Emily Dickinson in Song

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How Democratic Is Jazz?

Accepted Manuscript Version Version of Record Published in Finding Democracy in Music, ed. Robert Adlington and Esteban Buch (New York: Routledge, 2021), 58–79 How Democratic Is Jazz? BENJAMIN GIVAN uring his 2016 election campaign and early months in office, U.S. President Donald J. Trump was occasionally compared to a jazz musician. 1 His Dnotorious tendency to act without forethought reminded some press commentators of the celebrated African American art form’s characteristic spontaneity.2 This was more than a little odd. Trump? Could this corrupt, capricious, megalomaniacal racist really be the Coltrane of contemporary American politics?3 True, the leader of the free world, if no jazz lover himself, fully appreciated music’s enormous global appeal,4 and had even been known in his youth to express his musical opinions in a manner redolent of great jazz musicians such as Charles Mingus and Miles Davis—with his fists. 5 But didn’t his reckless administration I owe many thanks to Robert Adlington, Ben Bierman, and Dana Gooley for their advice, and to the staffs of the National Museum of American History’s Smithsonian Archives Center and the New York Public Library’s Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. Copyright © 2020 by Benjamin Givan. 1 David Hajdu, “Trump the Improviser? This Candidate Operates in a Jazz-Like Fashion, But All He Makes is Unexpected Noise,” The Nation, January 21, 2016 (https://www.thenation.com/article/tr ump-the-improviser/ [accessed May 14, 2019]). 2 Lawrence Rosenthal, “Trump: The Roots of Improvisation,” Huffington Post, September 9, 2016 (https://www.huffpost.com/entry/trump-the-roots-of-improv_b_11739016 [accessed May 14, 2019]); Michael D. -

Fond Affection Music of Ernst Bacon

NWCR890 Fond Affection Music of Ernst Bacon Baritone Songs: Settings of poems by Walt Whitman (8-12); Carl Sandburg (13); Emily Dickinson (14-15); A.E. Housman (16); and Ernst Bacon (17). 8. The Commonplace ................................... (1:05) 9. Grand Is the Seen ..................................... (2:48) 10. Lingering Last Drops ............................... (1:57) 11. The Last Invocation .................................. (2:23) 12. The Divine Ship ....................................... (1:04) 13. Omaha ...................................................... (1:29) 14. It’s coming—the postponeless Creature ... (2:36) 15. How Still the bells .................................... (2:01) 16. Farewell to a name and a number ............. (1:28) 17. Brady ........................................................ (2:07) William Sharp, baritone; John Musto, piano Soprano Songs: Settings of poems by Emily Dickinson (18- 21); William Blake (22); 17th-century English text (23); Cho Wen-chun, tr. Arthur Waley (24); and Helena Carus (25) 18. It’s All I Have To Bring ........................... (1:16) 19. Velvet People ........................................... (1:37) 20. The Bat ..................................................... (1:56) 21. Wild Nights .............................................. (1:18) 22. The Lamb ................................................. (2:43) 23. Little Boy ................................................. (2:42) 24. Song of Snow-white Heads ...................... (2:35) 25. A Brighter Morning ................................. -

Tracing the Development of Extended Vocal Techniques in Twentieth-Century America

CRUMP, MELANIE AUSTIN. D.M.A. When Words Are Not Enough: Tracing the Development of Extended Vocal Techniques in Twentieth-Century America. (2008) Directed by Mr. David Holley, 93 pp. Although multiple books and articles expound upon the musical culture and progress of American classical, popular and folk music in the United States, there are no publications that investigate the development of extended vocal techniques (EVTs) throughout twentieth-century American music. Scholarly interest in the contemporary music scene of the United States abounds, but few sources provide information on the exploitation of the human voice for its unique sonic capabilities. This document seeks to establish links and connections between musical trends, major artistic movements, and the global politics that shaped Western art music, with those composers utilizing EVTs in the United States, for the purpose of generating a clearer musicological picture of EVTs as a practice of twentieth-century vocal music. As demonstrated in the connecting of musicological dots found in primary and secondary historical documents, composer and performer studies, and musical scores, the study explores the history of extended vocal techniques and the culture in which they flourished. WHEN WORDS ARE NOT ENOUGH: TRACING THE DEVELOPMENT OF EXTENDED VOCAL TECHNIQUES IN TWENTIETH-CENTURY AMERICA by Melanie Austin Crump A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate School at The University of North Carolina at Greensboro in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts Greensboro 2008 Approved by ___________________________________ Committee Chair To Dr. Robert Wells, Mr. Randall Outland and my husband, Scott Watson Crump ii APPROVAL PAGE This dissertation has been approved by the following committee of the Faculty of The School of Music at The University of North Carolina at Greensboro. -

