How Democratic Is Jazz?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

December 1992

VOLUME 16, NUMBER 12 MASTERS OF THE FEATURES FREE UNIVERSE NICKO Avant-garde drummers Ed Blackwell, Rashied Ali, Andrew JEFF PORCARO: McBRAIN Cyrille, and Milford Graves have secured a place in music history A SPECIAL TRIBUTE Iron Maiden's Nicko McBrain may by stretching the accepted role of When so respected and admired be cited as an early influence by drums and rhythm. Yet amongst a player as Jeff Porcaro passes metal drummers all over, but that the chaos, there's always been away prematurely, the doesn't mean he isn't as vital a play- great discipline and thought. music—and our lives—are never er as ever. In this exclusive interview, Learn how these free the same. In this tribute, friends find out how Nicko's drumming masters and admirers share their fond gears move, and what's tore down the walls. memories of Jeff, and up with Maiden's power- • by Bill Milkowski 32 remind us of his deep ful new album and tour. 28 contributions to our • by Teri Saccone art. 22 • by Robyn Flans THE PERCUSSIVE ARTS SOCIETY For thirty years the Percussive Arts Society has fostered credibility, exposure, and the exchange of ideas for percus- sionists of every stripe. In this special report, learn where the PAS has been, where it is, and where it's going. • by Rick Mattingly 36 MD TRIVIA CONTEST Win a Sonor Force 1000 drumkit—plus other great Sonor prizes! 68 COVER PHOTO BY MICHAEL BLOOM Education 58 ROCK 'N' JAZZ CLINIC Back To The Dregs BY ROD MORGENSTEIN Equipment Departments 66 BASICS 42 PRODUCT The Teacher Fallacy News BY FRANK MAY CLOSE-UP 4 EDITOR'S New Sabian Products OVERVIEW BY RICK VAN HORN, 8 UPDATE 68 CONCEPTS ADAM BUDOFSKY, AND RICK MATTINGLY Tommy Campbell, Footwork: 6 READERS' Joel Maitoza of 24-7 Spyz, A Balancing Act 45 Yamaha Snare Drums Gary Husband, and the BY ANDREW BY RICK MATTINGLY PLATFORM Moody Blues' Gordon KOLLMORGEN Marshall, plus News 47 Cappella 12 ASK A PRO 90 TEACHERS' Celebrity Sticks BY ADAM BUDOFSKY 146 INDUSTRY FORUM AND WILLIAM F. -

UT Jazz Jury Repertoire – 5/2/06 Afternoon in Paris 43 a Foggy Day

UT Jazz Jury Repertoire – 5/2/06 Level 1 Tunes JA Level 2 Tunes JA Level 3 Tunes JA Level 4 Tunes JA Afternoon in Paris 43 A Foggy Day 25 Alone Together 41 Airegin 8 All Blues 50 A Night in Tunisia 43 Anthropology (Thrivin’ from a Riff) 6 Along Came Betty 14 A Time for Love 40 Afro Blue 64 Blue in Green 50 Beyond All Limits 9 Autumn Leaves 54 All the Things You Are 43 Body and Soul 41 Blood Count 66 Blue Bossa 54 Angel Eyes 23 Ceora 106 Bolivia 35 But Beautiful 23 Bird Blues (Blues 4 Alice) 2 Chelsea Bridge 66 Brite Piece 19 C Jam Blues 48 Bluesette 43 Children of the Night 33 Cherokee 15 Cantaloupe Island (96) 54 But Not for Me 65 Come Rain or Come Shine 25 Clockwise 35 Cantaloupe Island (132) 11 Cottontail 48 Confirmation 6 Countdown 28 Days of Wine and Roses 40 Don’t Get Around Much Anymore48 Corcovado-Quiet Nights 98 Dolphin Dance 11 Doxy (134) 54 Easy Living 52 Desafinado (184) 74 E.S.P. 33 Doxy (92) 8 Everything Happens to Me 23 Desafinado (136) 98 Giant Steps 28 Freddie the Freeloader 50 Footprints 33 Donna Lee 6 I'll Remember April 43 For Heaven’s Sake 89 Four 7 Embraceable You 51 Infant Eyes 33 Georgia 49 Groovin’ High 43 Estate 94 Inner Urge 108 Honeysuckle Rose 71 Have You Met Miss Jones 25 Fee Fi Fo Fum 33 It’s You or No One 61 I Got It Bad 48 Here’s That Rainy Day 23 Goodbye 94 Joshua 50 Impressions (112) 54 How Insensitive 98 I Can’t Get Started 25 Katrina Ballerina 9 Impressions (224) 28 I Didn’t Know About You 48 I Mean You 56 Lament for Booker 60 Killer Joe 70 I Hear a Rhapsody 80 In Case You Haven’t Heard 9 Love for -

