AIDS in Cultural Bodies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arts and Culture in Columbus Creating Competitive Advantage and Community Benefit Columbus Cultural Leadership Consortium Member Organizations

A COMMUNITY DISCUSSION PAPER presented by: COLUMBUS CULTURAL LEADERSHIP CONSORTIUM SEPTEMBER 21, 2006 Arts and Culture in Columbus Creating Competitive Advantage and Community Benefit Columbus Cultural Leadership Consortium Member Organizations BalletMet Center of Science and Industry (COSI) Columbus Association for the Performing Arts (CAPA) Columbus Children’s Theatre Columbus Museum of Art Columbus Symphony Orchestra Contemporary American Theatre Company (CATCO) Franklin Park Conservatory Greater Columbus Arts Council (GCAC) Jazz Arts Group The King Arts Complex Opera Columbus Phoenix Theatre ProMusica Chamber Orchestra Thurber House Wexner Center for the Arts COLUMBUS CULTURAL LEADERSHIP CONSORTIUM Table of Contents Executive Summary . 2 Introduction . 4 Purpose . 4 State of the Arts . 5 Quality Proposition . 5 Finances at a Glance . 9 Partnerships as Leverage . 11 Public Value and Community Advantage . 13 Education and Outreach . 14 Economic Development . 17 Community Building . 21 Marketing . 23 Imagining Enhanced Community Benefit . 24 Vision and Desired Outcomes . 24 Strategic Timeline for Reaching Our Vision . 28 “The Crossroads” Conclusion . 28 Table 1: CCLC Member Organization Key Products and Services . 29 Table 2: CCLC Member Organization Summary Information . 31 Table 3: CCLC Member Organization Offerings at a Glance . 34 Endnotes . 35 Bibliography . 37 Issued September 21, 2006 1 COLUMBUS CULTURAL LEADERSHIP CONSORTIUM Executive Summary Desired Outcomes Comprised of 16 organizations, the Columbus 1. Culture and arts will form a significant Cultural Leadership Consortium (CCLC, or “the differentiator for our city and contribute to its consortium”) was created early in 2006 to bring overall economic development. organization and voice to the city’s major cultural and artistic “anchor” institutions, with a focus on It is sobering to see the results of a 2005 study policy and strategy in both the short term and over conducted by the Columbus Chamber, indicating the long haul. -

Pearl Cleage

March 17 – April 12, 2015, on the IRT Upperstage STUDY GUIDE edited by Richard J Roberts & Milicent Wright with contributions by Janet Allen, Lou Bellamy Vicki Smith, Matthew J. LeFebvre, Don Darnutzer Indiana Repertory Theatre 140 West Washington Street • Indianapolis, Indiana 46204 Janet Allen, Executive Artistic Director Suzanne Sweeney, Managing Director www.irtlive.com YOUTH AUDIENCE & SEASON SPONSOR ASSOCIATE SPONSOR MATINEE PROGRAMS 2014-2015 SPONSOR 2 INDIANA REPERTORY THEATRE What I Learned in Paris by Pearl Cleage 1973 Atlanta. The politics of race, class, and gender are rapidly transforming as the city elects its first black mayor. What better time to begin a romantic escapade? As our lovers make history, old flames rekindle and new ones ignite in this masterfully funny play by one of the country’s leading African-American writers. Estimated length: 2 hours, 20 minutes, including 1 intermission Recommended for students in grades 9 through 12. Themes, Issues, & Topics The Civil Rights movement coming of age The Feminist movement The changing political structure of the old South The change in American politics brought about by vocal African Americans Upward mobility of African Americans Student Matinees at 10:00 A.M. on April 8 & 10 Contents Pl;aywright 3 Artistic Director’s Note 4 Director’s Note 5 Designer Notes 6 Maynard Jackson 8 The World in 1973 10 Interactive Civil Rights Timeline 12 Indiana Academic Standards 15 Resources 16 Before Seeing the Play 18 Education Sales Questions, Writing Prompts, Activities 18 Randy Pease • 317-916-4842 Vocabulary 22 [email protected] Works of Art – Kyle Ragsdale 28 Going to the Theatre 29 Pat Bebee • 317-916-4841 [email protected] Outreach Programs Milicent Wright • 317-916-4843 [email protected] INDIANA REPERTORY THEATRE 3 Pearl Cleage • Playwright “The purpose of my writing, often, is to express the point where racism and sexism meet.” Pearl Cleage was born in 1948 in Springfield, Massachusetts, and grew up in Detroit, Michigan. -

