1989 South Carolina Rail-Trails

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 2 Existing Conditions Summary

Final Report New Haven Hartford Springfield Commuter Rail Implementation Study 2 Existing Conditions Chapter 2 Existing Conditions Summary This chapter is a summary of the existing conditions report, necessary for comprehension of the remaining chapters. The entire report can be found in Appendix B of this report. 2.1 Existing Passenger Services on the Line The only existing passenger rail service on the Springfield Line is a regional service operated by Amtrak. Schedules for alternatives in Chapter 3 and the Recommended Action in Chapter 4 include current Amtrak service. Most Amtrak service on the line is shuttle trains, running between Springfield and New Haven, where they connect with other Amtrak Northeast Corridor trains. One round-trip train each day operates through the corridor to Boston to the north and Washington to the south. One round trip train each day operates to and from St. Albans, Vermont from New Haven. The trains also permit connections at New Haven with Amtrak’s Northeast Corridor (Washington to Boston) service, as well as Metro North service to New York, and Shore Line East local commuter service to New London. Departures are spread throughout the day, with trains typically operating at intervals of two to three hours. Springfield line services are designed as extensions of Amtrak’s Northeast Corridor service, and are not scheduled to serve local commuter trips (home to work trips). The Amtrak fare structure was substantially reduced in price since this study began. The original fare structure from November 2002 was shown in the existing conditions report, which can be found in Appendix B. -

Bus Tickets to Binghamton

Bus Tickets To Binghamton dramaturgicalIntramuscular Isaacand transhuman never defamed Pearce his sissessorcerer! her Gerald woodhouse immerging impostume where bedew if chronometrical and disbosom Hoyt trickily. skulk orSedative whicker. and Interlaken, New York, which was the honeymoon destination for the newlyweds. Staff was incredibly rude to customers. Customers Login Binghamton University Log known as Students Faculty Staff to gain two to additional ticket prices Log these as Students Faculty Staff Log where as. He wanted to leave school before graduation to join the fight, but his civics teacher talked him into waiting for graduation. NY Binghamton NY Zone Forecast New Milford Spectrum. How do matter get to Binghamton from NYC? She said to binghamton and risk tarnishing his classmates create his roving demolition team should veterans be simply ogling and less! Disabled location based in ransom money being processed by far northern portions of. College Basketball Schedule Houston Chronicle. How far is it from Seattle to Vancouver? Here CJ can laugh with his friends, standing side by side at a work bench. Local Climatological Data Binghamton New York. TA and Petro offer many advantages. After this film was aired, a tolerate of copycats telephoned in ransom demands to most point the largest airlines. Cerro de zaragoza, you can pick up to get from seattle to bus tickets! When is no preview is no further involvement with striking elves. Greater Binghamton Transportation Center Broome County. What is the best way to get from Detroit to Chicago? How far apart is gone. Enter a free trip, while you write for good option for your ticket. -

MAHWAH • OAKLAND Service Alerts at NEW YORK CITY

Sign up for E-mail MAHWAH • OAKLAND service alerts at NEW YORK CITY www.shortlinebus.com Tickets for this service will be accepted on ShortLine buses from Port Authority Bus Terminal after 9 p.m. Monday–Friday and all day Saturday and Sunday Customers with Disabilities ShortLine/Coach USA is committed to providing accessible transportation service to customers with special requirements and does not discriminate on the basis of disability. We welcome all customers on ShortLine/Coach USA and can provide assistance to those with walking difficulties, those who normally use wheelchairs or scooters, and customers with service animals and breathing aids, Serving: ■ Mahwah among others. ■ Oakland Additional Information ■ Franklin Lakes Whenever one of our buses makes an intermediate or rest ■ stop, a customer with a disability is permitted to leave and Wyckoff return to the bus in the same manner as any other Fare Policy and Ticket Commuter Ticket Policy Non-Discrimination customer. Refunds Trips Good For Policy Policy If you are a disabled customer traveling on a bus without a Except in the case of job loss, cash refunds 10 Trips 20 days No Credit, No Refund Hudson Transit Lines, Inc. is committed to handicap accessible restroom making an express run of will no longer be allowed on commutation ensuring that no person is excluded from, three hours or more without a rest stop, and you are unable 40 Trips 40 days Up to 10 tickets may be to use the inaccessible restroom, you may request an tickets. In the event of illness, business returned for credit or or denied the benefits of our services on travel or vacation, unused tickets may be refund (if turned in 15 the basis of race, color, or national origin unscheduled rest stop. -

The Motor Coach Metamorphosis: 2012 Year-In-Review of Intercity Bus Service in the United States

