Vol. 14, No. 4 March 2006

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ONYX4206.Pdf

EDWARD ELGAR (1857–1934) Sea Pictures Op.37 The Music Makers Op.69 (words by Alfred O’Shaughnessy) 1 Sea Slumber Song 5.13 (words by Roden Noel) 6 Introduction 3.19 2 In Haven (Capri) 1.52 7 We are the music makers 3.56 (words by Alice Elgar) 8 We, in the ages lying 3.59 3 Sabbath Morning at Sea 5.24 (words by Elizabeth Barrett Browning) 9 A breath of our inspiration 4.18 4 Where Corals Lie 3.43 10 They had no vision amazing 7.41 (words by Richard Garnett) 11 But we, with our dreaming 5 The Swimmer 5.50 and singing 3.27 (words by Adam Lindsay Gordon) 12 For we are afar with the dawning 2.25 Kathryn Rudge mezzo-soprano 13 All hail! we cry to Royal Liverpool Philharmonic the corners 9.11 Orchestra & Choir Vasily Petrenko Pomp & Circumstance 14 March No.1 Op.39/1 5.40 Total timing: 66.07 Artist biographies can be found at onyxclassics.com EDWARD ELGAR Nowadays any listener can make their own analysis as the Second Symphony, Violin Sea Pictures Op.37 · The Music Makers Op.69 Concerto and a brief quotation from The Apostles are subtly used by Elgar to point a few words in the text. Otherwise, the most powerful quotations are from The Dream On 5 October 1899, the first performance of Elgar’s song cycle Sea Pictures took place in of Gerontius, the Enigma Variations and his First Symphony. The orchestral introduction Norwich. With the exception of Elizabeth Barrett Browning, all the poets whose texts Elgar begins in F minor before the ‘Enigma’ theme emphasises, as Elgar explained to Newman, set in the works on this album would be considered obscure -

A Culture of Recording: Christopher Raeburn and the Decca Record Company

A Culture of Recording: Christopher Raeburn and the Decca Record Company Sally Elizabeth Drew A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Sheffield Faculty of Arts and Humanities Department of Music This work was supported by the Arts & Humanities Research Council September 2018 1 2 Abstract This thesis examines the working culture of the Decca Record Company, and how group interaction and individual agency have made an impact on the production of music recordings. Founded in London in 1929, Decca built a global reputation as a pioneer of sound recording with access to the world’s leading musicians. With its roots in manufacturing and experimental wartime engineering, the company developed a peerless classical music catalogue that showcased technological innovation alongside artistic accomplishment. This investigation focuses specifically on the contribution of the recording producer at Decca in creating this legacy, as can be illustrated by the career of Christopher Raeburn, the company’s most prolific producer and specialist in opera and vocal repertoire. It is the first study to examine Raeburn’s archive, and is supported with unpublished memoirs, private papers and recorded interviews with colleagues, collaborators and artists. Using these sources, the thesis considers the history and functions of the staff producer within Decca’s wider operational structure in parallel with the personal aspirations of the individual in exerting control, choice and authority on the process and product of recording. Having been recruited to Decca by John Culshaw in 1957, Raeburn’s fifty-year career spanned seminal moments of the company’s artistic and commercial lifecycle: from assisting in exploiting the dramatic potential of stereo technology in Culshaw’s Ring during the 1960s to his serving as audio producer for the 1990 The Three Tenors Concert international phenomenon. -

The Elgar Sketch-Books

THE ELGAR SKETCH-BOOKS PAMELA WILLETTS A MAJOR gift from Mrs H. S. Wohlfeld of sketch-books and other manuscripts of Sir Edward Elgar was received by the British Library in 1984. The sketch-books consist of five early books dating from 1878 to 1882, a small book from the late 1880s, a series of eight volumes made to Elgar's instructions in 1901, and two later books commenced in Italy in 1909.^ The collection is now numbered Add. MSS. 63146-63166 (see Appendix). The five early sketch-books are oblong books in brown paper covers. They were apparently home-made from double sheets of music-paper, probably obtained from the stock of the Elgar shop at 10 High Street, Worcester. The paper was sewn together by whatever means was at hand; volume III is held together by a gut violin string. The covers were made by the expedient of sticking brown paper of varying shades and textures to the first and last leaves of music-paper and over the spine. Book V is of slightly smaller oblong format and the sides of the music sheets in this volume have been inexpertly trimmed. The volumes bear Elgar's numbering T to 'V on the covers, his signature, and a date, perhaps that ofthe first entry in the volumes. The respective dates are: 21 May 1878(1), 13 August 1878 (II), I October 1878 (III), 7 April 1879 (IV), and i September 1881 (V). Elgar was not quite twenty-one when the first of these books was dated. Earlier music manuscripts from his hand have survived but the particular interest of these early sketch- books is in their intimate connection with the round of Elgar's musical activities, amateur and professional, at a formative stage in his career. -