The Historymakers: a New Primary Source for Scholars

The HistoryMakers: A New Primary Source for Scholars Julieanna L. Richardson Vernon D. Jarrett Senior Fellow Great Cities Institute College of Urban Planning and Public Affairs University of Illinois at Chicago Great Cities Institute Publication Number: GCP-07-08 A Great Cities Institute Working Paper April 2007 The Great Cities Institute The Great Cities Institute is an interdisciplinary, applied urban research unit within the College of Urban Planning and Public Affairs at the University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC). Its mission is to create, disseminate, and apply interdisciplinary knowledge on urban areas. Faculty from UIC and elsewhere work collaboratively on urban issues through interdisciplinary research, outreach and education projects. About the Author Julieanna Richardson is the Vernon D. Jarrett Senior Fellow at The Great Cities Institute of the University of Illinois at Chicago. She is also founder and Executive Director of The HistoryMakers, an oral history archive founded in 1999. She can be reached at [email protected]. Great Cities Institute Publication Number: GCP-07-08 The views expressed in this report represent those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the Great Cities Institute or the University of Illinois at Chicago. This is a working paper that represents research in progress. Inclusion here does not preclude final preparation for publication elsewhere. Great Cities Institute (MC 107) College of Urban Planning and Public Affairs University of Illinois at Chicago 412 S. Peoria Street, Suite 400 Chicago IL 60607-7067 Phone: 312-996-8700 Fax: 312-996-8933 http://www.uic.edu/cuppa/gci UIC Great Cities Institute The HistoryMakers: A New Primary Source for Scholars Abstract This paper explores the possibilities of increasing the use and accessibility of The HistoryMakers’ video oral history archive. -

CLEAGE, PEARL. Pearl Cleage Papers, 1949-2011

CLEAGE, PEARL. Pearl Cleage papers, 1949-2011 Emory University Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library Atlanta, GA 30322 404-727-6887 [email protected] Collection Stored Off-Site All or portions of this collection are housed off-site. Materials can still be requested but researchers should expect a delay of up to two business days for retrieval. Descriptive Summary Creator: Cleage, Pearl. Title: Pearl Cleage papers, 1949-2011 Call Number: Manuscript Collection No. 1223 Extent: 74.75 linear feet (156 boxes), 12 oversized papers boxes (OP), 4 extra- oversized papers (XOP), 1 oversized bound volume (OBV), AV Masters: 6 linear feet (6 boxes), and 1.41 GB born digital materials (564 files) Abstract: Personal papers of African American novelist and playwright Pearl Cleage including correspondence, manuscript and typescript writings, subject files, professional papers, printed material, photographs, writings by others, and audiovisual material. Language: Materials entirely in English. Administrative Information Restrictions on Access Special restrictions apply: Series 1: Personal journals are closed to researchers until December 2037. Series 2: Due to privacy concerns, some material has been redacted. Series 3: Due to privacy concerns, some material has been redacted. Series 4: Professional papers are closed to researchers until December 2037. Collection stored off-site. Researchers must contact the Rose Library in advance to access this collection. Emory Libraries provides copies of its finding aids for use only in research and private study. Copies supplied may not be copied for others or otherwise distributed without prior consent of the holding repository. Pearl Cleage papers, 1949-2011 Manuscript Collection No. -

