The Choral Cycle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Baroque Ensemble Program 12-6-18.Pdf

Our ensemble uses a set of baroque bows patterned after existing historic examples BYU – IDAHO DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC PRESENTS from the early 18th century. These bows are lighter, shorter, and have a slight outward curve resulting in characteristic baroque articulation -- a strong, quick down bow and a light, softer up bow, meant to emphasize the inequalities of strong and weak beats. Basso continuo refers to the preferred harmonic accompaniment used during the baroque era. From a printed bass line with a few harmonic clues indicated as numerical “figures,” musicians improvised chordal accompaniments which best fit the unique qualities of their instruments and supported the upper solo lines -- similar to the way a modern jazz rhythm section will “comp” behind a vocal or saxophone solo. This single bass line might include a colorful variety of both melodic and chord playing instruments. Tonight’s basso continuo section includes: • Harpsichord, featuring plucked brass strings across a light wood frame, resulting in a delicate, transparent tone which contrasts with the strong iron frame and hammered tone of the modern piano • Baroque style organ, using a mechanical “tracker” mechanism instead of electronics to route air to each pipe This evening’s performance features suites, sinfonia and concerti by prominent composers from the 17th and early 18th century: § The prolific Antonio Vivaldi is known for his development of three- movement concerto form. An extravagant violinist, he carried the nickname “il prete roso” (the red priest) because of his red hair. § Johann Heinrich Schmelzer was recognized in his day as Vienna's foremost violin virtuoso and a leading composer. -

Rest, Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal Danielle Van Oort [email protected]

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar Theses, Dissertations and Capstones 2016 Rest, Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal Danielle Van Oort [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://mds.marshall.edu/etd Part of the European History Commons, History of Religion Commons, and the Music Commons Recommended Citation Van Oort, Danielle, "Rest, Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal" (2016). Theses, Dissertations and Capstones. Paper 1016. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses, Dissertations and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. REST, SWEET NYMPHS: PASTORAL ORIGINS OF THE ENGLISH MADRIGAL A thesis submitted to the Graduate College of Marshall University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Music Music History and Literature by Danielle Van Oort Approved by Dr. Vicki Stroeher, Committee Chairperson Dr. Ann Bingham Dr. Terry Dean, Indiana State University Marshall University May 2016 APPROVAL OF THESIS We, the faculty supervising the work of Danielle Van Oort, affirm that the thesis, Rest Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal, meets the high academic standards for original scholarship and creative work established by the School of Music and Theatre and the College of Arts and Media. This work also conforms to the editorial standards of our discipline and the Graduate College of Marshall University. With our signatures, we approve the manuscript for publication. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author would like to express appreciation and gratitude to the faculty and staff of Marshall University’s School of Music and Theatre for their continued support. -

INS Price 1F-$0.65 HC Not Available from EDRS. Basic Song List, While

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 048 320 T7 499 843 TITLE Music Appreciation for High School. Curriculum Bulletin, 1969-70 Series, No. 4. INSTITUTICN New York City Board of Education, Brooklyn, N.Y. Bureau of Curriculum Development. PUB DATE 69 NOTE 188p. AVAILABLE ERCM Eoard of Education of the City of Pew York, Publications Sales Office, 110 Livingston Street, Brooklyn, N.Y.11201 ($4.00). Make checks payable to Auuitor, Board of Education FURS PRICE INS Price 1F-$0.65 HC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS Bands (Music), Choral Music, Educational Objectives, *"tunic Activities, nisical Instruments, *Music Appreciatlon, *Music Education, Music Reading, Music Theory, Opera, Or-Jlestras, Oriental Music, Teaching Procedures, Vocal Music ABSTRACT Organized flexibly- these 17 unit. outlines are arranged to provide articulation with lower levels, utilization of student-preferred material, and coverage of the most essential instructional aspects of music appreciation in an increasing order of complexity. Each unit outline contains (1)aims and objectives, (2) vocabulary, (3) suggested and alternate lesson topics, (4) procedures,(F) summary concepts, (6) references, (7) audiovis.ial mat, al lists., (8) sample lesson plans, and (9) sample worksheets. The ,ntroducticn includes a sample pupil inventory lorm, an auditory discrimination test(of both performers and symphonic wor%s), and a basic song list, while suppleentary materials conclude the syllabus with lists of popular songs, au%iovisual aids, and recordings; an outline of musical rudimEnts; a sample lesson plan for appreciation and understanding of prograff music; and a bibliography. (JMC) OS DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH, EDUCATION a WAR! OFFICE OF EDUCATIO! !HIS DOCUMENT HIS ND REPRODUCED EXACTLY A: WEND IROM THE PERSON CR ORGANIZATtOH CR161111E10 ItPOINTS Of 011W OR OPINIONS STATED DO NOT KCESSIPILY REPREtrif OFFICIII OFFICE OF FIIKVION POSITION OR POOCH. -

