Another Source of Loanable Funds

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mm- Conferences I (5/12/98)

Guide to the Papers of HYDE H. MURRAY LEGISLATION BY SUBJECT • = publication Box File Subject Description Date 85 1 Agricultural Act of 1948 Act- Public Law 897 80th Congress H.R. 6248 1948 85 2 Discussion of Title II of the Agricultural act of 1948 1948 85 3 Hearings before the special subcommittee on 1949 agriculture house of representative 85 4 Bills- H.R. 5345 (agricultural adjustment act), and 1949 a copy of Act- PL 439 81st Congress 85 5 Summary of Principal Provision; Agricultural 1949 Adjustment Act of 1949 85 6 Reports: 1948, - Farm Price Support Program 1949 - Agricultural Act of 1949 - Agricultural Act of 1949: Conference report - Agricultural Bill of 1948: Conference report 85 7 Bills: copies of H.R.6969, 4618, 4523, 4296, 4297, 1975 3543, 3187, 1290, 85 8 Agricultural Act 1949: Mexican Farm Labor Amendments: Amend H.R. 8195 offered by Mr. 1963 Roosevelt; Point of Order—Amendment to Sec. 503 of PL 78, Amendment to H.R. 8195 85 9 Bills– H.R.1836, 2009, 5215, 5195, 5497, 6719, 1963 8195, Corr, and Statement- Explanation of a Draft Bill to Amend the Mexican Labor Program 85 10 Bills (Senate): copy of S1703 1963 85 11 • Article- Lobbyist Use Pressure for Braceros Bill, 1963 Post Oct. 31, 1963 • News Letter- AFBR Official News Letter, Nov. 11, 1963 85 12 Agricultural Act 1949: Mexican Farm Labor Report- Report of Operations of Mexican farm Labor 1963 Program Made Pursuant to Conference Report No. 1449 House of Representatives 84th Congress, first Session, Re Use of Mexican Workers Does Not Depress Farm Wages, Notes, Witness List of Equipment, Supplies and Manpower Subcommittee 85 13 Reports: 1963 - Extension of Mexican Farm Labor Program, Report, Aug 6, 1963 - One- Year Extension of Mexican Farm Labor Program, Report, Sept 6, 1963 BAYLOR COLLECTIONS OF POLITICAL MATERIALS 3/22/2004 W A C O , T E X A S P A G E 1 Guide to the Papers of HYDE H. -

Public Law 102-552 102D Congress an Act Oct

106 STAT. 4102 PUBLIC LAW 102-552—OCT. 28, 1992 Public Law 102-552 102d Congress An Act Oct. 28, 1992 To enhance the financial safety and soundness of the banks and associations of [H.R. 6125] the Farm Credit System, and for other purposes. Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of Farm Credit the United States of America in Congress assembled, Banks and Associations SECTION 1. SHORT TITLE; TABLE OF CONTENTS. Safety and Soundness Act (a) SHORT TITLE.—This Act mav be cited as the "Farm Credit of 1992. Banks and Associations Safety and Soundness Act of 1992". 12 use 2001 (b) TABLE OF CONTENTS.—The table of contents of this Act (S note. is as follows: Sec. 1. Short title; table of contents. Sec. 2. References to the Farm Credit Act of 1971. TITLE I—IMPROVEMENTS TO FARM CREDIT SYSTEM SAFETY AND SOUNDNESS Sec. 101. Definition of permanent capital. Sec. 102. Qualifications of Farm Credit Administration Board members. TITLE II—FARM CREDIT SYSTEM INSURANCE CORPORATION Sec. 201. Farm Credit System Insurance Corporation. Sec. 202. Statutory successor to Assistance Board agreements. Sec. 203. Use of Farm Credit Administration personnel. Sec. 204. GAO reports on risk-based insurance premiums, access to association cap ital, supplemental premiums, and consolidation. TITLE III—REPAYMENT OF FARM CREDIT SYSTEM DEBT OBLIGATIONS Sec. 301. Capital preservation. Sec. 302. Preferred stock. -^ Sec. 303. Systemwide repajnnaent obligation. Sec. 304. Repayment of Treasury-paid interest. Sec. 305. Transfer of obligations from associations to banks; other matters. Sec. 306. Defaults. Sec. 307. Authority of Financial Assistance Corporation. -