Triptych Eyes of One on Another

Saturday, September 28, 2019, 8pm Zellerbach Hall Triptych Eyes of One on Another A Cal Performances Co-commission Produced by ArKtype/omas O. Kriegsmann in cooperation with e Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation Composed by Bryce Dessner Libretto by korde arrington tuttle Featuring words by Essex Hemphill and Patti Smith Directed by Kaneza Schaal Featuring Roomful of Teeth with Alicia Hall Moran and Isaiah Robinson Jennifer H. Newman, associate director/touring Lilleth Glimcher, associate director/development Brad Wells, music director and conductor Martell Ruffin, contributing choreographer and performer Carlos Soto, set and costume design Yuki Nakase, lighting design Simon Harding, video Dylan Goodhue/nomadsound.net, sound design William Knapp, production management Talvin Wilks and Christopher Myers, dramaturgy ArKtype/J.J. El-Far, managing producer William Brittelle, associate music director Kathrine R. Mitchell, lighting supervisor Moe Shahrooz, associate video designer Megan Schwarz Dickert, production stage manager Aren Carpenter, technical director Iyvon Edebiri, company manager Dominic Mekky, session copyist and score manager Gill Graham, consulting producer Carla Parisi/Kid Logic Media, public relations Cal Performances’ 2019 –20 season is sponsored by Wells Fargo. ROOMFUL OF TEETH Estelí Gomez, Martha Cluver, Augusta Caso, Virginia Kelsey, omas McCargar, ann Scoggin, Cameron Beauchamp, Eric Dudley SAN FRANCISCO CONTEMPORARY MUSIC PLAYERS Lisa Oman, executive director ; Eric Dudley, artistic director Susan Freier, violin ; Christina Simpson, viola ; Stephen Harrison, cello ; Alicia Telford, French horn ; Jeff Anderle, clarinet/bass clarinet ; Kate Campbell, piano/harmonium ; Michael Downing and Divesh Karamchandani, percussion ; David Tanenbaum, guitar Music by Bryce Dessner is used with permission of Chester Music Ltd. “e Perfect Moment, For Robert Mapplethorpe” by Essex Hemphill, 1988. -

Biographical Description for the Historymakers® Video Oral History with Pearl Cleage

Biographical Description for The HistoryMakers® Video Oral History with Pearl Cleage PERSON Cleage, Pearl Alternative Names: Pearl Cleage; Life Dates: December 7, 1948- Place of Birth: Springfield, Massachusetts, USA Residence: Atlanta, GA Occupations: Essayist; Fiction Writer; Playwright Biographical Note Writer, playwright, poet, essayist, and journalist Pearl Michelle Cleage was born on December 7, 1948 in Springfield, Massachusetts. Cleage is the youngest daughter of Doris Graham and Albert B. Cleage Jr., the founder of the Shrine of the Black Madonna. After graduating from the Detroit public schools in 1966, Cleage enrolled at Howard University, where she studied playwriting. In 1969, she moved to Atlanta and enrolled at Spelman College, married Michael Lomax and became a mother. She graduated from Spelman College in 1971 with a bachelor’s degree in drama. and became a mother. She graduated from Spelman College in 1971 with a bachelor’s degree in drama. Cleage has become accomplished in all aspects of her career. As a writer, she has written three novels: What Looks Like Crazy on an Ordinary Day (Avon Books, 1997), which was an Oprah’s Book club selection, a New York Times bestseller, and a BCALA Literary Award Winner, I Wish I Had a Red Dress (Morrow/Avon, 2001), and Some Things I Never Thought I’d Do, which was published in 2003. As an essayist, many of her essays and articles have appeared in magazines such as Essence, Ms., Vibe, Rap Pages, and many other publications. Examples of these essays include Mad at Miles and Good Brother Blues. Cleage has written over a dozen plays, some of which include Flyin’ West, Bourbon at the Border, and Blues for an Alabama Sky, which returned to Atlanta as part of the 1996 Cultural Olympiad in conjunction with the 1996 Olympic Games. -

