€R«Est NEWMAN Py;:Gi/^Jg»K'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Early 20Th Century Classical

Early 20th Century Classical Contents A few highlights 1 Background stories 1 Early 20th Century Classical – Title order 2 Early 20th Century Classical – Composer order 9 Early 20th Century Classical – Pianist order 17 The 200 MIDI files in this category include works by 20th Century composers such as Debussy, Fauré, Granados, Milhaud, Korngold, Rachmaninoff, Ravel and Respighi. Some of the works are from the late 19th century, giving a snapshot of music from the Romantics, through Impressionists to modern day compositions. Pianists include Alexander Brailowsky, Ottorino Respighi, Claude Debussy; Ernő Dohnányi, Walter Gieseking, Percy Grainger, Enrique Granados, Leo Ornstein, Sergei Prokofiev, Sergei Rachmaninoff and Maurice Ravel. The composers in this list are usually playing their own works. A few highlights Afternoon of a Faun (Prelude to) by Debussy played by Richard Singer (two rolls joined) Allegro De Concierto (Concert Allegro) by Granados, played by Granados’ pupil Paquita Madriguera Enigma Variations (complete) by Elgar, played by duo pianists Cuthbert Whitmore & Dorothy Manley Flirtation in a Chinese Garden; Rush Hour in Hong Kong by Abram Chasins, played by the composer Fountains of Rome by Respighi, played by the composer and Alfredo Casella Malagueña, by Ernesto Lecuona, played by the composer Naila Ballet Waltz, by Delibes, arranged by Dohnányi, played by Mieczyslaw Munz Pictures at an Exhibition (incomplete) by Moussgorsky played by Sergei Prokofiev Rhapsodies Op.11 (1 to 4), by Dohnányi, all but one (No.3) played by the composer Spanish Dances (Danza Espanolas) by Granados, played by the composer Turkey Op.18, No.3 (In The Garden Of The Old Harem) by Blanchet, played by Ervin Nyiregyházi Waltzes Noble and Sentimental, by Ravel played by the composer. -

≥ Elgar Sea Pictures Polonia Pomp and Circumstance Marches 1–5 Sir Mark Elder Alice Coote Sir Edward Elgar (1857–1934) Sea Pictures, Op.37 1

≥ ELGAR SEA PICTURES POLONIA POMP AND CIRCUMSTANCE MARCHES 1–5 SIR MARK ELDER ALICE COOTE SIR EDWARD ELGAR (1857–1934) SEA PICTURES, OP.37 1. Sea Slumber-Song (Roden Noel) .......................................................... 5.15 2. In Haven (C. Alice Elgar) ........................................................................... 1.42 3. Sabbath Morning at Sea (Mrs Browning) ........................................ 5.47 4. Where Corals Lie (Dr Richard Garnett) ............................................. 3.57 5. The Swimmer (Adam Lindsay Gordon) .............................................5.52 ALICE COOTE MEZZO SOPRANO 6. POLONIA, OP.76 ......................................................................................13.16 POMP AND CIRCUMSTANCE MARCHES, OP.39 7. No.1 in D major .............................................................................................. 6.14 8. No.2 in A minor .............................................................................................. 5.14 9. No.3 in C minor ..............................................................................................5.49 10. No.4 in G major ..............................................................................................4.52 11. No.5 in C major .............................................................................................. 6.15 TOTAL TIMING .....................................................................................................64.58 ≥ MUSIC DIRECTOR SIR MARK ELDER CBE LEADER LYN FLETCHER WWW.HALLE.CO.UK -

Sir John Eliot Gardiner Conductor Stravinsky Symphony in Three Movements = 160 Andante—Interlude:Q L’Istesso Tempo— Con Moto Elgar in the South (Alassio), Op

