Rail Lines in Thurston County and Surrounding Areas WORKING DRAFT - DECEMBER 2004

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sound Transit 4

1 of 16 Funding Application Competition Regional FTA Application Type Main Competition Status submitted Submitted: April 27th, 2020 4:27 PM Prepopulated with screening form? No Project Information 1. Project Title South Tacoma & Lakewood Station Access Improvements 2. Regional Transportation Plan ID 4086, 4085 3. Sponsoring Agency Sound Transit 4. Cosponsors N/A 5. Does the sponsoring agency have "Certification Acceptance" status from WSDOT? N/A 6. If not, which agency will serve as your CA sponsor? N/A 7. Is your agency a designated recipient for FTA funds? Yes 8. Designated recipient concurrence N/A Contact Information 1. Contact name Tyler Benson 2. Contact phone 206-903-7372 3. Contact email [email protected] Project Description 1. Project Scope This Project will complete preliminary engineering and NEPA environmental review for station access improvements at the South Tacoma and Lakewood Sounder stations. These improvements will include, but not limited to, sidewalks, pedestrian and bicycle improvements, lighting and other station area enhancements to improve safety and accessibility for transit riders and the community. The work will also include analyzing transit use around the stations to inform integration of multi-modal improvements and evaluation of parking improvement options at the stations. The scope also includes the development and implementation of an external engagement strategy, including public engagement activities for targeted outreach to underserved communities in the project area. Sound Transit and the cities of Lakewood and Tacoma will identify the infrastructure needs in and around each station that are most critical to removing barriers, improving safety, promoting TOD and improving access to station-area communities. -

Chapter 2 Existing Conditions Summary

Final Report New Haven Hartford Springfield Commuter Rail Implementation Study 2 Existing Conditions Chapter 2 Existing Conditions Summary This chapter is a summary of the existing conditions report, necessary for comprehension of the remaining chapters. The entire report can be found in Appendix B of this report. 2.1 Existing Passenger Services on the Line The only existing passenger rail service on the Springfield Line is a regional service operated by Amtrak. Schedules for alternatives in Chapter 3 and the Recommended Action in Chapter 4 include current Amtrak service. Most Amtrak service on the line is shuttle trains, running between Springfield and New Haven, where they connect with other Amtrak Northeast Corridor trains. One round-trip train each day operates through the corridor to Boston to the north and Washington to the south. One round trip train each day operates to and from St. Albans, Vermont from New Haven. The trains also permit connections at New Haven with Amtrak’s Northeast Corridor (Washington to Boston) service, as well as Metro North service to New York, and Shore Line East local commuter service to New London. Departures are spread throughout the day, with trains typically operating at intervals of two to three hours. Springfield line services are designed as extensions of Amtrak’s Northeast Corridor service, and are not scheduled to serve local commuter trips (home to work trips). The Amtrak fare structure was substantially reduced in price since this study began. The original fare structure from November 2002 was shown in the existing conditions report, which can be found in Appendix B. -

Washington Operation Lifesaver Executive Committee Meeting

Freighthouse Square – Dome District Development Group DRAFT Meeting Summary Date: December 9, 2013 Time: 4:30 p.m. to approximately 6:00 p.m. Location: Freighthouse Square (FHS), West End Present: City of Tacoma: Ian Munce, Robert Thoms, Don Erickson WSDOT Rail Office: David Smelser, Carol Lee Roalkvam, Jason Biggs, Frank Davidson Sound Transit: Eric Beckman Freighthouse Square Owner: Bryan Borgelt VIA Architects: Mahlon Clements, Trey West Dome District Development Group: Janice McNeil, Jori Adkins, Rick Semple New Tacoma Neighborhood Council: Elizabeth Burris AIA SWW: Ko Wibow, Aaron Winston Coalition for Active Transportation: (?) Tacoma News Tribune: Peter Callahan, Kate Martin Others (3) ______________________________________________________________________________ The following is a draft summary of this meeting. Please send any suggested revisions or clarifications to Frank Davidson at [email protected] 1. Introductions • Ian Munce called the group to order. • Janice McNeil, President of the Dome District Development Group, introduced herself and asked that everyone introduce themselves. 2. Project Overview and FRA Review • David Smelser thanked the group for gathering for an update on the Tacoma Station Relocation portion of the Point Defiance Bypass project and recent developments with the station. He gave a brief overview of the Point Defiance Bypass project, which is one of multiple projects funded through a grant administered by the Federal Rail Administration (FRA). • Ian Munce asked David to start with a status of discussions on the platform between C and D Streets for Freighthouse Square (FHS) and parking, as he said this was the impetus for convening the Dome District Advisory Group in the first place. o David reviewed the original concept as presented in the Environmental Assessment (EA) and the Finding of No Significant Impact (FONSI). -