Now That's a Good Girl: Discourses of African American Women, HIV/AIDS, and Respectability

Now That’s a Good Girl: Discourses of African American Women, HIV/AIDS, and Respectability A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Ayana K. Weekley IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Jigna Desai, Adviser August 2010 © Ayana K. Weekley 2010 Acknowledgements There are many, many people and institutions that played a role in my completion of this dissertation. First, I want to say thank you to my adviser, Jigna Desai. Jigna has guided me intellectually since 2004 and has always both challenged, encouraged me and treated me with respect. My success in scholarship and teaching is largely due to her. Jigna, I am lucky to have been held to your academic standards. Second, is my co-adviser, Gwendolyn Pough. Gwen made sure I came to the Feminist Studies Program and immediately assumed the role of adviser when I began. While Gwen moved to another institution, she remained on my committee and worked closely with me throughout my dissertation process. Gwen, without your early support in this process I surely would not have made it over all the hurdles. Various programs and institutions provided the financial support that made it possible for me to have time to research and write. They include the McNair Undergraduate Research Opportunity Programs at Truman State University and the University of New Hampshire, Durham; the Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Department at the University of Minnesota; MacArthur Scholars Fellowship, MacArthur Interdisciplinary Program on Global Change, Sustainability and Justice, University of Minnesota; the HECUA Philanthropy and Human Rights Fellowship, the Woodrow Wilson Women's Studies Dissertation Fellowship; The Frederick Douglass Institute for African and African American Studies Pre-Doctoral Fellowship at the University of Rochester; and the Presidential Fellowship at the State University of New York, Brockport. -

Journal of Haitian Studies, Volume 19, Number 1, Spring 2013, Pp

7KH/HJDF\RI$VVRWWR6DLQW7UDFLQJ7UDQVQDWLRQDO +LVWRU\IURPWKH*D\+DLWLDQ'LDVSRUD Erin Durban-Albrecht Journal of Haitian Studies, Volume 19, Number 1, Spring 2013, pp. 235-256 (Article) 3XEOLVKHGE\&HQWHUIRU%ODFN6WXGLHV8QLYHUVLW\RI&DOLIRUQLD 6DQWD%DUEDUD DOI: 10.1353/jhs.2013.0013 For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/jhs/summary/v019/19.1.durban-albrecht.html Access provided by Illinois State University (29 Mar 2016 16:46 GMT) The Journal of Haitian Studies, Volume 19 No. 1 © 2013 THE LEGACY OF ASSOTTO SAINT: TRACING TRANSNATIONAL HISTORY FROM THE GAY HAITIAN DIASPORA Erin Durban-Albrecht University of Arizona INTRODUCTION This essay uses Michel-Rolph Trouillot’s notion of power and the production of history as a starting point to explore the ways that Assotto Saint (1957-1994), a gay Haitian American who was once a well-known player in the Black gay and AIDS activist cultural movements in the United States, is remembered and written about in contemporary venues.1 I argue that the politics of remembrance pertaining to Saint’s cultural work and activism has significant consequences for our understanding of late twentieth century social and cultural movements in the United States as well as gay Haitian history. I explore the fact that Saint’s work has fallen out of popularity since his death in 1994, except in limited identitarian, mostly literary venues. The silences surrounding his work that I describe in this essay are peculiar considering that Saint not only had important social connections with artists who are well-known today, but also, unlike artists with less access to financial resources, he left behind a huge archive of materials housed in the Black Gay and Lesbian Collections at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture as well as a rich and prolific corpus of published work. -

