BIO-Annual-Report-1978.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NIHAA Summer 1993

The Newsletter of the NIH Alumni Association Summer 1993 Vol. 5, No . 2 date Nobel Laureate Harold Varmus Nominated as 14th NIH Director Ruth Kirschstein Named Acting Director President Clinton on A ug. 3 announced his intention to nominate Dr. Harold Eliot Varmus as the 14th director of th e National Institutes of Health. A Senate confirmation process must precede Yarmus· taking over leadership of the institutes. Winner of the Nobel Prize in 1989 for his work in cancer research. Va1111us. 53. is a professor of microbi ology. biochemistry. and biophysics. and the American Cancer Society pro fessor vfmoh:cu/ur >1iro/O£)' iJI l/Je Uni versity of California, San Francisco. He is a leader in the stu dy of cancer causing genes called "oncogenes," and an intemationall-y fecogni:z.ed authof\t-y Dr. Ruth l. Kirschsteln , acting NIH director on retroviruses. the viruses that cause Dr. Harold E. Varmus , direclor-designale AIDS and many cancers in animnl.. FIC 25 Years Old In '93 Thirty-eight-year NIH veteran Dr. Research Festival '93 Schedule Ruth Kirschstein. director of NIGM S Scholars-in-Residence (See Director p. 6) NIHAA Members Invited Program Celebrates To Alumni Symposium In This Issue Tile fas\ morning ofNCH Rc:-.c;\rch Nursing cell/er /J1·1·111111•s Festival '93-Monday. Sept. 20-has This year. the Fogarty Intern ational 17th i11s1it11tc• 111 NII/ p. ? been designated National lnsritute of Center (FIC) is 25 years old . T he cen Greeri11gs from 1/,11 1w11• NII /AA prl'sidt'lll. Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Tltolll(IS .I. -

Advertising (PDF)

Neuroscience 2013 SEE YOU IN San Diego November 9 – 13, 2013 Join the Society for Neuroscience Are you an SfN member? Join now and save on annual meeting registration. You’ll also enjoy these member-only benefits: • Abstract submission — only SfN members can submit abstracts for the annual meeting • Lower registration rates and more housing choices for the annual meeting • The Journal of Neuroscience — access The Journal online and receive a discounted subscription on the print version • Free essential color charges for The Journal of Neuroscience manuscripts, when first and last authors are members • Free online access to the European Journal of Neuroscience • Premium services on NeuroJobs, SfN’s online career resource • Member newsletters, including Neuroscience Quarterly and Nexus If you are not a member or let your membership lapse, there’s never been a better time to join or renew. Visit www.sfn.org/joinnow and start receiving your member benefits today. www.sfn.org/joinnow membership_full_page_ad.indd 1 1/25/10 2:27:58 PM The #1 Cited Journal in Neuroscience* Read The Journal of Neuroscience every week to keep up on what’s happening in the field. s4HENUMBERONECITEDJOURNAL INNEUROSCIENCE s4HEMOSTNEUROSCIENCEARTICLES PUBLISHEDEACHYEARNEARLY in 2011 s )MPACTFACTOR s 0UBLISHEDTIMESAYEAR ,EARNMOREABOUTMEMBERAND INSTITUTIONALSUBSCRIPTIONSAT *.EUROSCIORGSUBSCRIPTIONS *ISI Journal Citation Reports, 2011 The Journal of Neuroscience 4HE/FlCIAL*OURNALOFTHE3OCIETYFOR.EUROSCIENCE THE HISTORY OF NEUROSCIENCE IN AUTOBIOGRAPHY THE LIVES AND DISCOVERIES OF EMINENT SENIOR NEUROSCIENTISTS CAPTURED IN AUTOBIOGRAPHICAL BOOKS AND VIDEOS The History of Neuroscience in Autobiography Series Edited by Larry R. Squire Outstanding neuroscientists tell the stories of their scientific work in this fascinating series of autobiographical essays. -

