Issue No. 22 June 2012 Feature Article Contents Study on The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Events in 2013

Events in 2013 The 16.5 metre-high yellow Rubber Duck, a floating sculpture created by Dutch artist Florentijn Hofman, arrives at Ocean Terminal/Harbour City in Kowloon in May on its world tour. 1 1. The Chief Executive, Mr C Y Leung (second from left), rings the closing bell at the New York Stock Exchange in June. 2. The Ceremonial Opening of the Legal Year in January. 3. The Chief Executive meets the President of Mexico, Mr Enrique Peña Nieto, at Government House in April. 4. The Secretary for Justice, Mr Rimsky Yuen, SC (left), the Chief Secretary for Administration, Mrs Carrie Lam, and the Secretary for Constitutional and Mainland Affairs, Mr Raymond Tam, launch the public consultation on electoral reform in December. 5. The Financial Secretary, Mr John C Tsang (right), meets the French Minister of the 3 Economy and Finance, Mr Pierre Moscovici, in Paris in November. 2 5 4 1 2 1. Sarah Lee Wai-sze wins gold in the Women’s 500 metre time trial race at the UCI Track Cycling World Championships in Minsk, Belarus, in February. (Photo courtesy of Hong Kong Cycling Association) 2. The Mariner of the Seas is welcomed at the inaugural berthing at the Kai Tak Cruise Terminal in June. 3. ‘Big Waster’ headlined the year’s ‘Food Wise Hong Kong’ campaign to reduce food waste. 4. The Hong Kong Maritime Museum opened in February. 3 4 4 1 1. Visitors enjoy the ‘Journey to Hong Kong’ exhibition in Moscow in October. 2. Hong Kong cartoon characters McDull and McMug at the City of London Lord Mayor’s Show in November. -

Disaggregation of Bird Families Listed on Cms Appendix Ii

Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals 2nd Meeting of the Sessional Committee of the CMS Scientific Council (ScC-SC2) Bonn, Germany, 10 – 14 July 2017 UNEP/CMS/ScC-SC2/Inf.3 DISAGGREGATION OF BIRD FAMILIES LISTED ON CMS APPENDIX II (Prepared by the Appointed Councillors for Birds) Summary: The first meeting of the Sessional Committee of the Scientific Council identified the adoption of a new standard reference for avian taxonomy as an opportunity to disaggregate the higher-level taxa listed on Appendix II and to identify those that are considered to be migratory species and that have an unfavourable conservation status. The current paper presents an initial analysis of the higher-level disaggregation using the Handbook of the Birds of the World/BirdLife International Illustrated Checklist of the Birds of the World Volumes 1 and 2 taxonomy, and identifies the challenges in completing the analysis to identify all of the migratory species and the corresponding Range States. The document has been prepared by the COP Appointed Scientific Councilors for Birds. This is a supplementary paper to COP document UNEP/CMS/COP12/Doc.25.3 on Taxonomy and Nomenclature UNEP/CMS/ScC-Sc2/Inf.3 DISAGGREGATION OF BIRD FAMILIES LISTED ON CMS APPENDIX II 1. Through Resolution 11.19, the Conference of Parties adopted as the standard reference for bird taxonomy and nomenclature for Non-Passerine species the Handbook of the Birds of the World/BirdLife International Illustrated Checklist of the Birds of the World, Volume 1: Non-Passerines, by Josep del Hoyo and Nigel J. Collar (2014); 2. -

