SECOND CHAPTER 1 . 91 Effects in the Bank CHAPTER 2 . 102 Mr James Harthouse CHAPTER 3 . 109 The Whelp CHAPTER 4 . 113 Men and Brothers 4 CHAPTER 5 . 120 Men and Masters CHAPTER 6 . 126 Fading Away CHAPTER 7 . 136 Gunpowder CHAPTER 8 . 146 Explosion CHAPTER 9 . 156 Hearing the Last of it CHAPTER 10 . 163 Mrs Sparsit’s Staircase CHAPTER 11 . 167 Lower and Lower CHAPTER 12 . 174 Down BOOK THE THIRD CHAPTER 1 . 179 Another Thing Needful CHAPTER 2 . -

FLORENCE AS CHRIST-FIGURE in DOMBEY and SON Sarah Flenniken John Carroll University, [email protected]

John Carroll University Carroll Collected Masters Essays Theses, Essays, and Senior Honors Projects Spring 2017 TOUCHED BY LOVE: FLORENCE AS CHRIST-FIGURE IN DOMBEY AND SON Sarah Flenniken John Carroll University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://collected.jcu.edu/mastersessays Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Flenniken, Sarah, "TOUCHED BY LOVE: FLORENCE AS CHRIST-FIGURE IN DOMBEY AND SON" (2017). Masters Essays. 61. http://collected.jcu.edu/mastersessays/61 This Essay is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Essays, and Senior Honors Projects at Carroll Collected. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Essays by an authorized administrator of Carroll Collected. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TOUCHED BY LOVE: FLORENCE AS CHRIST-FIGURE IN DOMBEY AND SON An Essay Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies College of Arts & Sciences of John Carroll University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts By Sarah Flenniken 2017 The essay of Sarah Flenniken is hereby accepted: ______________________________________________ __________________ Advisor- Dr. John McBratney Date I certify that this is the original document ______________________________________________ __________________ Author- Sarah E. Flenniken Date A recent movement in Victorian literary criticism involves a fascination with tactile imagery. Heather Tilley wrote an introduction to an essay collection that purports to “deepen our understanding of the interconnections Victorians made between mind, body, and self, and the ways in which each came into being through tactile modes” (5). According to Tilley, “who touched whom, and how, counted in nineteenth-century society” and literature; in the collection she introduces, “contributors variously consider the ways in which an increasingly delineated touch sense enabled the articulation and differing experience of individual subjectivity” across a wide range of novels and even disciplines (1, 7). -

Troubled Masculinity at Midlife: a Study of Dickens's Hard Times

235 Troubled Masculinity at Midlife: A Study of Dickens’s Hard Times HATADA Mio Hard Timesで提示される “Fact”と“Fancy”の2つの対照的な世界、あるいは価値観は、一見 すると相反するもののように思われるが、この小説は両者の対立よりもむしろ、両者がいかに 密接な関係を持っているかを暗示しているように思われる。そして、主要な登場人物は複雑に 絡まり合ったこれら2つの世界に、それぞれのやり方で関わりを持ち、反応を示す。興味深い ことに、2つの絡み合う世界は、主要な人物(その多くは中年の男性である)の抱えている問 題とも密接な関係を持っている。本稿ではHard Timesにおける2つの世界を、作品中で直接姿 を現すことのないSissy の父親の存在を手がかりに、中年期の男性が経験するmasculinityの危 機、という観点から再考している。 キーワード:aging, masculinity, gender Introduction It is well known that F. R. Leavis included Hard Times in his work The Great Tradition, calling it “a completely serious work of art” (Leavis 258) with the “subtlety of achieved art” (Leavis 279). Much earlier, John Ruskin estimated the novel as “the greatest” of Dickens’s novels, and asserted that it “should be studied with close and earnest care by persons interested in social questions” (34). Many other critics make much of the aspect of Hard Times as a critique of the contemporary society, and it has often been treated with other industrial novels such as Elizabeth Gaskell’s North and South (1855). Humphry House, for instance, points out that Dickens was “thinking much more about social problems,” and that “Hard Times is one of Dickens’s most thought-about books.” He goes on to assert that “in the ’fi fties, his novels begin to show a greater complication of plot than before” because “ he was intending to use them as a vehicle of more concentrated sociological argument” (House 205). David Lodge, too, affi rms, “Hard Times manifests its identity as a polemical work, a critique of mid-Victorian industrial society dominated by materialism, acquisitiveness and ruthlessly competitive capitalist economics,” which are “represented... by the Utilitarians” (Lodge 69‒70). -