Black/Out Is a Magazine By, for and —Ann Chapman; P

B LACK/OUT The Magazine of the National Coalition of Black Lesbians and Gays Volume 1 Number 1 Summer 1986 $3 Simon Nkodi: On Trial for Treason by James Charles Roberts page 6 Working for Liberation and Having a Damn Good Time! by Barbara Smith page 13 Poetry: Julie Blackwomon Dan Garrett Stephen F. Langley Sonia Sanchez page 18 v-lisi: $ i^K" CONTENTS BLACK/OUT NEWS Publisher NCBLG National Conference on AIDS Among Blacks National Coalition of Black Lesbians and Gays, Inc., a non-profit organization that provides advocacy on by Craig G. Harris 4 issues affecting Black Lesbians and Gays. Simon Nkodi: On Trial for Treason by James Charles Roberts 6 Board of Directors Timothy Lee: Murder or Suicide? Michelle Parkerson, Co-chair by James Charles Roberts Louis Hughes, Jr., Co-chair 6 Gwendolyn Rogers, Secretary Clifton A. Roberson, Treasurer Joseph F. Beam NEWS BRIEFS Angela Bowen Gays, Lesbians and bisexuals of color convene; Hemphill receives Audre Lorde NEA grant; Bowen at NOW march; Parkerson, Hemphill and Jones Marietta G. Mason receive Residency for New Works grant ••. 5 Luvenia Pinson Betty Powell Barbara Smith Lawrence Washington FEATURES Charles Williams The NCBLG Family Gathers: A Conference Report Dan Weddo by Craig G. Harris 10 Executive Director Working for Liberation and Having a Damn Good Time! by Barbara Smith 13 Gil Gerald Two Views on The Color Purple Publications Committee It's Not for Me to Say by Angela Bowen 15 Editor All in the Family by R. Harris 15 Joseph F. Beam Associate Editors Angela Bowen DEPARTMENTS Barbara Smith OUT/LOOK "Black Pride and Solidarity: The New Movement Dan Weddo of Black Lesbians and Gays" by Gil Gerald 3 News Correspondents James Charles Roberts, Philadelphia OUT/POSTS News from the Chapters 7 Colin Robinson, New York OUT/LET "Caring for Each Other" by Joseph Beam 9 Typesetting/Design Essex Hemphill COMING OUT by Angela Bowen 12 Cover Art POETRY Sonia Sanchez, Dan Garrett, Stephen F. -

Love, Liberation, and the Rise of Black Lesbian and Gay Cultural Politics in Late Twentieth Century America

“Out of This Confusion I Bring My Heart” Love, Liberation, and the Rise of Black Lesbian and Gay Cultural Politics in Late Twentieth Century America by David B. Green Jr. A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (American Culture) in The University of Michigan 2015 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Maria E. Cotera, Chair Professor Frieda Ekottto Assistant Professor Brandi S. Hughes Assistant Professor Victor R. Mendoza When you love as we did you will know There is no life but this And history will not be kind Melvin Dixon (I)Eye dedicate this work to My Brother O.B. Green Who was taken too soon from this earth ii Acknowledgements I believe…no—wait—I remember. Yes. I remember the exact moment when I received a call from Jesse Huffnung-Garskof. Jesse called to inform me that I had been admitted into the Program in American Culture here at the University of Michigan. I was in Der Rathskeller, the main lunch drag at the University of Wisconsin’s student union. In the middle of grabbing one of their delicious cheeseburgers, I struggled to retrieve my cell phone. “Hello?...hello yes, this is David.” Moments later I was screaming. “Really?!” Yes, I was admitted into a doctoral program at the University of Michigan— one of two programs that accepted me. I knew nothing about this university. To tell the truth, I had never heard of the University of Michigan. Seriously. When I was completing my Master’s thesis and applying to doctoral programs, a colleague, Eric Darnell Pritchard—who had completed his Master’s degree in African American Studies and Doctoral degree in English Rhetoric at Wisconsin and now works as an Assistant Professor at the University of Texas at Austin—encouraged me to apply to Michigan. -