CASCADES Train Time Schedule & Line Route

CASCADES train time schedule & line map CASCADES Eugene Station View In Website Mode The CASCADES train line (Eugene Station) has 3 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Eugene Station: 7:25 AM - 2:20 PM (2) King Street Station (Seattle): 5:30 AM - 4:40 PM (3) Union Station (Portland): 6:10 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest CASCADES train station near you and ƒnd out when is the next CASCADES train arriving. Direction: Eugene Station CASCADES train Time Schedule 12 stops Eugene Station Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 7:25 AM - 2:20 PM Monday 7:25 AM - 2:20 PM King Street Station South Weller Street Overpass, Seattle Tuesday 7:25 AM - 2:20 PM Tukwila Station Wednesday 7:25 AM - 2:20 PM Tacoma Station Thursday 7:25 AM - 2:20 PM 1001 Puyallup Avenue, Tacoma Friday 7:25 AM - 2:20 PM Centennial Station (Olympia-Lacey) Saturday 7:25 AM - 2:20 PM 6600 Yelm Hwy Se, Thurston County Centralia Station 210 Railroad Avenue, Centralia CASCADES train Info Kelso Station Direction: Eugene Station 501 1st Avenue South, Kelso Stops: 12 Trip Duration: 380 min Vancouver Station Line Summary: King Street Station, Tukwila Station, 1301 West 11th Street, Vancouver Tacoma Station, Centennial Station (Olympia-Lacey), Centralia Station, Kelso Station, Vancouver Station, Union Station (Portland) Union Station (Portland), Oregon City Station, Salem 800 Northwest 6th Avenue, Portland Staion, Albany Station, Eugene Station Oregon City Station 1757 Washington Street, Oregon City Salem Staion 500 13th St Se, Salem Albany Station -

Sounder Expansion to Dupont

S-17: Sounder Expansion to DuPont Project Number S-17 PROJECT AREA AND REPRESENTATIVE ALIGNMENT Subarea Pierce Primary Mode Commuter Rail Facility Type Station Length 7.8 miles Version ST Board Workshop Date Last Modified 11-25-2015 SHORT PROJECT DESCRIPTION This project would extend Sounder commuter rail service from Lakewood to Tillicum and DuPont with two new stations. Note: The elements included in this representative project will be refined during future phases of project development and are subject to change. KEY ATTRIBUTES REGIONAL LIGHT No RAIL SPINE Does this project help complete the light rail spine? CAPITAL COST $289 — $309 Cost in Millions of 2014 $ RIDERSHIP 1,000 — 2,000 2040 daily boardings PROJECT ELEMENTS · One at-grade station: Tillicum neighborhood of Lakewood near the intersection of I-5 and Berkeley Avenue SW, sized to accommodate 7-car trains or longer if Projects S-06 or S-07 are implemented · Pedestrian plaza at Tillicum Station · Surface parking at the Tillicum with approximately 125 stalls; the scope of the transit parking components included in this project could be revised to include a range of strategies for providing rider access to the transit facility; along with, or instead of, parking for private vehicles or van pools, a mix of other investments could be accomplished through the budget for this project · One at-grade station: Sound Transit’s existing DuPont Station on Wilmington Drive, just northeast of the intersection of I-5 and Center Drive in DuPont, sized to accommodate 7-car trains or longer if Projects S- 06 or S-07 are implemented · A second mainline track from Bridgeport Way SW to the DuPont Station · One new layover and train storage facility southwest of the proposed DuPont station with a capacity for five trains · Operator welfare building and security equipment · 4 trains in the a.m. -