Hong Kong Bird Report 2011

Hong Kong Bird Report 2011 Hong Kong Bird Report 香港鳥類報告 2011 香港鳥類報告 Birdview report 2009-2010_MINOX.indd 1 5/7/12 1:46 PM Birdview report 2009-2010_MINOX.indd 1 5/7/12 1:46 PM 防雨水設計 8x42 EXWP I / 10x42 EXWP I • 8倍放大率 / 10倍放大率 • 防水設計, 尤合戶外及水上活動使用 • 密封式內充氮氣, 有效令鏡片防霞防霧 • 高折射指數稜鏡及多層鍍膜鏡片, 確保影像清晰明亮 • 能阻隔紫外線, 保護視力 港澳區代理:大通拓展有限公司 荃灣沙咀道381-389號榮亞工業大廈一樓C座 電話:(852) 2730 5663 傳真:(852) 2735 7593 電郵:[email protected] 野 外 觀 鳥 活 動 必 備 手 冊 www.wanlibk.com 萬里機構wanlibk.com www.hkbws.org.hk 觀鳥.indd 1 13年3月12日 下午2:10 Published in Mar 2013 2013年3月出版 The Hong Kong Bird Watching Society 香港觀鳥會 7C, V Ga Building, 532 Castle Peak Road , Lai Chi Kok, Kowloon , Hong Kong, China 中國香港九龍荔枝角青山道532號偉基大廈7樓C室 (Approved Charitable Institution of Public Character) (認可公共性質慈善機構) Editors: John Allcock, Geoff Carey, Gary Chow and Geoff Welch 編輯:柯祖毅, 賈知行, 周家禮, Geoff Welch 版權所有,不准翻印 All rights reserved. Copyright © HKBWS Printed on 100% recycled paper with soy ink. 全書採用100%再造紙及大豆油墨印刷 Front Cover 封面: Chestnut-cheeked Starling Agropsar philippensis 栗頰椋鳥 Po Toi Island, 5th October 2011 蒲台島 2011年10月5日 Allen Chan 陳志雄 Hong Kong Bird Report 2011: Committees The Hong Kong Bird Watching Society 香港觀鳥會 Committees and Officers 2013 榮譽會長 Honorary President 林超英先生 Mr. Lam Chiu Ying 執行委員會 Executive Committee 主席 Chairman 劉偉民先生 Mr. Lau Wai Man, Apache 副主席 Vice-chairman 吳祖南博士 Dr. Ng Cho Nam 副主席 Vice-chairman 吳 敏先生 Mr. Michael Kilburn 義務秘書 Hon. Secretary 陳慶麟先生 Mr. Chan Hing Lun, Alan 義務司庫 Hon. Treasurer 周智良小姐 Ms. Chow Chee Leung, Ada 委員 Committee members 李慧珠小姐 Ms. Lee Wai Chu, Ronley 柯祖毅先生 Mr. -

MARINE DEPARTMENT NOTICE NO. 48 of 2018 (Navigational & Seamanship Safety Practices) Marine Sporting Activities for the Year 2018/19

MARINE DEPARTMENT NOTICE NO. 48 OF 2018 (Navigational & Seamanship Safety Practices) Marine Sporting Activities For The Year 2018/19 NOTICE IS HEREBY GIVEN that the following marine sporting activities under the auspices of various clubs and associations will take place throughout the year in areas listed below. This list is not exhaustive. Races will normally be conducted during weekends and Public Holidays unless otherwise specified. Yacht Races : Beaufort Island, Bluff Head, Cape D’Aguilar, Cheung Chau, Chung Hom Kok, Deep Water Bay, Discovery Bay, Hei Ling Chau, Junk Bay, Lamma Island, the north and south of Lantau Island, Ma Wan Channel, Mirs Bay, and areas off Ninepin Group, Peng Chau, Plover Cove, Po Toi Island, Port Shelter, Repulse Bay, Rocky Harbour, Round Island, Shek Kwu Chau, Siu Kau Yi Chau, Soko Islands, South Bay, Stanley Bay, Steep Island, Sung Kong, Sunshine Island, Tai Long Pai, Tai Tam Bay, Tathong Channel, Tolo Harbour, Eastern Victoria Harbour and Waglan Island. Windsurfing Races : Inner Port Shelter, Long Harbour, Lung Kwu Tan, Plover Cove, Shek O Wan, Sheung Sze Mun, Shui Hau Wan, Stanley Bay, Tai Tam Bay, Tolo Harbour and Tung Wan of Cheung Chau. Canoe Races : Beaufort Island, Bluff Head, Cape D’Aguilar, Castle Peak Bay, Cheung Chau, Clear Water Bay, Deep Water Bay, Discovery Bay, east of Lantau Island, Long Harbour, Man Kok Tsui, Ninepin Group, Peng Chau, Plover Cove, Port Shelter, Repulse Bay, Rocky Harbour, Shing Mun River Channel, Shek O Wan, South Bay, Siu Kau Yi Chau, Stanley Bay, Steep Island, Tai Lam Chung, Tai Tam Bay, Tai O, Tolo Harbour and Tung Chung. -