ARSC Journal

LEONARD BERNSTEIN, A COMPOSER DISCOGRAPHY" Compiled by J. F. Weber Sonata for clarinet and piano (1941-42; first performed 4-21-42) David Oppenheim, Leonard Bernstein (recorded 1945) (78: Hargail set MW 501, 3ss.) Herbert Tichman, Ruth Budnevich (rec. c.1953} Concert Hall Limited Editions H 18 William Willett, James Staples (timing, 9:35) Mark MRS 32638 (released 12-70, Schwann) Stanley Drucker, Leonid Hambro (rec. 4-70) (10:54) Odyssey Y 30492 (rel. 5-71) (7) Anniversaries (for piano) (1942-43) (2,5,7) Leonard Bernstein (o.v.) (rec. 1945) (78: Hargail set MW 501, ls.) (1,2,3) Leonard Bernstein (rec. c.1949) (4:57) (78: RCA Victor 12 0683 in set DM 1278, ls.) Camden CAL 214 (rel. 5-55, del. 2-58) (4,5) Leonard Bernstein (rec. c.1949) (3:32) (78: RCA Victor 12 0228 in set DM 1209, ls.) (vinyl 78: RCA Victor 18 0114 in set DV 15, ls.) Camden CAL 214 (rel. 5-55, del. 2-58); CAL 351 (6,7) Leonard Bernstein (rec. c.1949) (2:18) Camden CAL 214 (rel. 5-55, del. 2-58); CAL 351 Jeremiah symphony (1941-44; f.p. 1-28-44) Nan Merriman, St. Louis SO--Leonard Bernstein (rec. 12-1-45) ( 23: 30) (78: RCA Victor 11 8971-3 in set DM 1026, 6ss.) Camden CAL 196 (rel. 2-55, del. 6-60) "Single songs from tpe Broadway shows and arrangements for band, piano, etc., are omitted. Thanks to Jane Friedmann, CBS; Peter Dellheim, RCA; Paul de Rueck, Amberson Productions; George Sponhaltz, Capitol; James Smart, Library of Congress; Richard Warren, Jr., Yael Historical Sound Recordings; Derek Lewis, BBC. -

Jazz Faculty and Friends

Kennesaw State University Upcoming Music Events Thursday-Sunday, November 5-8 Kennesaw State University Opera Theatre Dean Joseph D. Meeks The Medium dean The Stoned Guest Howard Logan Stillwell Theatre School of Music Tuesday, November 10 Kennesaw State University presents Student Mixed Chamber Ensembles 8:00 pm • Bailey Performance Center Performance Hall Wednesday, November 11 Kennesaw State University Jazz Combos Kennesaw State University 8:00 pm • Bailey Performance Center Performance Hall Jazz Faculty and Friends Thursday, November 12 Kennesaw State University Jazz Ensembles 8:00 pm • Bailey Performance Center Performance Hall Sam Skelton, woodwinds Trey Wright, guitar Tuesday, November 17 Wes Funderburk, trombone Kennesaw State University Tyrone Jackson, piano Women’s Choral Day concert 7:30 pm • Bailey Performance Center Performance Hall Marc Miller, bass Justin Varnes, drums Wednesday, November 18 Kennesaw State University Jazz Guitar Ensemble 8:00 pm • Bailey Performance Center Performance Hall Wednesday, November 4, 2009 For the most current information, please visit http://www.kennesaw.edu/arts/events/ 8:00 pm Dr. Bobbie Bailey & Family Performance Center We welcome all guests with special needs and offer the following services: accessible seating, easy access, companion restroom locations, assisted listening devices. Please contact an audience services representative to request services Twentieth Concert of the 2009-2010 season Kennesaw State University (Harry Connick, Jr.), Aaron Goldberg (Joshua Redman), Wessell Anderson, School of Music Wycliffe Gordon, Marcus Printup, Steve Kirby (Cyrus Chestnut), Peter Bernstein, and Eric Lewis (Wynton Marsalis). Performance Hall Currently residing in Atlanta, Mr. Varnes performs regularly with the Christian Tamburr Quartet, as well as Bob Reynolds, Kevin Bales, Joe Gransden and Gary Motley. -