Cold Spring Harbor Symposia on Quantitative Biology

COLD SPRING HARBOR SYMPOSIA ON QUANTITATIVE BIOLOGY VOLUME XL COLD SPRING HARBOR SYMPOSIA 0 N Q UA NTITA T1VE BIOLO G Y Founded in 1933 by REGINALD G. HARRIS Director of the Biological Laboratory 1924 to 1936 Volume I (1933).Surface Phenomena Volume II (1934) Aspects of Growth Volume III (1935) Photochemical Reactions Volume IV (1936) Excitation Phenomena Volume V (1937) Internal Secretions Volume VI (1938) Protein Chemistry Volume VII (1939) Biological Oxidations Volume VIII (1940) Permeability and the Nature of Cell Membranes Volume IX (1941) Genes and Chromosomes: Structure and Organization Volume X (1942) The Relation of Hormones to Development Volume XI (1946) Heredity and Variation in Microorganisms Volume XII (1947) Nucleic Acids and Nucleoproteins Volume XIII (1948) Biological Applications of Tracer Elements Volume XIV (1949) Amino Acids and Proteins Volume XV (1950) Origin and Evolution of Man Volume XVI (1951) Genes and Mutations Volume XVII (1952) The Neuron Volume XVIII (1953) Viruses Volume XIX (1954) The Mammalian Fetus: Physiological Aspects of Development Volume XX (1955) Population Genetics: The Nature and Causes of Genetic Variability in Population Volume XXI (1956) Genetic Mechanisms: Structure and Function Volume XXII (1957) Population Studies: Animal Ecology and Demography Volume XXIII (1958) Exchange of Genetic Material: Mechanism and Consequences Volume XXIV (1959) Genetics and Twentieth Century Darwinism Volume XXV (1960) Biological Clocks Volume XXVI (1961) Cellular Regulatory Mechanisms Volume XXVII (1962) Basic -

Section 1: MIT Facts and History

1 MIT Facts and History Economic Information 9 Technology Licensing Office 9 People 9 Students 10 Undergraduate Students 11 Graduate Students 12 Degrees 13 Alumni 13 Postdoctoral Appointments 14 Faculty and Staff 15 Awards and Honors of Current Faculty and Staff 16 Awards Highlights 17 Fields of Study 18 Research Laboratories, Centers, and Programs 19 Academic and Research Affiliations 20 Education Highlights 23 Research Highlights 26 7 MIT Facts and History The Massachusetts Institute of Technology is one nologies for artificial limbs, and the magnetic core of the world’s preeminent research universities, memory that enabled the development of digital dedicated to advancing knowledge and educating computers. Exciting areas of research and education students in science, technology, and other areas of today include neuroscience and the study of the scholarship that will best serve the nation and the brain and mind, bioengineering, energy, the envi- world. It is known for rigorous academic programs, ronment and sustainable development, informa- cutting-edge research, a diverse campus commu- tion sciences and technology, new media, financial nity, and its long-standing commitment to working technology, and entrepreneurship. with the public and private sectors to bring new knowledge to bear on the world’s great challenges. University research is one of the mainsprings of growth in an economy that is increasingly defined William Barton Rogers, the Institute’s founding pres- by technology. A study released in February 2009 ident, believed that education should be both broad by the Kauffman Foundation estimates that MIT and useful, enabling students to participate in “the graduates had founded 25,800 active companies. -

