State and Local Taxation of Financial Institutions:An Opportunity for Reform

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Final Report of the Reconstruction Finance Corporation

FINAL REPORT on the Reconstruction Finance Corporation Pursuant to Section 6(c) Reorganization Plan No. 1 of 1957 SECRETARY OF THE TREASURY UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT FKttJTING OFFICE WASHINGTON 1959 For ale by the Superintendent ef Decutacnti, U-S.GovcnracQt Printing Office Digitized for FRASER http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/ Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Digitized for FRASER http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/ Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis THC SECRETARY OF THE TREASURY WASHINGTON May 6, 1959 Sirs: I have the honor to submit herewith the final report on the Reconstruction Finance Corporation which is required under Section 6 (c) of Reorganization Plan No* 1 of 1957. The report was prepared under the direction of Mr* Laurence B. Robbing, who presently is serving in the capacity of Assistant Secretary of the Treasury. Prior to confirmation in his present position, Mr. Robbins served both as Deputy Administrator and Administrator of the Reconstruction Finance Corporation and directed the liquidation of that Corporation's affairs. Secretary of the Treasury To the President of the Senate To the-Speaker of the House of Representatives iii Digitized for FRASER http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/ Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Digitized for FRASER http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/ Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis FOREWORD The Reconstruction Finance Corporation was among the largest and undoubtedly was the most complex of all Federal lending agen- cies. In its operations it disbursed more than $40 billion, and was conditionally committed to disburse many billions more under guar- anties of loans and investments made by private financial institutions. Organized during a severe economic depression, the RFC passed through periods of recovery, preparedness, war, reconversion, eco- nomic expansion, another war and, finally, stability and prosperity. -

GAO-16-175, Financial Regulation

United States Government Accountability Office Report to Congressional Requesters February 2016 FINANCIAL REGULATION Complex and Fragmented Structure Could Be Streamlined to Improve Effectiveness GAO-16-175 February 2016 FINANCIAL REGULATION Complex and Fragmented Structure Could Be Streamlined to Improve Effectiveness Highlights of GAO-16-175, a report to congressional requesters Why GAO Did This Study What GAO Found The U.S. financial regulatory structure The U.S. financial regulatory structure is complex, with responsibilities has evolved over the past 150 years in fragmented among multiple agencies that have overlapping authorities. As a response to various financial crises result, financial entities may fall under the regulatory authority of multiple and the need to keep pace with regulators depending on the types of activities in which they engage (see figure developments in financial markets and on next page). While the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer products in recent decades. Protection Act (Dodd-Frank Act) made a number of reforms to the financial GAO was asked to review the financial regulatory system, it generally left the regulatory structure unchanged. regulatory structure and any related impacts of fragmentation or overlap. U.S. regulators and others have noted that the structure has contributed to the This report examines the structure of overall growth and stability in the U.S. economy. However, it also has created the financial regulatory system and the challenges to effective oversight. Fragmentation and overlap have created effects of fragmentation and overlap on inefficiencies in regulatory processes, inconsistencies in how regulators oversee regulators’ oversight activities. GAO similar types of institutions, and differences in the levels of protection afforded to reviewed relevant laws and agency consumers. -

Federal Farm Loan Bureau

U. S. TREASURY DEPARTMENT FEDERAL FARM LOAN BUREAU Circular No. 20 THE FEDERAL FARM LOAN ACT AS AMENDED TO JULY 16, 1932 Exclusive of Provisions relating to Federal Intermediate Credit Banks Appendix, containing certain other Acts of the Congress having a direct relation to the Federal Farm Loan Act INDEX ISSUED BY THE FEDERAL FARM LOAN BOARD JULY, 1932 UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 1932 Digitized for FRASER http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/ Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis EDITORIAL NOTE This circular contains all provisions of the Federal Farm Loan Act and amendments thereto relating to Federal land banks, joint stock land banks, and national farm loan associations in effect on July 16, 1932. The provisions of the act have been classified in accordance with the codification thereof in title 12 of the official Code of Laws of the United States of America in Force December 26, 1926, and supplements thereto. In the left margin of this circular opposite each provision is printed the section number of such provision in title 12 of the Code. In the right margin is printed the number of the section of the Federal Farm Loan Act, as amended, of which the pro vision is a part. At the end of each provision is a parenthetical reference to the act of Congress from which the provision was derived and to any subsequent amendatory acts. The symbol “ 12 U. S. C.” refers to United States Code, title 12. The symbol “ F. F. L. Act” refers to the Federal Farm Loan Act, as amended. The official Code has been followed in its editing of the text of the act and amendments thereto, by the omission of “ that55 at the opening of paragraphs, the omission of obsolete provisions, etc. -