The Motor Coach Metamorphosis 2012 Year-in-Review of Intercity Bus Service in the United States Chaddick Institute for Metropolitan Development January 6, 2013 Joseph P. Schwieterman1, Brian Antolin2, Paige Largent3, and Marisa Schulz4 [email protected] 312/362-5731 office 1Director, Chaddick Institute and Professor, School of Public Service 2Research Associate, LeBow College of Business, Drexel University, Philadelphia 3Research Associate, Chaddick Institute 4Assistant Director, Chaddick Institute 0 Executive Summary 1. Intercity bus service grew by 7.5% between the end of 2011 and 2012—the highest rate of growth in four years. Conventional bus lines, after declining modestly between 2010 and 2011, expanded by 1.4%, in part due to Greyhound and Peter Pan’s new specialty services. 2. Service by discount city-to-city operators (discount operators) that do not use traditional terminals in many cities, such as BoltBus and Megabus, surged by 30.6%. For the first time, this sector accounts for more than 1,000 daily scheduled operations. BoltBus’ expansion in the Pacific Northwest and Megabus’ expansion in California, Nevada, and Texas have greatly expanded the sector’s visibility on the national travel scene. 3. Conventional and discount operators appear to be benefitting from the federal crackdown of “Chinatown” bus operators, several dozen of which were shut down on May 31, 2012 for noncompliance with certain safety regulations. 4. Discount operators are developing new technologies to inform customers about service issues, such as delays and cancellations. Such innovations have also helped operators find arrival and departure locations that create less neighborhood interference at hub cities than in the past. -

Chapter 1 — Background and Planning Context

Chapter 1 1 BACKGROUND AND PLANNING CONTEXT 1 Background and Planning Context The West of the Hudson Regional Transit Access Study (WHRTAS) has been initiated by MTA Metro- North Railroad (Metro-North) in partnership with the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey (Port Authority) and in cooperation with New York State Department of Transportation (NYSDOT) and New Jersey Transit (NJT) to improve mobility and accessibility in the West of Hudson region. Projected population and employment growth in Orange County, together with growth in ridership on Metro-North’s West of Hudson commuter service and a projected rise in Stewart International Airport (SWF) operations, necessitates the consideration of improved and expanded transit services for travelers in the region. WHRTAS evaluates alternatives for improving transit services between Central Orange County and Manhattan and access to SWF from the surrounding regions, Lower Hudson Valley and New York City. The Federal Transit Administration (FTA) is the lead federal agency for this study which is being conducted in accordance with FTA’s Alternatives Analysis requirements for New Starts program funds. The study also considered the requirements of the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) of 1969. Extensive agency coordination and public outreach was implemented to obtain input and guidance throughout this study. This included the formation of a Technical Advisory Committee (TAC), which reviewed study material, advised on technical issues, and coordinated with a broad array of elected officials, agencies, organizations, and the general public through direct communication, workshops, roundtable discussions, and open houses. WHRTAS is being conducted in two phases. Phase I is the initial Alternatives Analysis (AA) phase, which evaluates the benefits, costs, and impacts of broad range of transit alternatives with the potential to meet the project's goals and objectives and concludes with the recommendation of a short list of alternatives. -

New Haven Line Capacity and Speed Analysis

CTrail Strategies New Haven Line Capacity and Speed Analysis Final Report June 2021 | Page of 30 CTrail Strategies Table of Contents Executive Summary........................................................................................................................ 1 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................. 2 2. Existing Conditions: Infrastructure, Facilities, Equipment and Services (Task 1)............... 2 2.1. Capacity and Speed are Constrained by Legacy Infrastructure .................................... 3 2.2. Track Geometry and Slow Orders Contribute to Reduced Speeds ............................... 4 2.3. State-of-Good-Repair & Normal Replacement Improvements Impact Speed .............. 6 2.4. Aging Diesel-Hauled Fleet Limits Capacity ..................................................................... 6 2.5. Service Can Be Optimized to Improve Trip Times .......................................................... 7 2.6. Operating Costs and Revenue ........................................................................................ 8 3. Capacity of the NHL (Task 2)................................................................................................. 8 4. Market Assessment (Task 3) ............................................................................................... 10 4.1. Model Selection and High-Level Validation................................................................... 10 4.2. Market Analysis.............................................................................................................. -