Program OnE HundrEd TwEnTIETH SEASOn Chicago Symphony orchestra riccardo muti Music director Pierre Boulez Helen regenstein Conductor Emeritus Yo-Yo ma Judson and Joyce Green Creative Consultant Global Sponsor of the CSO Thursday, January 20, 2011, at 8:00 Saturday, January 22, 2011, at 8:00 Sir John Eliot gardiner Conductor Stravinsky Symphony in Three Movements = 160 Andante—Interlude:q L’istesso tempo— Con moto Elgar In the South (Alassio), Op. 50 IntErmISSIon Bartók Concerto for Orchestra Introduzione: Andante non troppo—Allegro vivace Giuoco delle coppie: Allegro scherzando Elegia: Andante non troppo Intermezzo interrotto: Allegretto Finale: Presto Steinway is the official piano of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. This program is partially supported by grants from the Illinois Arts Council, a state agency, and the National Endowment for the Arts. CommEntS by PHILLIP HuSCHEr Igor Stravinsky Born June 18, 1882, Oranienbaum, Russia. Died April 6, 1971, New York City. Symphony in three movements o composer has given us more Stravinsky is again playing word Nperspectives on a “symphony” games. (And, perhaps, as has than Stravinsky. He wrote a sym- been suggested, he used the term phony at the very beginning of his partly to placate his publisher, who career (it’s his op. 1), but Stravinsky reminded him, after the score was quickly became famous as the finished, that he had been com- composer of three ballet scores missioned to write a symphony.) (Petrushka, The Firebird, and The Rite Then, at last, a true symphony: in of Spring), and he spent the next few 1938, Mrs. Robert Woods Bliss, years composing for the theater and together with Mrs. -

Scouting Games. 61 Horse and Rider 54 1

The MacScouter's Big Book of Games Volume 2: Games for Older Scouts Compiled by Gary Hendra and Gary Yerkes www.macscouter.com/Games Table of Contents Title Page Title Page Introduction 1 Radio Isotope 11 Introduction to Camp Games for Older Rat Trap Race 12 Scouts 1 Reactor Transporter 12 Tripod Lashing 12 Camp Games for Older Scouts 2 Map Symbol Relay 12 Flying Saucer Kim's 2 Height Measuring 12 Pack Relay 2 Nature Kim's Game 12 Sloppy Camp 2 Bombing The Camp 13 Tent Pitching 2 Invisible Kim's 13 Tent Strik'n Contest 2 Kim's Game 13 Remote Clove Hitch 3 Candle Relay 13 Compass Course 3 Lifeline Relay 13 Compass Facing 3 Spoon Race 14 Map Orienteering 3 Wet T-Shirt Relay 14 Flapjack Flipping 3 Capture The Flag 14 Bow Saw Relay 3 Crossing The Gap 14 Match Lighting 4 Scavenger Hunt Games 15 String Burning Race 4 Scouting Scavenger Hunt 15 Water Boiling Race 4 Demonstrations 15 Bandage Relay 4 Space Age Technology 16 Firemans Drag Relay 4 Machines 16 Stretcher Race 4 Camera 16 Two-Man Carry Race 5 One is One 16 British Bulldog 5 Sensational 16 Catch Ten 5 One Square 16 Caterpillar Race 5 Tape Recorder 17 Crows And Cranes 5 Elephant Roll 6 Water Games 18 Granny's Footsteps 6 A Little Inconvenience 18 Guard The Fort 6 Slash hike 18 Hit The Can 6 Monster Relay 18 Island Hopping 6 Save the Insulin 19 Jack's Alive 7 Marathon Obstacle Race 19 Jump The Shot 7 Punctured Drum 19 Lassoing The Steer 7 Floating Fire Bombardment 19 Luck Relay 7 Mystery Meal 19 Pocket Rope 7 Operation Neptune 19 Ring On A String 8 Pyjama Relay 20 Shoot The Gap 8 Candle -

The Bayreuth Festspielhaus: the Metaphysical Manifestation of Wagner's Der Ring Des Nibelungen Matthew Timmermans University of Ottawa

Nota Bene: Canadian Undergraduate Journal of Musicology Volume 8 | Issue 1 Article 6 The Bayreuth Festspielhaus: The Metaphysical Manifestation of Wagner's Der Ring des Nibelungen Matthew Timmermans University of Ottawa Recommended Citation Timmermans, Matthew (2015) "The Bayreuth Festspielhaus: The Metaphysical Manifestation of Wagner's Der Ring des Nibelungen," Nota Bene: Canadian Undergraduate Journal of Musicology: Vol. 8: Iss. 1, Article 6. The Bayreuth Festspielhaus: The Metaphysical Manifestation of Wagner's Der Ring des Nibelungen Abstract This essay explores how the architectural design of the Bayreuth Festspielhaus effects the performance of Wagner’s later operas, specifically Der Ring des Nibelungen. Contrary to Wagner’s theoretical writings, which advocate equality among the various facets of operatic production (Gesamtkuntswerk), I argue that Wagner’s architectural design elevates music above these other art forms. The evidence lies within the unique architecture of the house, which Wagner constructed to realize his operatic vision. An old conception of Wagnerian performance advocated by Cosima Wagner—in interviews and letters—was consciously left by Richard Wagner. However, I juxtapose this with Daniel Barenboim’s modern interpretation, which suggests that Wagner unconsciously, or by a Will beyond himself, created Bayreuth as more than the legacy he passed on. The juxtaposition parallels the revolutionary nature of Wagner’s ideas embedded in Bayreuth’s architecture. To underscore this revolution, I briefly outline Wagner’s philosophical development, specifically the ideas he extracted from the works of Ludwig Feuerbach and Arthur Schopenhauer, further defining the focus of Wagner’s composition and performance of the music. The analysis thereby challenges the prevailing belief that Wagner intended Bayreuth and Der Ring des Nibelungen, the opera which inspired the house’s inception, to embody Gesamtkunstwerk; instead, these creations internalize the drama, allowing the music to reign supreme. -