Federal Statutes of Special Importance to Farmer Cooperatives

Federal Statutes of Special Importance to Farmer Cooperatives 115TH CONGRESS EDITION Cooperative Information Report 66 Rural Business-Cooperative Service United States Department of Agriculture Federal Statutes of Special Importance to Farmer Cooperatives 115TH CONGRESS EDITION Revised August 2017 Federal Statutes of Special Importance to Farmer Cooperatives provides a single, readily available source of laws that address how cooperatives conduct their business. It was originally compiled by Donald A. Frederick and LaTonya St. Clair, and includes all references to cooperatives in Federal law that are significant to cooperatives. This update reflects laws that are current as of August 2017. Several of the citations in the compilation pay deference to popular convention. In the antitrust portion of the report, the section number at the start of each provision is the number in the original act; the U.S. Code uses the codified section number found in parentheses ( ) throughout. Also, the laws in the antitrust section are presented in chronological order by date of enactment; in other sections the laws are arranged in numerical order by title and section, as they appear in the Code. The headers, which appear in bold letters, are those Federal Statutes of Special Importance that appear in the official Code. to Farmer Cooperatives (Cooperative Information Report 65) was originally If you would like to suggest any materials that could be added compiled by Donald A. Frederick and to make the report more useful or if you have found any LaTonya St. Clair in 1990 and was last errors, please contact Meegan Moriarty at Rural Business updated in 2007. -

Final Report of the Reconstruction Finance Corporation

FINAL REPORT on the Reconstruction Finance Corporation Pursuant to Section 6(c) Reorganization Plan No. 1 of 1957 SECRETARY OF THE TREASURY UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT FKttJTING OFFICE WASHINGTON 1959 For ale by the Superintendent ef Decutacnti, U-S.GovcnracQt Printing Office Digitized for FRASER http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/ Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Digitized for FRASER http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/ Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis THC SECRETARY OF THE TREASURY WASHINGTON May 6, 1959 Sirs: I have the honor to submit herewith the final report on the Reconstruction Finance Corporation which is required under Section 6 (c) of Reorganization Plan No* 1 of 1957. The report was prepared under the direction of Mr* Laurence B. Robbing, who presently is serving in the capacity of Assistant Secretary of the Treasury. Prior to confirmation in his present position, Mr. Robbins served both as Deputy Administrator and Administrator of the Reconstruction Finance Corporation and directed the liquidation of that Corporation's affairs. Secretary of the Treasury To the President of the Senate To the-Speaker of the House of Representatives iii Digitized for FRASER http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/ Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Digitized for FRASER http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/ Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis FOREWORD The Reconstruction Finance Corporation was among the largest and undoubtedly was the most complex of all Federal lending agen- cies. In its operations it disbursed more than $40 billion, and was conditionally committed to disburse many billions more under guar- anties of loans and investments made by private financial institutions. Organized during a severe economic depression, the RFC passed through periods of recovery, preparedness, war, reconversion, eco- nomic expansion, another war and, finally, stability and prosperity. -

GAO-16-175, Financial Regulation

United States Government Accountability Office Report to Congressional Requesters February 2016 FINANCIAL REGULATION Complex and Fragmented Structure Could Be Streamlined to Improve Effectiveness GAO-16-175 February 2016 FINANCIAL REGULATION Complex and Fragmented Structure Could Be Streamlined to Improve Effectiveness Highlights of GAO-16-175, a report to congressional requesters Why GAO Did This Study What GAO Found The U.S. financial regulatory structure The U.S. financial regulatory structure is complex, with responsibilities has evolved over the past 150 years in fragmented among multiple agencies that have overlapping authorities. As a response to various financial crises result, financial entities may fall under the regulatory authority of multiple and the need to keep pace with regulators depending on the types of activities in which they engage (see figure developments in financial markets and on next page). While the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer products in recent decades. Protection Act (Dodd-Frank Act) made a number of reforms to the financial GAO was asked to review the financial regulatory system, it generally left the regulatory structure unchanged. regulatory structure and any related impacts of fragmentation or overlap. U.S. regulators and others have noted that the structure has contributed to the This report examines the structure of overall growth and stability in the U.S. economy. However, it also has created the financial regulatory system and the challenges to effective oversight. Fragmentation and overlap have created effects of fragmentation and overlap on inefficiencies in regulatory processes, inconsistencies in how regulators oversee regulators’ oversight activities. GAO similar types of institutions, and differences in the levels of protection afforded to reviewed relevant laws and agency consumers. -

Federal Farm Loan Bureau

U. S. TREASURY DEPARTMENT FEDERAL FARM LOAN BUREAU Circular No. 20 THE FEDERAL FARM LOAN ACT AS AMENDED TO JULY 16, 1932 Exclusive of Provisions relating to Federal Intermediate Credit Banks Appendix, containing certain other Acts of the Congress having a direct relation to the Federal Farm Loan Act INDEX ISSUED BY THE FEDERAL FARM LOAN BOARD JULY, 1932 UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 1932 Digitized for FRASER http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/ Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis EDITORIAL NOTE This circular contains all provisions of the Federal Farm Loan Act and amendments thereto relating to Federal land banks, joint stock land banks, and national farm loan associations in effect on July 16, 1932. The provisions of the act have been classified in accordance with the codification thereof in title 12 of the official Code of Laws of the United States of America in Force December 26, 1926, and supplements thereto. In the left margin of this circular opposite each provision is printed the section number of such provision in title 12 of the Code. In the right margin is printed the number of the section of the Federal Farm Loan Act, as amended, of which the pro vision is a part. At the end of each provision is a parenthetical reference to the act of Congress from which the provision was derived and to any subsequent amendatory acts. The symbol “ 12 U. S. C.” refers to United States Code, title 12. The symbol “ F. F. L. Act” refers to the Federal Farm Loan Act, as amended. The official Code has been followed in its editing of the text of the act and amendments thereto, by the omission of “ that55 at the opening of paragraphs, the omission of obsolete provisions, etc. -

