Historic Building Appraisals of the 3 New Items

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LC Paper No. CB(1)531/20-21(05)

LC Paper No. CB(1)531/20-21(05) For discussion on 23 February 2021 Legislative Council Panel on Development Progress of Work by the Sustainable Lantau Office (SLO), and Staffing Proposals of SLO, Planning Department and Railway Development Office of Highways Department for Taking Forward and Implementation of Development and Conservation Projects related to Lantau PURPOSE The paper aims to brief members on: (a) the proposal of the Sustainable Lantau Office (SLO) of the Civil Engineering and Development Department (CEDD) to retain four supernumerary directorate posts, and create two supernumerary directorate posts up to 31 March 2025 to provide directorate support for the implementation of new and on-going development and conservation initiatives in Lantau (details at Enclosure 1); (b) the proposal of the Planning Department to create one supernumerary directorate post of Chief Town Planner up to 31 March 2025 to provide high-level steer for various strategic planning tasks for the sustainable development of Lantau (details at Enclosure 2); (c) the proposal of the Railway Development Office of the Highways Department to create one supernumerary directorate post of Chief Engineer up to 31 March 2025 to provide technical support for the planning and implementation of the proposed priority rail links and the possible rail links for the longer term under the “Studies related to Artificial Islands in the Central Waters” (details at Enclosure 3); and (d) the progress of work made by SLO of CEDD (details at Enclosure 4). ADVICE SOUGHT 2. Members are invited to comment on the above staffing proposals1. After soliciting Members’ comments, we intend to submit the proposals to the Establishment Subcommittee for consideration and to the Finance Committee for approval at the soonest opportunity. -

Transport Department Notice

TRANSPORT DEPARTMENT NOTICE Special Traffic and Transport Arrangements on Hong Kong Island for the Public Processions on 1 January 2020 (Wednesday) Notice is hereby given that the following special traffic and transport arrangements will be implemented to facilitate the public processions on Hong Kong Island on 1 January 2020 (Wednesday): I. Special Traffic Arrangements A. Road Closure (i) The following roads will be temporarily closed to all vehicular traffic from about 1.30 pm onwards until the crowd is dispersed and the road closure is lifted: (a) The U-turn slip road leading from Gloucester Road southbound to Gloucester Road northbound underneath Tai Hang Road flyover; (b) Sugar Street; (c) Great George Street (if necessary); (d) The section of Paterson Street between Gloucester Road and Great George Street (if necessary); (e) Kingston Street (if necessary); (f) The section of Gloucester Road southbound between Victoria Park Roadflyover and Causeway Road (if necessary); (g) Cleveland Street (if necessary); (h) Cannon Street (if necessary); (i) The section of Lockhart Road east of Percival Street (if necessary); and (j) The section of Jaffe Road east of Percival Street (if necessary). (ii) The following roads will be temporarily closed to all vehicular traffic from about 1.45 pm onwards until the crowd is dispersed and the road closure is lifted: (a) Jardine’s Bazaar; (b) Tang Lung Street; (c) The section of Canal Road East between Russell Street and Hennessy Road; (d) The section of Canal Road West between Sharp Street West and Hennessy Road; (e) The section of Wan Chai Road between Canal Road West and Morrison Hill Road; and (f) The section of Bowrington Road between Sharp Street West and Hennessy Road. -

