Vol.21 No 2 August 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ARSC Journal

A Discography of the Choral Symphony by J. F. Weber In previous issues of this Journal (XV:2-3; XVI:l-2), an effort was made to compile parts of a composer discography in depth rather than breadth. This one started in a similar vein with the realization that SO CDs of the Beethoven Ninth Symphony had been released (the total is now over 701). This should have been no surprise, for writers have stated that the playing time of the CD was designed to accommodate this work. After eighteen months' effort, a reasonably complete discography of the work has emerged. The wonder is that it took so long to collect a body of information (especially the full names of the vocalists) that had already been published in various places at various times. The Japanese discographers had made a good start, and some of their data would have been difficult to find otherwise, but quite a few corrections and additions have been made and some recording dates have been obtained that seem to have remained 1.Dlpublished so far. The first point to notice is that six versions of the Ninth didn't appear on the expected single CD. Bl:lhm (118) and Solti (96) exceeded the 75 minutes generally assumed (until recently) to be the maximum CD playing time, but Walter (37), Kegel (126), Mehta (127), and Thomas (130) were not so burdened and have been reissued on single CDs since the first CD release. On the other hand, the rather short Leibowitz (76), Toscanini (11), and Busch (25) versions have recently been issued with fillers. -

Sir John Eliot Gardiner Conductor Stravinsky Symphony in Three Movements = 160 Andante—Interlude:Q L’Istesso Tempo— Con Moto Elgar in the South (Alassio), Op

Program OnE HundrEd TwEnTIETH SEASOn Chicago Symphony orchestra riccardo muti Music director Pierre Boulez Helen regenstein Conductor Emeritus Yo-Yo ma Judson and Joyce Green Creative Consultant Global Sponsor of the CSO Thursday, January 20, 2011, at 8:00 Saturday, January 22, 2011, at 8:00 Sir John Eliot gardiner Conductor Stravinsky Symphony in Three Movements = 160 Andante—Interlude:q L’istesso tempo— Con moto Elgar In the South (Alassio), Op. 50 IntErmISSIon Bartók Concerto for Orchestra Introduzione: Andante non troppo—Allegro vivace Giuoco delle coppie: Allegro scherzando Elegia: Andante non troppo Intermezzo interrotto: Allegretto Finale: Presto Steinway is the official piano of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. This program is partially supported by grants from the Illinois Arts Council, a state agency, and the National Endowment for the Arts. CommEntS by PHILLIP HuSCHEr Igor Stravinsky Born June 18, 1882, Oranienbaum, Russia. Died April 6, 1971, New York City. Symphony in three movements o composer has given us more Stravinsky is again playing word Nperspectives on a “symphony” games. (And, perhaps, as has than Stravinsky. He wrote a sym- been suggested, he used the term phony at the very beginning of his partly to placate his publisher, who career (it’s his op. 1), but Stravinsky reminded him, after the score was quickly became famous as the finished, that he had been com- composer of three ballet scores missioned to write a symphony.) (Petrushka, The Firebird, and The Rite Then, at last, a true symphony: in of Spring), and he spent the next few 1938, Mrs. Robert Woods Bliss, years composing for the theater and together with Mrs. -

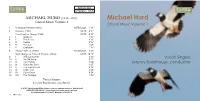

Michael Hurd

SRCD.363 STEREO DDD MICHAEL HURD (1928- 2006) Michael Hurd Choral Music Volume 1 Choral Music Volume 1 1 (1987) SATB/organ 7’54” 2 (1987) SATB 6’07” (1996) SATB 9’55” 3 I Antiphon 1’03” 4 II The Pulley 3’13” 5 III Vertue 2’47” 6 IV The Call 1’05” 7 V Exultation 1’47” 8 (1987) SATB/organ 3’00” (1994) SATB 20’14” 9 I Will you Come? 2’00” Vasari Singers 10 II An Old Song 3’12” 11 III Two Pewits 2’06” Jeremy Backhouse, conductor 12 IV Out in the Dark 3’07” 13 V The Dark Forest 2’28” 14 VI Lights Out 4’28” 15 VII Cock-Crow 0’54” 16 VIII The Trumpet 1’59” Vasari Singers Jeremy Backhouse, conductor c © 20 SRCD.363 SRCD.363 1 Michael Hurd was born in Gloucester on 19 December 1928, the son of a self- (1966) SSA/organ 11’14” employed cabinetmaker and upholsterer. His early education took place at Crypt 17 I Kyrie eleison 1’39” Grammar School in Gloucester. National Service with the Intelligence Corps involved 18 II Gloria in excelsis Deo 3’17” a posting to Vienna, where he developed a burgeoning passion for opera. He studied 19 III Sanctus 1’35” at Pembroke College, Oxford (1950-53) with Sir Thomas Armstrong and Dr Bernard 20 IV Benedictus 1’40” Rose and became President of the University Music Society. In addition, he took 21 V Agnus Dei 3’03” composition lessons from Lennox Berkeley, whose Gallic sensibility may be said to have (1980) SATB 5’39” influenced Hurd’s own musical language, not least in the attractive and witty Concerto 22 I Captivity 2’34” da Camera for oboe and small orchestra (1979), which he described in his programme 23 II Rejection 1’03” note as a homage to Poulenc’s ‘particular genius’. -