TONI PASSMORE ANDERSON 209 Lincoln Lane Lagrange, GA 30240 (706) 880-8264 [email protected]

TONI PASSMORE ANDERSON 209 Lincoln Lane LaGrange, GA 30240 (706) 880-8264 [email protected] EDUCATION: Georgia State University, Atlanta, Georgia Ph.D. in Higher Education, 1997 Dissertation Title: “The Fisk Jubilee Singers: Performing Ambassadors for the Survival of an American Treasure, 1871-1878" Courses in Music: Aesthetics of Music, Music Technology, Multicultural Music Education, Reference Materials and Research Methodology in Music New England Conservatory of Music, Boston, Massachusetts M.M. in Vocal Performance, May 1982 Voice with Susan Fisher Clickner; Opera with John Moriarty Lamar University, Beaumont, Texas B.M. in Music Education, May 1979 K-12 Certificate in State of Texas Other: Voice study with Susan Fisher Clickner, Irene Harrower, and Herald Stark; Coaching with Terry Decima, Maestro Rudolf Fellner, John Moriarty, James Gardner, Boris Goldovsky, Douglas Hines, John Douglas, Walter Huff. Vocal Master Classes with Eleanor Steber, Janice Harsanyi, Beverly Wolff. Four years of dance training (ballet, folk, movement for singers, jazz); eight years of private piano study. TEACHING AND ADMINISTRATIVE EXPERIENCE: LaGrange College, LaGrange, Georgia Fall 1999 - Present, Tenured Professor Chair, Music Program Co-Chair, Musical Theatre Program Musical Director/Conductor Courses Taught: Applied Voice; Diction for Singers; Opera Experience; Opera Survey; Music Survey; Interim Term travel experiences Morris Brown College, Atlanta, Georgia 1985-1999, Assistant Professor of Music Program Coordinator/Chair 1991; 1993-96 Tenured -

The George-Anne Student Media

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern The George-Anne Student Media 5-20-1966 The George-Anne Georgia Southern University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/george-anne Part of the Higher Education Commons Recommended Citation Georgia Southern University, "The George-Anne" (1966). The George-Anne. 471. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/george-anne/471 This newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Media at Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in The George-Anne by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ^^H pg^g^gg^fl^HHI See SOUTHERN THE BELLE CONTEST George -Anne Page 9 PUBLISHED BY STUDENTS OF GEORGIA SOUTHERN COLLEGE VOLUME 43 STATESBORO, GEORGIA, FRIDAY' MAY 20, 1966 NUMBER 9 One-Act Plays Set for Tuesday olff To Appear in Concert In Auditorium Campus Enrichment Committee A series of four one-act plays will be presented Tuesday night at 8:15 in McCroan Auditorium To Sponsor Monday Attraction by Robert Overstreet's direct- Miss Beverly Wolff, the final 1965-66 attraction of the Campus ing class. Masquers will spons- Life Enrichment Committee, will appear in concert Monday at or the series. 8:15 p.m. in McCroan Auditorium. The four directors are Lib- Her career as a New York church singing, sales clerking by Brannon, Ralph Jones, City Opera vocalist began in and baby sitting. Pam Theus and Parker Cook. 1963 when she sang the role The one-act play is presented of Cherubino in Mozart's Following her 1952 first place in partial fulfillment for the "Marriage of Figaro." This in the Youth Auditions of the completion of the directing debut was the result of a Philadelphia Orchestra she course. -

Smith College Alumnae Chorus to Honor Composer Alice Parker, Class of 1947, in Special Concert

Published on GazetteNet (http://www.gazettenet.com) Print this Page A lifetime of music; Smith College Alumnae Chorus to honor composer Alice Parker, class of 1947, in special concert By STEVE PFARRER Staff Writer Wednesday, September 17, 2014 (Published in print: Thursday, September 18, 2014) Who says your time singing in college has to end with graduation? For members of the Smith College Alumnae Chorus, launched four years ago, choral music remains a means for forging connections among graduates of different classes and keeping their voices raised in song. For Alice Parker, Smith class of 1947, choral music has been a lifelong calling — as a composer, a conductor and teacher. Parker, 88, has composed for decades, earning particular notice for her arrangements of folk songs and hymns for vocal ensembles. She collaborated for years on such material with the late Robert Shaw, known as “the Dean of American Choral Conductors.” On Sunday, Sept. 21, Parker and the Alumnae Chorus (SCAC) will join forces at Smith to celebrate Parker’s lifetime achievements in a 2 p.m. show at Sweeney Concert Hall. Part of the performance, which will be conducted by Parker, has a special connection to the Valley as well: Parker will lead the chorus in a rendition of her song cycle “Three Seas,” a suite based on the poetry of Emily Dickinson. Members of the SCAS, most of whom performed with one of more vocals groups at Smith when they were students, say the opportunity to work with Parker is an exciting one. “It’s really an honor,” Sarah Muffly, class of 2008 and the chorus’ secretary, said in a recent phone call from her home in the New York area. -