Vindicating Karma: Jazz and the Black Arts Movement

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-2007 Vindicating karma: jazz and the Black Arts movement/ W. S. Tkweme University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Tkweme, W. S., "Vindicating karma: jazz and the Black Arts movement/" (2007). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 924. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/924 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. University of Massachusetts Amherst Library Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2014 https://archive.org/details/vindicatingkarmaOOtkwe This is an authorized facsimile, made from the microfilm master copy of the original dissertation or master thesis published by UMI. The bibliographic information for this thesis is contained in UMTs Dissertation Abstracts database, the only central source for accessing almost every doctoral dissertation accepted in North America since 1861. Dissertation UMI Services From:Pro£vuest COMPANY 300 North Zeeb Road P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106-1346 USA 800.521.0600 734.761.4700 web www.il.proquest.com Printed in 2007 by digital xerographic process on acid-free paper V INDICATING KARMA: JAZZ AND THE BLACK ARTS MOVEMENT A Dissertation Presented by W.S. TKWEME Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 W.E.B. -

Selected Observations from the Harlem Jazz Scene By

SELECTED OBSERVATIONS FROM THE HARLEM JAZZ SCENE BY JONAH JONATHAN A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-Newark Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Graduate Program in Jazz History and Research Written under the direction of Dr. Lewis Porter and approved by ______________________ ______________________ Newark, NJ May 2015 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements Page 3 Abstract Page 4 Preface Page 5 Chapter 1. A Brief History and Overview of Jazz in Harlem Page 6 Chapter 2. The Harlem Race Riots of 1935 and 1943 and their relationship to Jazz Page 11 Chapter 3. The Harlem Scene with Radam Schwartz Page 30 Chapter 4. Alex Layne's Life as a Harlem Jazz Musician Page 34 Chapter 5. Some Music from Harlem, 1941 Page 50 Chapter 6. The Decline of Jazz in Harlem Page 54 Appendix A historic list of Harlem night clubs Page 56 Works Cited Page 89 Bibliography Page 91 Discography Page 98 3 Acknowledgements This thesis is dedicated to all of my teachers and mentors throughout my life who helped me learn and grow in the world of jazz and jazz history. I'd like to thank these special people from before my enrollment at Rutgers: Andy Jaffe, Dave Demsey, Mulgrew Miller, Ron Carter, and Phil Schaap. I am grateful to Alex Layne and Radam Schwartz for their friendship and their willingness to share their interviews in this thesis. I would like to thank my family and loved ones including Victoria Holmberg, my son Lucas Jonathan, my parents Darius Jonathan and Carrie Bail, and my sisters Geneva Jonathan and Orelia Jonathan. -

Jazz Faculty and Friends

Kennesaw State University Upcoming Music Events Thursday-Sunday, November 5-8 Kennesaw State University Opera Theatre Dean Joseph D. Meeks The Medium dean The Stoned Guest Howard Logan Stillwell Theatre School of Music Tuesday, November 10 Kennesaw State University presents Student Mixed Chamber Ensembles 8:00 pm • Bailey Performance Center Performance Hall Wednesday, November 11 Kennesaw State University Jazz Combos Kennesaw State University 8:00 pm • Bailey Performance Center Performance Hall Jazz Faculty and Friends Thursday, November 12 Kennesaw State University Jazz Ensembles 8:00 pm • Bailey Performance Center Performance Hall Sam Skelton, woodwinds Trey Wright, guitar Tuesday, November 17 Wes Funderburk, trombone Kennesaw State University Tyrone Jackson, piano Women’s Choral Day concert 7:30 pm • Bailey Performance Center Performance Hall Marc Miller, bass Justin Varnes, drums Wednesday, November 18 Kennesaw State University Jazz Guitar Ensemble 8:00 pm • Bailey Performance Center Performance Hall Wednesday, November 4, 2009 For the most current information, please visit http://www.kennesaw.edu/arts/events/ 8:00 pm Dr. Bobbie Bailey & Family Performance Center We welcome all guests with special needs and offer the following services: accessible seating, easy access, companion restroom locations, assisted listening devices. Please contact an audience services representative to request services Twentieth Concert of the 2009-2010 season Kennesaw State University (Harry Connick, Jr.), Aaron Goldberg (Joshua Redman), Wessell Anderson, School of Music Wycliffe Gordon, Marcus Printup, Steve Kirby (Cyrus Chestnut), Peter Bernstein, and Eric Lewis (Wynton Marsalis). Performance Hall Currently residing in Atlanta, Mr. Varnes performs regularly with the Christian Tamburr Quartet, as well as Bob Reynolds, Kevin Bales, Joe Gransden and Gary Motley. -