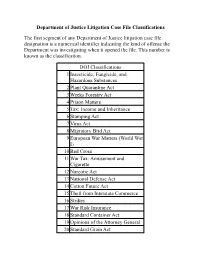

DOJ Classifications for Webpage

Department of Justice Litigation Case File Classifications The first segment of any Department of Justice litigation case file designation is a numerical identifier indicating the kind of offense the Department was investigating when it opened the file. This number is known as the classification. DOJ Classifications 1 Insecticide, Fungicide, and Hazardous Substances 2 Plant Quarantine Act 3 Weeks Forestry Act 4 Prison Matters 5 Tax: Income and Inheritance 6 Stamping Act 7 Virus Act 8 Migratory Bird Act 9 European War Matters (World War I) 10 Red Cross 11 War Tax: Amusement and Cigarette 12 Narcotic Act 13 National Defense Act 14 Cotton Future Act 15 Theft from Interstate Commerce 16 Strikes 17 War Risk Insurance 18 Standard Container Act 19 Opinions of the Attorney General 20 Standard Grain Act 21 Food and Drug (Prosecution) 22 Food and Drug (Seizure) 23 Liquor Violations 24 High Cost of Living 25 Selective Service Act 26 Dyer Act (Automobile Theft) 27 Patents 28 Copyrights 29 National Banking Act 30 Quarantine 31 White Slave Traffic (Mann Act) 32 Federal Building Space 33 Federal Building Sites 34 Lacy Act (Game) 35 Civil Service Act 36 Mail Fraud 37 Bonus Overpayment, World War I 38 Naturalization 39 Immigration 40 Passport and Visa Matters 41 Explosives 42 Desertion from Armed Forces of U.S., Harboring such Deserters 43 Illegal Wearing of Uniform 44 Department of Justice Administrative Files (Closed) 45 Crime on the High Seas 46 Fraud Against the Government 47 Impersonation of Federal Officer 48 Postal Violations 49 Bankruptcy 50 Peonage -

Agriculture: a Glossary of Terms, Programs, and Laws, 2005 Edition

Agriculture: A Glossary of Terms, Programs, and Laws, 2005 Edition Updated June 16, 2005 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov 97-905 Agriculture: A Glossary of Terms, Programs, and Laws, 2005 Edition Summary The complexities of federal farm and food programs have generated a unique vocabulary. Common understanding of these terms (new and old) is important to those involved in policymaking in this area. For this reason, the House Agriculture Committee requested that CRS prepare a glossary of agriculture and related terms (e.g., food programs, conservation, forestry, environmental protection, etc.). Besides defining terms and phrases with specialized meanings for agriculture, the glossary also identifies acronyms, abbreviations, agencies, programs, and laws related to agriculture that are of particular interest to the staff and Members of Congress. CRS is releasing it for general congressional use with the permission of the Committee. The approximately 2,500 entries in this glossary were selected in large part on the basis of Committee instructions and the informed judgment of numerous CRS experts. Time and resource constraints influenced how much and what was included. Many of the glossary explanations have been drawn from other published sources, including previous CRS glossaries, those published by the U.S. Department of Agriculture and other federal agencies, and glossaries contained in the publications of various organizations, universities, and authors. In collecting these definitions, the compilers discovered that many terms have diverse specialized meanings in different professional settings. In this glossary, the definitions or explanations have been written to reflect their relevance to agriculture and recent changes in farm and food policies. -