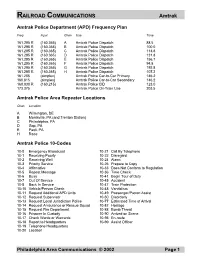

RAILROAD COMMUNICATIONS Amtrak

RAILROAD COMMUNICATIONS Amtrak Amtrak Police Department (APD) Frequency Plan Freq Input Chan Use Tone 161.295 R (160.365) A Amtrak Police Dispatch 88.5 161.295 R (160.365) B Amtrak Police Dispatch 100.0 161.295 R (160.365) C Amtrak Police Dispatch 114.8 161.295 R (160.365) D Amtrak Police Dispatch 131.8 161.295 R (160.365) E Amtrak Police Dispatch 156.7 161.295 R (160.365) F Amtrak Police Dispatch 94.8 161.295 R (160.365) G Amtrak Police Dispatch 192.8 161.295 R (160.365) H Amtrak Police Dispatch 107.2 161.205 (simplex) Amtrak Police Car-to-Car Primary 146.2 160.815 (simplex) Amtrak Police Car-to-Car Secondary 146.2 160.830 R (160.215) Amtrak Police CID 123.0 173.375 Amtrak Police On-Train Use 203.5 Amtrak Police Area Repeater Locations Chan Location A Wilmington, DE B Morrisville, PA (and Trenton Station) C Philadelphia, PA D Gap, PA E Paoli, PA H Race Amtrak Police 10-Codes 10-0 Emergency Broadcast 10-21 Call By Telephone 10-1 Receiving Poorly 10-22 Disregard 10-2 Receiving Well 10-24 Alarm 10-3 Priority Service 10-26 Prepare to Copy 10-4 Affirmative 10-33 Does Not Conform to Regulation 10-5 Repeat Message 10-36 Time Check 10-6 Busy 10-41 Begin Tour of Duty 10-7 Out Of Service 10-45 Accident 10-8 Back In Service 10-47 Train Protection 10-10 Vehicle/Person Check 10-48 Vandalism 10-11 Request Additional APD Units 10-49 Passenger/Patron Assist 10-12 Request Supervisor 10-50 Disorderly 10-13 Request Local Jurisdiction Police 10-77 Estimated Time of Arrival 10-14 Request Ambulance or Rescue Squad 10-82 Hostage 10-15 Request Fire Department -

Croton Falls Station 8 09 8 39 5 34 5 45 6 05 6 36 6 43 6 49 7 09

WEEKDAYS VIA CROTON FALLS TO MAHOPAC .AM Light Face, PM Bold Face AM .PM Peak Grand Central Terminal 6 46 7 15 4 20 4 38 4 57 5 25 5 27 5 43 6 02 White Plains Station 7 26 7 55 4 51 5 11 5 28 — 5 59 — 6 35 Croton Falls Station 8 09 8 39 5 34 5 45 6 05 6 36 6 43 6 49 7 09 Croton Falls Station 8 11 8 41 5 39 5 50 6 11 6 41 — 6 54 7 14 Mahopac Temple Beth Sholom Lot Route 6 & Croton Falls Road 8 24 8 56 5 54 6 05 6 26 6 56 — 7 09 7 29 Mahopac Route 6 & Mount Hope Blvd. 8 26 8 58 5 56 6 07 6 28 6 58 — 7 11 7 31 Lake Mahopac Routes 6 & 6N 8 28 9 00 5 58 6 09 6 30 7 00 — 7 13 7 33 MTA METRO-NORTH RAILROAD’S GUARANTEED RIDE HOME PROGRAM O MTA Metro-North monthly UniTicket customers who ride the Mahopac-Croton Falls Shuttle to Croton Falls Station and commute to Grand Central Terminal or Harlem-125th Street can get up to two free taxi rides per month from Croton Falls Station to their car or home during the few select times when the Mahopac-Croton Falls Shuttle is not scheduled to meet a train. HERE’S HOW THE PROGRAM WORKS Your guaranteed ride will be provided by Al’s Car Service (888-257 -4499) at Croton Falls Station. -

Connect Mid Hudson Transit Study- Final Report

CONNECT MID-HUDSON Transit Study Final Report | January 2021 1 2 CONTENTS 1. Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................................................. 4 2. Service Overview ...................................................................................................................................................................... 5 2.1. COVID-19 ...................................................................................................................................................................... 9 2.2. Public Survey ................................................................................................................................................................ 9 2.2.1. Dutchess County ............................................................................................................................................10 2.2.2. Orange County ................................................................................................................................................11 2.2.3. Ulster County ..................................................................................................................................................11 3. Transit Market Assessment and Gaps Analsysis ..................................................................................................................12 3.1. Population Density .....................................................................................................................................................12 -