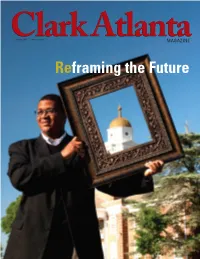

Reframing the Future

Summer /2011 www.cau.edu MAGAZINE Reframing the Future CLARK ATLANTA UNIVERSITY SUMMER 2011 1 PROVOST’s LETTER MAGAZINE WWW.CAU.EDU “A Change is Gonna Come….” PRESIDENT FEATURES Carlton E. Brown A popular song from the 1960s promises, “A Change is Gonna Come.” Those of us who recall its debut can DIRECTOR OF STRATEGIC The Game Changers 13 attest to the fact that the song’s promise is not an empty one: change is a constant. COMMUNICATIONS Each having changed the game in his or her respective field, these six CAU As provost of this great university, I am afforded a tremendous vantage point on how faculty and staff are Donna L. Brock alumni share their wisdom with the emerging generation of leaders. enthusiastically embracing and shaping tomorrow. Of course, many university administrators will boast the EDITOR Education - Carlton E. Brown 14 same; however, few have the opportunity to actively “rethink” a university and the manner in which it antici- Joyce Jones Business - Kimberly Hairston 15 pates and prepares students for the future. Our strategic plan NEWS EDITOR Health - Dr. James K. Bennett 16 creates the perfect framework for this undertaking, and I Jennifer Jiles count this as one of Clark Atlanta’s most fortuitous blessings. Politics - Congressman Hank Johnson 17 CONTRIBUTORS Religion - Rev. Dr. Mark K. Tyler 18 While a doctoral student here 30 years ago, my class- Paul M. Brown, Ph.D., Martha mates and I wrestled with the issues of the day, and today Buckman, Jacqueline Gayle, Dana Arts - Pearl Cleage 19 as contributors in diverse fields of endeavor, we continue to Harvey, David Lindsay, Frank McCoy, Matthew Scott Commencement 2011 20 apply what we learned in addressing concerns that impact our communities, locally, nationally and globally. -

ITL Frontmatter

thein A BLACK GAY ANTHOLOGY thein A BLACK GAY ANTHOLOGY edited by Joseph Beam New Introduction by James Earl Hardy WASHINGTON, DC www.redbonepress.com In the Life: A Black Gay Anthology Copyright © 1986 by Joseph Beam; © 2008 by Estate of Joseph Beam New Introduction, “And We Continue to Go the Way Our Blood Beats...” copyright © 2008 by James Earl Hardy Individual selections copyright © by their respective author(s) Published by: RedBone Press P.O. Box 15571 Washington, DC 20003 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the publisher, except in the case of reviews. 08 09 10 11 12 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Second edition Cover design by Eunice Corbin Logo design by Mignon Goode Joseph Beam cover photo copyright © 1985 by Sharon Farmer Permissions acknowledgments appear on pp. 219. Artwork on p. 1 by Deryl Mackie; photograph on p. 23 by Joseph Beam; artwork on p. 45 by Don Reid; artwork on p. 69 by Vega; artwork on p. 115 by Tawa; photograph on p. 173 by Joseph Beam. Printed in the United States of America ISBN-13: 978-0-9786251-2-2 ISBN-10: 0-9786251-2-9 www.redbonepress.com for my parents, Dorothy and Sun F. Beam for loving for Kenyatta Ombaka Baki for believing for Addie and Charles for our future Contents And We Continue to Go the Way Our Blood Beats..., by James Earl Hardy / ix Acknowledgments / xv Introduction / xix Coming of Age, Brad Johnson / xxv Stepping Out The Boy with Beer, Melvin Dixon / 2 With My Head Held Up High, Gilberto Gerald / 14 Cut Off from Among Their People On Not Being White, Reginald Shepherd / 24 Beautiful Blackman, Blackberri / 35 Don’t Turn Your Back on Me, Stephan Lee Dais / 37 Cut Off from Among Their People, Craig G.