BRITISH and COMMONWEALTH CONCERTOS from the NINETEENTH CENTURY to the PRESENT Sir Edward Elgar

BRITISH AND COMMONWEALTH CONCERTOS FROM THE NINETEENTH CENTURY TO THE PRESENT A Discography of CDs & LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Sir Edward Elgar (1857-1934) Born in Broadheath, Worcestershire, Elgar was the son of a music shop owner and received only private musical instruction. Despite this he is arguably England’s greatest composer some of whose orchestral music has traveled around the world more than any of his compatriots. In addition to the Conceros, his 3 Symphonies and Enigma Variations are his other orchestral masterpieces. His many other works for orchestra, including the Pomp and Circumstance Marches, Falstaff and Cockaigne Overture have been recorded numerous times. He was appointed Master of the King’s Musick in 1924. Piano Concerto (arranged by Robert Walker from sketches, drafts and recordings) (1913/2004) David Owen Norris (piano)/David Lloyd-Jones/BBC Concert Orchestra ( + Four Songs {orch. Haydn Wood}, Adieu, So Many True Princesses, Spanish Serenade, The Immortal Legions and Collins: Elegy in Memory of Edward Elgar) DUTTON EPOCH CDLX 7148 (2005) Violin Concerto in B minor, Op. 61 (1909-10) Salvatore Accardo (violin)/Richard Hickox/London Symphony Orchestra ( + Walton: Violin Concerto) BRILLIANT CLASSICS 9173 (2010) (original CD release: COLLINS CLASSICS COL 1338-2) (1992) Hugh Bean (violin)/Sir Charles Groves/Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra ( + Violin Sonata, Piano Quintet, String Quartet, Concert Allegro and Serenade) CLASSICS FOR PLEASURE CDCFP 585908-2 (2 CDs) (2004) (original LP release: HMV ASD2883) (1973) -

Music Written for Piano and Violin

Music written for piano and violin: Title Year Approx. Length Allegretto on GEDGE 1885 4 mins 30 secs Bizarrerie 1889 2 mins 30 secs La Capricieuse 1891 4 mins 30 secs Gavotte 1885 4 mins 30 secs Une Idylle 1884 3 mins 30 secs May Song 1901 3 mins 45 secs Offertoire 1902 4 mins 30 secs Pastourelle 1883 3 mins 00 secs Reminiscences 1877 3 mins 00 secs Romance 1878 5 mins 30 secs Virelai 1883 3 mins 00 secs Publishers survive by providing the public with works they wish to buy. And a struggling composer, if he wishes his music to be published and therefore reach a wider audience, must write what a publisher believes he can sell. Only having established a reputation can a composer write larger scale works in a form of his own choosing with any realistic expectation of having them performed. During the latter half of the nineteenth century, the stock-in-trade for most publishers was the sale of sheet music of short salon pieces for home performance. It was a form that was eventually to bring Elgar considerably enhanced recognition and a degree of financial success with the publication for solo piano of Salut d'Amour in 1888 and of three hugely popular works first published in arrangements for piano and violin - Mot d'Amour (1889), Chanson de Nuit (1897) and Chanson de Matin (1899). Elgar composed short pieces for solo piano sporadically throughout his life. But, apart from the two Chansons, May Song (1901) and Offertoire (1902), an arrangement of Sospiri and, of course, the Violin Sonata, all of Elgar's works for piano and violin were composed between 1877, the dawning of his ambitions to become a serious composer, and 1891, the year after his first significant orchestral success withFroissart. -

Aucott House, 54 Worcester Road, Malvern, Worcestershire, WR14

Aucott House, 54 Worcester Road, Malvern, Worcestershire, WR14 4AB Located within a short walk of Great Malvern, the property offers generous Second Floor Apartment Living with Three bedrooms, Two reception rooms, feature exposed ceiling timbers, Balcony with exceptional views, allocated parking and good security. £168,500 www.platinum-property.co.uk Guide Price PLATINUM PROPERTY AGENTS 253 Worcester Road, Malvern, WR14 1AA T: 01684 898800 F: 01684 568645 Email: [email protected] Property Location Malvern is a picturesque spa town situated on and around the foot hills of the Malvern Hills famous for its pure spring water and composer Sir Edward Elgar. The settlements of Malvern include Great Malvern (with Barnards Green and Poolbrook), Malvern Link (with Link Top), Malvern Wells, West Malvern, Little Malvern and North Malvern with many of these areas separated by open common land. Malvern offers two train stations, a good selection of local and high street shops and restaurants, several supermarkets and a Retail Park, Great Malvern has a library, its own nationally renowned theatre with cinema, historical Priory and a swimming pool/ fitness centre. An excellent selection of well renowned State and Private Primary and Secondary Schools can be found and good access to the M5/M50 motorway networks. DIRECTIONS: Leave our Malvern office and take the A449 towards Great Malvern driving past the Fire Station and Hospital situated on your right hand side. At the first set of traffic lights and with the common on your left continue straight along the Worcester Road towards Great Malvern. Continue through the second set of traffic lights past Holy Trinity Church on your right hand side. -