Challenging 12 Hours 2019 Course Description

Challenging 12 hours 2019 Course Description Yau Tong - CP1 Tseng Lan Shue (7km) Start with 2km on gentle uphill pedestrian pavement,then step on Wilson trail towards Black Hill. Upon reaching the top, go down and up several gentle slopes before arriving at Ma Yau Tong Village. Walk along the village road for 2km to Sun Tei Village and continue 1km on concrete village path, you reach CP1 Tsang Lan Shue,This CP only provides drinking water. CP1 Tsang Lan Shue – SS1 Tai Lam Wu – SS2 Tung Yeung Shan – CP2 Shatin Pass Pavilion (8km) Depart from CP1 on the concrete village path of Tsang Lan Shue. Continue on the trail steps of Wilson Trail and up a small hill called Wong Keng Tsai. Beware of the slippery stone steps covered with moss and protruded roots on this 1.7km section. SS1 Tai Lam Wu provides snacks and drinks. SS1 Tai Lam Wu – SS2 Tung Yeung Shan Depart from SS1 on a short stretch of water catchment road,then start the strenuous Tung Yeung Shan uphill section. This 1.5km sections has an accumulated ascent of 400m and there is little shade on the upper part. However, the view is broad on high grounds and you can see the whole Sai Kung peninsula. SS2 Tung Yeung Shan provides only drinking water. SS2 Tung Yeung Shan – CP2 Shatin Pass pavilion Continue with 3.3km downhill concrete road towards CP2 Shatin Pass pavilion on Fei Ngo Shan Road and Shatin Pass Road. The whole of Kowloon peninsula and north Hong Kong Island is on your left. -

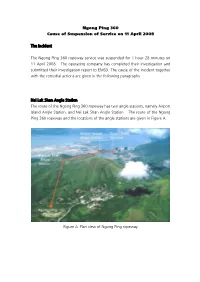

Ngong Ping 360 Cause of Suspension of Service on 11 April 2008

Ngong Ping 360 Cause of Suspension of Service on 11 April 2008 The Incident The Ngong Ping 360 ropeway service was suspended for 1 hour 28 minutes on 11 April 2008. The operating company has completed their investigation and submitted their investigation report to EMSD. The cause of the incident together with the remedial actions are given in the following paragraphs. Nei Lak Shan Angle Station The route of the Ngong Ping 360 ropeway has two angle stations, namely Airport Island Angle Station, and Nei Lak Shan Angle Station. The route of the Ngong Ping 360 ropeway and the locations of the angle stations are given in Figure A. Nei Lak Shan Figure A Plan view of Ngong Ping ropeway Findings The fault diagnosis conducted by the operating company revealed that a set of driving belts at one of the belt/pulley assemblies at Nei Lak Shan Angle Station dislodged from their normal position, resulting in incorrect cabin separation within the angle station. During normal operation, Nei Lak Shan Angle Station only has a small team of operators carrying out operation of the system. The repair work of the belt/pulley assemblies required experienced members of the maintenance team to be deployed from the Tung Chung Terminal. As Nei Lak Shan is quite remote from Tung Chung and there is only foot path leading to the angle station, the repair work at the angle station therefore took longer time than usual. Immediate Actions Taken The maintenance team of the operating company conducted corrective actions, included replacing the affected pulley, tightening the belts of the affected belt/pulley assembly to provide proper tension and fine-adjusting the assembly to to reduce the tendency of belt dislodgement. -

Mai Po Nature Reserve Management Plan: 2019-2024

Mai Po Nature Reserve Management Plan: 2019-2024 ©Anthony Sun June 2021 (Mid-term version) Prepared by WWF-Hong Kong Mai Po Nature Reserve Management Plan: 2019-2024 Page | 1 Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................................................... 2 1. INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................................................... 7 1.1 Regional and Global Context ........................................................................................................................ 8 1.2 Local Biodiversity and Wise Use ................................................................................................................... 9 1.3 Geology and Geological History ................................................................................................................. 10 1.4 Hydrology ................................................................................................................................................... 10 1.5 Climate ....................................................................................................................................................... 10 1.6 Climate Change Impacts ............................................................................................................................. 11 1.7 Biodiversity ................................................................................................................................................ -

