The Bush Administration's Torture Policy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Government Turns the Other Way As Judges Make Findings About Torture and Other Abuse

USA SEE NO EVIL GOVERNMENT TURNS THE OTHER WAY AS JUDGES MAKE FINDINGS ABOUT TORTURE AND OTHER ABUSE Amnesty International Publications First published in February 2011 by Amnesty International Publications International Secretariat Peter Benenson House 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW United Kingdom www.amnesty.org Copyright Amnesty International Publications 2011 Index: AMR 51/005/2011 Original Language: English Printed by Amnesty International, International Secretariat, United Kingdom All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publishers. Amnesty International is a global movement of 2.2 million people in more than 150 countries and territories, who campaign on human rights. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights instruments. We research, campaign, advocate and mobilize to end abuses of human rights. Amnesty International is independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion. Our work is largely financed by contributions from our membership and donations CONTENTS Introduction ................................................................................................................. 1 Judges point to human rights violations, executive turns away ........................................... 4 Absence -

Global War on Terror

SADAT MACRO 9/14/2009 8:38:06 PM A PRESUMPTION OF GUILT: THE UNLAWFUL ENEMY COMBATANT AND THE U.S. WAR ON TERROR * LEILA NADYA SADAT I. INTRODUCTION Since the advent of the so-called “Global War on Terror,” the United States of America has responded to the crimes carried out on American soil that day by using or threatening to use military force against Afghanistan, Iraq, Iran, North Korea, Syria, and Pakistan. The resulting projection of American military power resulted in the overthrow of two governments – the Taliban regime in Afghanistan, the fate of which remains uncertain, and Saddam Hussein’s regime in Iraq – and “war talk” ebbs and flows with respect to the other countries on the U.S. government’s “most wanted” list. As I have written elsewhere, the Bush administration employed a legal framework to conduct these military operations that was highly dubious – and hypocritical – arguing, on the one hand, that the United States was on a war footing with terrorists but that, on the other hand, because terrorists are so-called “unlawful enemy combatants,” they were not entitled to the protections of the laws of war as regards their detention and treatment.1 The creation of this euphemistic and novel term – the “unlawful enemy combatant” – has bewitched the media and even distinguished justices of the United States Supreme Court. It has been employed to suggest that the prisoners captured in this “war” are not entitled to “normal” legal protections, but should instead be subjected to a régime d’exception – an extraordinary regime—created de novo by the Executive branch (until it was blessed by Congress in the Military * Henry H. -

Interrogation, Detention, and Torture DEBORAH N

Finding Effective Constraints on Executive Power: Interrogation, Detention, and Torture DEBORAH N. PEARLSTEIN* INTRODUCTION .....................................................................................................1255 I. EXECUTIVE POLICY AND PRACTICE: COERCIVE INTERROGATION AND T O RTU RE ....................................................................................................1257 A. Vague or Unlawful Guidance................................................................ 1259 B. Inaction .................................................................................................1268 C. Resources, Training, and a Plan........................................................... 1271 II. ExECuTrVE LIMITs: FINDING CONSTRAINTS THAT WORK ...........................1273 A. The ProfessionalM ilitary...................................................................... 1274 B. The Public Oversight Organizationsof Civil Society ............................1279 C. Activist Federal Courts .........................................................................1288 CONCLUSION ........................................................................................................1295 INTRODUCTION While the courts continue to debate the limits of inherent executive power under the Federal Constitution, the past several years have taught us important lessons about how and to what extent constitutional and sub-constitutional constraints may effectively check the broadest assertions of executive power. Following the publication -

Historical Dictionary of Air Intelligence

Historical Dictionaries of Intelligence and Counterintelligence Jon Woronoff, Series Editor 1. British Intelligence, by Nigel West, 2005. 2. United States Intelligence, by Michael A. Turner, 2006. 3. Israeli Intelligence, by Ephraim Kahana, 2006. 4. International Intelligence, by Nigel West, 2006. 5. Russian and Soviet Intelligence, by Robert W. Pringle, 2006. 6. Cold War Counterintelligence, by Nigel West, 2007. 7. World War II Intelligence, by Nigel West, 2008. 8. Sexspionage, by Nigel West, 2009. 9. Air Intelligence, by Glenmore S. Trenear-Harvey, 2009. Historical Dictionary of Air Intelligence Glenmore S. Trenear-Harvey Historical Dictionaries of Intelligence and Counterintelligence, No. 9 The Scarecrow Press, Inc. Lanham, Maryland • Toronto • Plymouth, UK 2009 SCARECROW PRESS, INC. Published in the United States of America by Scarecrow Press, Inc. A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc. 4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706 www.scarecrowpress.com Estover Road Plymouth PL6 7PY United Kingdom Copyright © 2009 by Glenmore S. Trenear-Harvey All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Trenear-Harvey, Glenmore S., 1940– Historical dictionary of air intelligence / Glenmore S. Trenear-Harvey. p. cm. — (Historical dictionaries of intelligence and counterintelligence ; no. 9) Includes bibliographical references. ISBN-13: 978-0-8108-5982-1 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-8108-5982-3 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-13: 978-0-8108-6294-4 (eBook) ISBN-10: 0-8108-6294-8 (eBook) 1. -