Spotlight on Erie

From the Editors The local voice for news, Contents: March 2, 2016 arts, and culture. Different ways of being human Editors-in-Chief: Brian Graham & Adam Welsh Managing Editor: Erie At Large 4 We have held the peculiar notion that a person or Katie Chriest society that is a little different from us, whoever we Contributing Editors: The educational costs of children in pov- Ben Speggen erty are, is somehow strange or bizarre, to be distrusted or Jim Wertz loathed. Think of the negative connotations of words Contributors: like alien or outlandish. And yet the monuments and Lisa Austin, Civitas cultures of each of our civilizations merely represent Mary Birdsong Just a Thought 7 different ways of being human. An extraterrestrial Rick Filippi Gregory Greenleaf-Knepp The upside of riding downtown visitor, looking at the differences among human beings John Lindvay and their societies, would find those differences trivial Brianna Lyle Bob Protzman compared to the similarities. – Carl Sagan, Cosmos Dan Schank William G. Sesler Harrisburg Happenings 7 Tommy Shannon n a presidential election year, what separates us Ryan Smith Only unity can save us from the ominous gets far more airtime than what connects us. The Ti Summer storm cloud of inaction hanging over this neighbors you chatted amicably with over the Matt Swanseger I Sara Toth Commonwealth. drone of lawnmowers put out a yard sign supporting Bryan Toy the candidate you loathe, and suddenly they’re the en- Nick Warren Senator Sean Wiley emy. You’re tempted to un-friend folks with opposing Cover Photo and Design: The Cold Realities of a Warming World 8 allegiances right and left on Facebook. -

A Conductor's Study of George Rochberg's Three Psalm Settings David Lawrence Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Major Papers Graduate School 2002 A conductor's study of George Rochberg's three psalm settings David Lawrence Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_majorpapers Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Lawrence, David, "A conductor's study of George Rochberg's three psalm settings" (2002). LSU Major Papers. 51. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_majorpapers/51 This Major Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Major Papers by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A CONDUCTOR’S STUDY OF GEORGE ROCHBERG’S THREE PSALM SETTINGS A Monograph Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in School of Music By David Alan Lawrence B.M.E., Abilene Christian University, 1987 M.M., University of Washington, 1994 August 2002 ©Copyright 2002 David Alan Lawrence All rights reserved. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES ....................................................................................................................v LIST OF FIGURES..................................................................................................................vi LIST -

Ramones 2002.Pdf

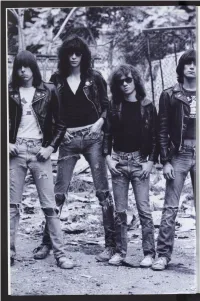

PERFORMERS THE RAMONES B y DR. DONNA GAINES IN THE DARK AGES THAT PRECEDED THE RAMONES, black leather motorcycle jackets and Keds (Ameri fans were shut out, reduced to the role of passive can-made sneakers only), the Ramones incited a spectator. In the early 1970s, boredom inherited the sneering cultural insurrection. In 1976 they re earth: The airwaves were ruled by crotchety old di corded their eponymous first album in seventeen nosaurs; rock & roll had become an alienated labor - days for 16,400. At a time when superstars were rock, detached from its roots. Gone were the sounds demanding upwards of half a million, the Ramones of youthful angst, exuberance, sexuality and misrule. democratized rock & ro|ft|you didn’t need a fat con The spirit of rock & roll was beaten back, the glorious tract, great looks, expensive clothes or the skills of legacy handed down to us in doo-wop, Chuck Berry, Clapton. You just had to follow Joey’s credo: “Do it the British Invasion and surf music lost. If you were from the heart and follow your instincts.” More than an average American kid hanging out in your room twenty-five years later - after the band officially playing guitar, hoping to start a band, how could you broke up - from Old Hanoi to East Berlin, kids in full possibly compete with elaborate guitar solos, expen Ramones regalia incorporate the commando spirit sive equipment and million-dollar stage shows? It all of DIY, do it yourself. seemed out of reach. And then, in 1974, a uniformed According to Joey, the chorus in “Blitzkrieg Bop” - militia burst forth from Forest Hills, Queens, firing a “Hey ho, let’s go” - was “the battle cry that sounded shot heard round the world. -