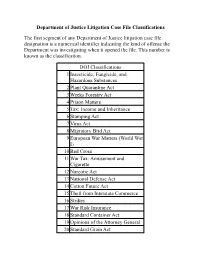

DOJ Classifications for Webpage

Department of Justice Litigation Case File Classifications The first segment of any Department of Justice litigation case file designation is a numerical identifier indicating the kind of offense the Department was investigating when it opened the file. This number is known as the classification. DOJ Classifications 1 Insecticide, Fungicide, and Hazardous Substances 2 Plant Quarantine Act 3 Weeks Forestry Act 4 Prison Matters 5 Tax: Income and Inheritance 6 Stamping Act 7 Virus Act 8 Migratory Bird Act 9 European War Matters (World War I) 10 Red Cross 11 War Tax: Amusement and Cigarette 12 Narcotic Act 13 National Defense Act 14 Cotton Future Act 15 Theft from Interstate Commerce 16 Strikes 17 War Risk Insurance 18 Standard Container Act 19 Opinions of the Attorney General 20 Standard Grain Act 21 Food and Drug (Prosecution) 22 Food and Drug (Seizure) 23 Liquor Violations 24 High Cost of Living 25 Selective Service Act 26 Dyer Act (Automobile Theft) 27 Patents 28 Copyrights 29 National Banking Act 30 Quarantine 31 White Slave Traffic (Mann Act) 32 Federal Building Space 33 Federal Building Sites 34 Lacy Act (Game) 35 Civil Service Act 36 Mail Fraud 37 Bonus Overpayment, World War I 38 Naturalization 39 Immigration 40 Passport and Visa Matters 41 Explosives 42 Desertion from Armed Forces of U.S., Harboring such Deserters 43 Illegal Wearing of Uniform 44 Department of Justice Administrative Files (Closed) 45 Crime on the High Seas 46 Fraud Against the Government 47 Impersonation of Federal Officer 48 Postal Violations 49 Bankruptcy 50 Peonage -

Financial Services and Cybersecurity: the Federal Role

Financial Services and Cybersecurity: The Federal Role Updated March 23, 2016 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R44429 Financial Services and Cybersecurity: The Federal Role Summary Multiple federal and state regulators oversee companies in the financial services industry. Regulatory authority is often directed at particular functions or financial services activities rather than at particular entities or companies. It is, therefore, likely that a financial services company with multiple product lines—deposits, securities, insurance—will find that it must answer to different regulators with respect to particular aspects of its operations. Five federal agencies oversee depository institutions, two regulate securities, several agencies have discrete authority over various segments of the financial sector, and several self-regulatory organizations monitor entities in the securities business. Federal banking regulators (the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, the Federal Reserve, and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation) are required to promulgate safety and soundness standards for all federally insured depository institutions to protect the stability of the nation’s banking system. Some of these standards pertain to cybersecurity issues, including information security, data breaches, and destruction or theft of business records. The federal securities regulators (the Securities and Exchange Commission and the Commodity Futures Trading Commission) have asserted authority over various aspects of cybersecurity in securities markets and those who trade in them. This includes requiring publicly traded financial and nonfinancial corporations to file annual and quarterly reports that provide investors with material information, a category which could include information about cybersecurity risks or breaches. In addition, overseeing the securities industry are certain self-regulatory organizations—private organizations empowered by law or regulation to create and enforce industry rules, including those covering cybersecurity. -

Congressional Record-House House of Representatives

,1933 _CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-HOUSE 4681 as I am concerned, I should be very glad if we could fix a NOMINATIONS time definitely for a vote tomorrow on the nomination. Executive nominations received by the Senate May 31 (legis Mr. McNARY. Let me suggest to the Senator that we lative day of Mdy 29), 1933 recess at this time until 11 o'clock tomorrow, in executive session, and vote upon the confirmation of the nominee to SECRETARIES IN THE DIPLOMATIC SERVICE morrow at 3 o'clock. William F. Cavenaugh, of California, now a Foreign Mr. BARKLEY. Mr. President, I am anxious to have this Service officer, unclassified, and a vice consul of career, to be case disposed of; but if several Senators on the other side also a secretary in the Diplomatic Service of the United are to speak, as indicated by the Senator from Mississippi, States of America. and they are to take all the time until 3 o'clock, and then we Bernard Gufler, of Washington, now a Foreign Service are to vote, I could not enter into any such agreement. I officer, unclassified, and a vice consul of career, to be also want at least time enough to reply to this stuff being dumped a secretary in the Diplomatic Service of the United States into the RECORD. of America. Mr. CLARK. I desire to make a few remarks myself. Louis G. Dreyfus, Jr., of California, now a Foreign Service Mr. HARRISON. Mr. President, would the Senator from officer of class 1 and a consul general, to be also a secretary Oregon be willing that we recess until 11 o'clock, and that in the Diplomatic Service of the United States of America. -