Financial Services and Cybersecurity: the Federal Role

Financial Services and Cybersecurity: The Federal Role Updated March 23, 2016 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R44429 Financial Services and Cybersecurity: The Federal Role Summary Multiple federal and state regulators oversee companies in the financial services industry. Regulatory authority is often directed at particular functions or financial services activities rather than at particular entities or companies. It is, therefore, likely that a financial services company with multiple product lines—deposits, securities, insurance—will find that it must answer to different regulators with respect to particular aspects of its operations. Five federal agencies oversee depository institutions, two regulate securities, several agencies have discrete authority over various segments of the financial sector, and several self-regulatory organizations monitor entities in the securities business. Federal banking regulators (the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, the Federal Reserve, and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation) are required to promulgate safety and soundness standards for all federally insured depository institutions to protect the stability of the nation’s banking system. Some of these standards pertain to cybersecurity issues, including information security, data breaches, and destruction or theft of business records. The federal securities regulators (the Securities and Exchange Commission and the Commodity Futures Trading Commission) have asserted authority over various aspects of cybersecurity in securities markets and those who trade in them. This includes requiring publicly traded financial and nonfinancial corporations to file annual and quarterly reports that provide investors with material information, a category which could include information about cybersecurity risks or breaches. In addition, overseeing the securities industry are certain self-regulatory organizations—private organizations empowered by law or regulation to create and enforce industry rules, including those covering cybersecurity. -

Congressional Record-House House of Representatives

,1933 _CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-HOUSE 4681 as I am concerned, I should be very glad if we could fix a NOMINATIONS time definitely for a vote tomorrow on the nomination. Executive nominations received by the Senate May 31 (legis Mr. McNARY. Let me suggest to the Senator that we lative day of Mdy 29), 1933 recess at this time until 11 o'clock tomorrow, in executive session, and vote upon the confirmation of the nominee to SECRETARIES IN THE DIPLOMATIC SERVICE morrow at 3 o'clock. William F. Cavenaugh, of California, now a Foreign Mr. BARKLEY. Mr. President, I am anxious to have this Service officer, unclassified, and a vice consul of career, to be case disposed of; but if several Senators on the other side also a secretary in the Diplomatic Service of the United are to speak, as indicated by the Senator from Mississippi, States of America. and they are to take all the time until 3 o'clock, and then we Bernard Gufler, of Washington, now a Foreign Service are to vote, I could not enter into any such agreement. I officer, unclassified, and a vice consul of career, to be also want at least time enough to reply to this stuff being dumped a secretary in the Diplomatic Service of the United States into the RECORD. of America. Mr. CLARK. I desire to make a few remarks myself. Louis G. Dreyfus, Jr., of California, now a Foreign Service Mr. HARRISON. Mr. President, would the Senator from officer of class 1 and a consul general, to be also a secretary Oregon be willing that we recess until 11 o'clock, and that in the Diplomatic Service of the United States of America. -

Historical Introduction to the Farm Credit System: Structure and Authorities, 1971 to Present

Reprinted and Distributed with Permission of the Drake Journal of Agricultural Law HISTORICAL INTRODUCTION TO THE FARM CREDIT SYSTEM: STRUCTURE AND AUTHORITIES, 1971 TO PRESENT Richard L. Manner† I. Introduction .................................................................................................... 280 II. Snapshot of the System Under the Original 1971 Act .................................. 281 A. Overview of System Structure: The Traditional Twelve Farm Credit Districts ................................................................................. 281 B. Additional Organizational and Structural Aspects of the Banks and Associations ............................................................................... 286 C. Eligibility to Borrow .......................................................................... 288 D. Non-Loan Authorities ........................................................................ 289 E. Other Farm Credit System Institutions and Non-Farm Credit System Affiliates .............................................................................. 290 1. Service Organizations ................................................................. 290 2. The Farm Credit Councils ........................................................... 292 III. Restructuring of the System Under the Agricultural Credit Act of 1987 ..... 292 A. Structural Change under the 1987 Amendments ............................... 293 1. The Formation of the Farm Credit Banks ................................... 293 2. The Formation -

Previewing a 2007 Farm Bill

Previewing a 2007 Farm Bill Updated January 3, 2007 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov RL33037 Previewing a 2007 Farm Bill Summary Federal farm support, food assistance, agricultural trade, marketing, and rural development policies are governed by a variety of separate laws. However, many of these laws periodically are evaluated, revised, and renewed through an omnibus, multi-year “farm bill.” The Farm Security and Rural Investment Act of 2002 (P.L. 107-171) was the most recent omnibus farm bill, and many of its provisions expire in 2007, so reauthorization is expected to be addressed in the first session of the 110th Congress. The heart of every omnibus farm bill is farm income and commodity price support policy— namely, the methods and levels of support that the federal government provides to agricultural producers. However, farm bills typically include titles on agricultural trade and foreign food aid, conservation and environment, forestry, domestic food assistance (primarily food stamps), agricultural credit, rural development, agricultural research and education, and marketing-related programs. Often, such “miscellaneous” provisions as food safety, marketing orders, animal health and welfare, and energy are added. This omnibus nature of the farm bill creates a broad coalition of support among sometimes conflicting interests for policies that, individually, might not survive the legislative process. The scope and direction of a new farm bill may be shaped by such factors as financial conditions in the agricultural economy, competition among various interests, international trade obligations, and—possibly most important—a tight limit on federal funds. Among the thorniest issues may be future farm income and commodity price support.