Katie Wetzel MA Thesis Final SP12

DOMESTIC TRAUMA AND COLONIAL GUILT: A STUDY OF SLOW VIOLENCE IN DOMBEY AND SON AND BLEAK HOUSE BY KATHERINE E. WETZEL Submitted to the graduate degree program in English and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. _____________________________ Chairperson Dr. Dorice Elliott _____________________________ Dr. Anna Neill _____________________________ Dr. Paul Outka Date Defended: April 3, 2012 ii The Thesis Committee for Katherine E. Wetzel certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: DOMESTIC TRAUMA AND COLONIAL GUILT: A STUDY OF SLOW VIOLENCE IN DOMBEY AND SON AND BLEAK HOUSE _______________________________ Chairperson Dr. Dorice Elliott Date Approved: April 3, 2012 iii Abstract In this study of Charles Dickens’s Dombey and Son and Bleak House, I examine the two forms of violence that occur within the homes: slow violence through the naturalized practices of the everyday and immediate forms of violence. I argue that these novels prioritize the immediate forms of violence and trauma within the home and the intimate spaces of the family in order to avoid the colonial anxiety and guilt that is embedded in the naturalized practices of the everyday. For this I utilize Rob Nixon’s theory on slow violence, which posits that some practices and objects that occur as part of the everyday possess the potential to be just as violent as immediate forms of violence. Additionally, the British empire’s presence within the home makes the home a dark and violent place. Dombey and Son does this by displacing colonial anxiety, such as Mr. -

Domestic Trauma and Imperial Pessimism: the Crisis at Home in Charles Dickens’S Dombey and Son

CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture ISSN 1481-4374 Purdue University Press ©Purdue University Volume 21 (2019) Issue 5 Article 13 Domestic Trauma and Imperial Pessimism: The Crisis at Home in Charles Dickens’s Dombey and Son Katherine E. Ostdiek University of Iowa Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/clcweb Part of the American Studies Commons, Comparative Literature Commons, Education Commons, European Languages and Societies Commons, Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Other Arts and Humanities Commons, Other Film and Media Studies Commons, Reading and Language Commons, Rhetoric and Composition Commons, Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons, Television Commons, and the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Dedicated to the dissemination of scholarly and professional information, Purdue University Press selects, develops, and distributes quality resources in several key subject areas for which its parent university is famous, including business, technology, health, veterinary medicine, and other selected disciplines in the humanities and sciences. CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture, the peer-reviewed, full-text, and open-access learned journal in the humanities and social sciences, publishes new scholarship following tenets of the discipline of comparative literature and the field of cultural studies designated as "comparative cultural studies." Publications in the journal are indexed in the Annual Bibliography of English Language and Literature (Chadwyck-Healey), the Arts and Humanities Citation Index (Thomson Reuters ISI), the Humanities Index (Wilson), Humanities International Complete (EBSCO), the International Bibliography of the Modern Language Association of America, and Scopus (Elsevier). The journal is affiliated with the Purdue University Press monograph series of Books in Comparative Cultural Studies. -

Hard Times Major Characters Mr. Gradgrind: Thomas Gradgrind Is the Notorious School Board Superintendent in Dickens's Novel Hard