Teaching Post-Tonal Music to Twenty-First- Century Students Author(S): Miguel A

Department of Music Theory, Jacobs School of Music, Indiana University A Pedagogical and Psychological Challenge: Teaching Post-Tonal Music to Twenty-First- Century Students Author(s): Miguel A. Roig-Francolí Source: Indiana Theory Review, Vol. 33, No. 1-2 (Summer 2017), pp. 36-68 Published by: Indiana University Press on behalf of the Department of Music Theory, Jacobs School of Music, Indiana University Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2979/inditheorevi.33.1-2.02 Accessed: 03-09-2018 01:27 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms Indiana University Press, Department of Music Theory, Jacobs School of Music, Indiana University are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Indiana Theory Review This content downloaded from 129.74.250.206 on Mon, 03 Sep 2018 01:27:00 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms A Pedagogical and Psychological Challenge: Teaching Post-Tonal Music to Twenty-First-Century Students Miguel A. Roig-Francolí University of Cincinnati ost-tonal music has a pr problem among young musicians, and many not-so-young ones. Anyone who has recently taught a course on the theory and analysis of post-tonal music to a general Pmusic student population mostly made up of performers, be it at the undergraduate or master’s level, will probably immediately understand what the title of this article refers to. -

Waylon Jennings

TABLE OF CONTENTS 3 Introduction 4 About the Guide 5 Pre and Post-Lesson: Anticipation Guide 6 Lesson 1: Introduction to Outlaws 7 Lesson 1: Worksheet 8 Lyric Sheet: Me and Paul 9 Lesson 2: Who Were The Outlaws? 10 Lesson 3: Outlaw Influence 11 Lesson 3: Worksheet 12 Activities: Jigsaw Texts 14 Lyric Sheet: Are You Sure Hank Done It This Way 15 Lesson 4: T for Texas, T for Tennessee 16 Lesson 4: Worksheet 17 Lesson 5: Literary Lyrics 19 “London” by William Blake 20 Complete Tennessee Standards 22 Complete Texas Standards 23 Biographies 3-6 Table of Contents 2 Outlaws and Armadillos: Country’s Roaring ‘70s examines how the Outlaw movement greatly enlarged country music’s audience during the 1970s. Led by pacesetters such as Willie Nelson, Waylon Jennings, Kris Kristofferson, and Bobby Bare, artists in Nashville and Austin demanded the creative freedom to make their own country music, different from the pop-oriented sound that prevailed at the time. This exhibition also examines the cultures of Nashville and fiercely independent Austin, and the complicated, surprising relationships between the two. Artwork by Sam Yeates, Rising from the Ashes, Willie Takes Flight for Austin (2017) 3-6 Introduction 3 This interdisciplinary lesson guide allows classrooms to explore the exhibition Outlaws and Armadillos: Country’s Roaring ‘70s on view at the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum® from May 25, 2018 – February 14, 2021. Students will examine the causes and effects of the Outlaw movement through analysis of art, music, video, and nonfiction texts. In doing so, students will gain an understanding of the culture of this movement; who and what influenced it; and how these changes diversified country music’s audience during this time. -

The SAT. Question And-Answer Service

October 2020 The SAT. Question and-Answer Service Use this with your QAS Student Guide and personalized QAS Report. What's inside: The SAT and SAT Essay administered on your test day e CollegeBoard NOT FOR REPRODUCTION OR RESALE. Question-and-Answer11 Service Student Guide Reading Test 65 MINUTES, 52 QUESTIONS Turn to Section 1 of your answer sheet to answer the questions in this section. Each passage or pair of passages below is followed by a number of questions. After reading each passage or pair, choose the best answer to each question based on what is stated or implied in the passage or passages and in any accompanying graphics (such as a table or graph). ............................................................................................................................... Questions 1-10 are based on the following For a while I stayed there and tried to imagine passage. 30 what it was I actually knew. I'd seen almost nothing of This passage is adapted from Meg Wolitzer, The Wife. the world; a trip to Rome and Florence with my Originally published in 2003. The narrator, a student at parents when I was fifteen had been spent in the Smith College, a women's college, is enrolled in a creative protection of good hotels and pinned behind the writing class in the 1950s. green-glass windows of tour buses, looking at stone 35 fountains in piazzas from an unreal remove. The level "Write what you know," Professor Castleman of my experience and knowledge had remained the Line advised as he sent us off to complete the writing same, hadn't risen, hadn't overflowed. -