List of Buildings with Confirmed / Probable Cases of COVID-19

List of Buildings With Confirmed / Probable Cases of COVID-19 List of Residential Buildings in Which Confirmed / Probable Cases Have Resided (Note: The buildings will remain on the list for 14 days since the reported date.) Related Confirmed / District Building Name Probable Case(s) Islands Hong Kong Skycity Marriott Hotel 5482 Islands Hong Kong Skycity Marriott Hotel 5483 Yau Tsim Mong Block 2, The Long Beach 5484 Kwun Tong Dorsett Kwun Tong, Hong Kong 5486 Wan Chai Victoria Heights, 43A Stubbs Road 5487 Islands Tower 3, The Visionary 5488 Sha Tin Yue Chak House, Yue Tin Court 5492 Islands Hong Kong Skycity Marriott Hotel 5496 Tuen Mun King On House, Shan King Estate 5497 Tuen Mun King On House, Shan King Estate 5498 Kowloon City Sik Man House, Ho Man Tin Estate 5499 Wan Chai 168 Tung Lo Wan Road 5500 Sha Tin Block F, Garden Rivera 5501 Sai Kung Clear Water Bay Apartments 5502 Southern Red Hill Park 5503 Sai Kung Po Lam Estate, Po Tai House 5504 Sha Tin Block F, Garden Rivera 5505 Islands Ying Yat House, Yat Tung Estate 5506 Kwun Tong Block 17, Laguna City 5507 Crowne Plaza Hong Kong Kowloon East Sai Kung 5509 Hotel Eastern Tower 2, Pacific Palisades 5510 Kowloon City Billion Court 5511 Yau Tsim Mong Lee Man Building 5512 Central & Western Tai Fat Building 5513 Wan Chai Malibu Garden 5514 Sai Kung Alto Residences 5515 Wan Chai Chee On Building 5516 Sai Kung Block 2, Hillview Court 5517 Tsuen Wan Hoi Pa San Tsuen 5518 Central & Western Flourish Court 5520 1 Related Confirmed / District Building Name Probable Case(s) Wong Tai Sin Fu Tung House, Tung Tau Estate 5521 Yau Tsim Mong Tai Chuen Building, Cosmopolitan Estates 5523 Yau Tsim Mong Yan Hong Building 5524 Sha Tin Block 5, Royal Ascot 5525 Sha Tin Yiu Ping House, Yiu On Estate 5526 Sha Tin Block 5, Royal Ascot 5529 Wan Chai Block E, Beverly Hill 5530 Yau Tsim Mong Tower 1, The Harbourside 5531 Yuen Long Wah Choi House, Tin Wah Estate 5532 Yau Tsim Mong Lee Man Building 5533 Yau Tsim Mong Paradise Square 5534 Kowloon City Tower 3, K. -

5 Days in HK

5 days in HK Contact us | turipo.com | [email protected] 5 days in HK Our Hong Kong trip plan. Full day by day travel plan for our summer vacaon in Hong Kong. It is hard to visualize unless you’ve been there and experienced the energy that envelops the enre country. Every corner of Hong Kong has something to discover, here are the top aracons and things to do in Hong Kong to consider, our China travel guide. Contact us | turipo.com | [email protected] Day 1 - Hong Kong Park & Victoria Peak Contact us | turipo.com | [email protected] Day 1 - Hong Kong Park & Victoria Peak 1. Hong Kong Park 4. Victoria Peak Duration ~ 2 Hours Duration ~ 1 Hour Mid-level, Hong Kong Victoria Peak, The Peak, Hong Kong Rating: 4.5 Start the day off with an invigorang walk through Hong Kong Park, admiring fountains, landscaping, and even an At the summit, incredible visuals await—especially around aviary before heading towards the Peak Tram, which takes sunset. you to the top of the famous Victoria Peak. WIKIPEDIA Victoria Peak is a mountain in the western half of Hong Kong 2. Hong Kong Zoological And Botanical Gardens Island. It is also known as Mount Ausn, and locally as The Duration ~ 1 Hour Peak. With an elevaon of 552 m, it is the highest mountain on Hong Kong island, ranked 31 in terms of elevaon in the Hong Kong Hong Kong Special Administrave Region. The summit is Rating: 2.9 more.. Nearby the peak Tram Hong Kong Zoological and Botanical Gardens, a free aracon, is also not even 5 minutes away from the Peak Tram. -

Old Town Central - Enrich Visitor’S Experience

C&WDC WG on DC Affairs Paper No. 2/2017 OldOld TTownown CCentralentral 1 Old Town Central - Enrich Visitor’s Experience A contemporary lifestyle destination and a chronicle of how Arts, Heritage, Creativity, and Dining & Entertainment evolved in the city Bounded by Wyndham Street, Caine Road, Possession Street and Queen’s Road Central Possession Street Queen’s Road Central Caine Road Wyndham Street Key Campaign Elements DIY Walking Guide Heritage & Art History Integrated Marketing Local & Overseas Publicity Launch Ceremony City Ambience Tour Products 3 5 Thematic ‘Do-It-Yourself’ Routes For visitors to explore the abundant treasure according to their own interests and pace. Heritage & Dining & Art Treasure Hunt All-in-one History Entertainment Possession Street, Tai Ping Shan PoHo, Upper PMQ, Hollywood Graham market & Best picks Street, Lascar Row, Road, Peel Street, around, LKF, from each Man Mo Temple, StauntonS Street & Aberdeen Street SoHo, Ladder Street, around route Tai Kwun 4 Sample route: All-in-one Walking Tour Route for busy visitors 1. Possession Street (History) 1 6: Gough Street & Kau U Fong (Creative & Design – Designer stores, boutiques 2 4: Man Mo Temple Dining – Local food stalls & (Heritage - Declared International cuisine) 2: POHO - Tai Ping Shan Street (Local Monument ) culture – Temples / Stores/ Restaurant) 6 (Art & Entertainment – Galleries / 4 Street Art/ Café ) 3 7 5 7: Pak Tsz Lane Park 5: PMQ (History) 3: YMCA Bridges Street Centre & ( Heritage - 10: Pottinger Ladder Street Arts & Dining – Galleries, Street -