Index of Handbook of the Mammals of the World. Vol. 9. Bats

Index of Handbook of the Mammals of the World. Vol. 9. Bats A agnella, Kerivoula 901 Anchieta’s Bat 814 aquilus, Glischropus 763 Aba Leaf-nosed Bat 247 aladdin, Pipistrellus pipistrellus 771 Anchieta’s Broad-faced Fruit Bat 94 aquilus, Platyrrhinus 567 Aba Roundleaf Bat 247 alascensis, Myotis lucifugus 927 Anchieta’s Pipistrelle 814 Arabian Barbastelle 861 abae, Hipposideros 247 alaschanicus, Hypsugo 810 anchietae, Plerotes 94 Arabian Horseshoe Bat 296 abae, Rhinolophus fumigatus 290 Alashanian Pipistrelle 810 ancricola, Myotis 957 Arabian Mouse-tailed Bat 164, 170, 176 abbotti, Myotis hasseltii 970 alba, Ectophylla 466, 480, 569 Andaman Horseshoe Bat 314 Arabian Pipistrelle 810 abditum, Megaderma spasma 191 albatus, Myopterus daubentonii 663 Andaman Intermediate Horseshoe Arabian Trident Bat 229 Abo Bat 725, 832 Alberico’s Broad-nosed Bat 565 Bat 321 Arabian Trident Leaf-nosed Bat 229 Abo Butterfly Bat 725, 832 albericoi, Platyrrhinus 565 andamanensis, Rhinolophus 321 arabica, Asellia 229 abramus, Pipistrellus 777 albescens, Myotis 940 Andean Fruit Bat 547 arabicus, Hypsugo 810 abrasus, Cynomops 604, 640 albicollis, Megaerops 64 Andersen’s Bare-backed Fruit Bat 109 arabicus, Rousettus aegyptiacus 87 Abruzzi’s Wrinkle-lipped Bat 645 albipinnis, Taphozous longimanus 353 Andersen’s Flying Fox 158 arabium, Rhinopoma cystops 176 Abyssinian Horseshoe Bat 290 albiventer, Nyctimene 36, 118 Andersen’s Fruit-eating Bat 578 Arafura Large-footed Bat 969 Acerodon albiventris, Noctilio 405, 411 Andersen’s Leaf-nosed Bat 254 Arata Yellow-shouldered Bat 543 Sulawesi 134 albofuscus, Scotoecus 762 Andersen’s Little Fruit-eating Bat 578 Arata-Thomas Yellow-shouldered Talaud 134 alboguttata, Glauconycteris 833 Andersen’s Naked-backed Fruit Bat 109 Bat 543 Acerodon 134 albus, Diclidurus 339, 367 Andersen’s Roundleaf Bat 254 aratathomasi, Sturnira 543 Acerodon mackloti (see A. -

Jockey Club Age-Friendly City Project

Table of Content List of Tables .............................................................................................................................. i List of Figures .......................................................................................................................... iii Executive Summary ................................................................................................................. 1 1. Introduction ...................................................................................................................... 3 1.1 Overview and Trend of Hong Kong’s Ageing Population ................................ 3 1.2 Hong Kong’s Responses to Population Ageing .................................................. 4 1.3 History and Concepts of Active Ageing in Age-friendly City: Health, Participation and Security .............................................................................................. 5 1.4 Jockey Club Age-friendly City Project .............................................................. 6 2 Age-friendly City in Islands District .............................................................................. 7 2.1 Background and Characteristics of Islands District ......................................... 7 2.1.1 History and Development ........................................................................ 7 2.1.2 Characteristics of Islands District .......................................................... 8 2.2 Research Methods for Baseline Assessment ................................................... -

Annotated List of Amphibian and Reptile Taxa Described by Ilya Sergeevich Darevsky (1924–2009)