Proquest Dissertations

The use of the glissando in piano solo and concerto compositions from Domenico Scarlatti to George Crumb Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Lin, Shuennchin Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 30/09/2021 08:04:22 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/288715 INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI fihns the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter fice, whfle others may be from any type of computer primer. The qaality^ of this rqirodnctioii is dependent upon the quality of the copy sabmitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and hnproper alignmem can adverse^ affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., nu^s, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, b^inning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing fi'om left to right m equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. -

ISSUE 4 FALL 2000 CONTENTS DEFINING the WIND Defining the Wind Band Sound

A JOURNAL FOR THE CONTEMPORARY WIND BAND ISSUE 4 FALL 2000 CONTENTS DEFINING THE WIND Defining the Wind Band Sound ... page I BAND SOUND: by Donald Hunsberger Patrick Gi lmore and his contributions to the THE GILMORE ERA (1859-1892) development of the American wind band BY DONALD HUNSBERGER INSIGHTS Three Japanese Dances .. page 12 In Wine/Works Issue 2, we discussed the development and influence of the English militm)l by Bernard Rogers band journal in shaping English ensembles during the second half of the 19th centu1y. A new full score and set of pruts in an edition These English band practices were brought to America by music and instrument distributors by Timothy Topolewski and furth er highlighted by the visit of Daniel Godfrey and the Band of the Grenadier Guards CONVERSATIONS to Boston in 1872. The one person who, above others, may be credited for creating fonvard A Talk with Frederick Fennell .. page 18 movement in American band instrumentation is Patrick Gilmore, whose contributions were Conductor Fennell talks about hi s eru·ly previously listed as occurring through instrumentation expansion, balancing the number of impressions of the first performance of pe1jormers, and especially through his awakening both the A1nerican public and the musical the Three Japanese Dances in 1934 world to the vast untapped potential of the full woodwind-brass-percussion ensemble [WindWorks Issue 3]. A Talk with Mrs. Beman/ Rogers ... page 20 Elizabeth Rogers discusses Bernru·d Rogers' Th e period between the Civil War and John Philip Sousa ssuccess with his own professional approach to writing the Three Japanese Dances band in the 1890s has been somewhat of a historical "black hole" due to a lack of available resources; it is hoped that important events and developments may be fo llowed through WIND LIBRARY analysis of instrumentation/personnel changes and especially through actual scores of the Catfish Row by George Gershwin .. -

Emily Dickinson in Song

1 Emily Dickinson in Song A Discography, 1925-2019 Compiled by Georgiana Strickland 2 Copyright © 2019 by Georgiana W. Strickland All rights reserved 3 What would the Dower be Had I the Art to stun myself With Bolts of Melody! Emily Dickinson 4 Contents Preface 5 Introduction 7 I. Recordings with Vocal Works by a Single Composer 9 Alphabetical by composer II. Compilations: Recordings with Vocal Works by Multiple Composers 54 Alphabetical by record title III. Recordings with Non-Vocal Works 72 Alphabetical by composer or record title IV: Recordings with Works in Miscellaneous Formats 76 Alphabetical by composer or record title Sources 81 Acknowledgments 83 5 Preface The American poet Emily Dickinson (1830-1886), unknown in her lifetime, is today revered by poets and poetry lovers throughout the world, and her revolutionary poetic style has been widely influential. Yet her equally wide influence on the world of music was largely unrecognized until 1992, when the late Carlton Lowenberg published his groundbreaking study Musicians Wrestle Everywhere: Emily Dickinson and Music (Fallen Leaf Press), an examination of Dickinson's involvement in the music of her time, and a "detailed inventory" of 1,615 musical settings of her poems. The result is a survey of an important segment of twentieth-century music. In the years since Lowenberg's inventory appeared, the number of Dickinson settings is estimated to have more than doubled, and a large number of them have been performed and recorded. One critic has described Dickinson as "the darling of modern composers."1 The intriguing question of why this should be so has been answered in many ways by composers and others.