Hong Kong Stopover

HONG KONG STOPOVER Why not break up your trip to Europe or America with an exciting Hong Kong stopover? Experience a taste of Asia’s World City in just 48 or 72 hours... Fast Facts Must do’s in Hong Kong Geography - situated on the south-eastern coast Attractions of China. Hong Kong is comprised of Hong Kong • The Big Buddha Island, Kowloon, New Territories and over 260 • Star Ferry outlying islands. • HK Disneyland • Street Markets Currency - Hong Kong dollars (HK$) • The Peak Electricity - 220V/50Hz UK plug Day Tours • Big Bus Tours Visas - Australian and New Zealand passport • Hong Kong Island Tour holders DO NOT require a visa for stays up to 90 • Victoria Harbour Cruise days in Hong Kong • Hong Kong Foodie Tours Language - Cantonese, Mandarin, English Dining • Dim sum • Chinese BBQ Transport • Fusion • Fine dining Airport Express Link • Local snacks One of the world’s leading Airport railway systems, offers you a swift and inexpensive trip Shopping between Hong Kong International Airport (HKIA) Shopping areas and either Kowloon (22 mins) or Hong Kong • Hong Kong Island - Station (24 mins) Central, Causeway Bay • Kowloon - Tsim Sha Tsui, Single ticket cost - HK$100 (Kowloon) or HK$110 Nathan Road (HK Island) Malls & Department stores Return ticket cost - HK$185 (Kowloon) or HK$205 • Hong Kong Island - IFC Mall, Times (HK Island) Square • Kowloon - Harbour City Octopus Card • Lantau Island - Citygate Outlets This is an electronic fare card accepted on most public transport, most fast food chains and stores. Street Markets Can be purchased at any MTR station, Airport • Hong Kong Island - Stanley Express and Ferry Customer Service. -

Hong Kong, 1941-1945

Hong Kong University Press 14/F Hing Wai Centre 7 Tin Wan Praya Road Aberdeen Hong Kong © Ray Barman 2009 ISBN 978-962-209-976-0 All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. All photos, illustrations, and newspaper cuttings in this book are from the collection of the Barman family. Every effort has been made to track ownership and formal permission from the copyright holders. If there are any inadvertent omissions we apologize to those concerned, and ask that they contact us so that we can correct any oversight as soon as possible. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Secure On-line Ordering http://www.hkupress.org Printed and bound by Condor Production Ltd., Hong Kong, China. Contents Foreword for the Series ix About This Book xi Abbreviations xiii About the Author xvii Introduction 1 The Battle 5 Internment 93 Postscript 265 Appendices 269 Notes 293 Index 299 About the Author Charles Edward Barman was born at Canterbury, Kent in England on 14 May 1901, the eldest of four children. He was the son of a gardener, Richard Thomas, and Emily Barman from Tenterden, an area of Kent where many people of the Barman name still live. Charles had two brothers, Richard and George, and a younger sister, Elsie. As a boy, he attended the local primary school at Canterbury and attended services at the Cathedral. -