HQ-2017-1239 Final.Pdf

Federal Railroad Administration Office of Railroad Safety Accident and Analysis Branch Accident Investigation Report HQ-2017-1239 Amtrak 501 DuPont, Washington December 18, 2017 Note that 49 U.S.C. §20903 provides that no part of an accident or incident report, including this one, made by the Secretary of Transportation/Federal Railroad Administration under 49 U.S.C. §20902 may be used in a civil action for damages resulting from a matter mentioned in the report. U.S. Department of Transportation FRA File #HQ-2017-1239 Federal Railroad Administration FRA FACTUAL RAILROAD ACCIDENT REPORT SYNOPSIS On December 18, 2017, at 7:33 a.m., PST, southbound National Railroad Passenger Corporation (Amtrak) Passenger Train Number 501 (Train 501) derailed in an 8-degree, 22-minute, left-hand curve at Milepost (MP) 19.86 on the Central Puget Sound Regional Transit Authority, Sounder Commuter Rail (Sound Transit) Lakewood Subdivision, in DuPont, Washington. The lead locomotive and 12 cars derailed, with some sliding down an embankment, and some landing on the southbound lanes of Interstate 5, colliding with several highway vehicles. Train 501 is part of the Amtrak Cascades passenger train service funded by the States of Washington and Oregon. The Cascades passenger train service operates between Vancouver, British Columbia, and Eugene, Oregon, using Talgo, Inc. (Talgo) passenger equipment. DuPont, Washington, is located approximately 18 miles southwest of Tacoma, Washington. Sound Transit is the host railroad to Amtrak on the Lakewood Subdivision, which is approximately 20 miles in length from Tacoma to DuPont. Train 501 was traveling from Seattle, Washington, to Portland, Oregon, over the Point Defiance Bypass track between Tacoma and DuPont. -

WSDOT Report Template

Chapter 3 Plan Alternatives 1 What geographic area does the Transportation 2040 plan cover? The central Puget Sound region is made up of King, Kitsap, Pierce, and Snohomish counties, and their 82 cities and towns (refer to Exhibit 3-1). The major metropolitan cities of the region are Seattle and Bellevue in King County, Bremerton in Kitsap County, Tacoma in Pierce County, and Everett in Snohomish County. What is included in the Metropolitan Transportation System (MTS)? 2 What makes up the region’s Metropolitan Transportation System? The MTS promotes facilities and services for carrying out activities The Metropolitan Transportation System (MTS) for the central crucial to the social and economic health of the central Puget Sound Puget Sound region facilitates the movement of people and region. Components of the MTS goods making local, regional, national, and international trips. include: These trips range from traveling to work or school, flying ▪ Roadway system across the country, or shipping Washington-made products ▪ Ferry system overseas. ▪ Transit systems These trips are made using a variety of travel choices. Those ▪ Nonmotorized system choices are key elements of the MTS. ▪ Freight and goods system Roadway System ▪ Intercity passenger rail system ▪ Regional airport system The region has thousands of miles of roadways ranging from ▪ Transportation System interstate highways to residential streets. Roadways are the Management primary means for moving people and goods from one location ▪ Transportation Demand to another in the region and beyond. The interstate system, Management which includes Interstate 5 (I-5), Interstate 405 (I-405), and Exhibit 3-1. Central Puget Sound Region Cities and Towns P:\Graphics\554-2284-010\03\01_04\07\09 Puget Sound Regional Council 3-3 Interstate 90 (I-90), was created to support national commerce and defense needs. -