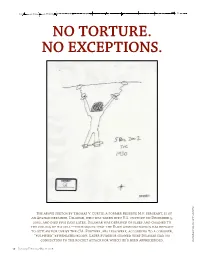

No Torture. No Exceptions

NO TORTURE. NO EXCEPTIONS. The above sketch by Thomas V. Curtis, a former Reserve M.P. sergeant, is of New York Times an Afghan detainee, Dilawar, who was taken into U.S. custody on December 5, 2002, and died five days later. Dilawar was deprived of sleep and chained to the ceiling of his cell—techniques that the Bush administration has refused to outlaw for use by the CIA. Further, his legs were, according to a coroner, “pulpified” by repeated blows. Later evidence showed that Dilawar had no connection to the rocket attack for which he’d been apprehended. A sketch by Thomas Curtis, V. a Reserve M.P./The 16 January/February/March 2008 Introduction n most issues of the Washington Monthly, we favor ar- long-term psychological effects also haunt patients—panic ticles that we hope will launch a debate. In this issue attacks, depression, and symptoms of post-traumatic-stress Iwe seek to end one. The unifying message of the ar- disorder. It has long been prosecuted as a crime of war. In our ticles that follow is, simply, Stop. In the wake of Septem- view, it still should be. ber 11, the United States became a nation that practiced Ideally, the election in November would put an end to torture. Astonishingly—despite the repudiation of tor- this debate, but we fear it won’t. John McCain, who for so ture by experts and the revelations of Guantanamo and long was one of the leading Republican opponents of the Abu Ghraib—we remain one. As we go to press, President White House’s policy on torture, voted in February against George W. -

Usa Amnesty International's Supplementary Briefing To

AI Index: AMR 51/061/2006 3 May 2006 USA AMNESTY INTERNATIONAL’S SUPPLEMENTARY BRIEFING TO THE UN COMMITTEE AGAINST TORTURE This briefing includes further information on the implementation by the United States of America (USA) of its obligations under the UN Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (Convention; UN Convention against Torture), with regard to the forthcoming consideration by the UN Committee Against Torture (the Committee) of the USA’s second periodic report.(1) The briefing updates Amnesty International’s concerns with regard to US "war on terror" detention, interrogation and related policies, as outlined in its preliminary briefing of August 2005, and provides additional information on domestic policies and practice. US OBLIGATIONS UNDER THE CONVENTION WITH RESPECT TO DETAINEES HELD IN THE CONTEXT OF THE "WAR ON TERROR" 1. General supplementary observations on definitions of torture and use of torture under interrogation, including deaths in custody (Articles 1 and 16) Evidence continues to emerge of widespread torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment of detainees held in US custody in Afghanistan, Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, Iraq and other locations. While the government continues to assert that abuses resulted for the most part from the actions of a few "aberrant" soldiers and lack of oversight, there is clear evidence that much of the ill-treatment has stemmed directly from officially santioned procedures and policies, including interrogation techniques approved by Secretary of Defense Rumsfeld for use in Guantánamo and later exported to Iraq.(2) While it seems that some practices, such as "waterboarding", were reserved for high value detainees, others appear to have been routinely applied during detentions and interrogations in Afghanistan, Guantánamo and Iraq. -