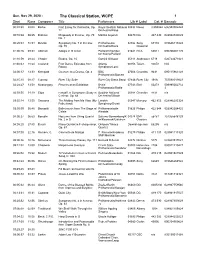

29, 2020 - the Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title Performerslib # Label Cat

Sun, Nov 29, 2020 - The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title PerformersLIb # Label Cat. # Barcode 00:01:30 08:08 Barber First Essay for Orchestra, Op. Royal Scottish National 08830 Naxos 8.559024 636943902424 12 Orchestra/Alsop 00:10:3808:25 Brahms Rhapsody in B minor, Op. 79 Martha Argerich 04470 DG 447 430 028944743029 No. 1 00:20:03 38:53 Dvorak Symphony No. 7 in D minor, Philharmonia 02982 Sony 67174 074646717424 Op. 70 Orchestra/Davis Classical 01:00:2609:33 Albinoni Adagio in G minor Paillard Chamber 01641 RCA 60011 090266001125 Orchestra/Paillard 01:10:59 28:44 Chopin Etudes, Op. 10 Garrick Ohlsson 05311 Arabesque 6718 026724671821 01:40:4318:24 Copland Four Dance Episodes from Atlanta 00356 Telarc 80078 N/A Rodeo Symphony/Lane 02:00:3713:33 Korngold Overture to a Drama, Op. 4 BBC 07006 Chandos 9631 095115963128 Philharmonic/Bamert 02:15:1008:17 Curnow River City Suite River City Brass Band 07846 River City 198A 753598019823 02:24:2733:58 Mussorgsky Pictures at an Exhibition Berlin 07743 EMI 00273 509995002732 Philharmonic/Rattle 3 02:59:55 34:19 Elgar Falstaff, A Symphonic Study in Scottish National 00988 Chandos 8431 n/a C minor, Op. 68 Orchestra/Gibson 03:35:1413:55 Smetana The Moldau from Ma Vlast (My London 05047 Mercury 462 953 028946295328 Fatherland) Symphony/Dorati 03:50:09 08:48 Donizetti Ballet music from The Siege of Philharmonia/de 01826 Philips 422 844 028942284425 Calais Almeida 04:00:2706:53 Borodin Nocturne from String Quartet Salerno-Sonnenberg/K 04974 EMI 56481 724355648129 No. -

Arthur William Edgar O'shaughnessy - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Arthur William Edgar O'Shaughnessy - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive www.PoemHunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive 1 Arthur William Edgar O'Shaughnessy(14 March 1844 – 30 January 1881) O'Shaughnessy was born on May 14, 1844 in London, England. At the age of seventeen he received the post of transcriber in the library of the British Museum. Two years later at the age of nineteen he was appointed to be an assistant in the natural history department, where he specialized in icthyology. However, his true passion was for literature. He published his Epic of Women in 1870, his first collection. He printed three collections of poetry between 1870 and 1874. When he was thirty he married and did not print any more volumes of poetry for the last seven years of his life. His last volume, Songs of a worker was published after his death the same year. By far the most noted of any his works are the initial lines of the Ode from his book Music and Moonlight (1874): <i>We are the music makers, And we are the dreamers of dreams, Wandering by lone sea-breakers, And sitting by desolate streams;— World-losers and world-forsakers, On whom the pale moon gleams: Yet we are the movers and shakers Of the world for ever, it seems.</i> Sir Edward Elgar set the ode to music in 1912 in his work entitled The Music Makers, Op 69. The work was dedicated to Elgar's old friend Nicholas Kilburn and the first performance took place at the Birmingham Triennial Music Festival in 1912. -