Zootaxa 4803 (1): 152–168 ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) https://www.mapress.com/j/zt/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2020 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4803.1.8 http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:F722FC45-D748-4128-942C-76BD53AE9BAF Annotated list of amphibian and reptile taxa described by Ilya Sergeevich Darevsky (1924–2009) ANDREI V. BARABANOV1,2 & IGOR V. DORONIN1,3,* 1Department of Herpetology, Zoological Institute (ZISP), Russian Academy of Sciences, St. Petersburg 199034 Universitetskaya nab. 1, Russia 2 �[email protected] 3 �[email protected], [email protected]; https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1000-3144 *Corresponding author Abstract Ilya S. Darevsky co-described 70 taxa (three genera, 46 species, 21 subspecies) in 44 publications belonging to five orders, eight families of amphibians and reptiles during his career in herpetology. Of this number, three taxa are fossil and 57 taxa are currently considered as valid. By the regions where new taxa were discovered Southeast Asia and Western Asia (includes Caucasus and Asia Minor) dominates. The largest number of descriptions was published in the Russian Journal of Herpetology. Key words: herpetological collections, list of taxa, Ilya Sergeevich Darevsky, type specimens Introduction In 2019, the scientific community celebrated the 95th anniversary of the outstanding zoologist, evolutionist and bio- geographer, corresponding member of the USSR Academy of Sciences (Russian Academy of Sciences), Professor Ilya Sergeevich Darevsky (1924–2009) (Fig. 1). One of the most well-known herpetologists in the world, Darevsky was famous not only for his research on the biodiversity of amphibians and reptiles, but also for the discovery of natural parthenogenesis, hybridization, and polyploidy in higher vertebrates, which fundamentally changed biolo- gists’ views on speciation mechanisms in animals and brought him worldwide recognition. -

Sunset Peak Is Famous for Its Stunning Sunset Views and Seas of Silvergrass, Especially in Autumn

A SENSE OF PLACE Being outdoors has important effects on our smells of the forest, or of drying fish and mental and physical wellbeing, especially shrimp paste in a traditionalvillage; visit when we are active, such as when we are shorelines where you can touch rocks that bear hiking. Though Hong Kong is thought of as a the scars of a volcanic past. concrete jungle, its density means that the wild outdoors is closer to downtown streets than it Engaging your senses like this is a powerful is in other parts of the world so those healthy way to create shared memories withfriends escapes are easily attained. and family. It also shows how Hong Kong’s countryside is not a secondaryattraction but Once there, you can open your senses wide. rather is key to the city’s appeal. Gaze back at the city skyline seenfrom the mountains; listen to waves crashing on remote Now, let’s indulge our sense of touch as beaches; savour the taste oflocal dishes we enjoy some of Hong Kong’s outdoor that connect you with Hong Kong’s cultural playgrounds. heritage; take a deep breathand absorb the Discover Hong Kong © Copyright Hong Kong Tourism Board 2020 1 2 GREAT OUTDOORS HONG KONG HIKING & CYCLING GUIDEBOOK TIPS & GEAR Check out these hiking tips and our recommended gear checklist to help you have a safe and enjoyable hike. Open your senses FOOD & DRINK and go explore! Never eat or drink while moving. Never drink untreated water from hill streams or eat any wild plants or mushrooms. Don’t consume icy drinks immediately after a long hike, when your PACKING body temperature is still high. -

NE INDIA 2018 by Starling Reizen

North-east India: a report on the birds seen during a trip to Assam and Arunachal Pradesh from 31 March till 15 April 2018 Blue-naped Pitta at Koklabari Agriculture Farm, photographed by Pablo Vercruysse © 2018 Leader: David Van den Schoor Participants: Rudy Lenaerts, Pablo Vercruysse, Herwig Blockx and Paul De Cnodder INTRODUCTION After an exploration trip last year, this was Starling's first tour to Eaglenest Wildlife Sanctuary, which, though discovered only recently, has proved very popular among the more adventurous of the birding community. Combined with nearby areas in western Arunachal Pradesh and Assam, in India’s remote northeast corner, it offers a fantastic range of special birds. Despite some windy and wet weather on occasions, we had fair weather for most of our trip, enabling us to enjoy the birding. Altogether, we recorded a total of 450 species, during our 14 days but as always, it is quality, not quantity that impressed us most. Birding highlights of this wonderful tour included a male Blyth’s Tragopan, which we saw quite well, Himalayan Monals, tame and noisy Snow Partridges, displaying Bengal Floricans, walk away views on a fantastic male Blue-naped Pitta, several amazing Ward’s Trogons, excellent views on both males and females Rufous-necked Hornbills, close-up views on many grassland specialities like Indian and Bristled Grassbirds, Black-breasted Parrotbills, Jerdon’s Babbler and Finn’s Weavers. Five of the rare White-winged Duck at Nameri, great views of Spotted Elachuras, Long-billed and Bar-winged Wren- babblers, male and female Fire-tailed Mysornis and a large gathering of Greater Adjutants at their home dump.