The Problem with Borat

Taboo: The Journal of Culture and Education Volume 11 | Issue 1 Article 9 December 2007 The rP oblem with Borat Ghada Chehade Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/taboo Recommended Citation Chehade, G. (2017). The rP oblem with Borat. Taboo: The Journal of Culture and Education, 11 (1). https://doi.org/10.31390/ taboo.11.1.09 Taboo, Spring-Summer-Fall-WinterGhada Chehade 2007 63 The Problem with Borat Ghada Chehade There is just something about Borat, Sacha Baron Cohen’s barbaric alter-ego who The Observer’s Oliver Marre (2006) aptly describes as “…homophobic, rac- ist, and misogynist as well as anti-Semitic.” While on the surface, Cohen’s Borat may seem to offend all races equally—the one group he offends the most is the very group he portrays as homophobic, racist, misogynist, and anti-Semitic. Or in other words, the real parties vilified by Cohen are not Borat’s victims but Borat himself. The humour is ultimately directed at this uncivilized buffoon-Borat. He is the butt of every joke. He is the one we laugh at, and are intended to laugh at, the most inasmuch as he is more vulgar, savage, ignorant, barbaric, and racist than any of the bigoted Americans “exposed” in the 2006 film Borat: Cultural Learn- ings of America for Make Benefit Glorious Nation of Kazakhstan. This would not be quite as problematic if the fictional Borat did not come from a very real place and did not so obviously (mis)represent Muslims. While the 2006 film has received coverage and praise for revealing the racism of Americans, very few people are asking whether Cohen’s caricature of a savage, homophobic, misogynist, racist, and hard core Jew-hating Muslim is not actually a form of anti-Muslim racism. -

Shadows in the Field Second Edition This Page Intentionally Left Blank Shadows in the Field

Shadows in the Field Second Edition This page intentionally left blank Shadows in the Field New Perspectives for Fieldwork in Ethnomusicology Second Edition Edited by Gregory Barz & Timothy J. Cooley 1 2008 1 Oxford University Press, Inc., publishes works that further Oxford University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education. Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Copyright # 2008 by Oxford University Press Published by Oxford University Press, Inc. 198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016 www.oup.com Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Shadows in the field : new perspectives for fieldwork in ethnomusicology / edited by Gregory Barz & Timothy J. Cooley. — 2nd ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-19-532495-2; 978-0-19-532496-9 (pbk.) 1. Ethnomusicology—Fieldwork. I. Barz, Gregory F., 1960– II. Cooley, Timothy J., 1962– ML3799.S5 2008 780.89—dc22 2008023530 135798642 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper bruno nettl Foreword Fieldworker’s Progress Shadows in the Field, in its first edition a varied collection of interesting, insightful essays about fieldwork, has now been significantly expanded and revised, becoming the first comprehensive book about fieldwork in ethnomusicology. -

(You Gotta) Fight for Your Right (To Party!) 3 AM ± Matchbox Twenty. 99 Red Ballons ± Nena