Sten Grillner

BK-SFN-HON_V9-160105-Grillner.indd 108 5/6/2016 4:11:20 PM Sten Grillner BORN: Stockholm, Sweden June 14, 1941 EDUCATION: University of Göteborg, Sweden, Med. Candidate (1962) University of Göteborg, Sweden, Dr. of Medicine, PhD (1969) Academy of Science, Moscow, Visiting Scientist (1971) APPOINTMENTS: Docent in Physiology, Medical Faculty, University of Göteborg (1969–1975) Professor, Department of Physiology III, Karolinska Institute (1975–1986) Director, Nobel Institute for Neurophysiology, Karolinska Institute, Professor (1987) Nobel Committee for Physiology or Medicine, Chair, 1995–1997 (1987–1998) Nobel Assembly at the Karolinska Institutet, Member Chair, 2005 (1988–2008) Chairman Department of Neuroscience, Karolinska Institutet (1993–2000) Distinguished Professor, Karolinska Institutet (2010) HONORS AND AWARDS: Member of Academiae Europaea 1990– Member of Royal Swedish Academy of Science 1993– Chairman Section for Biology and Member of Academy Board, 2004–2010 Member of Norwegian Academy of Science and Letters, 1997– Member American Academy of Arts and Sciences, 2004– Honorary Member of the Spanish Medical Academy, 2006– Foreign Associate of Institute of Medicine of the National Academy, United States, 2006– Foreign Associate of the National Academy, United States, 2010– Associate of the Neuroscience Institute, La Jolla, 1989– Member EMBO, 2014– Florman Award, Royal Swedish Academy of Science, 1977 Grass Lecturer to the Society of Neuroscience, Boston, 1983 Greater Nordic Prize of Eric Fernstrom, Lund, Sweden, 1990 Bristol-Myers -

2004 Albert Lasker Nomination Form

albert and mary lasker foundation 110 East 42nd Street Suite 1300 New York, ny 10017 November 3, 2003 tel 212 286-0222 fax 212 286-0924 Greetings: www.laskerfoundation.org james w. fordyce On behalf of the Albert and Mary Lasker Foundation, I invite you to submit a nomination Chairman neen hunt, ed.d. for the 2004 Albert Lasker Medical Research Awards. President mrs. anne b. fordyce The Awards will be offered in three categories: Basic Medical Research, Clinical Medical Vice President Research, and Special Achievement in Medical Science. This is the 59th year of these christopher w. brody Treasurer awards. Since the program was first established in 1944, 68 Lasker Laureates have later w. michael brown Secretary won Nobel Prizes. Additional information on previous Lasker Laureates can be found jordan u. gutterman, m.d. online at our web site http://www.laskerfoundation.org. Representative Albert Lasker Medical Research Awards Program Nominations that have been made in previous years may be updated and resubmitted in purnell w. choppin, m.d. accordance with the instructions on page 2 of this nomination booklet. daniel e. koshland, jr., ph.d. mrs. william mccormick blair, jr. the honorable mark o. hatfied Nominations should be received by the Foundation no later than February 2, 2004. Directors Emeritus A distinguished panel of jurors will select the scientists to be honored. The 2004 Albert Lasker Medical Research Awards will be presented at a luncheon ceremony given by the Foundation in New York City on Friday, October 1, 2004. Sincerely, Joseph L. Goldstein, M.D. Chairman, Awards Jury Albert Lasker Medical Research Awards ALBERT LASKER MEDICAL2004 RESEARCH AWARDS PURPOSE AND DESCRIPTION OF THE AWARDS The major purpose of these Awards is to recognize and honor individuals who have made signifi- cant contributions in basic or clinical research in diseases that are the main cause of death and disability. -

Barbara Mcclintock's World

Barbara McClintock’s World Timeline adapted from Dolan DNA Learning Center exhibition 1902-1908 Barbara McClintock is born in Hartford, Connecticut, the third of four children of Sarah and Thomas Henry McClintock, a physician. She spends periods of her childhood in Massachusetts with her paternal aunt and uncle. Barbara at about age five. This prim and proper picture betrays the fact that she was, in fact, a self-reliant tomboy. Barbara’s individualism and self-sufficiency was apparent even in infancy. When Barbara was four months old, her parents changed her birth name, Eleanor, which they considered too delicate and feminine for such a rugged child. In grade school, Barbara persuaded her mother to have matching bloomers (shorts) made for her dresses – so she could more easily join her brother Tom in tree climbing, baseball, volleyball, My father tells me that at the and football. age of five I asked for a set of tools. He My mother used to did not get me the tools that you get for an adult; he put a pillow on the floor and give got me tools that would fit in my hands, and I didn’t me one toy and just leave me there. think they were adequate. Though I didn’t want to tell She said I didn’t cry, didn’t call for him that, they were not the tools I wanted. I wanted anything. real tools not tools for children. 1908-1918 McClintock’s family moves to Brooklyn in 1908, where she attends elementary and secondary school. In 1918, she graduates one semester early from Erasmus Hall High School in Brooklyn. -