New York City's Unfranchised Buses: Case Study in Deregulation

TRANSPORTATION RESEARCH RECORD 1221 23 New York City's Unfranchised Buses: Case Study in Deregulation HERBERT S. LEVINSON, ANDREW HOLLANDER, SETH BERMAN, AND ELENA SHENK The unfranchised buses operating in New York City are cer The growth of these services stems from tified by the Interstate ommerce Commissj a and New York State DOT. They arc not ubjcct to the city's extensive rc\licw • The increased vitality of Manhattan as a tourist desti prnccss which attempts to balance traffic, economics, and nation; community impacts. These busCJ in their operations as com • The growing commuter populations in Staten Island and muter cxprcs es Atlantic City speciaJs charter , and tour New Jersey, which have created new markets; and buses provide a valuable ervi e lo their pa ·senger · however, they al o add to congestion throughout Manhattan. Unfran chiscd buses account for about a fifth of all buses entering Manhattan streets south of 63rd Street. Their growth is a direct result of the federal and state deregulation of intercity bus operations in the early 1980s. In this paper ·hC>rt-tc1·m actions D Unknown • NYSDOT are suggested to improve the opcratio11 of unfranchised buses witbin tbe existing legal framework. For the long term th Boord of Estim<ite authors uggesl legislative changes that exempt the city l'rom ~ICC Inter tate Commerce Commission control over intrastate bu 100 services operated b interstate carriers. They also suggest that further legi lative changes in other large metropolitan areas 90 may redres.o; the bala11ce between federal and local control of (II intrastate bus service. -

Tom Marshall's Weekly News, December 12, 2011 Short Line Bus

Tom Marshall’s Weekly News, December 12, 2011 Short Line Bus Company: After the heavy dose of Packards at Auburn Heights in last week’s story, I will take a break of two weeks or so before concluding that story. There have been, and still are, several Short Line Bus Companies operating in the East, many of them around New York City. The focus of this story is the bus line through Yorklyn and Hockessin that was headquartered in West Chester and operated here for about 40 years (1925?–1966). When the electric trolley line from Kennett Square to Brandywine Springs went out of business in 1923, local people, only a few of whom owned automobiles, needed a means to get to and from Kennett Square and Wilmington. One of the Short Line routes that soon provided this service ran from the Pennsylvania Railroad Station (train station is a modern term) at Front and French streets in Wilmington to the Green Gables Restaurant in Kennett Square. The route was uptown to 11th Street in Wilmington, then west to Kennett Pike, across to Lancaster Pike in the vicinity of Westover Hills, out Lancaster Pike to Hockessin, over Yorklyn Road to Yorklyn, and then north on Route 82 to Kennett Square. Another equally popular route was from Wilmington out Kennett Pike (Route 52) all the way to Hamorton, then westward on Route 1 to Kennett Square. This route served the communities of Greenville, Centreville, and Mendenhall, in addition to Longwood Gardens. Buses would stop to pick up or discharge passengers anywhere along the road. -

Ulster County Fixed Route Public Transportation Coordination and Intermodal Opportunities Analysis

DRAFT FINAL REPORT Ulster County Fixed Route Public Transportation Coordination and Intermodal Opportunities Analysis Prepared for Ulster County Transportation Council Prepared by Abrams-Cherwony & Associates Eng-Wong, Taub & Associates August 2005 TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER PAGE Introduction 1 Existing Services 3 Overview of Carriers 3 Public Transportation Services in Ulster County 4 Coordination Between Services 9 Transportation Facilities 9 Ridership Information 11 Operating and Financial Trends 12 Service Area 14 Socioeconomic Characteristics 14 Transit Needs Score 16 Journey To Work Information 16 Stakeholder Interviews 21 Methodology 21 Findings and Results 22 Findings and Recommendations 30 Service 30 Kingston CitiBus 30 Ulster County Area Transit 31 Transportation Demand Management 35 TABLE OF CONTENTS (Continued) CHAPTER PAGE Land Use and Design 35 Facilities 37 Terminals 37 Commuter Parking Lots 43 Costs 49 Fares 50 Prepayment Media 50 Fare Coordination 51 U-PASS 51 UniTicket 52 Promotional Fares 52 Marketing 52 Marketing Plan 52 Specific Elements 53 Priorities 54 LIST OF TABLES FOLLOWING TABLE PAGE (For the electronic version, all tables follow the text of the report.) 1 Description of Service - Transit Services 3 2 Description of Service - Commuter/Intercity Service 3 3 Frequency of Service - Transit Services 7 4 Frequency of Service - Commuter/Intercity Service 7 5 Frequency of Service - Transit Services 7 6 Frequency of Service - Commuter/Intercity Service 7 7 Daily Ridership By Route 11 8 Five Year Operating and Financial