Click to Download

v8n4 covers.qxd 5/13/03 1:58 PM Page c1 Volume 8, Number 4 Original Music Soundtracks for Movies & Television Action Back In Bond!? pg. 18 MeetTHE Folks GUFFMAN Arrives! WIND Howls! SPINAL’s Tapped! Names Dropped! PLUS The Blue Planet GEORGE FENTON Babes & Brits ED SHEARMUR Celebrity Studded Interviews! The Way It Was Harry Shearer, Michael McKean, MARVIN HAMLISCH Annette O’Toole, Christopher Guest, Eugene Levy, Parker Posey, David L. Lander, Bob Balaban, Rob Reiner, JaneJane Lynch,Lynch, JohnJohn MichaelMichael Higgins,Higgins, 04> Catherine O’Hara, Martin Short, Steve Martin, Tom Hanks, Barbra Streisand, Diane Keaton, Anthony Newley, Woody Allen, Robert Redford, Jamie Lee Curtis, 7225274 93704 Tony Curtis, Janet Leigh, Wolfman Jack, $4.95 U.S. • $5.95 Canada JoeJoe DiMaggio,DiMaggio, OliverOliver North,North, Fawn Hall, Nick Nolte, Nastassja Kinski all mentioned inside! v8n4 covers.qxd 5/13/03 1:58 PM Page c2 On August 19th, all of Hollywood will be reading music. spotting editing composing orchestration contracting dubbing sync licensing music marketing publishing re-scoring prepping clearance music supervising musicians recording studios Summer Film & TV Music Special Issue. August 19, 2003 Music adds emotional resonance to moving pictures. And music creation is a vital part of Hollywood’s economy. Our Summer Film & TV Music Issue is the definitive guide to the music of movies and TV. It’s part 3 of our 4 part series, featuring “Who Scores Primetime,” “Calling Emmy,” upcoming fall films by distributor, director, music credits and much more. It’s the place to advertise your talent, product or service to the people who create the moving pictures. -

Edition 2 | 2018-2019

Terra Nova San Antonio 6983 Blanco Rd San Antonio, TX 78216 Ph: 210-349-4700 Fax: 210-349-4725 Terra Nova Austin 7795 Burnet Rd Austin, TX 78757 Ph: 512-640-4072 Fax: 512-879-6853 www.TerraNovaViolins.com Did You Know? Young people who participate in the arts for at least three hours on three days each week through at least one full year are: • 4 times more likely to be recognized for academic achievement • 3 times more likely to be elected to class office within their schools • 4 times more likely to participate in a math and science fair • 3 times more likely to win an award for school attendance • 4 times more likely to win an award for writing an essay or poem 2 AustinChamberMusic.org / 512.454.0026 AustinChamberMusic.org / 512.454.0026 3 Welcome to the 2018-2019 Concert Season: Landscapes 4 AustinChamberMusic.org / 512.454.0026 PERFORMANCES FRIDAY INTIMATE SEASON CONCERTS An up-close and personal setting for chamber music About ACMC in stylish Austin homes with post-concert reception. SATURDAY SYNCHRONISM SEASON CONCERTS MISSION Chamber music in public venues in tandem with The Austin Chamber Music Center (ACMC) is Intimate Concert performances. dedicated to serving Central Texans by expanding A CHARLIE BROWN CHRISTMAS knowledge, understanding, and appreciation of An annual holiday concert featuring all of your favorite chamber music through the highest quality instruction tunes from the TV classic. and performance. AUSTIN CHAMBER MUSIC FESTIVAL Featuring over 30 performances by internationally EDUCATION acclaimed local and visiting artists over three weeks. OPPORTUNITIES for musicians of all ages and A MOVEABLE FEAST CONCERT SERIES skill levels, including a Chamber Academy and A bi-annual series of adventurous programming ChamberFlex in the academic year, and an combining diverse music, visual art, cuisine, and a intensive Summer Workshop. -