Vol. 17, No. 3 December 2011

Journal December 2011 Vol.17, No. 3 The Elgar Society Journal The Society 18 Holtsmere Close, Watford, Herts., WD25 9NG Email: [email protected] December 2011 Vol. 17, No. 3 President Editorial 3 Julian Lloyd Webber FRCM Gerald Lawrence, Elgar and the missing Beau Brummel Music 4 Vice-Presidents Robert Kay Ian Parrott Sir David Willcocks, CBE, MC Elgar and Rosa Newmarch 29 Diana McVeagh Martin Bird Michael Kennedy, CBE Michael Pope Book reviews Sir Colin Davis, CH, CBE Robert Anderson, Martin Bird, Richard Wiley 41 Dame Janet Baker, CH, DBE Leonard Slatkin Music reviews 46 Sir Andrew Davis, CBE Simon Thompson Donald Hunt, OBE Christopher Robinson, CVO, CBE CD reviews 49 Andrew Neill Barry Collett, Martin Bird, Richard Spenceley Sir Mark Elder, CBE 100 Years Ago 61 Chairman Steven Halls Vice-Chairman Stuart Freed Treasurer Peter Hesham Secretary The Editor does not necessarily agree with the views expressed by contributors, Helen Petchey nor does the Elgar Society accept responsibility for such views. Front Cover: Gerald Lawrence in his Beau Brummel costume, from Messrs. William Elkin's published piano arrangement of the Minuet (Arthur Reynolds Collection). Notes for Contributors. Please adhere to these as far as possible if you deliver writing (as is much preferred) in Microsoft Word or Rich Text Format. A longer version is available in case you are prepared to do the formatting, but for the present the editor is content to do this. Copyright: it is the contributor’s responsibility to be reasonably sure that copyright permissions, if Editorial required, are obtained. Illustrations (pictures, short music examples) are welcome, but please ensure they are pertinent, cued into the text, and have captions. -

Chanson De Nuit Op 15 for Guitar Duo Sheet Music

Chanson De Nuit Op 15 For Guitar Duo Sheet Music Download chanson de nuit op 15 for guitar duo sheet music pdf now available in our library. We give you 2 pages partial preview of chanson de nuit op 15 for guitar duo sheet music that you can try for free. This music notes has been read 2817 times and last read at 2021-10-01 09:55:44. In order to continue read the entire sheet music of chanson de nuit op 15 for guitar duo you need to signup, download music sheet notes in pdf format also available for offline reading. Instrument: Classical Guitar Ensemble: Mixed Level: Advanced [ READ SHEET MUSIC ] Other Sheet Music Chanson De Nuit And Chanson De Matin Op 15 For Guitar Duo Chanson De Nuit And Chanson De Matin Op 15 For Guitar Duo sheet music has been read 3664 times. Chanson de nuit and chanson de matin op 15 for guitar duo arrangement is for Advanced level. The music notes has 6 preview and last read at 2021-10-01 10:42:32. [ Read More ] Chanson De Nuit And Chanson De Matin Op 15 For Cello And Guitar Chanson De Nuit And Chanson De Matin Op 15 For Cello And Guitar sheet music has been read 3488 times. Chanson de nuit and chanson de matin op 15 for cello and guitar arrangement is for Advanced level. The music notes has 5 preview and last read at 2021-10-01 09:55:06. [ Read More ] Chanson De Nuit And Chanson De Matin Op 15 For Flute And Guitar Chanson De Nuit And Chanson De Matin Op 15 For Flute And Guitar sheet music has been read 6579 times. -