FCA Fiscal Year 2022 Proposed Budget

Farm Credit Administration Fiscal Year 2022 Proposed Budget and Performance Plan Farm Credit Administration FY 2022 Proposed Budget and Performance Plan Table of Contents Part I Fiscal Year 2022 Proposed Budget ................................................................................ 1 Fiscal Year 2022 Budget Overview ................................................................................................. 3 Budget Trends ................................................................................................................................. 8 Assessments ................................................................................................................................... 12 Part II Farm Credit Administration ....................................................................................... 15 Profile of the Farm Credit Administration .................................................................................... 17 FCA Internal Operations............................................................................................................... 20 Ensuring Safety and Soundness ................................................................................................... 30 Developing Regulations and Policies ............................................................................................. 37 Part III Farm Credit System .................................................................................................. 43 Profile of the Farm Credit System .................................................................................................45 -

Evaluating Bank Commercial Paper Placement Activity Under the Glass-Steagall Act

Washington University Law Review Volume 65 Issue 3 January 1987 Evaluating Bank Commercial Paper Placement Activity Under the Glass-Steagall Act Stuart J. Vogelsmeier Washington University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_lawreview Part of the Banking and Finance Law Commons Recommended Citation Stuart J. Vogelsmeier, Evaluating Bank Commercial Paper Placement Activity Under the Glass-Steagall Act, 65 WASH. U. L. Q. 615 (1987). Available at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_lawreview/vol65/iss3/5 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington University Law Review by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EVALUATING BANK COMMERCIAL PAPER PLACEMENT ACTIVITY UNDER THE GLASS-STEAGALL ACT The Glass-Steagall Act' ("The Act") generally prohibits commercial banks from engaging in investment banking activities.2 In response to the recent growth of the financial services market, however, commercial banks have begun to offer services which traditionally the investment banking sector only offered.3 For example, banks now participate in the commercial paper market. Understandably, the investment banking in- dustry has complained about this activity.4 The industry has argued that the Act prohibits any bank involvement in the commercial paper market.5 The Act prohibits banks from underwriting securities.6 Although in Securities Industry Association v. Board of Governors (Bankers Trust) the Supreme Court concluded that commercial paper was a security for pur- poses of Glass-Steagall,7 it has not ruled whether any bank involvement in the commercial paper market constitutes a "per se" violation of the 1. -

The Transparency Theory: an Alternative Approach to Glass-Steagall Issues

The Transparency Theory: An Alternative Approach to Glass-Steagall Issues Michael S. Raab Commercial banks play a central role in our economy," and a complex regulatory system has evolved to monitor their activities.' Among the most controversial components of this system is the Glass-Steagall Act,$ which 1. See Reform of the Nation's Banking and FinancialSystems: Hearings Before the Subcomm. on FinancialInstitutions Supervision, Regulation and Insurance of the House Comm. on Banking, Finance and Urban Affairs, 100th Cong., 1st Sess. 10 (1987) (statement of L. William Seidman, Chairman, Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation) ("[A]ny threat to the banking system is a threat to consumer services and savings, the intermediation process, private sector liquidity, the payment system and, most importantly, the U.S. economy."). 2. Responsibility for regulating the country's more than 14,000 commercial banks is divided among the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC), the Federal Reserve Board, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), state banking agencies, the Securities and Exchange Com- mission (SEC), and the Department of Justice. The OCC regulates banks with charters issued by the federal government ("national banks"). Banks with state-issued charters that are members of the Fed- eral Reserve System (state "member" banks) are regulated by the Federal Reserve Board and their state regulatory agency. State-chartered banks that are not members of the Federal Reserve System (state "non-member" banks) are regulated by their state regulator and, if they are federally insured, by the FDIC. See TASK GROUP ON REGULATION OF FINANCIAL SERVICES, BLUEPRINT FOR RE- FORM: THE REPORT OF THE TASK GROUP ON REGULATION OF FINANCIAL SERVIcES 16, 18-20 (1984). -