(You Gotta) Fight For Your Right (To Party!) 3 AM ± Matchbox Twenty. 99 Red Ballons ± Nena. Against All Odds ± Phil Collins. Alive and kicking- Simple minds. Almost ± Bowling for soup. Alright ± Supergrass. Always ± Bon Jovi. Ampersand ± Amanda palmer. Angel ± Aerosmith Angel ± Shaggy Asleep ± The Smiths. Bell of Belfast City ± Kristy MacColl. Bitch ± Meredith Brooks. Blue Suede Shoes ± Elvis Presely. Bohemian Rhapsody ± Queen. Born In The USA ± Bruce Springstein. Born to Run ± Bruce Springsteen. Boys Will Be Boys ± The Ordinary Boys. Breath Me ± Sia Brown Eyed Girl ± Van Morrison. Brown Eyes ± Lady Gaga. Chasing Cars ± snow patrol. Chasing pavements ± Adele. Choices ± The Hoosiers. Come on Eileen ± Dexy¶s midnight runners. Crazy ± Aerosmith Crazy ± Gnarles Barkley. Creep ± Radiohead. Cupid ± Sam Cooke. Don¶t Stand So Close to Me ± The Police. Don¶t Speak ± No Doubt. Dr Jones ± Aqua. Dragula ± Rob Zombie. Dreaming of You ± The Coral. Dreams ± The Cranberries. Ever Fallen In Love? ± Buzzcocks Everybody Hurts ± R.E.M. Everybody¶s Fool ± Evanescence. Everywhere I go ± Hollywood undead. Evolution ± Korn. FACK ± Eminem. Faith ± George Micheal. Feathers ± Coheed And Cambria. Firefly ± Breaking Benjamin. Fix Up, Look Sharp ± Dizzie Rascal. Flux ± Bloc Party. Fuck Forever ± Babyshambles. Get on Up ± James Brown. Girl Anachronism ± The Dresden Dolls. Girl You¶ll Be a Woman Soon ± Urge Overkill Go Your Own Way ± Fleetwood Mac. Golden Skans ± Klaxons. Grounds For Divorce ± Elbow. Happy ending ± MIKA. Heartbeats ± Jose Gonzalez. Heartbreak Hotel ± Elvis Presely. Hollywood ± Marina and the diamonds. I don¶t love you ± My Chemical Romance. I Fought The Law ± The Clash. I Got Love ± The King Blues. I miss you ± Blink 182. -

John Cage's Entanglement with the Ideas Of

JOHN CAGE’S ENTANGLEMENT WITH THE IDEAS OF COOMARASWAMY Edward James Crooks PhD University of York Music July 2011 John Cage’s Entanglement with the Ideas of Coomaraswamy by Edward Crooks Abstract The American composer John Cage was famous for the expansiveness of his thought. In particular, his borrowings from ‘Oriental philosophy’ have directed the critical and popular reception of his works. But what is the reality of such claims? In the twenty years since his death, Cage scholars have started to discover the significant gap between Cage’s presentation of theories he claimed he borrowed from India, China, and Japan, and the presentation of the same theories in the sources he referenced. The present study delves into the circumstances and contexts of Cage’s Asian influences, specifically as related to Cage’s borrowings from the British-Ceylonese art historian and metaphysician Ananda K. Coomaraswamy. In addition, Cage’s friendship with the Jungian mythologist Joseph Campbell is detailed, as are Cage’s borrowings from the theories of Jung. Particular attention is paid to the conservative ideology integral to the theories of all three thinkers. After a new analysis of the life and work of Coomaraswamy, the investigation focuses on the metaphysics of Coomaraswamy’s philosophy of art. The phrase ‘art is the imitation of nature in her manner of operation’ opens the doors to a wide- ranging exploration of the mimesis of intelligible and sensible forms. Comparing Coomaraswamy’s ‘Traditional’ idealism to Cage’s radical epistemological realism demonstrates the extent of the lack of congruity between the two thinkers. In a second chapter on Coomaraswamy, the extent of the differences between Cage and Coomaraswamy are revealed through investigating their differing approaches to rasa , the Renaissance, tradition, ‘art and life’, and museums. -