Sunday 31 January 2016 David Owen Norris, Piano & Adrian

Sunday 31 January 2016 David Owen Norris, Piano & Adrian Chandler, Violin Revised Programme Sonata for piano and violin in B flat major K378 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) Allegro Moderato Andantino sostenuto e cantabile Rondeau: Allegro – Allegro – Come prima Variations for solo piano on Robin Adair (see note) George Kiallmark (1781-1835) Andante semplice. Var:1 Gayment Var:2 Siciliano Var:3 Marcia risoluto Var:4 Brillante Var:5 A Tempo 6 variations on Hélas, j’ai perdu mon amant in G minor K360 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Sonata for fortepiano and violin in A major op 12/2 Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) Allegro vivace Andante più tosto allegretto Allegro piacevole INTERVAL Piano solo: Rondo capriccioso op 14 (Vienna, 1830) Felix Mendelssohn (1809-1847) Sonata for fortepiano and violin in F major op24 Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) Allegro Adagio molto espressivo Scherzo – Allegro molto Rondo – Allegro mà non troppo Note: Kiallmark’s Variations on Robin Adair (the only piece of music actually named in Jane Austen’s novels) appears in the novelist’s own music collection as a cherished and carefully bound print. In Emma, Frank Churchill and Emma listen to Jane Fairfax playing the new piano which Frank has anonymously presented to her: the engagement between Jane and Frank is a secret. Frank’s remarks to Emma are full of double meanings as they discuss Jane’s supposed infatuation with the married Mr. Dixon. Despite the fact that Frank says: ‘She is playing Robin Adair at this moment – his favourite’, many assume that Jane was singing as well (Peter F. -

Sunday Playlist

November 25, 2018: (Full-page version) Close Window “I was obliged to be industrious. Whoever is equally industrious will succeed equally well.” — Johann Sebastian Bach Start Buy CD Program Composer Title Performers Record Label Stock Number Barcode Time online Sleepers, Watkinson/King's Chamber 00:01 Buy Now! Handel Ombra mai fu ~ Serse (Xerxes) Sony Classical 89370 696998937024 Awake! Orchestra/Malgoire 00:05 Buy Now! Beethoven Piano Sonata No. 18 in E flat, Op. 31 No. 3 "Hunt" Wilhelm Kempff DG 429 306 n/a 00:27 Buy Now! Hanson Symphony No. 1 in E minor, Op. 21 "Nordic" Nashville Symphony/Schermerhorn Naxos 8.559072 636943907221 01:01 Buy Now! Gershwin Lullaby for String Quartet Manhattan String Quartet Newport Classics 60033 N/A 01:09 Buy Now! Bach Brandenburg Concerto No. 1 in F, BWV 1046 Il Giardino Armonico/Antonini Teldec 6019 745099844226 01:29 Buy Now! Dvorak Violin Concerto in A minor, Op. 53 Luca/Saint Louis Symphony/Slatkin Nonesuch 79052 07559790522 02:00 Buy Now! Duffy Three Jewish Portraits Milwaukee Symphony/Macal Koss Classics 1022 021299710388 String Quartet No. 14 in D minor, D. 810 "Death and the 02:11 Buy Now! Schubert Amadeus Quartet DG 410 024 028941002426 Maiden" 02:51 Buy Now! Gottschalk The Dying Poet Robert Silverman Marquis Classics 161 774718116123 03:00 Buy Now! Schumann String Quartet in A, Op. 41 No. 3 St. Lawrence String Quartet EMI 56797 724355679727 03:33 Buy Now! Foote Second Suite for Piano, Op. 30 Virginia Eskin Northeastern 223 n/a 03:47 Buy Now! Still Miniatures Powers Woodwind Quintet White Pine Music 215 700261334110 Suzuki/Orlovsky/Indianapolis 03:59 Buy Now! Canning Fantasy on a Hymn by Justin Morgan Decca 458 157 028945845725 SO/Leppard 04:11 Buy Now! Telemann Trumpet Concerto No. -