I. Hox Genes 2

School ofMedicine Oregon Health Sciences University CERTIFICATE OF APPROVAL This is certify that the Ph.D. thesis of WendyKnosp has been approved Mentor/ Advisor ~ Member Member QUANTITATIVE ANALYSIS OF HOXA13 FUNCTION IN THE DEVELOPING LIMB By Wendy M. lt<nosp A DISSERTATION Presented to the Department of Molecular and Medical Genetics and the Oregon Health & Science University School of Medicine in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2006 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES iv LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS vii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS X ABSTRACT xii CHAPTER 1: Introduction 1 I. Hox genes 2 A. Discovery of Hox genes in Drosophila melanogaster 2 B. Hox cluster colinearity and conservation 7 C. Human Hox mutations 9 D. Hoxa13: HFGS and Guttmacher syndromes 10 II. The Homeodomain 12 A. Homeodomain structure 12 B. DNA binding 14 Ill. Limb development 16 A. Patterning of the limb axes 16 B. Digit formation 20 C. lnterdigital programmed cell death 21 IV. BMPs and limb development 23 A. BMP signaling in the limb 23 B. BMP target genes 27 V. Hoxa13 and embryonic development 30 A. The Hoxa13-GFP mouse model 30 B. Hoxa13 mutant phenotypes 34 C. HOXA 13 homeodomain 35 D. HOXA 13 protein-protein interactions 36 E. HOXA 13 target genes 37 VI. Hypothesis and Rationale 39 CHAPTER 2: HOXA13 regulates Bmp2 and Bmp7 40 I. Abstract 42 II. Introduction 43 Ill. Results 46 IV. Discussion 69 v. Materials and Methods 75 VI. Acknowledgements 83 11 CHAPTER 3: Quantitative analysis of HOXA13 function 84 HOXA 13 regulation of Sostdc1 I. -

The Contributions of George Beadle and Edward Tatum

| PERSPECTIVES Biochemical Genetics and Molecular Biology: The Contributions of George Beadle and Edward Tatum Bernard S. Strauss1 Department of Molecular Genetics and Cell Biology, The University of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois 60637 KEYWORDS George Beadle; Edward Tatum; Boris Ephrussi; gene action; history It will concern us particularly to take note of those cases in Genetics in the Early 1940s which men not only solved a problem but had to alter their mentality in the process, or at least discovered afterwards By the end of the 1930s, geneticists had developed a sophis- that the solution involved a change in their mental approach ticated, self-contained science. In particular, they were able (Butterfield 1962). to predict the patterns of inheritance of a variety of charac- teristics, most morphological in nature, in a variety of or- EVENTY-FIVE years ago, George Beadle and Edward ganisms although the favorites at the time were clearly Tatum published their method for producing nutritional S Drosophila andcorn(Zea mays). These characteristics were mutants in Neurospora crassa. Their study signaled the start of determined by mysterious entities known as “genes,” known a new era in experimental biology, but its significance is to be located at particular positions on the chromosomes. generally misunderstood today. The importance of the work Furthermore, a variety of peculiar patterns of inheritance is usually summarized as providing support for the “one gene– could be accounted for by alteration in chromosome struc- one enzyme” hypothesis, but its major value actually lay both ture and number with predictions as to inheritance pattern in providing a general methodology for the investigation of being quantitative and statistical. -