ANNEX a Some Publicly Known Deaths of Detainees in U.S

ANNEX A Some Publicly Known Deaths of Detainees in U.S. Custody in Afghanistan and Iraq ACLU-RDI 6826 p.1 Annex A: Some Publicly Known Deaths of Detainees in U.S. Custody in 1 Afghanistan and Iraq No. Name Location Cause of Circumstances Surrounding Death and Date Death 1. Mohammed Near Lwara, Death by Blunt Army Criminal Investigation Division found Sayari Afghanistan Force Injuries probable cause to believe that the commander and Aug. 28, 2002 three other members of Operational Detachment- Alpha 343, 3rd Special Forces Group, had committed the offenses of murder and conspiracy when they lured Mohamed Sayari, an Afghan civilian, into a roadblock, detained him, and killed him. Investigation further found probable cause to believe that a fifth Special Forces soldier had been an accessory after the fact and that the team's commander had instructed a soldier to destroy incriminating photographs of Sayari’s body. No court-martial or Article 32 hearing was convened. One soldier was given a written reprimand. None of the others received any punishment at all.2 2. Name Kabul, Death by The CIA was reportedly involved in the killing of a unknown Afghanistan Hypothermia detainee in Afghanistan. A CIA case officer at the Nov. 2002 “Salt Pit,” a secret U.S.-run prison just north of Kabul, ordered guards to “strip naked an uncooperative young Afghan detainee, chain him to the concrete floor and leave him there overnight without blankets,” the Washington Post reported after interviewing four government officials familiar with the case. According to the article, Afghan guards “paid by the CIA and working under CIA supervision” dragged the prisoner around the concrete floor of the facility, “bruising and scraping his skin,” before placing him in a cell for the night without clothes. -

America's Illicit Affair with Torture

AMERICA’S ILLICIT AFFAIR WITH TORTURE David Luban1 Keynote address to the National Consortium of Torture Treatment ProGrams Washington, D.C., February 13, 2013 I am deeply honored to address this Group. The work you do is incredibly important, sometimes disheartening, and often heartbreaking. Your clients and patients have been alone and terrified on the dark side of the moon. You help them return to the company of humankind on Earth. To the outside world, your work is largely unknown and unsung. Before saying anything else, I want to salute you for what you do and offer you my profound thanks. I venture to guess that all the people you treat, or almost all, come from outside the United States. Many of them fled to America seekinG asylum. In the familiar words of the law, they had a “well-founded fear of persecution”—well- founded because their own Governments had tortured them. They sought refuge in the United States because here at last they would be safe from torture. Largely, they were right—although this morninG I will suGGest that if we peer inside American prisons, and understand that mental torture is as real as physical torture, they are not as riGht as they hoped. But it is certainly true that the most obvious forms of political torture and repression are foreign to the United States. After all, our constitution forbids cruel and unusual punishments, and our Supreme Court has declared that coercive law enforcement practices that “shock the conscience” are unconstitutional. Our State Department monitors other countries for torture. -

The Fundamental Paradoxes of Modern Warfare in Al Maqaleh V

PAINTING OURSELVES INTO A CORNER: THE FUNDAMENTAL PARADOXES OF MODERN WARFARE IN AL MAQALEH V. GATES Ashley C. Nikkel* See how few of the cases of the suspension of the habeas corpus law, have been worthy of that suspension. They have been either real treason, wherein the parties might as well have been charged at once, or sham plots, where it was shameful they should ever have been suspected. Yet for the few cases wherein the suspension of the habeas corpus has done real good, that operation is now become habitual and the minds of the nation almost prepared to live under its constant suspension.1 INTRODUCTION On a cold December morning in 2002, United States military personnel entered a small wire cell at Bagram Airfield, in the Parwan province of Afghan- istan. There, they found Dilawar, a 20-year-old Afghan taxi driver, hanging naked and dead from the ceiling.2 The air force medical examiner who per- formed Dilawar’s autopsy reported his legs had been beaten so many times the tissue was “falling apart” and “had basically been pulpified.”3 The medical examiner ruled his death a homicide, the result of an interrogation lasting four days as Dilawar stood naked, his arms shackled over his head while U.S. inter- rogators performed the “common peroneal strike,” a debilitating blow to the side of the leg above the knee.4 The U.S. military detained Dilawar because he * J.D. Candidate, 2012, William S. Boyd School of Law, Las Vegas; B.A., 2009, University of Nevada, Reno. The Author would like to thank Professor Christopher L. -