The Elgar Sketch-Books

THE ELGAR SKETCH-BOOKS PAMELA WILLETTS A MAJOR gift from Mrs H. S. Wohlfeld of sketch-books and other manuscripts of Sir Edward Elgar was received by the British Library in 1984. The sketch-books consist of five early books dating from 1878 to 1882, a small book from the late 1880s, a series of eight volumes made to Elgar's instructions in 1901, and two later books commenced in Italy in 1909.^ The collection is now numbered Add. MSS. 63146-63166 (see Appendix). The five early sketch-books are oblong books in brown paper covers. They were apparently home-made from double sheets of music-paper, probably obtained from the stock of the Elgar shop at 10 High Street, Worcester. The paper was sewn together by whatever means was at hand; volume III is held together by a gut violin string. The covers were made by the expedient of sticking brown paper of varying shades and textures to the first and last leaves of music-paper and over the spine. Book V is of slightly smaller oblong format and the sides of the music sheets in this volume have been inexpertly trimmed. The volumes bear Elgar's numbering T to 'V on the covers, his signature, and a date, perhaps that ofthe first entry in the volumes. The respective dates are: 21 May 1878(1), 13 August 1878 (II), I October 1878 (III), 7 April 1879 (IV), and i September 1881 (V). Elgar was not quite twenty-one when the first of these books was dated. Earlier music manuscripts from his hand have survived but the particular interest of these early sketch- books is in their intimate connection with the round of Elgar's musical activities, amateur and professional, at a formative stage in his career. -

Britten EU 572706Bk Britten EU 02/06/2011 12:29 Page 1

572706bk Britten EU_572706bk Britten EU 02/06/2011 12:29 Page 1 Mark Wilde David Owen Norris The tenor Mark Wilde studied at the Royal College of Music in David Owen Norris studied in Oxford, London and Paris. He was London. His rôles have included Ferrando in Così fan tutte repetiteur at the Royal Opera House, harpist at the Royal BRITTEN (Glyndebourne), Frederic in Pirates of Penzance (ENO), Shakespeare Company, Artistic Director of Festivals in Cardiff Albert Herring (Perth Festival), Il Campanello (Buxton and Petworth, Chairman of the Steans Institute for Singers in Festival), Ottone in La Serenissima (BBC Radio 3), Jacquino Chicago, and the Gresham Professor of Music in London. He is in Fidelio (Glyndebourne Touring Opera), Seven Deadly Sins currently preparing a third series of his iPod programmes for Complete Scottish Songs (WNO), Cat in Jonathan Dove’s Pinocchio (Opera North), BBC Radio 4, and his current engagements include performances A Birthday Hansel • Who are these children? Ottavio in Don Giovanni (Mostly Mozart Festival), Male in Norway, Holland, France, Taiwan, Mexico, Canada, and across Chorus in The Rape of Lucretia (European Opera Centre), the United States. His discography includes recordings of Giannetto in La gazza ladra (Garsington Opera), Rudolf in concertos by Elgar, Phillips, Arnell and Lambert, of the complete Mark Wilde, Tenor Euryanthe (Netherlands Opera), Ottavio, Alfredo in La travia- piano music of Elgar, Quilter and Dyson, Jane Austen’s music ta, Candide, and Idamante in Idomeneo (Birmingham Opera), collection, and many song collections, including the première Lucy Wakeford, Harp • David Owen Norris, Piano Count Almaviva in The Barber of Seville (Savoy Theatre Photo: www.simonweir.com recording of Schubert’s first song-cycle, the Kosegarten Opera), Adelaide de Borgogna (Edinburgh International Liederspiel, and of Elgar’s last song. -

BRITISH and COMMONWEALTH CONCERTOS from the NINETEENTH CENTURY to the PRESENT Sir Edward Elgar