The Choral Cycle

THE CHORAL CYCLE: A CONDUCTOR‟S GUIDE TO FOUR REPRESENTATIVE WORKS A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE DOCTOR OF ARTS BY RUSSELL THORNGATE DISSERTATION ADVISORS: DR. LINDA POHLY AND DR. ANDREW CROW BALL STATE UNIVERSITY MUNCIE, INDIANA MAY 2011 Contents Permissions ……………………………………………………………………… v Introduction What Is a Choral Cycle? .............................................................................1 Statement of Purpose and Need for the Study ............................................4 Definition of Terms and Methodology .......................................................6 Chapter 1: Choral Cycles in Historical Context The Emergence of the Choral Cycle .......................................................... 8 Early Predecessors of the Choral Cycle ....................................................11 Romantic-Era Song Cycles ..................................................................... 15 Choral-like Genres: Vocal Chamber Music ..............................................17 Sacred Cyclical Choral Works of the Romantic Era ................................20 Secular Cyclical Choral Works of the Romantic Era .............................. 22 The Choral Cycle in the Twentieth Century ............................................ 25 Early Twentieth-Century American Cycles ............................................. 25 Twentieth-Century European Cycles ....................................................... 27 Later Twentieth-Century American -

The Delius Society Journal Spring 2001, Number 129

The Delius Society Journal Spring 2001, Number 129 The Delius Society (Registered Charity No. 298662) Full Membership and Institutions £20 per year UK students £10 per year US/\ and Canada US$38 per year Africa, Aust1alasia and far East £23 per year President Felix Aprahamian Vice Presidents Lionel Carley 131\, PhD Meredith Davies CBE Sir Andrew Davis CBE Vernon l Iandley MA, FRCM, D Univ (Surrey) Richard I Iickox FRCO (CHM) Lyndon Jenkins Tasmin Little f CSM, ARCM (I Ions), I Jon D. Lilt, DipCSM Si1 Charles Mackerras CBE Rodney Meadows Robc1 t Threlfall Chain11a11 Roge1 J. Buckley Trcaswc1 a11d M11111/Jrrship Src!l'taiy Stewart Winstanley Windmill Ridge, 82 Jlighgate Road, Walsall, WSl 3JA Tel: 01922 633115 Email: delius(alukonlinc.co.uk Serirta1y Squadron Lcade1 Anthony Lindsey l The Pound, Aldwick Village, West Sussex P021 3SR 'fol: 01243 824964 Editor Jane Armour-Chclu 17 Forest Close, Shawbirch, 'IC!ford, Shropshire TFS OLA Tel: 01952 408726 Email: [email protected] Website: http://www.dclius.org.uk Emnil: [email protected]. uk ISSN-0306-0373 Ch<lit man's Message............................................................................... 5 Edilot ial....................... .... .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. ... 6 ARTICLES BJigg Fair, by Robert Matthew Walker................................................ 7 Frede1ick Delius and Alf1cd Sisley, by Ray Inkslcr........... .................. 30 Limpsficld Revisited, by Stewart Winstanley....................................... 35 A Forgotten Ballet ?, by Jane Armour-Chclu -

Christopher A. Reynolds Collection of Women's Song

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt1t1nf085 No online items Inventory of the Christopher A. Reynolds Collection of Women's Song Sara Gunasekara & Jared Campbell Department of Special Collections General Library University of California, Davis Davis, CA 95616-5292 Phone: (530) 752-1621 Fax: (530) 754-5758 Email: [email protected] © 2013 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Inventory of the Christopher A. D-435 1 Reynolds Collection of Women's Song Collector: Reynolds, Christopher A. Title: Christopher A. Reynolds Collection of Women's Song Date (inclusive): circa 1800-1985 Extent: 15.3 linear feet Abstract: Christopher A. Reynolds, Professor of Music at the University of California, Davis, has identified and collected sheet music written by women composers active in North America and England. This collection contains over 3000 songs and song publications mostly published between 1850 and 1950. The collection is primarily made up of songs, but there are also many works for solo piano as well as anthems and part songs. In addition there are books written by the women song composers, a letter written by Virginia Gabriel in the 1860s, and four letters by Mrs. H.H.A. Beach to James Francis Cooke from the 1920s. Physical location: Researchers should contact Special Collections to request collections, as many are stored offsite. Repository: University of California, Davis. General Library. Dept. of Special Collections. Davis, California 95616-5292 Collection number: D-435 Language of Material: Collection materials in English Biography Christoper A. Reynolds received his PhD from Princeton University. He is Professor of Music at the University of Californa, Davis and author of Papal Patronage and the Music of St. -

Universiv Micrcsilms International

INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. Tlie sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark it is an indication that the film inspector noticed either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, or duplicate copy. Unless we meant to delete copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed, you will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part of the material being photo graphed the photographer has followed a definite method in “sectioning” the material. It is customary to begin filming at the upper left hand comer of a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. If necessary, sectioning is continued again—beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. For any illustrations that cannot be reproduced satisfactorily by xerography, photographic prints can be purchased at additional cost and tipped into your xerographic copy.