Shared Roots: the Federal Reserve System and the Farm Credit System

Shared Roots: The Federal Reserve System and the Farm Credit System James N. Putnam II 1 May 12, 2015 The agricultural credit system, created by the Federal Farm Loan Act, was modeled upon the federal reserve system in its general outline as well as in many details. W. Stull Holt, 1924, p. 8. Introduction On December 23, 1913, President Woodrow Wilson signed the Federal Reserve Act (FRA) into law creating the Federal Reserve System. Just thirty-one months later, on July 17, 1916, he signed the Farm Loan Act (FLA) into law, the first step in creating the Farm Credit System. The Federal Reserve celebrated its Centennial in 2013-14 and the Farm Credit System will do so in 2015-16. The close timing of the passage of the Federal Reserve Act and the Farm Loan Act was no random coincidence. Passage of the Federal Reserve Act was also the opening act of the legislative history of the Farm Loan Act. By reluctantly throwing their support behind the Federal Reserve Act, agrarian advocates gained political IOUs that later helped to ensure passage of the Farm Loan Act. The Federal Reserve Act became the template for the Farm Loan Act, launching a Farm Credit System committed to serving the financial needs of agriculture and rural America. The Federal Reserve System and the Farm Credit System share much common history from the early 1900s: x The enabling Acts for both Systems were instigated by economic events from the preceding decade. Indeed, frustrations well back into the 1800s created momentum for both Acts. -

Farm Credit Act and Other Statutes (PDF)

The Farm Credit Act and other statutes governing the Farm Credit System and the Farm Credit Administration Contents Farm Credit Act of 1971, as amended .............................................................................................................................. 1 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................................. 2 Title I—Farm Credit Banks ......................................................................................................................................... 3 Sec. 1.1. Policy and Objectives.— .................................................................................................................... 3 Sec. 1.2. The Farm Credit System.— ............................................................................................................... 3 Sec. 1.3. Establishment, Charters, Titles, Branches. ......................................................................................... 4 Sec. 1.4. Board of Directors. ............................................................................................................................. 4 Sec. 1.5. General Corporate Powers. ................................................................................................................ 4 Sec. 1.6. Farm Credit Bank Capitalization. ....................................................................................................... 6 Sec. 1.7. Lending Authority. ............................................................................................................................ -

'383.0 ~Congressional .Record--Senate September

'383.0 ~CONGRESSIONAL .RECORD--SENATE SEPTEMBER. 21 REFERENCE OF EXECUTIVE :M.ESSAGES •. - I PROMOTION IN THE PHILIPPINE SCOUTS _ The PRESIDING OFFICER. The Chair refers to _the appro To be major priate comiriittees sundry Executive inesSa.ges received from the Capt. James Cadmus McGovern, Philippine Scouts, from Sep- President of the United States. tember 15, 1929. RECESS Mr. SMOOT. I move that the Senate take a recess until 12 SENATE o'clock noon to~morrow. SATURDAY, Septemher ~1, 19~9 The motion was agreed to; and (at 5 o'clock and 22 minutes p. ru.) the Senate took a recess until · to~morrow, Saturday, (Legislative day of Mon4ay, September 9, 1929) September 21, 1929, at 12 o'clock meridian. - . The Senate met at 12 o'clock meridian, on the expiration of the recess. Mr. JONES. Mr. President, I suggest the absen~e of a NOMINATIONS quorum. Exec-utive nominations received by the Senate September 20 The VICE PRESIDENT. The clerk will call the roll. ( leoislatitve day of September 9), 1929 The legislative clerk called the roll, and the following Senators PuBLic HEALTH SERVICE answered to their names : Allen Fletcher Jones Sackett Asst. Surg. James B. Ryon to be passed assistant surgeon in Ashurst Frazier Kean Schall the Public Health Service, to rank ·as such from October 14, 1929. Barkley George Kendrick Sheppard Black Gillett Keyes Shortridge (Doctor Ryon has passed the examination required by law and Blaine Glenn La Follette Simmons the regulations of the service.) Blease Goff McKellar Smoot Borah Goldsborough McMaster Steck To BE CHIEF OF THE l\fiLITIA BUREAU Bratton Gould McNary Steiwer Brock .