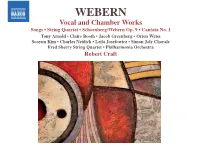

ANTON WEBERN Vol

WEBERN Vocal and Chamber Works Songs • String Quartet • Schoenberg/Webern Op. 9 • Cantata No. 1 Tony Arnold • Claire Booth • Jacob Greenberg • Orion Weiss Sooyun Kim • Charles Neidich • Leila Josefowicz • Simon Joly Chorale Fred Sherry String Quartet • Philharmonia Orchestra Robert Craft THE ROBERT CRAFT COLLECTION Four Songs for Voice and Piano, Op. 12 (1915-17) 5:28 THE MUSIC OF ANTON WEBERN Vol. 3 & I. Der Tag ist vergangen (Day is gone) Text: Folk-song 1:32 Recordings supervised by Robert Craft * II. Die Geheimnisvolle Flöte (The Mysterious Flute) Text by Li T’ai-Po (c.700-762), from Hans Bethge’s ‘Chinese Flute’ 1:32 Five Songs from Der siebente Ring (The Seventh Ring), Op. 3 (1908-09) 5:35 ( III. Schien mir’s, als ich sah die Sonne (It seemed to me, as I saw the sun) Texts by Stefan George (1868-1933) Text from ‘Ghost Sonata’ by August Strindberg (1849-1912) 1:32 1 I. Dies ist ein Lied für dich allein (This is a song for you alone) 1:19 ) IV. Gleich und gleich (Like and Like) 2 II. Im Windesweben (In the weaving of the wind) 0:36 Text by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749-1832) 0:52 3 III. An Bachesranft (On the brook’s edge) 1:00 Tony Arnold, Soprano • Jacob Greenberg, Piano 4 IV. Im Morgentaun (In the morning dew) 1:04 5 V. Kahl reckt der Baum (Bare stretches the tree) 1:36 Recorded at the American Academy of Arts and Letters, New York, on 28th September, 2011 Producer: Philip Traugott • Engineer: Tim Martyn • Editor: Jacob Greenberg • Assistant engineer: Brian Losch Tony Arnold, Soprano • Jacob Greenberg, Piano Recorded at the American Academy of Arts and Letters, New York, on 28th September, 2011 Three Songs from Viae inviae, Op. -

The Inventory of the Phyllis Curtin Collection #1247

The Inventory of the Phyllis Curtin Collection #1247 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center Phyllis Curtin - Box 1 Folder# Title: Photographs Folder# F3 Clothes by Worth of Paris (1900) Brooklyn Academy F3 F4 P.C. recording F4 F7 P. C. concert version Rosenkavalier Philadelphia F7 FS P.C. with Russell Stanger· FS F9 P.C. with Robert Shaw F9 FIO P.C. with Ned Rorem Fl0 F11 P.C. with Gerald Moore Fl I F12 P.C. with Andre Kostelanetz (Promenade Concerts) F12 F13 P.C. with Carlylse Floyd F13 F14 P.C. with Family (photo of Cooke photographing Phyllis) FI4 FIS P.C. with Ryan Edwards (Pianist) FIS F16 P.C. with Aaron Copland (televised from P.C. 's home - Dickinson Songs) F16 F17 P.C. with Leonard Bernstein Fl 7 F18 Concert rehearsals Fl8 FIS - Gunther Schuller Fl 8 FIS -Leontyne Price in Vienna FIS F18 -others F18 F19 P.C. with hairdresser Nina Lawson (good backstage photo) FI9 F20 P.C. with Darius Milhaud F20 F21 P.C. with Composers & Conductors F21 F21 -Eugene Ormandy F21 F21 -Benjamin Britten - Premiere War Requiem F2I F22 P.C. at White House (Fords) F22 F23 P.C. teaching (Yale) F23 F25 P.C. in Tel Aviv and U.N. F25 F26 P. C. teaching (Tanglewood) F26 F27 P. C. in Sydney, Australia - Construction of Opera House F27 F2S P.C. in Ipswich in Rehearsal (Castle Hill?) F2S F28 -P.C. in Hamburg (large photo) F2S F30 P.C. in Hamburg (Strauss I00th anniversary) F30 F31 P. C. in Munich - German TV F31 F32 P.C.