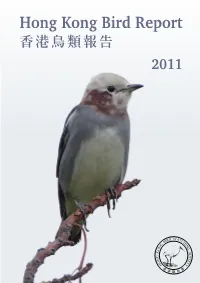

Hong Kong Bird Report 2011

Hong Kong Bird Report 2011 Hong Kong Bird Report 香港鳥類報告 2011 香港鳥類報告 Birdview report 2009-2010_MINOX.indd 1 5/7/12 1:46 PM Birdview report 2009-2010_MINOX.indd 1 5/7/12 1:46 PM 防雨水設計 8x42 EXWP I / 10x42 EXWP I • 8倍放大率 / 10倍放大率 • 防水設計, 尤合戶外及水上活動使用 • 密封式內充氮氣, 有效令鏡片防霞防霧 • 高折射指數稜鏡及多層鍍膜鏡片, 確保影像清晰明亮 • 能阻隔紫外線, 保護視力 港澳區代理:大通拓展有限公司 荃灣沙咀道381-389號榮亞工業大廈一樓C座 電話:(852) 2730 5663 傳真:(852) 2735 7593 電郵:[email protected] 野 外 觀 鳥 活 動 必 備 手 冊 www.wanlibk.com 萬里機構wanlibk.com www.hkbws.org.hk 觀鳥.indd 1 13年3月12日 下午2:10 Published in Mar 2013 2013年3月出版 The Hong Kong Bird Watching Society 香港觀鳥會 7C, V Ga Building, 532 Castle Peak Road , Lai Chi Kok, Kowloon , Hong Kong, China 中國香港九龍荔枝角青山道532號偉基大廈7樓C室 (Approved Charitable Institution of Public Character) (認可公共性質慈善機構) Editors: John Allcock, Geoff Carey, Gary Chow and Geoff Welch 編輯:柯祖毅, 賈知行, 周家禮, Geoff Welch 版權所有,不准翻印 All rights reserved. Copyright © HKBWS Printed on 100% recycled paper with soy ink. 全書採用100%再造紙及大豆油墨印刷 Front Cover 封面: Chestnut-cheeked Starling Agropsar philippensis 栗頰椋鳥 Po Toi Island, 5th October 2011 蒲台島 2011年10月5日 Allen Chan 陳志雄 Hong Kong Bird Report 2011: Committees The Hong Kong Bird Watching Society 香港觀鳥會 Committees and Officers 2013 榮譽會長 Honorary President 林超英先生 Mr. Lam Chiu Ying 執行委員會 Executive Committee 主席 Chairman 劉偉民先生 Mr. Lau Wai Man, Apache 副主席 Vice-chairman 吳祖南博士 Dr. Ng Cho Nam 副主席 Vice-chairman 吳 敏先生 Mr. Michael Kilburn 義務秘書 Hon. Secretary 陳慶麟先生 Mr. Chan Hing Lun, Alan 義務司庫 Hon. Treasurer 周智良小姐 Ms. Chow Chee Leung, Ada 委員 Committee members 李慧珠小姐 Ms. Lee Wai Chu, Ronley 柯祖毅先生 Mr. -

Egn201014152134.Ps, Page 29 @ Preflight ( MA-15-6363.Indd )

G.N. 2134 ELECTORAL AFFAIRS COMMISSION (ELECTORAL PROCEDURE) (LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL) REGULATION (Section 28 of the Regulation) LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL BY-ELECTION NOTICE OF DESIGNATION OF POLLING STATIONS AND COUNTING STATIONS Date of By-election: 16 May 2010 Notice is hereby given that the following places are designated to be used as polling stations and counting stations for the Legislative Council By-election to be held on 16 May 2010 for conducting a poll and counting the votes cast in respect of the geographical constituencies named below: Code and Name of Polling Station Geographical Place designated as Polling Station and Counting Station Code Constituency LC1 A0101 Joint Professional Centre Hong Kong Island Unit 1, G/F., The Center, 99 Queen's Road Central, Hong Kong A0102 Hong Kong Park Sports Centre 29 Cotton Tree Drive, Central, Hong Kong A0201 Raimondi College 2 Robinson Road, Mid Levels, Hong Kong A0301 Ying Wa Girls' School 76 Robinson Road, Mid Levels, Hong Kong A0401 St. Joseph's College 7 Kennedy Road, Central, Hong Kong A0402 German Swiss International School 11 Guildford Road, The Peak, Hong Kong A0601 HKYWCA Western District Integrated Social Service Centre Flat A, 1/F, Block 1, Centenary Mansion, 9-15 Victoria Road, Western District, Hong Kong A0701 Smithfield Sports Centre 4/F, Smithfield Municipal Services Building, 12K Smithfield, Kennedy Town, Hong Kong Code and Name of Polling Station Geographical Place designated as Polling Station and Counting Station Code Constituency A0801 Kennedy Town Community Complex (Multi-purpose -