BRITISH AND COMMONWEALTH CONCERTOS FROM THE NINETEENTH CENTURY TO THE PRESENT A Discography of CDs & LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Sir Edward Elgar (1857-1934) Born in Broadheath, Worcestershire, Elgar was the son of a music shop owner and received only private musical instruction. Despite this he is arguably England’s greatest composer some of whose orchestral music has traveled around the world more than any of his compatriots. In addition to the Conceros, his 3 Symphonies and Enigma Variations are his other orchestral masterpieces. His many other works for orchestra, including the Pomp and Circumstance Marches, Falstaff and Cockaigne Overture have been recorded numerous times. He was appointed Master of the King’s Musick in 1924. Piano Concerto (arranged by Robert Walker from sketches, drafts and recordings) (1913/2004) David Owen Norris (piano)/David Lloyd-Jones/BBC Concert Orchestra ( + Four Songs {orch. Haydn Wood}, Adieu, So Many True Princesses, Spanish Serenade, The Immortal Legions and Collins: Elegy in Memory of Edward Elgar) DUTTON EPOCH CDLX 7148 (2005) Violin Concerto in B minor, Op. 61 (1909-10) Salvatore Accardo (violin)/Richard Hickox/London Symphony Orchestra ( + Walton: Violin Concerto) BRILLIANT CLASSICS 9173 (2010) (original CD release: COLLINS CLASSICS COL 1338-2) (1992) Hugh Bean (violin)/Sir Charles Groves/Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra ( + Violin Sonata, Piano Quintet, String Quartet, Concert Allegro and Serenade) CLASSICS FOR PLEASURE CDCFP 585908-2 (2 CDs) (2004) (original LP release: HMV ASD2883) (1973) -

Music Written for Piano and Violin

Music written for piano and violin: Title Year Approx. Length Allegretto on GEDGE 1885 4 mins 30 secs Bizarrerie 1889 2 mins 30 secs La Capricieuse 1891 4 mins 30 secs Gavotte 1885 4 mins 30 secs Une Idylle 1884 3 mins 30 secs May Song 1901 3 mins 45 secs Offertoire 1902 4 mins 30 secs Pastourelle 1883 3 mins 00 secs Reminiscences 1877 3 mins 00 secs Romance 1878 5 mins 30 secs Virelai 1883 3 mins 00 secs Publishers survive by providing the public with works they wish to buy. And a struggling composer, if he wishes his music to be published and therefore reach a wider audience, must write what a publisher believes he can sell. Only having established a reputation can a composer write larger scale works in a form of his own choosing with any realistic expectation of having them performed. During the latter half of the nineteenth century, the stock-in-trade for most publishers was the sale of sheet music of short salon pieces for home performance. It was a form that was eventually to bring Elgar considerably enhanced recognition and a degree of financial success with the publication for solo piano of Salut d'Amour in 1888 and of three hugely popular works first published in arrangements for piano and violin - Mot d'Amour (1889), Chanson de Nuit (1897) and Chanson de Matin (1899). Elgar composed short pieces for solo piano sporadically throughout his life. But, apart from the two Chansons, May Song (1901) and Offertoire (1902), an arrangement of Sospiri and, of course, the Violin Sonata, all of Elgar's works for piano and violin were composed between 1877, the dawning of his ambitions to become a serious composer, and 1891, the year after his first significant orchestral success withFroissart. -