BRITISH and COMMONWEALTH CONCERTOS from the NINETEENTH CENTURY to the PRESENT Sir Edward Elgar

BRITISH AND COMMONWEALTH CONCERTOS FROM THE NINETEENTH CENTURY TO THE PRESENT A Discography of CDs & LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Sir Edward Elgar (1857-1934) Born in Broadheath, Worcestershire, Elgar was the son of a music shop owner and received only private musical instruction. Despite this he is arguably England’s greatest composer some of whose orchestral music has traveled around the world more than any of his compatriots. In addition to the Conceros, his 3 Symphonies and Enigma Variations are his other orchestral masterpieces. His many other works for orchestra, including the Pomp and Circumstance Marches, Falstaff and Cockaigne Overture have been recorded numerous times. He was appointed Master of the King’s Musick in 1924. Piano Concerto (arranged by Robert Walker from sketches, drafts and recordings) (1913/2004) David Owen Norris (piano)/David Lloyd-Jones/BBC Concert Orchestra ( + Four Songs {orch. Haydn Wood}, Adieu, So Many True Princesses, Spanish Serenade, The Immortal Legions and Collins: Elegy in Memory of Edward Elgar) DUTTON EPOCH CDLX 7148 (2005) Violin Concerto in B minor, Op. 61 (1909-10) Salvatore Accardo (violin)/Richard Hickox/London Symphony Orchestra ( + Walton: Violin Concerto) BRILLIANT CLASSICS 9173 (2010) (original CD release: COLLINS CLASSICS COL 1338-2) (1992) Hugh Bean (violin)/Sir Charles Groves/Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra ( + Violin Sonata, Piano Quintet, String Quartet, Concert Allegro and Serenade) CLASSICS FOR PLEASURE CDCFP 585908-2 (2 CDs) (2004) (original LP release: HMV ASD2883) (1973) -

Music Written for Piano and Violin

Music written for piano and violin: Title Year Approx. Length Allegretto on GEDGE 1885 4 mins 30 secs Bizarrerie 1889 2 mins 30 secs La Capricieuse 1891 4 mins 30 secs Gavotte 1885 4 mins 30 secs Une Idylle 1884 3 mins 30 secs May Song 1901 3 mins 45 secs Offertoire 1902 4 mins 30 secs Pastourelle 1883 3 mins 00 secs Reminiscences 1877 3 mins 00 secs Romance 1878 5 mins 30 secs Virelai 1883 3 mins 00 secs Publishers survive by providing the public with works they wish to buy. And a struggling composer, if he wishes his music to be published and therefore reach a wider audience, must write what a publisher believes he can sell. Only having established a reputation can a composer write larger scale works in a form of his own choosing with any realistic expectation of having them performed. During the latter half of the nineteenth century, the stock-in-trade for most publishers was the sale of sheet music of short salon pieces for home performance. It was a form that was eventually to bring Elgar considerably enhanced recognition and a degree of financial success with the publication for solo piano of Salut d'Amour in 1888 and of three hugely popular works first published in arrangements for piano and violin - Mot d'Amour (1889), Chanson de Nuit (1897) and Chanson de Matin (1899). Elgar composed short pieces for solo piano sporadically throughout his life. But, apart from the two Chansons, May Song (1901) and Offertoire (1902), an arrangement of Sospiri and, of course, the Violin Sonata, all of Elgar's works for piano and violin were composed between 1877, the dawning of his ambitions to become a serious composer, and 1891, the year after his first significant orchestral success withFroissart. -

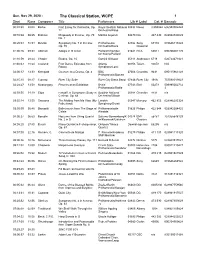

29, 2020 - the Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title Performerslib # Label Cat