Issue No. 22 June 2012 Feature Article Contents Study on The

Issue No. 22 June 2012 www.hkbiodiversity.net Feature Article Contents Study on the Distribution and Habitat Feature Article: Study on the Distribution and Habitat Characteristics of the Chinese Grassbird Characteristics of Chinese Grassbird (Graminicola striatus, 大草鶯) in Hong (Graminicola striatus, 大草鶯) Kong in Hong Kong page 1 Ivy W.Y. So1, Judy H.C. Wan1, W.H. Lee1, William W.W. Cheng2 Working Group Column: 1Bird Working Group Experimentation on the Use of 2Nature Conservation Division Bat Boxes in Hong Kong page 10 漁農自然護理署鳥類工作小組於2011年夏季進行一項有關大草 鶯(Graminicola striatus) 的生態研究,發現大草鶯於本港的分布與舊 An Estimation of the Current Population 有記錄相似,估計現時本港的大草鶯數目約有490隻,其生境於三 Size of Yellow-crested Cockatoo 月至九月主要為海拔200米以上、長度及密度高的草地,而芒屬則 (Cacatua sulphurea, 小葵花鳳頭鸚鵡) 是其生境中覆蓋率最高的植物。 in Hong Kong page 15 Background Rare Lizard Found: Bogadek’s The Chinese Grassbird (Graminicola striatus, 大草鶯) (Fig. 1) is a newly recognised species that has been split from the Indian Grassbird Burrowing Lizard (Dibamous bogadeki, (G. bengalensis; formerly known as the Rufous-rumped Grassbird). 香港雙足蜥) page 17 The split of the grassbirds, which was proposed in 2010 based on a morphological, vocal and genetic study (Leader et al., 2010), was recently accepted by the International Ornithologists’ Union in January 2012 (Gill & Donsker, 2012). Subscribing Hong Kong Biodiversity If you would like to have a copy, or Fig. 1. The Chinese Grassbird. if you know anyone who is interested in receiving a copy of this newsletter, please send the name, organisation, and email (soft copy) or postal addresses (hard copy) to the Article Editor. Chief Editor : Simon K.F. CHAN ([email protected]) Article Editor : Aidia S.W. -

Hong Kong Guide

HONG KONG GUIDE YOUR FREE HONG KONG GUIDE FROM THE ASIA TRAVEL SPECIALISTS www.asiawebdirect.com Hong Kong is cosmopolitan, exciting and impressive and stands out as a definite ‘must-see’ city. The contrasts of the New Territories to downtown Kowloon could not be starker and even though Hong Kong is a full-on working town its entertainment options are a wonder. Asia's largest shopping hub will present you with a challenge: just how to take all the best retail outlets in on time and the same goes for the fabulous choice of dining. City-wide you'll be amazed at the nightlife options and how the city transforms once the sun sets. Accommodation choices are plentiful. Take enough time to get to know this fascinating destination at your leisure and take in the sights and sounds of one of Asia’s most vibrant cities. WEATHER http://www.hong-kong-hotels.ws/general-info.htm Hong Kong can be considered a year-round destination with a mild climate from the middle of September to February, and warm and humid weather from May to mid-September. SIM CARDS AND DIALING PREFIXES It’s cool and dry in the winter (December to March), and hot, humid and rainy from spring and summer; July records the highest average Prepaid SIM cards are available at cell phone shops and most temperature. Autumn is warm, sunny, and dry. Hong Kong occasionally convenience stores (7-Elevens and Circle K are everywhere). The big experiences severe rainstorms, or typhoons. It rains a lot between May mobile phone service providers here include CSL, PCCW, Three (3) and SmarTone. -

Ngong Ping 360 Cause of Suspension of Service on 11 April 2008

Ngong Ping 360 Cause of Suspension of Service on 11 April 2008 The Incident The Ngong Ping 360 ropeway service was suspended for 1 hour 28 minutes on 11 April 2008. The operating company has completed their investigation and submitted their investigation report to EMSD. The cause of the incident together with the remedial actions are given in the following paragraphs. Nei Lak Shan Angle Station The route of the Ngong Ping 360 ropeway has two angle stations, namely Airport Island Angle Station, and Nei Lak Shan Angle Station. The route of the Ngong Ping 360 ropeway and the locations of the angle stations are given in Figure A. Nei Lak Shan Figure A Plan view of Ngong Ping ropeway Findings The fault diagnosis conducted by the operating company revealed that a set of driving belts at one of the belt/pulley assemblies at Nei Lak Shan Angle Station dislodged from their normal position, resulting in incorrect cabin separation within the angle station. During normal operation, Nei Lak Shan Angle Station only has a small team of operators carrying out operation of the system. The repair work of the belt/pulley assemblies required experienced members of the maintenance team to be deployed from the Tung Chung Terminal. As Nei Lak Shan is quite remote from Tung Chung and there is only foot path leading to the angle station, the repair work at the angle station therefore took longer time than usual. Immediate Actions Taken The maintenance team of the operating company conducted corrective actions, included replacing the affected pulley, tightening the belts of the affected belt/pulley assembly to provide proper tension and fine-adjusting the assembly to to reduce the tendency of belt dislodgement.