To Download the Full Archive

Complete Concerts and Recording Sessions Brighton Festival Chorus 27 Apr 1968 Concert Dome Concert Hall, Brighton Brighton Festival Belshazzar's Feast Walton William Walton Royal Philharmonic Orchestra Baritone Thomas Hemsley 11 May 1968 Concert Dome Concert Hall, Brighton Brighton Festival Kyrie in D minor, K 341 Mozart Colin Davis BBC Symphony Orchestra 27 Oct 1968 Concert Dome Concert Hall, Brighton Brighton Philharmonic Society Budavari Te Deum Kodály Laszlo Heltay Brighton Philharmonic Orchestra Soprano Doreen Price Mezzo-Soprano Sarah Walker Tenor Paul Taylor Bass Brian Kay 23 Feb 1969 Concert Dome Concert Hall, Brighton Brighton Philharmonic Society Symphony No. 9 in D minor, op.125 Beethoven Herbert Menges Brighton Philharmonic Orchestra Soprano Elizabeth Harwood Mezzo-Soprano Barbara Robotham Tenor Kenneth MacDonald Bass Raimund Herincx 09 May 1969 Concert Dome Concert Hall, Brighton Brighton Festival Mass in D Dvorák Václav Smetáček Czech Philharmonic Orchestra Soprano Doreen Price Mezzo-Soprano Valerie Baulard Tenor Paul Taylor Bass Michael Rippon Sussex University Choir 11 May 1969 Concert Dome Concert Hall, Brighton Brighton Festival Liebeslieder-Walzer Brahms Laszlo Heltay Piano Courtney Kenny Piano Roy Langridge 25 Jan 1970 Concert Dome Concert Hall, Brighton Brighton Philharmonic Society Requiem Fauré Laszlo Heltay Brighton Philharmonic Orchestra Soprano Maureen Keetch Baritone Robert Bateman Organ Roy Langridge 09 May 1970 Concert Dome Concert Hall, Brighton Brighton Festival Mass in B Minor Bach Karl Richter English Chamber Orchestra Soprano Ann Pashley Mezzo-Soprano Meriel Dickinson Tenor Paul Taylor Bass Stafford Dean Bass Michael Rippon Sussex University Choir 1 Brighton Festival Chorus 17 May 1970 Concert Dome Concert Hall, Brighton Brighton Festival Fantasia for Piano, Chorus and Orchestra in C minor Beethoven Symphony No. -

David Owen Norris Biography Biography Piano

Ikon Arts Management Ltd Suite 114, Business Design Centre 52 Upper St reet , London N1 0QH t: +44 (0)20 7354 9199 f: +44 (0)870 130 9646 [email protected] www.ikonarts.com David Owen Norris Biography Piano “quite possibly the most interesting pianist in the world” Globe & Mail, Toronto Website www. davidowennorris.com Contact Jessica Hill Email jessica @ikonarts.com David Owen Norris is one of the most innovative and brilliant pianists of our generation, being an authority and leading p erformer on early pianos, rare piano concertos (especially those by 20th century English composers), as well as being the pianist of choice for many world class singers. His work as a concert pianist has taken him round the world for forty years – ‘quite possibly the most interesting pianist in the world!’ says the Toronto Globe & Mail , while his latest piano solo CD got a double five star review in BBC Music Magazine in the spring. He was the first winner of the Gilmore Artist Award. David Owen Norris’s Symphony was premiered in 2013, and he’s just revised his Piano Concerto: there are plans to record both in January 2015, for broadcast and commercial CD. His cantata, STERNE, was THE MAN, commissioned to mark the tercentenary of the experimental novelist Laurence Sterne, was premiered in York Minster last autumn, and receives more performances later this month at Winchester College and Poole Parish Church. Norris’s song cycle Think only this, to poetry of the Great War, will be performed in the Turner Sim s at Southampton in November. -

CHAN 6652 BOOK.Qxd 22/5/07 4:33 Pm Page 2

CHAN 6652 Cover.qxd 22/5/07 4:31 pm Page 1 CHAN 6652 CHAN 6652 BOOK.qxd 22/5/07 4:33 pm Page 2 Sir Edward Elgar (1857–1934) Elgar: Overtures 1 Froissart, Op. 19 13:48 Concert Overture In his essay on Elgar’s In the South, Donald end of his life, Elgar retained an affection for Tovey, Reid Professor at Edinburgh University Froissart, his first orchestral work of real 2 Cockaigne (In London Town), Op. 40 14:18 and as canny a practical musician as he was a significance. ‘It is difficult to believe that I Concert Overture theorist, writes of conducting the overture wrote it in 1890!’ he exclaimed with typical with a student orchestra: ingenuousness to Fred Gaisberg of His 3 In the South (Alassio), Op. 50 20:32 I shall not easily forget my impression when, on Master’s Voice after recording the overture in Concert Overture first attacking [it] with considerable fear and February 1933, ‘it sounds so brilliant and expectation of its being as difficult as it is fresh.’ Incentive to write it had come in the George Frideric Handel (1685–1759) – brilliant, I found that it simply carried the form of a commission from the Worcester orchestra away with it, and seemed to play itself Festival – a faintly ironic stroke of luck, since Sir Edward Elgar at the first rehearsal. On inquiry, I found that one Elgar, born in Broadheath, had recently settled single member of the orchestra was not reading it in London. Things had at last started to look 4 Overture in D minor (1923) 5:13 at sight… I and my students had never had a up for this son of a local piano tuner.