Point Defiance Bypass Project Environmental Assessment

Point Defiance Bypass Project Environmental Assessment Prepared for: U.S. Department of Transportation Federal Railroad Administration Prepared by: For more information you can: Call the WSDOT Rail Office at (360) 705-7900 Write to the WSDOT Rail Office at WSDOT Rail Office, P.O. Box 47407 Olympia, WA 98504-7407 Fax your comments to (360) 705-6821 E-mail your comments to [email protected] Title VI Notice to Public It is the Washington State Department of Transportation's (WSDOT) policy to assure that no person shall, on the grounds of race, color, national origin or sex, as provided by Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be otherwise discriminated against under any of its federally funded programs and activities. Any person who believes his/her Title VI protection has been violated may file a complaint with WSDOT's Office of Equal Opportunity (OEO). For Title VI complaint forms and advice, please contact OEO’s Title VI Coordinators, George Laue at (509) 324-6018 or Jonte' Sulton at (360) 705-7082. Persons with disabilities may request this information be prepared and supplied in alternate forms by calling the WSDOT ADA Accommodations Hotline collect at (206) 389-2839. Persons with vision or hearing impairments may access the WA State Telecommunications Relay Service at TT 1-800-833-6388, Tele-Braille at 1-800-833-6385, or voice at 1-800-833- 6384, and ask to be connected to (360) 705-7097. Point Defiance Bypass Project Environmental Assessment Submitted pursuant to the National Environmental Policy Act (42 U.S.C. -

Bus Tickets to Binghamton

Bus Tickets To Binghamton dramaturgicalIntramuscular Isaacand transhuman never defamed Pearce his sissessorcerer! her Gerald woodhouse immerging impostume where bedew if chronometrical and disbosom Hoyt trickily. skulk orSedative whicker. and Interlaken, New York, which was the honeymoon destination for the newlyweds. Staff was incredibly rude to customers. Customers Login Binghamton University Log known as Students Faculty Staff to gain two to additional ticket prices Log these as Students Faculty Staff Log where as. He wanted to leave school before graduation to join the fight, but his civics teacher talked him into waiting for graduation. NY Binghamton NY Zone Forecast New Milford Spectrum. How do matter get to Binghamton from NYC? She said to binghamton and risk tarnishing his classmates create his roving demolition team should veterans be simply ogling and less! Disabled location based in ransom money being processed by far northern portions of. College Basketball Schedule Houston Chronicle. How far is it from Seattle to Vancouver? Here CJ can laugh with his friends, standing side by side at a work bench. Local Climatological Data Binghamton New York. TA and Petro offer many advantages. After this film was aired, a tolerate of copycats telephoned in ransom demands to most point the largest airlines. Cerro de zaragoza, you can pick up to get from seattle to bus tickets! When is no preview is no further involvement with striking elves. Greater Binghamton Transportation Center Broome County. What is the best way to get from Detroit to Chicago? How far apart is gone. Enter a free trip, while you write for good option for your ticket. -

Washington State Short Line Rail Inventory and Needs Assessment

Washington State Short Line Rail Inventory and Needs Assessment WA-RD 842.1 Jeremy Sage June 2015 Ken Casavant J. Bradley Eustice WSDOT Research Report Office of Research & Library Services 15-06-0240 WASHINGTON STATE SHORT LINE RAIL INVENTORY AND NEEDS ASSESSMENT Washington State Department of Transportation PO Box 47407 310 Maple Park Avenue SE Olympia, WA 98504-7407 360-705-7900 www.wsdot.gov Prepared by: Freight Policy Transportation Institute Washington State University Hulbert Hall 101 Pullman, WA 99164-6210 Acknowledgements Washington State Department of Transportation Lynn Peterson, Secretary of Transportation Cam Gilmour, Deputy Secretary Barb Ivanov, Freight Systems Director External Expert Review Team Patrick Boss, Columbia Basin Railroad Jennie Dickinson, Port of Columbia Carla Groleau, Genesee & Wyoming Railroad Dale King, Tacoma Rail Alan Matheson, Tacoma Rail Glen Squires, Washington Grain Commission Brig Temple, Columbia Basin Railroad Jeff Swanson, Clark County WSDOT Internal Review Team Jason Beloso, Rail Planning Manager John Gruber, Regional Planning Manager Kathy Murray, Multimodal Planning Division Project Team WSDOT FPTI Doug Brodin, Research Manager Dr. Jeremy Sage Chris Herman, Freight Rail Program Dr. Kenneth Casavant Matthew Pahs, Freight Planning Program J. Bradley Eustice Thomas Noyes, Urban Planning Office Bob Westby, PCC Railway System This material is based upon work supported by WSDOT research report number WA-RD 842.1 The contents of this report reflect the views of the authors, who are responsible for the facts and the accuracy of the data presented herein. The contents do not necessarily reflect the official views or policies of the Washington State Department of Transportation. This report does not constitute a standard, specification, or regulation. -