University of Tikrit College Education for Women Majeed Hammadi Kahalifa Class: Third Class English Department Assistant Lecturer Subj: Novel Hard Times Major characters Mr. Gradgrind: Thomas Gradgrind is the notorious school board Superintendent in Dickens's novel Hard Times who is dedicated to the pursuit of profitable enterprise. His name is now used generically to refer to someone who is hard and only concerned with cold facts and numbers. He is an intense follower of Utilitarian ideas. He soon sees the error of these beliefs however, when his children's lives fall into disarray. Mr. Bounderby: Josiah Bounderby is a business associate of Mr. Gradgrind. Given to boasting about being a self-made man, he employs many of the other central characters of the novel. He has risen to a position of power and wealth from humble origins (though not as humble as he claims). He marries Mr. Gradgrind's daughter Louisa, some 30 years his junior, in what turns out to be a loveless marriage. They have no children. Bounderby is callous, self-centred and ultimately revealed to be a liar and fraud. Louisa: Louisa (Loo) Gradgrind, later Louisa Bounderby, is the eldest child of the Gradgrind family. She has been taught to suppress her feelings and finds it hard to express herself clearly, saying as a child that she has "unmanageable thoughts." After her unhappy marriage, she is tempted to adultery by James Harthouse, but resists him and returns to her father. Her rejection of Harthouse leads to a new understanding of life and of the value of emotions and the imagination. -

The Treatment of Children in the Novels of Charles

THE TREATMENT OF CHILDREN IN THE NOVELS OF CHARLES DICKENS A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF ATLANTA UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS BY CLEOPATRA JONES DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH ATLANTA, GEORGIA AUGUST 1948 ? C? TABLE OF CONTENTS % Pag® PREFACE ii CHAPTER I. REASONS FOR DICKENS' INTEREST IN CHILDREN ....... 1 II. TYPES OF CHILDREN IN DICKENS' NOVELS 10 III. THE FUNCTION OF CHILDREN IN DICKENS' NOVELS 20 IV. DICKENS' ART IN HIS TREATMENT OF CHILDREN 33 SUMMARY 46 BIBLIOGRAPHY 48 PREFACE The status of children in society has not always been high. With the exception of a few English novels, notably those of Fielding, child¬ ren did not play a major role in fiction until Dickens' time. Until the emergence of the Industrial Revolution an unusual emphasis had not been placed on the status of children, and the emphasis that followed was largely a result of the insecure and often lamentable position of child¬ ren in the new machine age. Since Dickens wrote his novels during this period of the nineteenth century and was a pioneer in the employment of children in fiction, these facts alone make a study of his treatment of children an important one. While a great deal has been written on the life and works of Charles Dickens, as far as the writer knows, no intensive study has been made of the treatment of children in his novels. All attempts have been limited to chapters, or more accurately, to generalized statements in relation to his life and works. -

A Christmas Carol Adapted for the Stage by Geoff Elliott Directed by Julia Rodriguez-Elliott and Geoff Elliott December 2–23, 2021 Edu

A NOISE WITHIN HOLIDAY 2021 AUDIENCE GUIDE Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol Adapted for the stage by Geoff Elliott Directed by Julia Rodriguez-Elliott and Geoff Elliott December 2–23, 2021 Edu Pictured: Geoff Elliott and Deborah Strang. Photo by Craig Schwartz. TABLE OF CONTENTS Character Map ......................................3 Synopsis ...........................................4 Quotes from A Christmas Carol .........................5 About the Author Charles Dickens ......................6 Dickensian Timeline: Important Events in Dickens’ Life and Around the World ....8 Dickens’ Times: Victorian London .......................9 Poverty: Life & Death ................................12 Currency & Wealth. .16 About: Scenic Design. .18 About: Costume Design. .19 A Christmas Carol: Overall Design Concept ..............20 Additional Resources . .21 About A Noise Within. 22 A NOISE WITHIN’S EDUCATION PROGRAMS MADE POSSIBLE IN PART BY: Ann Peppers Foundation The Green Foundation Capital Group Companies Kenneth T. and Michael J. Connell Foundation Eileen L. Norris Foundation The Dick and Sally Roberts Ralph M. Parsons Foundation Coyote Foundation Steinmetz Foundation The Jewish Community Dwight Stuart Youth Fund Foundation 3 A NOISE WITHIN 2021/22 SEASON | Holiday 2021 Audience Guide A Christmas Carol CHARACTER MAP CHRISTMAS PAST CHRISTMAS PRESENT CHRISTMAS YET TO COME EBENEZER SCROOGE The protagonist: a bitter old creditor who does not believe in the spirit of Christmas, nor does he possess any sympathy for the poor. JACOB MARLEY GHOST OF CHRISTMAS GHOST OF CHRISTMAS “Dead to begin with.” PRESENT YET TO COME Ebenezer Scrooge’s former A lively spirit who spreads Scrooge fears this ghost’s business partner, who died seven Christmas cheer. premonitions. years prior. His ghost appears before Scrooge on Christmas Eve to warn of him of the Three Spirits, and urges him to choose a FRED OLD JOE, MRS. -