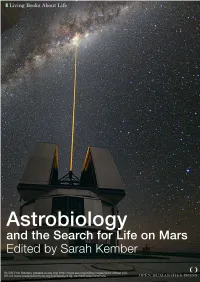

Astrobiology and the Search for Life on Mars Edited by Sarah Kember

Astrobiology and The Search for Life on Mars edited by Sarah Kember Introduction: What Is Life? I’m not going to answer this question. In fact, I doubt if it will ever be possible to give a full answer. (Haldane, 1949: 58) What Is Life? J. B. S. Haldane (1949) and Erwin Schrödinger (1944), two of the twentieth century’s most influential scientists, posed the direct question, ‘what is life?’ and declared that it was a question unlikely to find an answer. Life, they suggested, might exceed the ability of science to represent it and even though the sciences of biology, physics and chemistry might usefully describe life’s structures, systems and processes, those sciences should not seek to reduce it to the sum of its parts. While Schrödinger drew attention to the physical structure of living matter, including especially the cell, Haldane asserted that ‘what is common to life is the chemical events’ (1949: 59) and so therefore life might be defined, though not reduced, to ‘a pattern of chemical processes’ (62) involving the use of oxygen, enzymes and so on. Following Schrödinger and Haldane, Chris McKay’s article, published in 2004 and included in this collection, asks again ‘What is Life – and How Do We Search For It in Other Worlds?’. For him, the still open and unresolved question of life is intrinsically linked to the problem of how to find it (here, or elsewhere) since, he queries, how can we search for something that we cannot adequately define? It should be noted that this dilemma did not deter the founders of Artificial Life, a project that succeeded Artificial Intelligence and that sought to both simulate ‘life-as-we-know-it’ and synthesise ‘life-as-it-could-be’ by reducing life to the informational and therefore computational criteria of self-organisation, self-replication, evolution, autonomy and emergence (Langton, 1996: 40; Kember, 2003). -

Genes, Genomes and Genetic Analysis

© Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION UNIT 1 © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FORDefining SALE OR DISTRIBUTION and WorkingNOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION with Genes © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION Chapter 1 Genes, Genomes, and Genetic Analysis Chapter 2 DNA Structure and Genetic Variation © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION © Molekuul/Science Photo Library/Getty Images. © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC. NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION 9781284136609_CH01_Hartl.indd 1 08/11/17 8:50 am © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC -

Beyond the Big Bang • the Amazon's Lost Civilizations • the Truth

SFI Bulletin winter 2006, vol. 21 #1 Beyond the Big Bang • The Amazon’s Lost Civilizations • The Truth Behind Lying The Bulletin of the Santa Fe Institute is published by SFI to keep its friends and supporters informed about its work. The Santa Fe Institute is a private, independent, multidiscipli- nary research and education center founded in 1984. Since its founding, SFI has devoted itself to creating a new kind of sci- entific research community, pursuing emerging synthesis in science. Operating as a visiting institution, SFI seeks to cat- alyze new collaborative, multidisciplinary research; to break down the barriers between the traditional disciplines; to spread its ideas and methodologies to other institutions; and to encourage the practical application of its results. Published by the Santa Fe Institute 1399 Hyde Park Road Santa Fe, New Mexico 87501, USA phone (505) 984-8800 fax (505) 982-0565 home page: http://www.santafe.edu Note: The SFI Bulletin may be read at the website: www.santafe.edu/sfi/publications/Bulletin/. If you would prefer to read the Bulletin on your computer rather than receive a printed version, contact Patrisia Brunello at 505/984-8800, Ext. 2700 or [email protected]. EDITORIAL STAFF: Ginger Richardson Lesley S. King Andi Sutherland CONTRIBUTORS: Brooke Harrington Janet Yagoda Shagam Julian Smith Janet Stites James Trefil DESIGN & PRODUCTION: Paula Eastwood PHOTO: ROBERT BUELTEMAN ©2004 BUELTEMAN PHOTO: ROBERT SFI Bulletin Winter 2006 TOCtable of contents 3 A Deceptively Simple Formula 2 How Life Began 3 From