Days and Nights Waiting Keith Jarrett on the Trail Ferde Grofe/Oscar

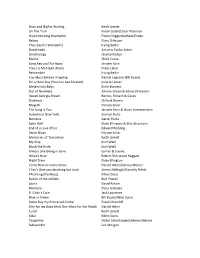

Days and Nights Waiting Keith Jarrett On The Trail Ferde Grofe/Oscar Peterson Good Morning Heartache Fisher/Higgenbotham/Drake Bebop Dizzy Gillespie They Say It's Wonderful Irving Berlin Desafinado Antonio Carlos Jobim Ornithology Charlie Parker Matrix Chick Corea Long Ago and Far Away Jerome Kern Yours is My Heart Alone Franz Lehar Remember Irving Berlin You Must Believe in Spring Michel Legrand (Bill Evans) On a Clear Day (You Can See Forever) Lane & Lerner Melancholy Baby Ernie Burnett Out of Nowhere Johnny Green & Edward Heyman Sweet Georgia Brown Bernie, Finkard & Casey Daahoud Clifford Brown Mayreh Horace Silver The Song is You Jerome Kern & Oscar Hammerstein Autumn in New York Vernon Duke Nemesis Aaron Parks Satin Doll Duke Ellington & Billy Strayhorn End of a Love Affair Edward Redding Senor Blues Horace Silver Memories of Tomorrow Keith Jarrett My Ship Kurt Weill Mack the Knife Kurt Weill Almost Like Being in Love Lerner & Loewe What's New Robert Sherwood Haggart Night Train Duke Ellington Come Rain or Come Shine Harold Arlen/Johnny Mercer I Can't Give you Anything but Love Jimmy McHugh/Dorothy Fields Pfrancing (No Blues) Miles Davis Dance of the Infidels Bud Powell Laura David Raksin Manteca Dizzy Gillespie If I Didn't Care Jack Lawrence Blue in Green Bill Evans/Miles Davis Some Day my Prince will Come Frank Churchill One for my Baby (And One More for the Road) Harold Arlen Coral Keith Jarrett Solar Miles Davis Tangerine Victor Schertzinger/Johnny Mercer Sidewinder Lee Morgan Dexterity Charlie Parker Cantaloupe Island Herbie -

Has TV Eaten Itself? RTS STUDENT TELEVISION AWARDS 2014 5 JUNE 1:00Pm BFI Southbank, London SE1 8XT

May 2015 Has TV eaten itself? RTS STUDENT TELEVISION AWARDS 2014 5 JUNE 1:00pm BFI Southbank, London SE1 8XT Hosted by Romesh Ranganathan. Nominated films and highlights of the awards ceremony will be broadcast by Sky www.rts.org.uk Journal of The Royal Television Society May 2015 l Volume 52/5 From the CEO The general election are 16-18 September. I am very proud I’d like to thank everyone who has dominated the to say that we have assembled a made the recent, sold-out RTS Futures national news agenda world-class line-up of speakers. evening, “I made it in… digital”, such a for much of the year. They include: Michael Lombardo, success. A full report starts on page 23. This month, the RTS President of Programming at HBO; Are you a fan of Episodes, Googlebox hosts a debate in Sharon White, CEO of Ofcom; David or W1A? Well, who isn’t? This month’s which two of televi- Abraham, CEO at Channel 4; Viacom cover story by Stefan Stern takes a sion’s most experienced anchor men President and CEO Philippe Dauman; perceptive look at how television give an insider’s view of what really Josh Sapan, President and CEO of can’t stop making TV about TV. It’s happened in the political arena. AMC Networks; and David Zaslav, a must-read. Jeremy Paxman and Alastair Stew- President and CEO of Discovery So, too, is Richard Sambrook’s TV art are in conversation with Steve Communications. Diary, which provides some incisive Hewlett at a not-to-be missed Leg- Next month sees the 20th RTS and timely analysis of the election ends’ Lunch on 19 May. -

Viktoria Tolstoy

Viktoria Tolstoy Letters to Herbie ACT 9519-2 Special Guests: Nils Landgren and Magnus Lindgren German Release Date : August 26, 2011 Herbie Hancock is without doubt one of the few remaining greats of jazz as a pianist and composer. Of late he has been playing jazz, rock and pop standards with a number of prominent guests - on “Possibilities” (2005) and most recently on “The Imagine Project” he joined up with global stars like Santana, Sting, Christina Aguilera and Pink to perform a range of popular classics. Now the tables have turned, and rather than Herbie covering the music of other artists, a fan of the 71-year-old has written a series of musical “Letters to Herbie” – ACT’s star Viktoria Tolstoy has recorded 12 songs for (and in most cases by) Herbie Hancock. Viktoria Tolstoy has been a great admirer of Hancock since her early youth and the idea to do a tribute project has been with her for a while. “I think it was in 2004,” says Tolstoy, “at the Jazz Baltica Festival in Salzau, when I had the privilege to share the stage with Herbie and his band, including the amazing Wayne Shorter. As usual, after that there was a big late night jam session going on. I was sitting behind the drums and had just started to play, when someone called ‘Viktoria, Herbie is expecting you – he wants to have dinner with you!’ I immediately dropped the drumsticks and went downstairs, where Herbie and his entire band were already waiting for me. I was seated directly opposite my idol and next to Wayne Shorter.