Hard Times by Charles Dickens BOOK the FIRST

Hard Times by Charles Dickens BOOK THE FIRST - SOWING CHAPTER I - THE ONE THING NEEDFUL 'NOW, what I want is, Facts. Teach these boys and girls nothing but Facts. Facts alone are wanted in life. Plant nothing else, and root out everything else. You can only form the minds of reasoning animals upon Facts: nothing else will ever be of any service to them. This is the principle on which I bring up my own children, and this is the principle on which I bring up these children. Stick to Facts, sir!' The scene was a plain, bare, monotonous vault of a school-room, and the speaker's square forefinger emphasized his observations by underscoring every sentence with a line on the schoolmaster's sleeve. The emphasis was helped by the speaker's square wall of a forehead, which had his eyebrows for its base, while his eyes found commodious cellarage in two dark caves, overshadowed by the wall. The emphasis was helped by the speaker's mouth, which was wide, thin, and hard set. The emphasis was helped by the speaker's voice, which was inflexible, dry, and dictatorial. The emphasis was helped by the speaker's hair, which bristled on the skirts of his bald head, a plantation of firs to keep the wind from its shining surface, all covered with knobs, like the crust of a plum pie, as if the head had scarcely warehouse-room for the hard facts stored inside. The speaker's obstinate carriage, square coat, square legs, square shoulders, - nay, his very neckcloth, trained to take him by the throat with an unaccommodating grasp, like a stubborn fact, as it was, - all helped the emphasis. -

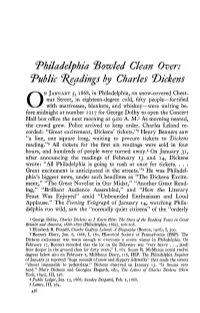

Readings by Charles 'Dickens

Philadelphia ^Bowled Clean Over: Public "Readings by Charles 'Dickens N JANUARY 5, 1868, in Philadelphia, on snow-covered Chest- nut Street, in eighteen-degree cold, fifty people—fortified O with mattresses, blankets, and whiskey—were waiting be- fore midnight at number 1217 for George Dolby to open the Concert Hall box office the next morning at 9:00 A. M.1 As morning neared, the crowd grew. Police arrived to keep order. Charles Leland re- corded: "Great excitement, Dickens' tickets."2 Henry Benners saw "a line, one square long, waiting to procure tickets to T)ickens reading."3 All tickets for the first six readings were sold in four hours, and hundreds of people were turned away.4 On January 31, after announcing the readings of February 13 and 14, Dickens wrote: "All Philadelphia is going to rush at once for tickets. Great excitement is anticipated in the streets."5 He was Philadel- phia's biggest news, under such headlines as "The Dickens Excite- ment," "The Great Novelist in Our Midst," "Another Great Read- Ing," "Brilliant Audience Assembled," and "How the Literary Feast Was Enjoyed" amid "Unbounded Enthusiasm and Loud Applause." The Evening "Telegraph of January 14, watching Phila- delphia run wild, saw the "normally quiet citizens" of the "orderly 1 George Dolby, Charles Dickens as I Knew Him: The Story of the Reading Tours in Great Britain and America, 1866-1870 (Philadelphia, 1885), 206-208. 2 Elizabeth R. Pennell, Charles Godfrey Leland: A Biography (Boston, 1906), I, 300. 3 Benners Diary, Jan. 6, 1868, I, 180, Historical Society of Pennsylvania (HSP).