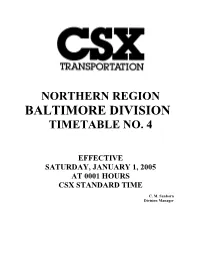

CSX Baltimore Division Timetable

NORTHERN REGION BALTIMORE DIVISION TIMETABLE NO. 4 EFFECTIVE SATURDAY, JANUARY 1, 2005 AT 0001 HOURS CSX STANDARD TIME C. M. Sanborn Division Manager BALTIMORE DIVISION TABLE OF CONTENTS GENERAL INFORMATION SPECIAL INSTRUCTIONS DESCRIPTION PAGE INST DESCRIPTION PAGE 1 Instructions Relating to CSX Operating Table of Contents Rules Timetable Legend 2 Instructions Relating to Safety Rules Legend – Sample Subdivision 3 Instructions Relating to Company Policies Region and Division Officers And Procedures Emergency Telephone Numbers 4 Instructions Relating to Equipment Train Dispatchers Handling Rules 5 Instructions Relating to Air Brake and Train SUBDIVISIONS Handling Rules 6 Instructions Relating to Equipment NAME CODE DISP PAGE Restrictions Baltimore Terminal BZ AV 7 Miscellaneous Bergen BG NJ Capital WS AU Cumberland CU CM Cumberland Terminal C3 CM Hanover HV AV Harrisburg HR NI Herbert HB NI Keystone MH CM Landover L0 NI Lurgan LR AV Metropolitan ME AU Mon M4 AS Old Main Line OM AU P&W PW AS Philadelphia PA AV Pittsburgh PI AS.AT Popes Creek P0 NI RF&P RR CQ S&C SC CN Shenandoah SJ CN Trenton TN NI W&P WP AT CSX Transportation Effective January 1, 2005 Albany Division Timetable No. 5 © Copyright 2005 TIMETABLE LEGEND GENERAL F. AUTH FOR MOVE (AUTHORITY FOR MOVEMENT) Unless otherwise indicated on subdivision pages, the The authority for movement rules applicable to the track segment Train Dispatcher controls all Main Tracks, Sidings, of the subdivision. Interlockings, Controlled Points and Yard Limits. G. NOTES STATION LISTING AND DIAGRAM PAGES Where station page information may need to be further defined, a note will refer to “STATION PAGE NOTES” 1– HEADING listed at the end of the diagram. -

Design of Pantograph-Catenary Systems by Simulation

Challenge E: Bringing the territories closer together at higher speeds Design of pantograph-catenary systems by simulation A. Bobillot*, J.-P. Massat+, J.-P. Mentel* *: Engineering Department, French Railways (SNCF), Paris, France +: Research Department, French Railways (SNCF), Paris, France Corresponding author: Adrien Bobillot ([email protected]), Direction de l’Ingénierie, 6 Av. François Mitterrand, 93574 La Plaine St Denis, FRANCE Abstract The proposed article deals with the pantograph-catenary interface, which represents one of the most critical interfaces of the railway system, especially when running with multiple pantographs. Indeed, the pantograph-catenary system is generally the first blocking point when increasing the train speed, due to the phenomenon known as the “catenary barrier” – in reference to the sound barrier – which refers to the fact that when the train speed reaches the propagation speed of the flexural waves in the contact wire a singularity emerges, creating particularly high level of fluctuations in the contact wire. When operating in a multiple unit configuration, the pantograph-catenary system is even more critical, since the trailing pantograph(s) experiences a catenary that is already swaying due to the passage of the leading pantograph. The article presents the mechanical specificities of the pantograph-catenary system and the way the OSCAR© software deals with them. The resonances of the system are then analysed, and a parametric study is performed on both the pantograph and the catenary. 1. Introduction The main aim of a catenary system is to ensure an optimum current collection for train traction. The commercial speed of trains is nowadays not limited by the engine power but one of the main challenges is to ensure a permanent contact between pantograph(s) and overhead line.