2018.12.03 Bonner Soufan Complaint Final for Filing 4

Case 1:18-cv-11256 Document 1 Filed 12/03/18 Page 1 of 19 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - X : : RAYMOND BONNER and ALEX GIBNEY, Case No. 18-cv-11256 : Plaintiffs, : : -against- : : COMPLAINT CENTRAL INTELLIGENCE AGENCY, : : Defendant. : : - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - X INTRODUCTION 1. This complaint for declaratory relief arises out of actions taken by defendant Central Intelligence Agency (“CIA”) that have effectively gagged the speech of former Federal Bureau of Investigation (“FBI”) Special Agent Ali Soufan in violation of the First Amendment to the United States Constitution. The gag imposed upon Mr. Soufan is part of a well-documented effort by the CIA to mislead the American public about the supposedly valuable effects of torture, an effort that has included deceptive and untruthful statements made by the CIA to Executive and Legislative Branch leaders. On information and belief, the CIA has silenced Mr. Soufan because his speech would further refute the CIA’s false public narrative about the efficacy of torture. 2. In 2011, Mr. Soufan published a personal account of his service as a top FBI interrogator in search of information about al-Qaeda before and after the 9/11 terrorist attacks. Soufan’s original manuscript discussed, among other things, his role in the FBI’s interrogation of a high-value detainee named Zayn Al-Abidin Muhammed Husayn, more commonly known as Abu Zubaydah. Soufan was the FBI’s lead interrogator of Zubaydah while he was being held at Case 1:18-cv-11256 Document 1 Filed 12/03/18 Page 2 of 19 a secret CIA black site. -

BLACK SIGHTS by Michael Mccanne, June 1, 2018

BLACK SIGHTS By Michael McCanne, June 1, 2018 In December 2003, Macedonian police detained an unemployed German car salesman named Khaled el-Masri as he entered the country for vacation. They held him in a hotel room for twenty-three days, interrogating him about terrorism. Then he was blindfolded and shackled, injected with drugs, and put on a plane. When he came to, he was in a dark concrete cell and the air outside felt warmer than it had in Eastern Europe. He eventually learned that he was in Afghanistan, in the Salt Pit—a former brick factory northwest of Kabul that had been converted into a secret prison. The CIA took custody of el-Masri because his name was nearly identical to that of an Al Qaeda operative. After five months of brutal interrogations, his captors realized their mistake, put him back on a plane—blindfolded and shackled—and flew him to Albania. They left him on a rural road near the border.1 After 9/11, the Bush Administration set up a network of sites around the world to hold suspected terrorists outside the protection of US law. Some were kept secret, like the Salt Pit, while others quickly became infamous, like Guantánamo Bay. The CIA created a system to snatch terror suspects and transport them to these prisons, a process called extraordinary rendition. Two recent photobooks offer an aesthetic record of this extrajudicial apparatus. Debi Cornwall’s Welcome to Camp America: Inside Guantánamo Bay focuses on that detention center, while Edmund Clark and Crofton Black’s Negative Publicity: Artefacts of Extraordinary Rendition focuses on the now-defunct network of CIA secret prisons known as “black sites.” Welcome to Camp America operates by way of delicate juxtaposition. -

The Taint of Torture: the Roles of Law and Policy in Our Descent to the Dark Side

Georgetown University Law Center Scholarship @ GEORGETOWN LAW 2012 The Taint of Torture: The Roles of Law and Policy in Our Descent to the Dark Side David Cole Georgetown University Law Center, [email protected] Georgetown Public Law and Legal Theory Research Paper No. 12-054 This paper can be downloaded free of charge from: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub/908 http://ssrn.com/abstract=2040866 49 Hous. L. Rev. 53-69 (2012) This open-access article is brought to you by the Georgetown Law Library. Posted with permission of the author. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub Part of the Human Rights Law Commons, Military, War, and Peace Commons, and the National Security Law Commons Do Not Delete 4/8/2012 2:44 AM ARTICLE THE TAINT OF TORTURE: THE ROLES OF LAW AND POLICY IN OUR DESCENT TO THE DARK SIDE David Cole* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................ 53 II.TORTURE AND CRUELTY: A MATTER OF LAW OR POLICY? ....... 55 III.ACCOUNTABILITY AND LEGAL VIOLATIONS ............................. 62 IV.THE LAW AND POLICY OF DETENTION AND TARGETING.......... 64 I. INTRODUCTION Philip Zelikow has provided a fascinating account of how officials in the U.S. government during the “War on Terror” authorized torture and cruel treatment of human beings whom they labeled “high value al Qaeda detainee[s],” “enemy combatants,” or “the worst of the worst.”1 Professor Zelikow * Professor, Georgetown Law. 1. Philip Zelikow, Codes of Conduct for a Twilight War, 49 HOUS. L. REV. 1, 22–24 (2012) (providing an in-depth analysis of the decisions made by the Bush Administration in implementing interrogation policies and practices in the period immediately following September 11, 2001); see Military Commissions Act of 2006, Pub.