Sun, Nov 29, 2020 - The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title PerformersLIb # Label Cat. # Barcode 00:01:30 08:08 Barber First Essay for Orchestra, Op. Royal Scottish National 08830 Naxos 8.559024 636943902424 12 Orchestra/Alsop 00:10:3808:25 Brahms Rhapsody in B minor, Op. 79 Martha Argerich 04470 DG 447 430 028944743029 No. 1 00:20:03 38:53 Dvorak Symphony No. 7 in D minor, Philharmonia 02982 Sony 67174 074646717424 Op. 70 Orchestra/Davis Classical 01:00:2609:33 Albinoni Adagio in G minor Paillard Chamber 01641 RCA 60011 090266001125 Orchestra/Paillard 01:10:59 28:44 Chopin Etudes, Op. 10 Garrick Ohlsson 05311 Arabesque 6718 026724671821 01:40:4318:24 Copland Four Dance Episodes from Atlanta 00356 Telarc 80078 N/A Rodeo Symphony/Lane 02:00:3713:33 Korngold Overture to a Drama, Op. 4 BBC 07006 Chandos 9631 095115963128 Philharmonic/Bamert 02:15:1008:17 Curnow River City Suite River City Brass Band 07846 River City 198A 753598019823 02:24:2733:58 Mussorgsky Pictures at an Exhibition Berlin 07743 EMI 00273 509995002732 Philharmonic/Rattle 3 02:59:55 34:19 Elgar Falstaff, A Symphonic Study in Scottish National 00988 Chandos 8431 n/a C minor, Op. 68 Orchestra/Gibson 03:35:1413:55 Smetana The Moldau from Ma Vlast (My London 05047 Mercury 462 953 028946295328 Fatherland) Symphony/Dorati 03:50:09 08:48 Donizetti Ballet music from The Siege of Philharmonia/de 01826 Philips 422 844 028942284425 Calais Almeida 04:00:2706:53 Borodin Nocturne from String Quartet Salerno-Sonnenberg/K 04974 EMI 56481 724355648129 No. -

A History of Rhythm, Metronomes, and the Mechanization of Musicality

THE METRONOMIC PERFORMANCE PRACTICE: A HISTORY OF RHYTHM, METRONOMES, AND THE MECHANIZATION OF MUSICALITY by ALEXANDER EVAN BONUS A DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Music CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY May, 2010 CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES We hereby approve the thesis/dissertation of _____________________________________________________Alexander Evan Bonus candidate for the ______________________Doctor of Philosophy degree *. Dr. Mary Davis (signed)_______________________________________________ (chair of the committee) Dr. Daniel Goldmark ________________________________________________ Dr. Peter Bennett ________________________________________________ Dr. Martha Woodmansee ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ (date) _______________________2/25/2010 *We also certify that written approval has been obtained for any proprietary material contained therein. Copyright © 2010 by Alexander Evan Bonus All rights reserved CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES . ii LIST OF TABLES . v Preface . vi ABSTRACT . xviii Chapter I. THE HUMANITY OF MUSICAL TIME, THE INSUFFICIENCIES OF RHYTHMICAL NOTATION, AND THE FAILURE OF CLOCKWORK METRONOMES, CIRCA 1600-1900 . 1 II. MAELZEL’S MACHINES: A RECEPTION HISTORY OF MAELZEL, HIS MECHANICAL CULTURE, AND THE METRONOME . .112 III. THE SCIENTIFIC METRONOME . 180 IV. METRONOMIC RHYTHM, THE CHRONOGRAPHIC -

INTRODUCTION 1. in Explanation of His Point, Sperry Writes: 'It Is Not Just

Notes INTRODUCTION 1. In explanation of his point, Sperry writes: 'It is not just that the poetry is taken up in isolation from the life of the poet, from the deeper logic of his career both in itself and in relation to the history of his times, although that fact is continuously disconcerting. It is further that in reducing the verse to a structure of ideas, criticism has gone far toward depriving it of all emotional reality'(14). 2. See, in particular, Federico Olivero's essays on Shelley and Ve nice (1909: 217-25), Shelley and Dante, Petrarch and the Italian countryside (1913: 123-76), Epipsychidion (1918: 379-92), Shelley and Turner (1935); Corrado Zacchetti's Shelley e Dante (1922); and Maria De Courten's Percy Bysshe Shelley e l'Italia (1923). A more recent, and important, work is Aurelio Zanco's monograph, Shelley e l'Italia (1945). Other studies of note are by Tirinelli (1893); Fontanarosa (1897); Bernheimer (1920); Bini (1927); and Viviani della Robbia (1936). 3. In researching this field of study, Italian critics have found Shelley to be their best spokesman. 4. A work such as Anna Benneson McMahan's With Shelley in Italy (1907) comes to mind. Hers is a more inclusive anthology than John Lehmann's Shelley in Italy (1947) but needs to be brought up to date. 5. There has been a growing recognition of the importance of the Italian element in Shelley's poetry. Significant studies in English since those of Scudder (1895: 96-114), Toynbee (1909: 214-30), Bradley (1914: 441-56) and Stawell (1914: 104-31) are those of P.